“Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”1

The update reflects the most current understanding of dry-eye disease as a disruption in homeostasis and emphasizes the importance of hyperosmolarity in dry-eye tears and the role of inflammation in DED. Inflammatory mediators are frequent therapeutic targets. As things stand, Restasis and Xiidra (Allergan and Shire, respectively) are the only prescription eye drops approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of dry-eye disease. Both medications are thought to inhibit T cells by different mechanisms of action. The heterogeneous nature of dry-eye disease is one of the things confounding new drug development: Drug makers have multiple potential molecular and tissue targets to consider and DED is notorious for a lack of overlap between signs and symptoms.2 With an estimated global prevalence ranging from 5 to 50 percent3 and the potential for corneal surface damage and diminished quality of life absent good treatment, DED’s therapeutic pipeline is unlikely to run dry anytime soon.

Four dry-eye treatments at various stages follow: a freshly FDA-approved medical device; a drug in the middle of the investigational stage; a patented topical solution/gel formulation; and a protein-fragment-based drop beginning a human trial.

TrueTear

Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the spring of 2017, Allergan’s TrueTear Intranasal Tear Neurostimulator device relies on an old idea—nerve stimulation—to address the problem of dry eye. Oculeve, the startup that invented the device before being purchased by Allergan, based TrueTear on technology used in TENS units and for the treatment of movement disorders. The TrueTear stimulates the trigeminal nerve and, in turn, the seventh cranial nerve with small electrical pulses that ultimately trigger the lacrimal gland to produce tears.

To reach the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve, this small handheld device has two prongs covered in disposable hydrogel tips that go up the patient’s nostrils. Patients can choose from five levels to control the intensity of electrical stimulation. According to patient information for the TrueTear,4 patients should

|

| The TrueTear is an intranasal device that uses neurostimulation. |

Supportive data released by Allergan4 consist of two studies: OCUN-009, a look at one-day correct use of the device versus one-day sham control treatments, and OCUN-010, a six-month trial comparing tear production at six months to baseline. Forty-eight dry-eye patients at two sites underwent three applications of neurostimulation in OCUN-009: correctly applied intranasal stimulation treatment with an active TrueTear; intranasal application of an inactive TrueTear; or extranasal (incorrect) application of an active TrueTear. The average Schirmer’s score for the treatment group was 25 mm during treatment, versus 9 mm for both sham groups. OCUN-010 was an interventional open-label study looking at tear production in 97 dry-eye patients at treatment days one, seven, 30, 90 and 180. Patients were told to use the TrueTear anywhere from two to 10 times per day for a maximum of three minutes per session. At each follow-up visit, Schirmer’s testing without stimulation was compared to scores with stimulation; tear production was consistently significantly greater with active TrueTear stimulation than without. The effect appeared to decrease from the first-day results but then plateaued over time (still remaining higher than without stimulation). The average differences in Schirmer’s scores (with stimulation versus without) were 18 mm on day one, 13.1 mm at seven days, 8.1 mm at 30 days, 8.3 mm at 90 days and 9.4 mm at 180 days. In both studies, adverse events were minor and included nasal complaints such as irritation.

“Crazy,” is how John Berhdahl, MD, of Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, S.D., sums up his first impression of the TrueTear upon getting the chance to try it out a couple of years ago. “But I love outside-the-box ideas, and as I thought about it more deeply, it made sense,” he says. “We know that reflex tearing can occur when you stimulate nerves, and it’s not so different from other electrotherapies that we use to stimulate nerves in other parts of the body. I believed that it would be safe, so I thought, ‘Let’s try it. Let’s see if this crazy idea turns out to be legit,’” he recalls.

So far, Dr. Berdahl reports that patients are having “a very good response” to the TrueTear since it has become generally available. “I like that we’re using concepts outside of ophthalmology like electrostimulation and applying them to ophthalmology to see if we can control the pathophysiology of the eye: I think that’s great,” he says. He thinks that the high degree of control over treatment that the device affords patients is one factor in its success to date. “One of the things that’s really nice about it is that we allow them to try it in the office so that they can experience the increased tearing,” he notes. “Then they can try it for a month, and if it’s not working for them, it can be returned. Those two steps allow people to climb the learning curve in a noncommittal way.”

Dr. Berdahl also values the safety and flexibility of the TrueTear, since it fits well into comprehensive treatment plans that include other modalities. “I believe in treating severe dry eye by hitting it really, really hard to get it under control and then backing off the things that you no longer need, or that the patient likes the least,” he says. Using the TrueTear is part of that treatment philosophy for dozens of patients in his practice.

Surgeons say that the base price of the TrueTear is $750 and a month’s supply of disposable tips costs $250, although Allergan does offer some rebates to help defray costs.

In addition to stimulating the lacrimal gland in aqueous-deficient dry eye, Dr. Berdahl says that there is evidence that using TrueTear improves the tear film in dry eye as well. “They have done some work to show that it improves meibum secretion, so it would improve tear-film quality,” he says. A small study5 suggests that use of the neurostimulator can promote degranulation of conjunctival goblet cells in both dry and healthy control eyes.

