Trabeculectomy remains the gold standard for long-term pressure control in glaucoma patients. In recent years, its potential safety has been enhanced with variations such as the "safe trabeculectomy" technique advocated by Peng T. Khaw, MD, that creates broader blebs with a theoretically decreased risk of bleb leak over time. Nevertheless, the search continues for an ideal replacement.

One of the obvious contenders is glaucoma drainage devices—a well-established alternative for pressure reduction. (Anthony Molteno, MD, first described his device in the 1970s.) This option has received more attention since the Tube vs. Trabeculectomy study found that tube shunts and trabeculectomy resulted in basically equivalent pressures at one year post-op, but with significantly fewer complications and a lower failure rate in the tube group.1,2

Given this new level of interest, I believe it's important to investigate the comparative benefits and drawback of both options—including cost considerations.

Comparing Costs

For many years I worked with my late husband, J. William Doyle, MD, PhD, at the

Veteran's Administration hospital in

trabeculectomy.

About a year later, when discussing our study, we turned our attention to the number of complications and postoperative visits in our trabeculectomy group. There were many more follow-up visits for the trabeculectomy patients because we often saw the trabeculectomy patients every day or every other day during the immediate postop period; tube shunt patients only had to be seen every week or two.

I began to wonder: What are the cost ramifications of this difference for a practice? For the surgeon? The staff? The patient? As everyone in our field knows, glaucoma care in the

For this new study, we looked at 71 patients in the trabeculectomy group and 42 in the glaucoma drainage device group, with help from residents Michael Connor and Rob Knape. We found that the initial surgery costs were remarkably similar. You might expect glaucoma drainage devices to be costlier because of the expense of the implant and the pericardium patch graft, but with novice (i.e., slower) surgeons, taking into account the OR time, anesthesia, staff for the case and so forth, we found that there was no statistically significant difference in actual surgery cost. (See table, below.)

However, other cost issues were significantly different in the postop period. For example, we found differences in the number of average follow-up visits per patient—an average of eight follow-ups per patient in the tube group vs. 15 in the trabeculectomy group. We approximated the cost of the different elements of these visits in consultation with our colleagues at the hospital and came up with a cost of about $100 per visit, resulting in a total extra cost of about $700 per patient for the extra visits in the trabeculectomy group.

Then there was the cost of managing complications. Twenty-five percent of our novice surgeons' trabeculectomies required anterior chamber reformations with viscoelastic; very few patients with tube shunts needed this, and those that did usually only required one. We also found that more bandage contact lenses were used in the trabeculectomy group, and these patients required more minor repairs such as placing sutures, which tube shunts seldom required.

About the only thing that was more expensive in the tube group was the cost of post-surgery glaucoma medications, a direct consequence of our preference for the Baerveldt drainage device. (In my experience, the Baerveldt has always provided excellent long-term pressure control.) Because the Baerveldt is a non-valved device, it doesn't provide a great deal of pressure control until the vicryl tube ligation suture dissolves about six weeks postop. So during the early postop period, we frequently use glaucoma meds to control the pressure until the ligature dissolves. (Using an Ahmed valve might have eliminated this extra cost.) With that one exception, there were more expenses in the trabeculectomy group. The final total cost difference was statistically significant—a median cost of $11,321 per patient in the trabeculectomy group vs. $7,353 in the tube group.

It's true that most trabeculectomies are done as outpatient procedures, which are less expensive than inpatient care. Our study was set at the veterans' hospital where I had the luxury of admitting patients when I felt it was appropriate. Many of our patients drove for hours to see us, so we admitted almost every trabeculectomy patient; we were concerned that they'd need more intensive postop care. In contrast, we frequently let our tube shunt patients leave after a day.

How does the inpatient vs. outpatient factor affect the cost results in our study? If we had not admitted these patients to the hospital, many of the hospital costs would have been replaced by the need for more postop clinic visits. For that reason, I think the cost ratio would be very similar to what we found, with the trabeculectomies ending up being more expensive; the total costs for both procedures would simply be lower.

These numbers raise an obvious question. If you have strong data like that from the Tube vs. Trabeculectomy trial stating that you'll achieve similar outcomes regardless of whether you use trabeculectomy or a glaucoma drainage device, and other data (admittedly from a far less impressively designed retrospective study) suggests a significant difference in cost, why wouldn't you consider implanting tube shunts more often? This would especially seem a worthy consideration in the case of novice surgeons who have far less experience performing trabeculectomies.

What About Experienced Surgeons?

