The idea of an EDOF lens is to enhance near and intermediate vision without hurting distance vision or inducing as many issues with glare and halo as might be experienced with a multifocal IOL. Sioux City, Iowa, surgeon Jason Jones, who participated in Symfony’s clinical trial, explains the design: “It’s still a single-piece acrylic lens that we’re familiar with from Abbott on the Tecnis platform,” Dr. Jones says. “It has the spherical aberration correction that’s shared across that family of lenses, so the overall design and injection system is familiar. It has a diffractive grating which, on its face, reminds us of a multifocal lens, but there are some significant differences. The ring structures have an echelette formation that elongates the focus area rather than splitting the light.

“The design also allows for less chromatic dispersion,” Dr. Jones continues. “Instead of dispersing it as another lens design might, it helps collapse it to a tight region of focus. This helps improve contrast sensitivity and balance out some of the issues that you might get from elongating the focal length and splitting the light.”

What this design translates into in the clinical study is patients in the Symfony group seeing 1.7 lines better on average at intermediate distances, monocularly uncorrected vs. the Tecnis monofocal IOL group. Monocular distance-corrected intermediate vision is 20/25 or better in 70 percent of the Symfony patients vs. 14 percent of the monofocal patients. At near, 62 percent of the Symfony patients saw 20/40 or better monocularly, distance corrected vs. 16.2 percent of control patients. Average distance vision was slightly better with the monofocal controls, but Dr. Jones says the difference wasn’t statistically significant.

In terms of distance-corrected near vision, Dr. Jones says Symfony patients got a little over two lines of improvement vs. the monofocal lens. “At the 20/40 or better level of distance-corrected near vision, monocularly, you’d see a little over 60 percent of the Symfony patients,” he says. “This compares with 16 percent of the monofocal patients.” Dr. Jones says that, at the six-month visit, 85 percent of the Symfony patients reported wearing glasses “a little or none of the time” in the week prior to the visit.

“There’s also the concern of dysphotopsias with a lens like this,” Dr. Jones says. “Some patients report some dysphotopsias, but it’s a very low rate, perhaps slightly more than a monofocal lens. In comparison to what we’re used to with a multifocal lens, this lens appears to have what I would call a ‘softer’ profile in terms of halo and glare formation. There were no decentrations or glistenings reported.”

The lens was also approved for toric correction. The toric models correct from 0.69 D at the corneal plane up to 2.57 D, in 0.5-D steps.

“For this lens, you want a patient who’s interested in at least reducing his dependence on spectacles,” Dr. Jones says. “If someone wants to wear their glasses, this isn’t a lens you want to choose for them. They also have to be willing to incur some extra cost. At this stage, without a lot of experience with this lens, I’d be more comfortable approaching it as a lens that will give an enhanced range of near and intermediate vision without glasses, but may not give you complete performance without glasses for everything. It should significantly reduce the amount the patient uses his glasses, though. It’s also worth telling the patient he might have some halo and glare that could potentially affect his quality of, and level of comfort with, his vision, just to prepare him for this possibility.”

Shire’s Xiidra Is Approved

On July 11, 2016, Shire (Lexington, Mass.) announced Food and Drug Administration approval of lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5% (Xiidra), a twice-daily eye drop indicated for the treatment of the signs and symptoms of dry-eye disease in adult patients. Shire notes that Xiidra is the only prescription eye drop indicated for the treatment of both signs and symptoms of dry eye.

According to the company, the inflammation associated with dry eye is thought to be primarily mediated by T-cells and associated cytokines. One effect of this process may be overexpression of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 in corneal and conjunctival tissues, which may contribute to T‑cell activation and migration to target tissues. Although the exact mechanism of action of lifitegrast is not known, in vitro studies demonstrated that it may inhibit T‑cell adhesion to ICAM‑1 in a human T-cell line and the secretion of cytokines in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

The safety and efficacy of Xiidra were studied in 1,181 patients in four placebo-controlled 12-week trials; 1,067 patients received lifitegrast 5%. Each of the four studies assessed the effect of Xiidra on both the signs and symptoms of dry eye at baseline and weeks two, six and 12. In all four studies, a larger reduction in eye dryness score was observed with Xiidra at six and 12 weeks; in two of the four studies, an improvement in EDS was also seen with Xiidra at two weeks. At week 12, a larger reduction in inferior corneal staining score, favoring Xiidra, was observed in three of the four studies. The most common adverse reactions reported in 5 to 25 percent of patients were instillation site irritation, altered taste sensation (dysgeusia) and reduced visual acuity.

