Although customized intraocular replacements for a damaged iris have been available for some time outside the United States, it’s only recently that the CustomFlex ArtificialIris, created by HumanOptics in Germany, became the first stand-alone prosthetic iris to receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. To date, there’s still no billing code allowing financial reimbursement for implanting the device, but surgeons are nevertheless pleased to have something to offer patients who need an iris prosthesis.

Here, surgeons who have implanted the device share some of their experience and advice.

Characteristics of the Device

The CustomFlex ArtificialIris is a flexible, biocompatible silicone device indicated for use in adults or children with congenital aniridia and/or iris defects. It has a black, opaque back surface that completely absorbs light, only allowing light to pass through the fixed, central 3.35-mm aperture. Compared to vision with a damaged or missing iris, this improves contrast sensitivity, reduces glare and light sensitivity and eliminates transillumination defects. The Customflex can also improve an individual’s cosmetic appearance by eliminating visible iris defects. The prosthesis is custom-designed to mimic the appearance of the patient’s other (undamaged) iris, based on photographs approved by the patient and surgeon. The pupil opening has an undulated edge resembling that of a natural iris.

When implanting the device, the outside diameter is cut to the appropriate size for the patient’s eye using a trephine. The CustomFlex can be inserted into the ciliary sulcus using a sclerocorneal approach, or via “open sky” during penetrating keratoplasty. (The company notes that the device can also be implanted in the capsular bag.) It comes in two formats: with or without fiber. The former design allows suturing of the device, if needed; the latter design does not.

The FDA approval followed a nonrandomized clinical trial involving 389 patients. More than 70 percent of subjects receiving the implant reported a significant decrease in light sensitivity and glare, and significant improvements in health-related quality of life. Furthermore, 94 percent reported satisfaction with the outcome. Complication rates were low; they included dislocation, strands of device fiber in the eye, increased IOP, iritis and the need for additional surgery to reposition, remove or replace the device.

|

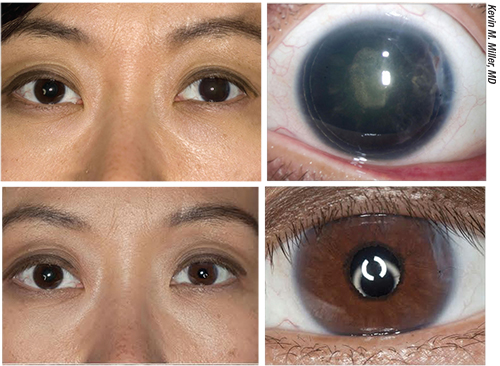

| An example of an excellent outcome. Top images: This patient suffered a blunt injury to her left eye following phakic intraocular lens implantation; the iris and the implantable contact lens were expelled, leaving her aniridic with a cataract. She then underwent cataract extraction with intraocular lens implantation and passive fixation of a dark brown custom artificial iris in the ciliary sulcus. Bottom images: Three months later the color match is excellent and the iris is perfectly centered. |

The Patient Experience

“These can be some of the most gratifying cases an ophthalmologist may encounter,” says Michael E. Snyder, MD, who practices at the Cincinnati Eye Institute and is volunteer assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati School of Medicine. “Patients who get the custom, flexible artificial iris often refer to the experience as being ‘life-changing.’ As one might expect, many folks with iris damage or deformities have suffered with light sensitivity, glare, halos, arcs and monocular shadow images. In the overwhelming majority of patients, most or all of the patient’s photic symptoms are relieved after device placement. How people feel about the restoration of a more normal appearance to their eyes can also be quite dramatic.

“As ophthalmologists, we often don’t appreciate the degree to which patients feel like their vision is washed out because of the iris defects,” he continues. “This is especially true in pseudophakes. As it turns out, any light that enters the eye around the periphery of the IOL margin is defocused. This affects vision much like the experience of being in a movie theater when someone opens the door to the theater, letting light in from the outdoors. Even though the projector is still focused on the screen with the same number of lumens of light, the viewing experience is diminished by the defocused excess light.”

