Anti-VEGF injections have revolutionized the treatment of neovascular AMD and diabetic eye disease. Prior to their FDA approval—and in the case of bevacizumab, off-label use—panretinal photocoagulation was the standard of care for diabetic retinopathy. Laser treatment, however, has drawbacks, including loss of peripheral vision and night vision over a course of repeated treatments. Furthermore, although successful laser treatment helps prevent significant vision loss, it may not yield improved visual acuity to the same degree that anti-VEGF therapy can.1 Here, retina specialists explain why retinal laser treatments are still vital for managing PDR, even as the hunt for less burdensome, more effective therapies continues.

Choosing One or Both

“I think it’s best handled as a conversation between physician and patient,” says Michael W. Stewart, MD, professor and chair of ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic Florida in Jacksonville, in reference to the task of helping PDR patients choose whether to try anti-VEGF, laser or a combination of both modalities. “You can start by saying, ‘Here are two choices, and here are the pluses and minuses of both. Given your health and stability, what would you prefer to do?’ By and large, Protocol S from the DRCR.net [Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network] demonstrated that visual acuity is about the same with both,” he says.

DRCR.net Protocol S compared visual-acuity outcomes in high-risk PDR patients who received ranibizumab injections and laser treatment.2 Patients were randomly assigned to PRP or to six intravitreal ranibizumab injections, administered every four weeks, and then PRN at follow-up. The study showed noninferiority of visual outcomes with ranibizumab therapy in comparison to PRP. “The visual fields are generally better and fuller in patients who receive anti-VEGF therapy, so those patients have better peripheral vision. But overall, VA-wise, outcomes are about the same,” says Dr. Stewart.

The patients who got ranibizumab in Protocol S, however, showed less progression of their PDR than did those who underwent PRP, and more regression of central macular thickness. They also didn’t require vitrectomy as often as the patients treated with laser.

A prospective, interventional case series was conducted in 17 patients (20 eyes) with high-risk PDR, who were treated with intravitreal bevacizumab (2.5 mg) followed by PRP when the peripheral vitreous became clear, or two weeks after injection.3 Although this was a small study (20 eyes of 17 patients) with a mean follow-up of 7.5 months, the Snellen visual-acuity testing and fluorescein angiography suggested that combined intravitreal bevacizumab and PRP was an effective treatment option.

At 52 weeks, the Clinical Efficacy of Intravitreal Aflibercept Versus Panretinal Photocoagulation for Best Corrected Visual Acuity in Patients with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (CLARITY) study demonstrated that patients treated with intravitreal aflibercept had better outcomes than patients who received PRP at one year.4

What Does it All Mean?

What do such findings suggest for the future of ophthalmic laser treatments for PDR? “I think it’s patient-dependent, but I personally think the fallback is always laser,” says Dr. Stewart. “The physician and the patient would need to reach an agreement in any individual case. So I think they can agree in certain cases that anti-VEGF would be a better choice, after taking into account concerns such as treatment burden, cost and the possibility of noncompliance.”

Jason Hsu, MD, co-director of retina research at Wills Eye Hospital, associate professor of clinical ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and in practice at Mid Atlantic Retina in the Philadelphia area, is in agreement about the continuing importance of lasers—in no small part because noncompliance is a risk regardless of which therapy ophthalmologists and patients choose. “PRP is still an essential therapy for patients with PDR,” he says. “It’s impossible to guess who is going to be adherent with regular visits. By five years, only 66 percent of patients in Protocol S followed up, and that was a clinical trial, where there is generally much closer attention paid to these patients.”

| “I think [the physician and patient] can agree in certain cases that anti-VEGF would be a better choice, after taking into account concerns such as treatment burden, cost and the possibility of non-compliance.” — Michael W. |

Dr. Hsu and colleagues have published two studies: one looking at factors that increase the risk of loss to follow-up in PDR patients5 and the other comparing outcomes of PDR in patients lost to follow-up who had PRP and anti-VEGF therapy.6