Because our study data was based on patients treated by novice surgeons, it's worth considering whether the cost difference we found between trabeculectomy and glaucoma drainage devices would exist if the data came from surgeons who were more experienced at performing trabeculectomy. This might make a difference because trabeculectomy is something of an art. The thickness of the flap must be exactly right; you have to put in just the right number of releasable sutures and know when to release them. And you have to know whether to leave the eye filled with viscoelastic on the table. For these and other reasons, it's reasonable to expect that a trabeculectomy performed by a highly experienced surgeon would result in fewer postop complications.

As an experienced trabeculectomy surgeon, I suspect I have lower costs than my residents because I don't see a lot of flat chambers or choroidal effusions. However, I may see a patient six times in the first two weeks just to pull sutures and titrate the outflow. With my glaucoma drainage devices, if the surgery goes well, I see the patient on postop days one and eight and then may give the patient two weeks off. So, I believe even experienced trabeculectomy surgeons will find an asymmetry of cost, though perhaps not as marked a difference as for a novice surgeon who hasn't perfected the art of trabeculectomy and deals with more postoperative issues.

One of the advantages of tube shunts, in our experience, is that a surgeon with good hands seems to require less time to acquire competence at implanting them—at least the Baerveldt, which we're most familiar with—to consistently achieve excellent outcomes. Implanting glaucoma drainage devices is a more standardized procedure than trabeculectomy. You put the plate into proper position and suture it on; you insert the tube into the proper place in the anterior chamber; then you put the patch on the eye and close the conjunctiva. (It is possible that a new option such as the ExPress minishunt will allow a certain degree of standardization of trabeculectomy, making it possible to achieve consistently excellent outcomes with less experience.)

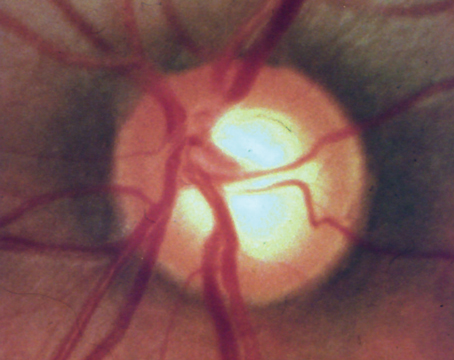

The other major issue that factors into this comparison is the possibility of long-term complications or gradual loss of efficacy with each alternative. Trabeculectomies that are well done, with a nice broad-based bleb that's not particularly prone to leaks or other issues, may turn out to be less problematic in the long run because tube shunts can have issues with corneal decompensation or tube exposure. Long-term data is not conclusive so far, but it's certainly conceivable that a surgeon who is a master of trabeculectomy might find that he has fewer long-term complications with a trabeculectomy. For now, the jury is out.

Should We Switch?

Although this apparent cost difference suggests that glaucoma drainage devices may have a practical advantage over trabeculectomies in the short term, it's not clear whether that means that glaucoma surgeons should definitely shift to implanting more tube shunts, especially as a primary option. In part this is because of uncertainty about the consequences over the long term. And of course, some patients need to achieve very low pressures; trabeculectomies can easily produce pressures in the 8 or 9 mmHg range, while tube shunts generally don't.

On the other hand, for a patient who doesn't have end-stage glaucoma or require a very low pressure, I see the comparative outcome data and cost issues as a valid argument for considering more frequent use of glaucoma drainage devices, including as a primary option. This would especially make sense in patients who don't exhibit severe cupping but have elevated pressures that would be meaningfully reduced at 15 or 16 mmHg, and for older patients for whom long-term issues such as corneal decompensation are less of a concern because the tube won't be in the eye for 50 years. There are also the practical considerations that impact some patients, such as having to drive long distances more often to allow you to manage a trabeculectomy.

In the immediate future, we'll be conducting a retrospective review looking at cornea health in eyes that have had glaucoma drainage devices for 10, 15 or 20 years. In the meantime, I hope surgeons will give glaucoma drainage devices a second look. When I began practicing 15 years ago, tube shunts were the procedure of last choice. Now, given the data from the Tube vs. Trabeculectomy study (which just published three-year outcome data3) and data such as ours suggesting that shunts are associated with fewer short-term postoperative visits, complications and costs, it may be a good time to consider re-evaluating the place glaucoma drainage devices hold in our armamentarium.

Dr. Smith is an associate professor of ophthalmology, co-director of the glaucoma service and co-director of the clinical research center at the

1. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, et al. Treatment outcomes in the tube versus trabeculectomy study after one year of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:1:9-22.

2. Gedde SJ, Herndon LW, et al. Surgical complications in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study during the first year of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:1:23-31.

3. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, et al. Three-year follow-up of the tube versus trabeculectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:5:670-84.