Kevin M. Miller, MD, Kolokotrones Chair in Ophthalmology at the David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, was an investigator during the FDA clinical trial of the artificial iris. Many of the patients he now treats that receive an artificial iris have suffered serious ocular damage, and he notes that it’s not always easy to determine how these patients feel about receiving an artificial iris, because they have so many other ocular problems. “Patients with iris defects typically have suffered trauma, leaving them with a boatload of other issues,” he says. “By and large, these are sick eyes. Their cornea is often decompensating; many have glaucoma as a side effect of the trauma; they may have double vision, a retinal detachment or silicone oil in the eye. An iris defect is just one of their problems. For example, I had a patient whose eye was gutted when a bungee cord snapped and the hook on the end ripped through his eye and lids. Another patient had his globe ruptured by flying glass from a broken bottle. In my experience, 95 percent of the cases needing an iris are like that.”

What about patients whose eyes haven’t suffered trauma? “It’s a rare patient in my practice who is born with some or all of the iris missing, although we do see a few,” says Dr. Miller. “But even those patients have additional comorbidities. A congenital anaridic, born without an iris, may have a limbal stem cell deficiency; the cornea may be hazy; abnormal corneal blood vessels may have grown in; and severe dry eye, epitheliopathy, nystagmus or early cataracts may also be present. Aniridic capsules are thin and easy to tear, and these patients often have glaucoma. So even the nontraumatized eyes have lots of comorbidity.

“Because of that, when we do surgery on these eyes, we try to fix as many of these problems as we can,” he explains. “We might be doing a corneal transplant, lens exchange, cataract removal or a host of other things. The recovery may be long and difficult, not because of the artificial iris, but because of all the other problems. Once a corneal transplant is healed, the patient may have double vision, so we have to fix that. Once we fix the double vision the patient might have a blepharoptosis and we might have to fix that. Some of these problems go on for years and years. As a result, the patient’s feelings about the artificial iris are hard to capture because they go through so much.”

Despite these caveats, Dr. Miller notes that patients are rarely, if ever, unhappy with the artificial iris itself. “Does anybody every regret having had the artificial iris put in? Definitely not,” he says. “The artificial iris solves the light and glare sensitivity problem, and it improves the cosmetic appearance of most patients’ eyes.”

|

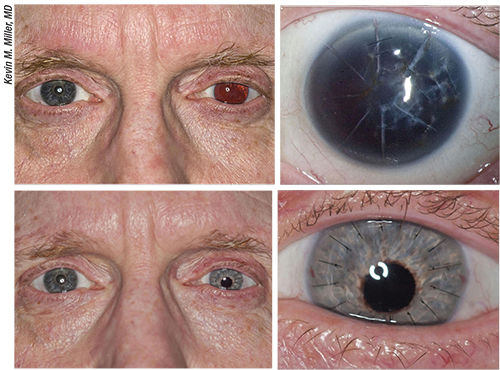

| An example of an imperfect outcome. Top images: This patient suffered a ruptured globe injury that resulted in expulsion of his iris and lens. The injury left him aphakic with a badly scarred cornea and no iris. Bottom images: The patient’s appearance three months after penetrating keratoplasty and scleral suture fixation of a posterior chamber intraocular lens and custom-painted blue artificial iris. The iris is inferiorly decentered and the color match to the iris in the right eye is less than ideal. |

The Challenge of Iris Matching

Although the premise of matching the appearance of the artificial iris to the other eye’s iris makes perfect sense, getting a perfect match is more difficult than it may sound.

“While the devices are custom-made to match an index photo taken of the fellow eye, there can be subtle variations in color and luminosity of the device in different lighting conditions,” Dr. Snyder explains. “The appearance can vary a bit more than native iris tissue. A realistic expectation is that the custom iris will typically look either the same as, or very similar to, the fellow eye at what I call ‘cocktail party distance’ in normal room lighting.”

Dr. Snyder also points out that the actual diameter of the artificial pupil (3.55 mm) is different from the size observed from outside the eye. “What we ophthalmologists usually think of as pupil size is actually the size of the entrance pupil, or the appearance of the pupil as seen through the cornea’s magnification,” he explains. “Accordingly, the apparent pupil size in an eye with an indwelling CustomFlex ArtificialIris is roughly 4 mm.”