“Given the outcome results we saw in our second study, I would be devastated if even one patient of mine who had anti-VEGF monotherapy was lost to follow-up and went blind, when that could have been prevented with PRP,” he says. Dr. Hsu emphasizes that anti-VEGF therapy is important, too, however. “I want to be clear that I’m not against anti-VEGF; in fact, I often combine the two treatments,” he stresses. “In cases where patients present with vitreous hemorrhage, I will often start with anti-VEGF until the hemorrhage has cleared enough to permit laser treatment. Also, patients with center-involving diabetic macular edema need anti-VEGF therapy. In both of those scenarios, I’ll try to add PRP as soon as it’s feasible to do so; and I make it very clear to the patient that the injection is only a temporizing measure. In cases of PDR with high-risk characteristics and no vitreous hemorrhage or macular edema, I will go immediately to PRP. But I think every practice also needs to implement a tracking system for these patients, with calls and letters if they miss appointments,” he says.

|

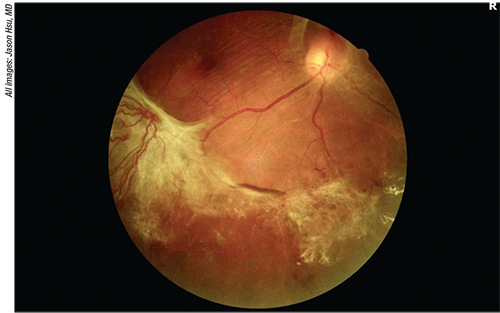

| Figure 1. Fundus photo of a 51-year-old diabetic with no prior treatment who presented with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Severe fibrovascular proliferation can be seen along the inferotemporal arcade of the right eye, causing some retinal striae in the macula. |

“We know that PRP has a more permanent effect on regression of neovascular disease, which has been well documented in long-term follow-up studies,” Dr. Hsu continues. “However, the long-term effects of anti-VEGF therapy on controlling neovascularization are somewhat unclear. The DRCR network five-year Protocol S results indicated that most patients still needed, on average, three injections even in year five, suggesting that anti-VEGF monotherapy will require ongoing treatment in the long run to maintain its efficacy,” he says.

The lack of a predictable endpoint for anti-VEGF monotherapy for PDR lends credence to the continuing role of laser treatment, where feasible. “I worry that if a patient with PDR is lost to follow-up for an extended period of time, he may suffer irreversible vision loss if no PRP has been done,” notes Dr. Hsu. “Even the most reliable-appearing patient has unforeseen events, such as loss of a job, loss of health insurance or an extended illness, since these are by definition sicker patients. As a result, my general goal is to get PRP in as soon as possible in all PDR patients with high-risk characteristics.”

Dr. Hsu says that his study findings convinced him that reliance on anti-VEGF therapy alone puts patients at long-term risk. “What alarmed me most was that when we looked at patients who received either anti-VEGF or PRP, we found that more than a quarter did not return for a year or more—if ever—immediately after the treatment,” he says. “While our study5 identified several risk factors for loss to follow-up, including younger age, African-American or Hispanic race, and lower income based on regional average adjusted gross income from ZIP code of residence, the reality is that these factors do not allow us to predict who is going to return for follow-ups accurately.”

Dr. Stewart agrees that laser offers better control of disease in cases of noncompliance. “In case the patient doesn’t come back, you don’t get a runaway proliferative retinopathy that then leads to permanent vision loss,” he says. “To me that’s an important consideration. One thing that people are now citing as a big factor in favor of laser treatment is that if you take a patient down a road of repeat intravitreal anti-VEGF injections, and then for some reason that patient misses a follow-up appointment—perhaps because they’ve just decided not to come back, or their insurance has changed and they can no longer come back, or because they get sick and they’re unable to return—then once the VEGF drive is turned back on again, there are some patients who’ll develop severe proliferative disease and permanent vision loss as a result,” he says. “But if laser therapy were already in place, that wouldn’t be the case. Some people think that such a reactivation of the VEGF drive is a rebound, and that it may be even more exuberant than it was initially.”

|

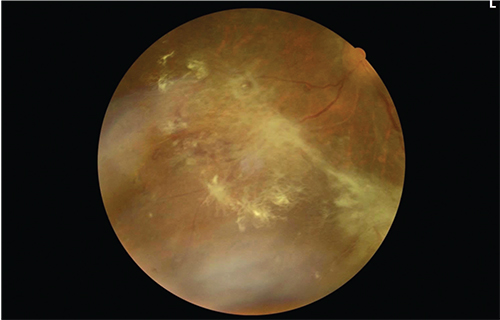

| Figure 2. One year later, the active neovascular component has regressed after panretinal photocoagulation, leaving preretinal fibrosis. Visual acuity is 20/40. |

