In addition, a procedure's ultimate success depends on two factors: surgical technique and the eye's response to the surgery. In some cases, such as trabeculectomy, healing can be problematic; rapid healing will cause fibrosis and lead to failure of the bleb. In other instances, such as when implanting a tube shunt, healing allows success. (Without the healing process, the tube shunt would be a catastrophic process leading to marked hypotony.)

Here, I'd like to discuss each of the most commonly used surgical options in greater detail, to shed light on what makes them a good choice—or poor choice—in any given situation.

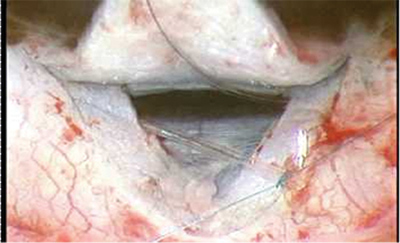

Trabeculectomy

Despite alternative options, trabeculectomy, or a guarded filtration procedure, is still the gold standard for surgical treatment of this disease. It's a first-line surgery for patients with many types of glaucoma, including primary open-angle, pigmentary, exfoliative and chronic angle-closure glaucoma.

The main reason trabeculectomy is the gold standard is that success rates can be as high as 80 to 90 percent (depending upon how you define success), and when it's successful, it's the best at controlling intraocular pressure. In addition, it allows you more control over the outflow than other current surgical alternatives.

Imperfect titration of outflow is a disadvantage shared by all the glaucoma surgeries currently in common use. However, a trabeculectomy lets you adjust the rate of fluid flow through your scleral flap by adjusting the sutures used to close the wound. You can allow almost no fluid egression in the early postop period; then, as the patient heals, you can eliminate sutures to increase outflow by lysing standard sutures with a laser, or by placing releasable sutures during surgery and pulling them out later at the slit lamp.

Despite these good points, trabeculectomy has its limitations:

• The use of anti-metabolites (primarily mitomycin-C) to mitigate healing has enhanced the success rate, while simultaneously opening the door to complications such as bleb leaks, long-standing hypotony, blebitis and endophthalmitis.

• In the glaucomas associated with inflammation or neovascularization, trabeculectomy may not be a good first-line procedure because eyes with inflammation or a neovascular process have increased scar formation. In those situations, an aqueous tube shunt may be a better primary surgery.

• The availability of healthy tissue limits the number of trabeculectomies you can perform on a patient. A trabeculectomy requires at least a section of healthy tissue in order to do the surgery because you're creating an outflow pathway. You need to have mobile, healthy conjunctiva to cover the tunnel so you don't end up with leaks.

• Although trabeculectomy is the most titratable of all the commonly used surgical options, it is certainly not an exact titration.

Tube Shunts

In most cases, an aqueous tube shunt is used as a second-line surgery when a previous trabeculectomy, or trabeculectomies, have failed. The main strength of this option is that it's more resistant to failure in the presence of serious inflammation. Tube shunts can be divided into two categories: Some, such as the Ahmed Valve, have a built-in resistor to limit outflow; others, such as the Baerveldt implant or Molteno shunt, have no valve to restrict outflow.

A tube with a resistor in it to limit outflow has two main advantages. First, it can be placed in a single-stage procedure without risking uncontrolled hypotony, which is not the case with the valveless implants. Second, because it's functional without waiting for fibrosis to restrict flow, it allows operation of the device in the immediate postop period.

In canaloplasty, a new glaucoma surgical option, a filament is inserted into Schlemm's canal and tied; the tension opens the canal, allowing increased aqueous outflow.

The downside to some of these valved implants is that the devices are not perfect; they can still be very leaky, despite the valve, allowing a significant degree of postop hypotony. For this reason, the majority of people who place an Ahmed shunt into the eye, for example, place viscoelastic in the eye to help support the eye for the first few days after surgery. Sometimes, even with viscoelastic in the eye, there's a significantly low IOP in the immediate postop period.

In contrast to shunts that contain a valve, control of IOP in nonvalve surgical devices is dependent upon fibrosis—the encapsulation of the scleral plate, which can take several weeks to occur. If one of these shunts were left fully operational in the immediate postop period, there would be a great risk of hypotony because there would be free flow of fluid out of the eye.

For that reason, some method of flow restriction is used during the early postoperative period when implanting a nonvalve shunt. This can be done in a true two-stage surgical procedure, by placing the scleral plate on the surface of the eye and then returning several weeks later to place the tube inside the eye. The tube may be tied in the anterior chamber with a non-absorbable suture that can be cut at a later time using a laser; often, a stent suture in the lumen of the drainage implant tube is used to restrict flow. Also, the tube may be tied off with a dissolvable suture that allows fibrosis over the scleral plate to take place over several weeks. Then, when the suture dissolves, the tube opens.

Once again, the issue of titration is the major concern. With tube shunts, you are clearly at the mercy of the device, whether or not it has a valve. I don't mean to imply that this option is a bad choice; with both the Baerveldt shunt and the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve, success rates with some types of glaucoma are as high as 80 to 90 percent at one year, and may still be as high as 70 percent at five years. (Comparative studies regarding different glaucoma drainage implants are pending.)

