Shire claims that Allergan has squeezed Xiidra out of the Medicare market by offering Part D plans drastic discounts and/or rebates across a range of its pharmaceuticals, in addition to Restasis, in exchange for maintaining Restasis in a preferred-tier position on their formularies. “Through a combination of anticompetitive bundling and exclusive dealing arrangements, Allergan is coercing Part D plans representing over 70 percent of the Part D market for prescription DED medications to effectively exclude Xiidra from, or severely restrict Xiidra on, their formularies, while at the same time maintaining Restasis—Allergan’s 15-year-old and clinically inferior drug—on a ‘preferred’ formulary tier,” the complaint alleges.

Shire claims that Allergan has accomplished this shutout of Xiidra by offering Medicare Part D plans discounts and rebates spanning a portfolio of its drugs, so that when Shire offered multiple Part D plans substantial discounts and rebates to place Xiidra on their formularies, the plans declined. Shire alleges that Allergan’s hold was so all-encompassing that one Medicare Part D representative advised, “You could give [Xiidra] to us for free, and the numbers still wouldn’t work.”

Shire contends that Allergan is anxious to preserve the larger market share of its “mature cash cow,” Restasis, which it says netted Allergan $1.487 billion in sales for 2016 alone, producing more revenue than any other drug made by the company with the exception of Botox. While Restasis is approved for deficient tear production in dry-eye disease, Xiidra received a broader indication from the FDA, for the signs and symptoms of DED generally. Per goodrx.com, 30-day supplies of the drops have very similar average retail prices: $578.38 for Xiidra; $574.99 for Restasis.

Restasis was the only FDA-approved topical eye drop for the treatment of chronic dry eye from 2002 until 2016, when Xiidra was approved. Shire says that Xiidra claimed 20 percent of the prescription dry-eye market in its first six months of availability. Estimates place the chronic dry-eye population in the U.S. as high as 16 million people, although one million or fewer are thought to be receiving treatment.

An emailed request to Allergan for comment was unanswered, but Allergan spokesman Mark Marmur has stated that the lawsuit lacks merit, and that the manufacturer’s pricing of Restasis to Medicare Part D and commercial plans flows solely from natural competition in the dry-eye market.

The antitrust complaint comes on the heels of Allergan’s unorthodox decision to transfer its six patents related to Restasis to the St. Regis Mohawk tribe in New York State on the grounds that the tribe’s sovereignty would protect the Restasis patents from inter partes review of their validity; legal challenges from other manufacturers seeking to formulate generic equivalents of Restasis have also been in play. The contenders include Teva Pharmaceuticals, Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Akorn and Apotex. The tribe got $13.5 million up-front for taking possession of the Restasis patents and licensing them back to Allergan and expected another $15 million annually for as long as the patents were valid.

On October 16, 2017, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas invalidated four of the six Restasis patents. The decision also characterized Allergan’s deal with the St. Regis Mohawk as the “renting” of tribal sovereignty to serve as a shield from IPRs. As a result, a compounded version of the drug from Imprimis has already appeared at a steeply discounted price compared to Restasis.

Does ALS Affect The Retina?

A combined team of ophthalmology and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis researchers hope their retinal findings in patients with ALS eventually lead to a way to diagnose the disease earlier.

Henry Tseng, MD, PhD, a glaucoma specialist and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Duke University, is researching the mechanism of visual loss in glaucoma and how glaucoma relates to other neurodegenerative diseases. “Since I’m an eye doctor, people would ask me, ‘Why are you studying ALS?’” Dr. Tseng says. “The answer is that one of the most exciting recent discoveries is that three glaucoma genes have also been linked to ALS. There seems to be something going on at the cellular level that may show a commonality between the diseases. This came as a total surprise to basic scientists and clinicians alike.”

To try to build upon this finding, Dr. Tseng formed a joint research study with Richard Bedlack, MD, PhD, director of Duke’s ALS clinic. “We didn’t know if there were any ocular changes in patients with ALS, let alone glaucoma changes,” Dr. Tseng avers. “That’s why we undertook this study.”

To make sure the study results carried weight, the researchers first examined the ALS patients to ensure there were no eye diseases that could cause retinal changes. They also made it a point not to use any exotic technology. “We didn’t want to use a lot of research tools that clinicians can’t use in their offices,” Dr. Tseng says. Twenty-one ALS patients passed the exclusion criteria, and the results the researchers found surprised them.

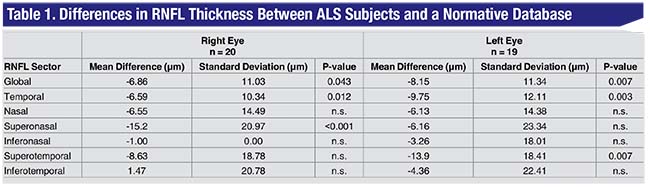

“We found that, despite the patients having no eye diseases that could explain any retinal changes—especially thinning on OCT—these patients did, in fact, show differences,” Dr. Tseng says. Specifically, they found statistically significant retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in the bilateral mean total RNFL thickness, temporal thickness, right superonasal thickness and left superotemporal thickness, as well as an overall trend toward RNFL thinning in all retinal sectors and the global mean retinal thickness (See Table 1).

The upshot of the study is the strengthening link between the retina’s neurons and others in the body. “This result suggests that it’s possible that neurons in the eye have more in common with neurons such as the motor neurons affected by ALS at the cellular/molecular level than we thought,” Dr. Tseng says. “Also, just like we do in glaucoma, ALS researchers are always looking for biomarkers for the disease, and the eye is the only place in the body where you can actually just look in and examine brain cells. This study shows that it may be possible to use the eye as a reliable biomarker for ALS, for diagnosing and potentially monitoring treatment and progression. Eventually, it would be great if we could study the possible clinical link between ALS and glaucoma, and perhaps get some clues as to why patients go blind.” The study researchers only “briefly” looked at the possible association between RNFL thickness and ALS severity, but that could be the subject of future studies.

|

Future studies will include more patients, and hopefully lead to even stronger conclusions. “If we have other groups involved, we could get more patients,” Dr. Tseng says. “The study could possibly be large enough to study whether specific eye diseases are associated with ALS.” REVIEW