Dr. Hsu found that anti-VEGF-only patients he followed fared worse than those who’d been treated with laser.6 “Our second study showed that PDR patients who had only received anti-VEGF injections prior to being lost to follow-up had worse outcomes,” he says. “Despite visual acuity being fairly similar just before being lost to follow-up, the anti-VEGF group had poorer visual acuity upon return and at the final visit, even after a period of retreatment. This may have been driven by worsening of the PDR, as we saw a significantly higher rate of traction retinal detachment in the anti-VEGF group upon return and at the final visit, with a third of the eyes developing this complication, versus only about 2 percent in the PRP group. In addition, surgery to repair the TRD was performed in 20 percent of eyes in the anti-VEGF group; while no eyes in the PRP group required TRD repair, suggesting the severity was much greater in the anti-VEGF group.”

The Search Continues

Dr. Stewart says that other laser modalities have been tried in combination with anti-VEGF injections, but they haven’t compared favorably to PRP. “People have pursued peripheral photocoagulation as an adjunct to anti-VEGF therapy for the treatment of macular edema, as a way of downregulating VEGF,” he says. “Thus far, it’s been disappointingly unsuccessful. Theoretically, it makes great sense, but practically it’s just never worked.” He says that micropulse laser therapy doesn’t have robust evidence to back it up at this time, either. “Micropulse is a great treatment,” he says, “but it’s only been used on small numbers of people, and there aren’t any really good randomized controlled trials. The data doesn’t really support the treatment. In fact, it probably has no great advantage over standard laser in terms of visual outcomes.”

With regard to pharmaceutical therapies for PDR, the hunt is still on, says Dr. Stewart. Durability would be an important characteristic of future treatments, since compliance is subject to the fallibility of human nature and the vicissitudes of life. “Real life is always more complicated than a prospective research trial,” he says, “and in proliferative disease, what we’re worried about is the compliance issue. There’s the very real risk of runaway proliferative disease.

| “What alarmed me most was that when we looked at patients who received either anti-VEGF or PRP, we found that more than a quarter did not return for a year or more—if ever—immediately after the treatment.” — Jason Hsu, MD |

“It’s possible that better future treatments would be able to be put into the eye at less-frequent intervals, but we really don’t know how to best define a ‘longer-acting’ treatment,” Dr. Stewart adds. “Would it be six months? Six years? The longer we’re able to have a sustained anti-VEGF effect, then the less potential disadvantage it would have over laser photocoagulation in the long run, but we just don’t have such an agent available yet.”

The quest for a better therapy may go beyond longer-acting anti-VEGF drugs, according to Dr. Stewart. “Somewhere along the way, we’re going to have the ability to reverse diabetic retinopathy,” he says. “The anti-VEGF agents will do that to some degree, in that they’ll reverse what we see as hemorrhages and exudates and things like that, but they don’t really change the underlying perfusion status as much as we’d like. Somewhere along the way, we’re going to get a drug that’s going to help us reverse nonperfusion, and that’s what’s going to result in a true reversal of retinopathy. We don’t know what form that will take, and we don’t know what the biological target would be. But it will be a very attractive treatment option when we have it.” REVIEW

Dr. Stewart receives institutional research support from Allergan and Regeneron; consults for Alkahest; and is on the advisory board for Bayer. Dr. Hsu receives grant support from Genentech/Roche.

1. Stewart MW. Treatment of diabetic retinopathy: Recent advances and unresolved challenges. World J Diabetes 2016;7:16:333-41.

2. Writing Committee for the DRCR Network, Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015:314:2137-2146.

3. Yang C-S, Hung K-C, Huang y-M. Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) and panretinal photocoagulation in the treatment of high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2013;29:6:550–555.

4. Sivaprasad S, Prevost TA, Vasconcelos JC, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): A multicentre, single-blinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2017; 389:10085:2193-2203.

5. Obeid A, Gao X, Ali FS, Talcott KE, Aderman CM, Hyman L, Ho AC, Hsu J. Loss to follow-up in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy after panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. Ophthalmol 2018;125:1386.

6. Obeid A, Su D, Patel SN, Uhr JH, Borkar D, Gao X, Fineman MS, Regillo CD, Maguire JI, Garg SJ, Hsu J. Outcomes of eyes lost to follow-up with proliferative diabetic retinopathy that received panretinal photocoagulation versus intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor. Ophthalmol 2019;126:3:407-13.