“I’d say that after the eye has settled down, most patients are pleased with the cosmetic appearance of the eye,” says Dr. Miller. “However, it’s usually not perfect. In fact, it’s far from perfect for many patients, for two reasons. First, they may have cosmetic issues because of the other problems we’re addressing, such as scarring from a corneal transplant, a misaligned eye or a ptosis. If you have a nice artificial brown iris, but your eye is chronically inflamed because of all the surgeries you’ve been through, you may not feel too good about your eye, regardless of how good the artificial iris looks.

“Second, there are many factors that can lead to an imperfect match with the other eye, despite everyone’s best efforts,” he continues. “Although the artificial irises are hand-painted, the process by which the company paints the iris isn’t perfect. We send photographs of the fellow eye to Germany, where artists paint the prosthetic iris based on the photograph they receive. But you can imagine all of the steps along the way that could result in imperfect color matching, including the lighting when the photo is taken, the color saturation in the image and the spectral sensitivity of the film or digital camera. Then we have to print the image on paper to send it, and the printing process introduces color errors. Last but not least, the brightness is altered a little when you place an artificial iris inside an eye. The cornea focuses a lot of light onto the iris, so it looks much lighter inside the eye than when you hold it in your hand. Of course, we do our best to compensate for all of this, but matching the color and brightness is very challenging.”

How Hard Is It to Implant?

Dr. Miller says the difficulty of implanting the artificial iris varies widely depending on the patient’s situation. “In some cases it’s very easy to implant,” he says. “Sometimes you can just inject it using an AMO Silver

Series injector and unfold it. But sometimes it’s very difficult because of the other issues the eye presents.

|

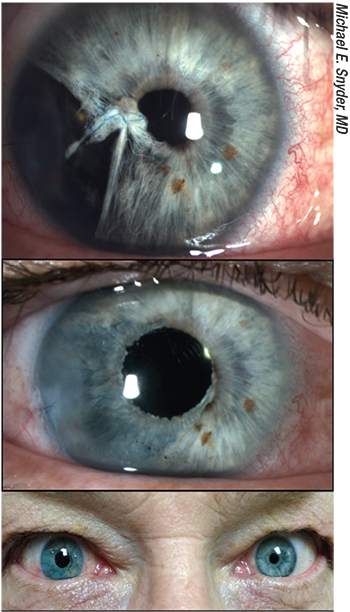

| Even when the color match is excellent and the artificial iris is well-centered, the changing size of the natural iris in the other eye can cause the eyes to be an imperfect match in bright or dim lighting conditions. |

“The company that’s distributing the artificial iris, VEO Ophthalmics, won’t let you implant these unless you meet a number of criteria,” he notes. “For one thing, you have to show that you have considerable experience doing complex ophthalmic maneuvers inside the eye. You have to have experience with lens exchange and related procedures. That makes sense, because these eyes are often very complex, messed-up eyes, and it takes a surgeon with a broad skill set to be able to deal with all of the other issues that may accompany implanting an iris. The company doesn’t want to have surgeons with limited experience attempting to implant these devices and making the eye worse than it was to start with.”

Dr. Snyder says there definitely is a learning curve to implantation. “As with surgery in any complex eye, some cases are harder than others,” he notes. “VEO Ophthalmics, the distributor of the CustomFlex, has developed a rather robust training program; several investigators from the initial study serve as mentors to new implanters. Surgeons who are experienced and facile in complex cases such as scleral-sutured PCIOLs, or cases involving vitreous management in the anterior segment or management of zonulopathy, will find their skill sets will serve them well as they acquire experience working with iris prosthesis patients.”

The manufacturer notes that the CustomFlex should not be implanted in patients who are pregnant, or have an active ocular infection or uncontrolled inflammation; any untreated medical issues that are potentially vision-threatening; rubeosis of the iris; proliferative diabetic retinopathy; Stargardt’s retinopathy; or any disorder that might cause the eye to be abnormal in size, shape or function.

Strategies for Success

Surgeons offer these suggestions to increase the likelihood of ending up with a good outcome and a happy patient:

• Don’t overpromise the result. Patients need to be forewarned that the outcome could be less than perfect, both in terms of appearance and in terms of resolving visual difficulties. “As with any procedure, setting patient expectations is important,” says Dr. Snyder. “It’s worth mentioning that the fellow eye’s pupil size will be changing with ambient light while the custom iris aperture stays constant. As a result, in bright sunlight the fellow eye may have a smaller pupil than the pseudopupil of the custom iris, while in a very dim room, the fellow-eye pupil may appear larger.”

