I think most ophthalmologists, especially glaucoma specialists, aren’t entirely satisfied with trabs and tubes. We still rely on them, in part because when glaucoma is severe, the risk/benefit ratio tilts in favor of doing the surgery, despite the potential complications. But that doesn’t make them ideal, and it raises the question of what we can do for patients who only have a mild-to-moderate degree of severity—patients we don’t want to put at high risk of complications with a trabeculectomy or tube. We need an in-between procedure, one that’s safe and effective for patients with mild-to-moderate glaucoma. That need accounts for the current interest in the minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, or MIGS procedures.

Given that new procedures are now available, many ophthalmologists are wondering whether it makes sense to incorporate one of them into their practice. I’d like to offer some help answering that question.

To Add or Not to Add?

To decide whether it’s a good idea to add a new surgery to your glaucoma armamentarium, it helps to assess your practice needs, as well as your patient population, from both a practical and financial standpoint. Questions worth asking include:

• Are you satisfied with your present surgical options? I believe most surgeons are well aware of the shortcomings of traditional surgeries such as tubes and trabs. Nevertheless, if you do trabeculectomies and get a pressure of 10 mmHg every time, with no complications, you might not feel the need to have alternative options. Unfortunately, I don’t think most of us fall into that category; we do have some problems and complications, and our outcomes don’t always meet our expectations. For us, trying new surgeries may be a sensible option.

• Do these surgeries fit your patient demographics? For most surgeons, tubes and trabs are not ideal for patients with mild glaucoma—patients who don’t really need the low pressure that a trabeculectomy or tube might provide. Many of the new alternative surgeries don’t produce very low intraocular pressures; but if you can lower the pressure somewhat, with fewer complications, that’s a potentially useful trade-off for these patients.

|

| When deciding whether to add a new surgery to those you offer, consider how well your current procedures are working; what percentage of your patients would be better-served; how a new procedure will fit into your current surgeries; your surgical skill level; the cost; and whether your patients will be able to manage the postoperative care requirements of the new surgery. |

This could be especially important as we move forward, because it’s possible that the number of these patients will increase significantly. Currently, a lot of patients don’t end up getting surgery until their glaucoma is already advanced. Hopefully, 10 years from now, people will be better-educated about glaucoma and more glaucoma will be discovered before it reaches the severe stage. If that’s the case, we’ll be seeing more people who have mild-to-moderate glaucoma, some of whom will need an option beyond medications. These less-risky procedures could be ideal in that situation.

• Do these surgeries fit in with your current procedures? Many of the surgeons using MIGS procedures right now are primarily cataract surgeons. These procedures are a good fit for them, for several reasons. First, many cataract surgeons don’t feel comfortable doing trabeculectomies. Second, most of their glaucoma cases aren’t very severe; they just need a few more points of pressure lowering to get the patient off medications. Third, adding a MIGS procedure is just a slight modification of what they’re already doing. So for them it’s a fairly easy transition to add the new procedure. (That’s not to say the new procedures have no value to a glaucoma specialist. I do cataract surgeries too, and some of my patients don’t have severe glaucoma.)

Which Surgery to Add?

If you want to try adding a new procedure to your armamentarium—perhaps the iStent, the Trabectome, canaloplasty, the ExPRESS shunt or ECP—a head-to-head comparison of their efficacy would be ideal. Unfortunately, at this point that doesn’t exist. There aren’t a huge number of good studies that have compared procedures; most reports concern a series of patients who had one type of procedure.

In lieu of that, a number of factors should be considered when deciding which one(s) to add:

• Your surgical skill level. If you’re a very good surgeon, you can probably try any new procedure that interests you. If not, you may want to think twice about trying new surgeries that come with a big learning curve.

• Cost considerations. These can be important, depending on what your financial setup is with your surgical center, because many of these new procedures have upfront costs for equipment. They may also have per-case costs; you may have to pay for each device you implant, and/or there may be a disposable part of the equipment that must be replaced each time, such as the light pipe in canaloplasty. There may also be costs involved in training your staff.

• How far your patients have to travel. This is relevant because some of the new procedures have fewer postoperative requirements in terms of visits. If a patient is coming a long distance, perhaps from several hundred miles away, then it would make sense to favor a procedure that doesn’t require as many postoperative visits, or one that’s simple enough that the referring physician can manage the postoperative care. (That’s another disadvantage of trabs and tubes; they do require a fair number of postoperative visits and maybe even some additional procedures during the postoperative period.)