CyclASol

Since its launch in 2003, Restasis (0.05% cyclosporine A emulsion), has been a dry-eye treatment mainstay, thought to inhibit the action of inflammatory T-cell mediators. Cyclosporine eye drops, however, present the same roadblocks to efficacy and compliance as other topical drops: Many patients have difficulty getting them into the eye without blinking as soon as they reach the cornea, which results in spillover and drainage into the lacrimal system before the drug can provide much therapeutic benefit.

Novaliq GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany) has combined cyclosporine A with its Eyesol drug-delivery platform, which is made up of semifluorinated alkanes, in a bid to create a more bioavailable and user-friendly alternative to aqueous drops.

Semifluorinated alkanes aren’t new to ophthalmology because they possess characteristics that make them suitable tamponades in vitreoretinal surgery, including good solubility in silicone oils, perfluorocarbon and hydrofluorocarbon liquids; a refractive index of 1.3; and a specific gravity of 1.35 g/mL.6 Those attributes also make semifluorinated alkanes good for mixing with cyclosporine A—a drug with poor water solubility—to make a slick, clear, preservative-free solution with low surface tension that spreads rapidly over the ocular surface.

One drop of a 0.05% aqueous emulsion has a volume of 40 to 50 μL: a drop of that size triggers reflexive blinking in many patients when it contacts the eye. To create a cyclosporine A drop that will more successfully reside on the cornea, Novaliq has developed CyclASol, a preservative-free cyclosporine A solution with Eyesol. Novaliq says that a drop of CyclASol is only about 10 μL in volume, so it doesn’t trigger a blink reflex and accompanying spillover in the eye, and its low surface tension allows the drop to spread over the cornea more quickly and evenly than aqueous eye drops. Alternate dry-eye treatments include gels and ointments, but these are often limited to nighttime use because they blur and distort vision, even though they reside on the cornea better than aqueous drops. The company claims that CyclASol’s refractive index is very close to that of the crystalline lens, so it will not blur or distort vision.

A Phase II study (Trial Identifier: NCT02617667) comparing two dose levels of CyclASol (0.05% and 0.1%) solution with cyclosporine A 0.05% emulsion and a placebo followed 207 randomized patients with moderate-to-severe dry-eye disease for four months. Novaliq released topline data from this study in early 2017.7 Although patients in all treatment arms showed reduced corneal fluorescein staining, patients enrolled in both CyclASol groups showed significantly more disease-sign improvement than patients in the vehicle (placebo) group. Novaliq says that its data also demonstrated that CyclASol patients began showing reduced corneal and conjuctival staining as early as 14 days into treatment. It reports that the drops were well tolerated with no serious adverse events. Novaliq added that improvement was most marked in the central area of the cornea and noted that area’s importance to good visual functioning.

Upon release of the topline data, a company press release7 quoted Claus Cursiefen, MD, PhD, FEBO, professor and chair of the ophthalmology department at University of Cologne, Germany, and member of Novaliq’s scientific advisory board, on the therapeutic benefits of CyclASol: “Consistent improvements in several measures of ocular inflammation of dry-eye disease, particularly the improvement in central corneal staining, is a very important feature of the formulation because it positively influences visual function. This, combined with the early onset of action and an excellent tolerability profile, represents a highly relevant improvement over currently available therapies.”

Klarity

In the spring of 2017, Imprimis Pharmaceuticals (San Diego) announced that it had purchased the exclusive worldwide rights to Klarity, a patented topical ophthalmic solution created by Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, to protect and heal the ocular surface in moderate-to-severe DED. Klarity is also intended for dry eye and corneal irregularities arising from intraocular surgery or contact lens wear.

The preservative-free Klarity solution contains chondroitin sulfate, thought to have protective and healing effects on the corneal epithelium,8 and established as safe for intraocular use in viscosurgery. It also contains dextran and glycerol. Imprimis says that the solution can be formulated to vary in viscosity, making it suitable as a topical drop, a gel or even a dispersive OVD.

The company plans to make Klarity part of its emerging dry-eye program. According to the Imprimis website, another upcoming addition is the compounding of autologous serum tears at the company’s 503A PCAB-accredited pharmacies.

Lacripep

Lacripep (TearSolutions, Inc.) is a synthetic protein fragment incubated in the Laurie Cell Biology Laboratory at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Its inventor, Gordon W. Laurie, PhD, professor of cell biology, biomedical engineering and ophthalmology at UVA and co-founder and CSO of TearSolutions, and colleagues say that Lacripep is potentially the first therapeutic agent capable of improving dry-eye disease regardless of etiology.