Iris color may also be a giveaway in some cases. “The match [between the eyes] should be close, but the colors will be off a little bit,” notes Dr. Miller. “As a result, in about half of these eyes you can’t tell that the patient has an artificial iris, but in others, you can tell.

“Also,” he continues, “it’s hard to perfectly position the iris inside the eye when suturing it in place. As a result, the pupil is often a little bit off-center. When suturing it in an open-globe configuration, which is what we do most of the time, it’s very hard to center the device. You don’t really know how the iris is going to sit relative to the center of the cornea until the eye is closed up and pressurized. By that point, if it’s not perfectly centered, there’s too much trauma associated with reopening the eye to start over again, so we generally don’t.

“How obvious any decentration is depends partly on the color of the iris,” Dr. Miller adds. “If it’s a light blue or green iris, it can be very obvious when it’s not perfectly centered. If it’s a dark brown iris, nobody can tell.”

Dr. Snyder notes that patients need to understand that the prosthesis won’t address other visual issues. “Eyes that benefit from an iris prostheses also tend to have other comorbid pathologies,” he points out. “Visual limitations are more commonly set by these other factors.”

Dr. Miller agrees. “We have to put this in the context of all of the other problems these patients present with,” he says. “If the patient has a macula-off retinal detachment and a dense cataract and a cornea scar, we’re going to do our best to fix all of this. However, the patient will still have issues postoperatively because of all of these other problems, and there will probably be additional surgeries in the patient’s future. We have to make sure the patient understands this. Don’t oversell the final result.”

• Don’t be shy about deciding to learn the procedure. “If you occasionally treat patients with traumatized or missing irides, this should be part of your armamentarium,” says Dr. Miller. “There is a learning curve, but you have to take the first step at some point. Most of the procedures we do have a prescribed certification protocol that you have to go through, and expanding your skill set is an important part of being a surgeon.

“However,” he adds, “if you only encounter a traumatized or missing iris once a year, it probably makes more sense to refer that patient to another surgeon. You need to do a lot of these surgeries to become good at it, and you won’t become good at it doing one patient every year.”

• Be prepared to implant the iris for free. “If you’re going to get into this, you’re going to be doing it for free for a while,” Dr. Miller points out. “There’s no billing code for this right now, so patients pay for the iris, but the surgeon does the surgery for free.”

• If a cataract patient needs an artificial iris, don’t do the cataract surgery first and then refer the patient for the other procedure. “I’ve had patients referred to me this way, with the best of intentions,” says Dr. Miller. “It may be a simple case, like congenital anaridia with a cataract. The other doctor says, ‘I’ll take out your cataract and it will make you better.’ Actually, it makes them a lot worse. Their glare sensitivity usually gets much worse after the cataract comes out, because now light hits the edge of the IOL implant and the capsule that’s opacified around the implant.

“These patients should have the iris implanted at the same time the cataract surgery is done,” he explains. “Besides leaving the patient with worse vision, separating the surgeries results in a much greater cost to the patient. If we do both surgeries at once, we can bill for the cataract surgery and put in the artificial iris for free. If the only reason for the trip to the OR is to implant the iris, the patient may be looking at a huge bill for both the iris and the trip to the OR. That OR cost would have been covered by insurance if both surgeries had been done at the same time.”

At Last, an Option

As mentioned earlier, the CustomFlex is now being distributed through VEO Ophthalmics. It takes four to eight weeks for the custom iris to be delivered after receipt of the order and the approved photographs.

“I’m glad we finally have an approved artificial iris,” says Dr. Miller. “Only a few patients will need the iris, fortunately, but it’s nice to finally have something we can offer when patients have a messed-up eye. Artificial pupil contact lenses are hard and uncomfortable to wear, and they don’t really solve all of the problems that come with a disrupted or missing iris. The only other alternatives are tinted glasses and patching the eye. Now we have an option that didn’t exist before.”

For more information about obtaining the device, visit veo-ophthalmics.com. REVIEW

Dr. Snyder is a consultant for HumanOptics. Dr. Miller has no relevant financial interests.