Edward Holland, MD, professor of clinical ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati and a clinical trial investigator for Xiidra, says the approval is a boon to clinicians. “There have been more than 20 dry-eye trials that failed to reach significance in both signs and symptoms,” he says. “Credit goes to the Shire folks for designing a trial that got across the finish line with both signs and symptoms of dry eye.”

Dr. Holland explains that the reason Shire succeeded where others failed was their trial design. “Everyone else tried to achieve significance in both signs and symptoms in the same patient population,” he says. “Shire realized that wasn’t going to work. So the Shire scientists analyzed the data and saw that one group of patients did very well clearing the clinical sign of corneal staining, while another group had symptoms significantly reduced. So they did two separate trials and then repeated both of them. This was a totally new strategy. It made the timetable much longer and the number of patients much greater, but it certainly worked for them, and it might work for other formulations as well.”

Asked how he expects Xiidra to fit into his armamentarium, Dr. Holland says he expects it to be first-line. “Artificial tears are palliative,” he notes. “This is a very effective anti-inflammatory that gets at the pathogenesis of dry eye. For me it will be primary therapy.”

Shire expects to launch Xiidra in the United States in the third quarter of 2016.

Humira Cleared for Uveitis

In mid-July, the FDA approved AbbVie’s non-steroidal immunomodulatory agent Humira (adalimumab) for use in non-infectious intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis and panuveitis. This approval finally gives ophthalmologists an approved immunomodulatory option, obviating the headaches involved with using such agents off-label.

The approval was based on the results of two large-scale, Phase III studies, VISUAL-1 and -2. “VISUAL-1 was designed to test Humira in patients with active uveitis, with the goal of seeing if patients with active inflammation—despite being on steroids—could be tapered off their steroids while Humira helped fight the inflammation,” explains Glenn Jaffe, MD, chief of the retina division at Duke University, and Robert Machemer, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Duke and consultant to AbbVie. “The other study, dubbed VISUAL-2, recruited uveitis patients whose eyes were quiet because they were currently on steroids, with the goal being to get them off the steroids and to substitute the Humira.” The main endpoint in VISUAL-1 was the time until treatment failure. In VISUAL-2, the researchers wanted to see how likely a flare-up would be as patients were tapered off the steroids and kept on Humira.

“The way I think of the results of the VISUAL-1 study is the phrase, ‘twice as long or half as likely,’ ” says Dr. Jaffe, “meaning that the time to treatment failure was about twice as long—24 weeks for the treatment group vs. 13 for the placebo—and the likelihood of getting failure was approximately half for the Humira group. In many cases, the Humira group didn’t fail. So, not only did it take longer, in general, for them to get a flare-up, but they were half as likely to get one, as well.

“Similarly, in VISUAL-2, the study in which the patients’ inflammation was quiet with systemic steroids to begin with, the idea was to see if patients were less likely to get a flare-up if they were treated with Humira than if they weren’t,” Dr. Jaffe continues. “Both studies mandated a steroid taper over 15 weeks. In VISUAL-2, the patients who were switching over to Humira were significantly less likely to have treatment failure when the steroids were tapered, and they had less of a chance of visual acuity going down.”

In terms of the best patients for the use of Humira, Dr. Jaffe notes that a risk of infection always lurks whenever an immunomodulatory agent is used. “Certainly, if someone has a history of tuberculosis, especially if it’s not treated, you don’t want to put him on one of these agents,” he avers. “However, you can cautiously treat someone with TB as long as it’s been completely treated, but that’s something you have to confirm before starting these agents. Also, in general, I’d say patients with an underlying infectious cause of the uveitis wouldn’t be good candidates.