Learning a New Surgery

Once you’ve chosen a surgery to learn, you have to decide how to develop the skills connected with that procedure. Fortunately, many of the newer procedures have evolved from earlier, more familiar procedures, which means that skills we already possess may be stepping-stones to move us into the new skill set. For example, canaloplasty is based upon several other surgeries that have been developed over the past 20 years, including trabeculectomy, deep sclerectomy and viscocanalostomy, in which you identify Schlemm’s canal and inject viscoelastic into it.

Because most of the new surgeries are built upon previous surgeries, you can practice each step as you’re doing a traditional surgery until you’re ready to try the newer technique. When doing a trabeculectomy, for example, you can gradually practice the skills needed to perform canaloplasty. During trabeculectomy we normally just create a scleral flap and then do the sclerostomy. But before doing the sclerostomy, you can do a deep sclerectomy, which means removing a deeper block of sclera so you’re left with a thin layer of sclera overlying the choroid. You can dissect that anteriorly until you get a little bit of a Descemet’s window, and stop there; doing this will give you practice dissecting a deep sclerectomy. Each time you do it, make a bigger Descemet’s window and start looking for Schlemm’s canal. You can still go ahead with the trabeculectomy; just do what you would normally do. The extra step won’t affect your surgery very much, but it will give you practice doing the deep sclerectomy. This will allow you to develop the skills you need to perform canaloplasty gradually, over a period of months. Eventually, performing canaloplasty won’t be difficult at all.

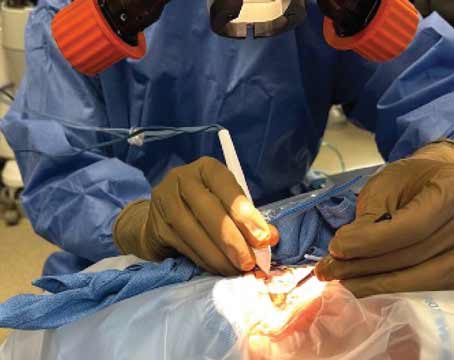

Similarly, to prepare to implant an iStent you can practice identifying the angle at the end of cataract surgery. Simply adjust your microscope and use the gonioprism; see if you can identify the angle, and get comfortable with that positioning of the microscope and your hands and the gonioprism. Once you’ve done that a few times and you feel comfortable doing it, you can move on to inserting an iStent.

Sometimes learning to perform one of the new surgeries will help prepare you for others. This is true for angle surgery. Once you’ve learned to use the Trabectome or the iStent, you’ll find it much easier to try the other devices that are going to be coming out very soon—including suprachoroidal devices, or even the new GATT technique (gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy) and ab interno canaloplasty.

| I don’t think tubes or trabs will ever disappear from our toolboxes, but I believe eventually they’ll be relegated only to the severe cases. |

Making Our Way Forward

One of the most interesting side effects of these new procedures is that they’ve made us rethink what we know about trabecular outflow—how fluid gets out of the eye. When performing trabeculectomy as our main surgical option, we don’t have to think about how the fluid gets out of the eye; we just make a new opening. In the past it was widely believed that resistance to outflow was primarily at the meshwork, so we thought that putting a hole in the trabecular meshwork to create better access to Schlemm’s canal would drop the pressure quite a bit. The mixed results of these new procedures are calling that into question. So, whether or not any given procedure stands the test of time, it’s clear that their use will move our understanding of the disease forward.

In the meantime, the reality is that tubes and trabs are still the bread-and-butter procedures for most glaucoma specialists. None of the newer surgeries have become major players—at least so far. I’ve tried several of them myself, and so far I haven’t been that impressed with the outcomes. But many of these surgeries are just the first generation; new surgeries continue to be developed, and every new iteration tends to be a little bit better than the previous ones. The hope is that something will come along in the next five or 10 years that will be very effective and safe.

I don’t think tubes and trabs will ever disappear from our toolboxes, but I believe that eventually they’ll be relegated only to the severe cases. At that point, the newer procedures will routinely be used to address the mild to moderate cases. In the meantime, I believe it’s good for us to have multiple options, and to be trying different things. REVIEW

Dr. WuDunn is a professor of ophthalmology at the Eugene and Marilyn Glick Eye Institute, Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. He is an investigator for InnFocus, maker of the MicroShunt glaucoma drainage implant.