New Options

New types of shunts, and new ways to use them, continue to appear; many are still investigational. These include the Glaukos stent, the GMP Bi-Directional Glaucoma Implant, the Trabectome and the SOLX glaucoma system. An improved safety profile is the impetus for most of these approaches.

Some of these surgeries try to enhance the eye's own native outflow system to control IOP by placing a tube at Schlemm's canal, either ab internally or ab externally; these are closed-system surgeries. They bypass the main site for outflow resistance, believed to be the juxtacanalicular area, by placing a tube there or by stripping the trabecular meshwork. The safety advantage is that the surgeries use the eye's own outflow system, so the procedure should not produce postop hypotony or cause the breakdown of overlying tissue that can allow infection.

The disadvantage of this approach is that you still have to overcome the resistance that's already inherent in the system within Schlemm's canal and in the collector channels, as well as the episcleral vasculature that the fluid will drain through. You're also working against episcleral venous pressure, estimated to be about 9 mmHg. Given these conditions, it's reasonable to expect these devices to have some effect, perhaps lowering the IOP into the mid to high teens, which may be fine for many patients. But for patients with more advanced disease, the goal is to lower pressure more. (Trabeculectomy with an antimetabolite may get the pressure down into the 10- to 12-mmHg range.)

The SOLX glaucoma system, currently approved in Europe, includes a new laser and a shunt designed to be titratable, with multiple microchannels that can be opened one at a time using the laser. Placed through a limbal incision, it forms a bridge between the anterior chamber and supraciliary space. This should avoid problems associated with blebs, but could cause other concerns such as bleeding, choroidal effusion or hypotony.

Trabeculectomy vs. Tube Shunt

Because tube shunts are relegated to use later in treatment, they're often used in eyes that are complex and have scarring. The fact that they can be used under these conditions is an advantage, of course, but they might have a higher success rate if they were used earlier in the pathologic state.

For example, data from the recent Trabeculectomy vs. Tube Shunt Study was presented at the American Glaucoma Society meeting that took place in March of this year. In the study, patients who had already had cataract surgery or a trabeculectomy, or both, were randomized to receive either a Baerveldt tube shunt or a trabeculectomy with mitomycin-C, to see which produced better outcomes. At one year, the tube shunt and trabeculectomy groups had similar IOPs—approximately 13 mmHg. The trabeculectomy group used fewer glaucoma medications, but showed a higher failure rate of 14.8 percent, vs. 3.9 percent in the tube group. Another study comparing the Ahmed Valve to trabeculectomy found that trabeculectomy produced lower pressures during the first year, but that pressures were comparable in the long run.1

Cyclodestructive procedures

Cyclodestructive procedures use lasers to burn the ciliary processes so they make less fluid. Typically, these procedures are third-line, when trabeculectomy or a tube shunt are not good options.

The advantage of contact transscleral diode photocoagulation is that it can be done in the office under local anesthesia, and it's not taxing to the patient or the physician. (Endolasers can also be used in the operating room.) A laser cyclodestructive procedure is a good option in eyes that have reduced visual potential and have been refractory to other treatments.

The downside to a cyclodestructive procedure is that it's the least titratable of all the procedures; you can't be absolutely certain of the extent of damage you're causing. This is particularly true when using the transscleral G-probe; you just place it on the surface of the eye and administer energy. This is important because you're destroying a part of the eye that makes fluid that provides nutrition to the anterior segment. So, you're actually reducing the oxygen supply to the eye and causing chronic inflammation.

Also, long-term effectiveness is difficult to predict. In some cases you'll see a nice response that fades over time and you'll have to repeat the treatment. Other times, to get the pressure down you need to do a lot of initial treatment. This can have serious consequences, particularly with a neovascular patient; sometimes the eye will end up phthisical.

Nevertheless, cyclodestructive procedures have a reasonable success rate in complex eyes; in fact, in some patients, this is the only approach that has worked. So a cyclodestructive procedure is often used in end-stage eyes—eyes that have had an ischemic central retinal vein occlusion, or a neovascular glaucoma with very poor visual potential. In any case, these laser procedures are superior to the older cyclocryotherapy or freezing procedure, which had a much higher level of ocular morbidity.

Nonpenetrating Surgery

Like several other approaches, nonpenetrating surgical options have evolved to provide an alternative to trabeculectomy. Unlike trabeculectomy, nonpenetrating surgeries—most commonly, viscocanalostomy or deep sclerectomy—don't create a full-thickness hole into the anterior chamber. By avoiding this, nonpenetrating surgery avoids the problem of postop hypotony by only allowing a slow percolation of fluid out of the eye. At the same time, it may limit the resulting reduction in IOP.

(Note: For a more in-depth discussion of nonpenetrating surgical options, see "Making the Case for Nonpenetrating Surgery" from the September, 2005 issue of Review, at revophth.com/index.asp?page=1_794.htm.)

Recent surgical alternatives, some of which are still investigational, include the Trabectome, Schlemm's canal tube surgery, and transcilliary filtration using the Fugo blade. These may provide surgeons further options in the management of this complex condition.

Dr. Costarides is Pamela Humphrey Firman Professor of Ophthalmology at Emory Eye Center in Atlanta.

1. Wilson MR, Mendis U, Paliwal A, Haynatzka V. Long-term follow-up of primary glaucoma surgery with Ahmed glaucoma valve implant versus trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136;3:464-70.