“The tumor necrosis factor inhibitors like Remicade and Humira can potentially cause a flare-up of multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating diseases,” adds Dr. Jaffe. “Also, individuals who have intermediate uveitis are at an increased risk of having MS as an association with the inflammation. In intermediate uveitis patients, I’d recommend a brain MRI to ensure there’s no evidence of MS.”

FDA Approves The Raindrop

Surgeons now have a new option for their presbyopic patients, thanks to the Food and Drug Administration approval of ReVision Optics’ Raindrop Near Vision Inlay in July. The inlay is designed to give patients improved near and intermediate visual performance, and was approved based on the results of a one-year prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter clinical trial.

|

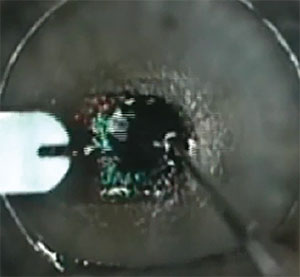

The Raindrop inlay is implanted beneath a LASIK flap, and its presence steepens the cornea, yielding greater depth of focus. |

Dallas surgeon and Raindrop investigator Jeffrey Whitman, MD, says the inlay did give presbyopes a wider focal range. “The question is, does it work for reading?” he says. “Yes. It does well for intermediate, as well. In this day and age people aren’t really looking for just distance and close up. They’re looking at their phones and computers, and the inlay does well at that distance.”

The inlay uses corneal shape change—not refractive power—to get its effect. “It’s a 2-mm-diameter, meniscus-shaped inlay with an index of refraction that’s equal to the cornea’s,” explains Dr. Whitman. “It’s 30 µm thick in the center. The Raindrop works by steepening the center of the cornea, which gives you a greater depth of focus.” It’s approved for use in the non-dominant eye of patients with a manifest refraction spherical equivalent of -0.5 to +1 D, with 0.75 D or less of cylinder. The inlay is approved for implantation beneath a LASIK flap at one-third corneal depth, and a corneal pocket study is imminent. Though it’s not approved for it, surgeons may opt to perform LASIK beforehand to get patients in the emmetropic range and then implant the inlay.

The study looked at 373 non-dominant eyes of emmetropic, presbyopic subjects that received the Raindrop at 11 sites. During the one-year follow-up visit, researchers studied 340 of the nondominant eyes.

“By one year 93 percent of subjects were 20/25 or better at near. They gained an average of 5.1 lines of reading vision,” Dr. Whitman says. “So, it was pretty dramatic; 97 percent of subjects saw 20/30 at intermediate distance postop. The inlay is clear, so there’s very little loss of contrast sensitivity and no loss of binocular vision.”

At one year in the treated eye, uncorrected intermediate visual acuity improved by 2.5 lines while best-corrected distance visual acuity decreased by 1.2 lines. From three months through one year, 93 percent of subjects achieved uncorrected near visual acuity of 20/25 or better, 97 percent achieved UIVA of 20/32 or better and 95 percent achieved UDVA of 20/40 or better. Binocularly, the mean UDVA exceeded 20/20 from three months through one year.

Dr. Whitman says the procedure is straightforward. “You lift the flap up and place the device over the light-constricted pupil. Wait about a minute for it to dry in place before putting the flap down. Then let it dry as you would a normal flap. Then, there’s the recommended drop regimen afterward that’s similar to LASIK’s.”

In terms of candidates for the inlay, Dr. Whitman states, “If they’re not healthy enough to be a LASIK candidate, they aren’t a good candidate for this. Because, basically, the issues relate to flap technology.”

Dr. Whitman says adverse events were low in the study. “Visual symptoms such as glare and halo had less than a 4-percent incidence,” he says. “Eighteen inlays were replaced, most of those for decentration. After replacement, they had the same uncorrected near vision as the rest of the study population. Eleven cases required explantation, for reasons such as decentration, dissatisfaction with vision and foreign-body reaction. Only one eye experienced the foreign-body reaction. The foreign-body reaction can usually be treated with steroids, but if it persists, in the study we recommended removal of the inlay. You can remove it and patients get back to within one line, on average, of their best-corrected vision within three months.” REVIEW