The patient was diagnosed with a Dua class VI ocular surface burn (Roper-Hall class IV) of the right eye. A

|

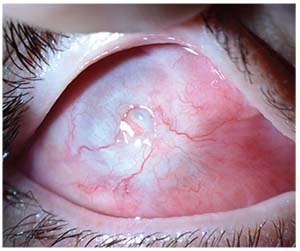

| Figure 4. External photograph of the right eye at month six shows dense pannus 360 degrees and symblepharon superonasally. |

The patient followed up several times in the intervening weeks and required lysis of symblepharon at the slit lamp, but over time he experienced slow conjunctival re-epithelialization and improved to counting fingers. The ProKera was replaced approximately one month after his injury. Around seven weeks after the initial injury the patient underwent lysis of symblepharon, double-layered sutured amniotic membrane transplant, intraoperative ProKera placement, temporary lateral tarsorrhaphy and suture of his old corneal laceration in the operating suite. About a month later he underwent further lysis of symblepharon, repeat amniotic

|

| Figure 5. External photograph of the right eye at month six shows dense inferior pannus with symblepharon inferiorly. |

Discussion

Ocular chemical injuries are a very common occurrence and a frequent cause of urgent ophthalmic evaluation. More than 15,000 chemical eye injuries occur in the US every year, with an average age of 35 and a 2:1 ratio of males to females.1 The classic teaching is that alkali injuries penetrate the ocular surface more readily through saponification of cell membranes. Acid injuries tend to coagulate surface proteins more, limiting penetration.

When faced with severe chemical injuries, the most important treatment is immediate irrigation with a neutral pH solution. When receiving calls from patients or community emergency care centers, which are routinely the first destination for these patients, it is important to emphasize that irrigation must start immediately. The patient should be irrigated until the pH of the ocular surface is 7 to 7.5 before discharging or transferring him for further ophthalmologic care. There have been several studies demonstrating the efficacy of buffered solutions for achieving faster normalization of pH in these cases.2 However, it’s important not to try to “neutralize” alkali injuries with acid solutions or acid injuries with basic solutions, as this can cause further harm.

On ophthalmologic exam, sweep the fornices to remove any particulate matter that may be embedded. The size and shape of the corneal and conjunctival epithelial defects should be measured and documented, paying special attention to the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva. Clock hours of limbal ischemia should be noted. Phenylephrine should be avoided for dilation, as it can worsen limbal vasoconstriction.

Classification systems for chemical injuries have included the Roper-Hall classification3 and the newer Dua classification.4 Both systems use the epithelial defect size and the clock hours of limbal ischemia to predict visual potential in chemical injuries. The major difference between the classifications is that the Dua system subdivides the most severe chemical injuries (Roper-Hall class IV) into more categories (Dua class IV-VI) which allows for finer prognostication. For example, a Dua class IV patient with seven clock hours of limbal ischemia will likely fare better than a Dua class VI patient with 12 clock hours of limbal ischemia, but these patients would both be Roper-Hall class IV.

Treatment of ocular surface chemical injury ranges from simple for mild injuries to complex for severe ones. Sutured amniotic membrane has shown promise in moderate burns, with better visual outcomes and improved epithelialization by 21 days with nonsignificant trends towards decreased corneal neovascularization and symblepharon formation in one study.5 However, there was no significant improvement in severe burns in that study, and only one of the eyes studied re-epithelialized within 21 days. Another study showed that eyes which received sutured amniotic membrane within six days after injury fared better than those that received amniotic membrane later than six days.6 However, no eye with a Grade VI injury attained better than 20/400 vision, even with amniotic membrane therapy. Recent case studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of using sutureless amniotic membrane (e.g., ProKera) early in cases of severe chemical injury to promote re-epithelialization and minimize complications.7,8

When faced with a patient with severe LSCD from an ocular surface burn, there are several options for limbal stem cell transplant.9-11 In patients with unilateral injuries, conjunctival limbal autograft can be performed; this borrows several clock hours of healthy limbus from the patient’s fellow eye. Cultivated limbal epithelial transplant uses less tissue but requires culture of the patient’s limbal stem cells prior to implantation, which requires time and technical proficiency. Living-related conjunctival limbal allograft is an option for patients without healthy limbal tissue who have relatives willing to donate limbal tissue; keratolimbal (cadaveric) allograft is another transplant option with higher risk of rejection.

A newer procedure for patients with unilateral disease, simple limbal epithelial transplant, requires less limbal autograft tissue but doesn’t require the culture of patient’s stem cells prior to implantation.12,13 Instead, the piece of limbus is cut into small pieces that are arranged outside the visual axis in the affected eye and secured with fibrin glue on top of an amniotic membrane. Early case reports have demonstrated good re-epithelialization of the surface with good long-term results in restoring corneal epithelium in a single surgery with minimal donor tissue. This may prove to be a good option for patients with limited healthy limbal tissue and where donors and culture of limbal tissue are unavailable.

In summary, in this case we describe a young man with severe (Dua Class VI) alkali chemical injury resulting in severe LCSD. Even though these are challenging cases requiring prolonged follow-up with guarded expectations for recovery, there are several options for the treatment of significant LCSD that can be considered based on individual patient characteristics. REVIEW

1. White ML, et al. Incidence of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and chemical burns to the eye. Cornea 2015;34:1527–33.

2. Al-Moujahed A, Chodosh J. Outcomes of an algorithmic approach to treating mild ocular alkali burns. JAMA Ophthalmology 2015;133:10:1214–16.

3. Daniel J, Bunker L, et al. Alkali-related ocular burns: A case series and review. Journal of Burn Care & Research: Official Publication of the American Burn Association 2014;35:3:261–68.

4. Dua HS, King AJ, Joseph A. A new classification of ocular surface burns. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2001;85:11:1379–83.

5. Tandon R, et al. Amniotic membrane transplantation as an adjunct to medical therapy in acute ocular burns. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:2:199–204.

6. Westekemper H, et al. Clinical outcomes of amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of acute ocular chemical injury. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:2:103–7.

7. Kheirkhah A, Johnson D, Paranjpe D, et al.Temporary sutureless amniotic membrane patch for acute alkaline burns. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:8:1059–66.

8. Suri K, Kosker M, Raber IM, et al. Sutureless amniotic membrane ProKera for ocular surface disorders: Short-term results. Eye & Contact Lens 2013;39:5:341–47.

9. Haagdorens M, Van Acker SI, Van Gerwen V, et al. Limbal stem cell deficiency: Current treatment options and emerging therapies. Stem Cells International 2016: Article ID 9798374.

10. Liang L, Sheha H, Li J, Tseng SCG. Limbal stem cell transplantation: New progresses and challenges. Eye 2009;23:10:1946.

11. Atallah MR, Palioura S, Perez VL, et al. Limbal stem cell transplantation: Current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol 2016; 10:593–602.

12. Mittal V, Jain R, Mittal R, et al. Successful management of severe unilateral chemical burns in children using simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET). Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:8:1102–8.

13. Basu S, Sureka SP, Shanbhag S, et al. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation: Long-term clinical outcomes in 125 cases of unilateral chronic ocular surface burns. Ophthalmology 2016;123:5:1000–1010.