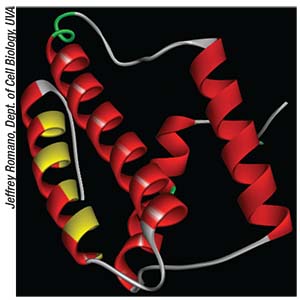

“Lacripep is a synthetically generated 19-amino-acid fragment of lacritin,” Dr. Laurie explains. “Lacritin is a naturally occurring protein in tears, first identified in 2001 by the Laurie Cell Biology Lab out of an unbiased discovery screen for factors that regulate basal tearing.” He notes that Lacripep-like lacritin fragments occur naturally in tears secreted by healthy eyes—and that they are deficient (as is lacritin) in dry-eye tears. “Lacripep and lacritin have been studied in several dry-eye animal and human cellculture models, and have been found to restore ocular surface health by: promoting tear protein release and tearing, even under conditions of inflammation; transiently stimulating a cellular lysosomal pathway known as autophagy to rid cells of damaged proteins and organelles that accumulate under conditions of stress; and restoring mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. In unpublished data, both also appear to stimulate and benefit sensory nerves at the ocular surface that in dry eye are disrupted and diminished,” he says.

This neural stimulation may bring relief for both aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry-eye patients. “By apparently targeting corneal sensory nerves that in turn regulate all glandular and secretory elements of the ocular surface, Lacripep is expected to benefit both evaporative and aqueous-deficient dry eye,” Dr. Laurie explains.

With support from the National Eye Institute,

|

| A molecular model of lacritin, a protein that is selectively deficient in dry-eye tears. Lacripep is a synthetic lacritin fragment. |

“A shout-out to the National Eye Institute for their many years of support, without which this discovery would not have been possible,” says Dr. Laurie. “We also wish to acknowledge the Lacritin Consortium of labs in the U.S. and outside, who have contributed fundamentally to our understanding of Lacritin,” he says.

Dr. Laurie, Marc G. Odrich, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at University of Virginia and medical director of TearSolutions, Inc., and colleagues have recently begun an attempt to transition from the laboratory to the marketplace with a double-masked, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II study of topical Lacripep in more than 200 patients with Sjögren’s-associated dry-eye disease at 27 U.S. sites (Trial Identifier: NCT03226444). Enrolled patients receive one of two concentrations of Lacripep eye drops or a placebo three times a day for four weeks. Improvement in fluorescein corneal staining is the primary endpoint.

Dr. Odrich says that they selected Sjögren’s patients for the first study because primary dry eye associated with the disorder “is the most homogenous form of dry-eye disease, with diagnosis aided by blood tests and salivary gland biopsy.” He adds, “Second, lacritin deficiency in Sjögren’s syndrome correlates with reduced corneal nerve fiber density and length, tear insufficiency, increased ocular staining and reduced corneal sensitivity. Third, in two different mouse models of Sjögren’s syndrome, lacritin promoted rapid resolution of corneal staining and/or tearing. Fourth, Sjögren’s syndrome patients are highly motivated.”

Dr. Odrich estimates that data will become available in the first half of 2018. Should Lacripep garner FDA approval in the future, he believes that patients could titrate the number of daily doses down from three once their condition stabilizes. “There appears to be a lasting effect with repeated dosing,” Dr. Odrich says of his team’s studies in rabbits that were dosed three times daily for two weeks. “Basal tearing steadily increased and remained elevated one week after washout.The molecular basis is under study. At least two different mechanisms are likely involved,” he says.

The dry-eye pipeline is tricky for a variety of reasons: the heterogeneity of the target disease; the lack of overlap between signs and symptoms; and the costly path to FDA approval, to name a few. As the most prevalent ocular surface disease globally, however, DED will never be without therapeutic contenders.

“Dry eye is a disease that has real unmet needs because we can’t get everybody better right now,” Dr. Berdahl observes. “So I’m excited about all of it, but it remains to be seen which things will be the most clinically useful.” REVIEW

Dr. Berdahl is a consultant to Allergan. As mentioned in the article, Drs. Laurie and Odrich are the CSO and medical director, respectively, of TearSolutions, Inc.

1. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf 2017;15;3:276-83.

2. Novack GD. Why aren’t there more pharmacotherapies for dry eye? Ocul Surf 2014;12;3:227-29.

3. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf 2017;15;3:334-65.

4. Allergan. Patient Guide to the TrueTear intranasal tear neurostimulator. https://allergan-web-cdn-prod.azureedge.net/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/labeling/ifu_truetear_patient.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2017.

5. Gumus K, Schuetzle KL, Pflugfelder SC. Randomized controlled crossover trial comparing the impact of sham or intranasal tear neurostimulation on conjunctival goblet cell degranulation. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;177:159-68.

6. Alovisi C, Panico C, de Sanctis U, Eandi CM. Vitreous substitutes: Old and new materials in vitreoretinal surgery. J Ophthalmol 2017;2017:3172138. doi: 10.1155/2017/3172138. E-pub ahead of print.

7. Novaliq, “Novaliq announces positive topline results of Phase 2 clinical trial evaluating CyclASol in adults with moderate to severe dry eye disease,” (2017). Available at: http://bit.ly/CyclASol. Accessed August 28, 2017.

8. Sandri G, Bonferoni MC, Rossi S, Delfino A, Riva F, et al. Platelet lysate and chondroitin sulfate loaded contact lenses to heal corneal lesions. Int J Pharm 2016;25;509(1-2):188-96.