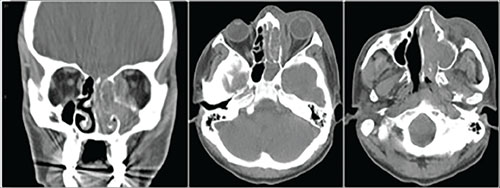

Given the concern for an evolving orbital process, computed tomography of the midface and orbits was obtained with and without contrast. Imaging disclosed complete opacification of the left nasal cavity, left frontal sinus, left maxillary sinus, left ethmoid sinuses and left sphenoid sinus, with partial opacification of the right frontal sinus and mucosal thickening of the right maxillary sinus. Preseptal soft tissue swelling was noted, as was an opacified collection within the left orbit adjacent to the lamina papyracea, concerning for a subperiosteal abscess (Figure 3). Possible bone erosion of the left medial orbit and skull base was evident. Clinical management for orbital cellulitis with subperiosteal abscess formation was initiated.

|

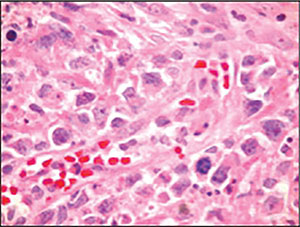

| Figure 4: Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrating a large cell neoplasm with a high mitotic index in tumor cells with prominent nucleoli. |

Cytology revealed a large cell neoplasm demonstrating a high mitotic index in tumor cells with prominent nucleoli (Figure 4). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD2, cytoplasmic CD3, CD30, CD45 and CD56, and negative for CD4, CD5, CD20, S100 and AE1/AE3. The clinical presentation and immunohistochemical profiling strongly favored a diagnosis of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKTL) of nasal type.

|

| Figure 3: Maxillofacial CT without contrast (soft tissue windows). One coronal and two axial sections demonstrate extensive nasal/sinus cavity disease with complete opacification of left ethmoid, sphenoid and maxillary sinuses, as well as subperiosteal opacification abutting the medial rectus, concerning for left orbital subperiosteal abscess. Note the possible bone erosion on the left. |

The patient underwent systemic staging, including bone marrow biopsy, which was negative; he was diagnosed with Stage IE disease. Under the care of medical oncology and radiation oncology the patient was started on concurrent cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine and prednisone chemotherapy as well as external beam radiation therapy to both orbits, the sinonasal cavities and the skull base. He has undergone annual medical oncology follow-up with positron emission tomography scans yearly for surveillance. He was noted to be disease free at his 11-year follow up.

Discussion

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, is a non-Hodgkin lymphoma composed of malignant natural killer cells in a majority of cases; however, a cytotoxic T-cell phenotype is also observed, leading the World Health Organization to reclassify the terminology in 2008.1 These malignancies typically involve the nasal cavity and or paranasal sinuses, with intraorbital involvement being less common and invariably secondary spread from adjacent sinonasal disease.1,2 Synonymous terms appearing in the literature include lethal midline granuloma, angiocentric T-cell lymphoma, malignant midline reticulosis, polymorphic reticulosis and angiocentric immunoproliferative lesion.1,3 The latter terms describe the characteristic vascular damage and prominent necrosis typically observed with histological analysis, with a resemblance to that seen in GPA. NKTL is more prevalent in Asians, as well as the Native American populations of Mexico, Central America and South America, and is more common in males than females.1,2,4 While little is known about its etiology, there is a strong association with the Epstein-Barr Virus, almost always subtype A, regardless of ethnic origin, suggesting a probable pathogenic role of the virus.5,6 In nearly all cases, neoplastic cells harbor clonal episomal EBV, and disease activity and prognosis have been shown to correlate with circulating EBV DNA titers.1,6,7

Clinically, patients may present with nasal obstruction or congestion, as in this case, or with extensive midfacial destruction. NKTL may spread to adjacent structures, including the orbit, and the rapid growth and necrosis result in an inflammatory response in surrounding tissue, often making clinical distinction from orbital cellulitis challenging.3,4,8 The mainstays of treatment have relied heavily on high-dose EBRT and chemotherapeutic regimens, with further studies needed to confirm the efficacy of various combinations.5 Of note, in contrast to other lymphomas, at present no monoclonal antibody (biologic) therapy is available for NKTL. Prognosis was generally extremely poor in the past (hence the term lethal midline granuloma). However, prognosis is now variable, largely depending on initial stage at presentation, with five-year overall survival ranging from 42 percent to 64 percent in four recent studies.7 It is likely that our patient’s successful long-term survival was due to the combination of Stage IE disease and aggressive clinical management. REVIEW

The author would like to acknowledge Jurij Bilyk, MD, for his contributions and editing of this case report.

1. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008.

2. Woog JJ, Kim YD, Yeatts RP, et al. Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma with ocular and adnexal involvement. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1:140-7.

3. Salam A, Saldana M, Zaman N, et. al. Orbital cellulitis or lymphoma? A diagnostic challenge. J Laryn & Otol 2005;119:740–742

4. Charton J, Witherspoon SR, Itani K, et. al. Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma masquerading as orbital cellulitis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;24:2:143-5.

5. Au WY. Current management of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Oncology 2010;24:4:352-358

6. Zhang Y, Ohyashiki JH, Takaku T, et.al. Transcriptional profiling of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genes and host cellular genes in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma and chronic active EBV infection. Br J Cancer 2006;94:4:599–608.

7. Huang Y, de Reynies A, de Leval L, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies emerging oncogenic pathways operating in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Blood. 2010;115:1226–1237.

8. Pine RR, Clark JD, Sokol JA. CD56 Negative Extranodal NK/T-cell Lymphoma of the Orbit Mimicking Orbital Cellulitis. Orbit 2013;32:1:45–48.