|

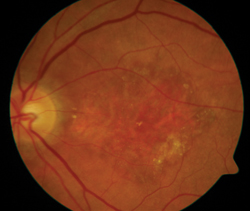

As ophthalmologists and researchers have learned more about the

process behind diseases such as dry and wet age-related macular

degeneration, they’ve been able to devise more specific treatments that

target certain contributors to those diseases, such as vascular

endothelial growth factor and inflammation. In addition, scientists have

also been hard at work on entirely new treatment approaches to AMD and

other retinal diseases, such as encapsulated cell technology and gene

therapy. Here’s a look at the latest trends in retinal research.

Phoenix surgeon Pravin Dugel says there are a few caveats with MAHALO, though. “First, it was a post-hoc analysis,” he says. “In other words it was an analysis that was done after the study was completed. Second, this was demonstrated with a monthly injection. A legitimate question is: Are patients with geographic atrophy going to be willing to get a monthly injection when the end result may not be obvious to the patient, since you’re trying to prevent visual loss rather than show improvement? Third, how many patients will be eligible for this treatment? It turns out this complement factor was present in about 57 percent of the patients in the study. So, it’s not a small minority, but instead is a bit more than half. Obviously, all this data will have to be confirmed in a larger, Phase III study, which is currently being organized.”

Another approach to dry AMD is visual cycle modulation, which is an attempt to alter the basic way rods and cones operate in an effort to decrease how much metabolic waste they produce, which researchers say represents the drusen that are the hallmark of dry AMD. “One of the strategies to decrease this metabolism is being undertaken by Acucela with its product emixustat in a Phase II/III study,” Dr. Dugel says. “This treatment is exciting because the delivery system is a pill that’s taken b.i.d. Therefore, the delivery method is very attractive.”

Dr. Garg says emixustat’s Phase II data was “very encouraging in terms of slowing down disease progression.” He says some observers will be interested to see the over-all effect on the visual cycle. “The attractive thing is it’s a pill that patients can take at home,” he says. “The potential drawback is if the rods and cones aren’t firing as often, perhaps patients won’t see very well in dim illumination.”

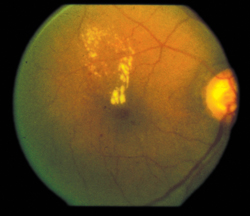

• Wet AMD treatment. In the clinical trial realm of wet AMD treatments, the agent that most are watching is the anti-pigment-derived growth factor Fovista from Ophthotec. PDGF has become an inviting target for blocking because it’s been implicated in vessel remodeling, including the kind that occurs in wet AMD. “Ophthotec completed a large Phase II study of Fovista, the largest Phase II study ever done in retina, and the results were very encouraging,” says Dr. Dugel. “It showed that the combination of the drug, when used in conjunction with Lucentis vs. Lucentis alone, resulted in a 62 percent greater improvement in visual acuity.

Second, those patients who received the combination had a regression, or shrinkage, of the neovascular membrane. Fluorescein angiography showed that the combination treatment caused regression of the neovascular membrane. On OCT, when we looked at the subretinal hyper-reflective material— which is felt to represent the lesion and lesion components—this also disappeared more commonly in the combination group. Perhaps what’s most remarkable is, when we looked at patients who lost vision, those patients who lost vision and had Lucentis monotherapy tended to fibrose and have a large disciform scar, while those patients who lost vision—and there weren’t many—and had combination therapy had very little, if any, fibrosis.

|

"Another approach to dry AMD is visual-cycle modulation, which is an attempt to alter the basic way rods and cones operate in an effort to decrease how much metabolic waste they produce, which researchers say represents the drusen that's the hallmark of dry AMD."

|

“So, I think the combination of Lucentis and Fovista has the potential to address two of the most important components of exudative AMD by having an anti-permeability effect early and an antifibrotic effect over the course of disease,” Dr. Dugel adds.

One avenue of AMD treatment that’s interesting doesn’t involve the drug, but how drugs might get into the eye, and comes from a Rhode Island company called Neurotech.

“It’s encapsulated-cell technology that acts as a sustained-delivery device,” explains Philip Rosenfeld, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. “The makers transfect RPE cells and place them in a cartridge, which is implanted in the pars plana much like the Retisert was implanted. The cells then produce certain drugs, such as anti-VEGF and anti-PDGF. If you want to stop the production, you take out the cartridge. We did a study in geographic atrophy a couple of years ago in which this device was implanted in the eye, and it sat there for two years cranking out this desired protein, and current clinical trial results from Mexico also look good.”

• Diabetic macular edema treatment. Regeneron’s Eylea, which originally entered the ophthalmology world as a treatment for wet AMD, also recently posted results in a trial for the treatment of diabetic macular edema, and surgeons tentatively say it looks like a viable option. “In the Phase III trial of Eylea for DME, roughly 45 percent of the patients got at least two lines of improvement, and around 40 percent got three lines or better,” says Dr. Garg. “The results are impressive, and comparable to the Lucentis results for DME. This situation that’s now arisen is similar to what happened in AMD: You’ve got a drug like Lucentis, which is a great drug. Now you have another drug, which is similar, become available. Sometimes, certain drugs seem to work better for certain patients. What’s interesting, and what we don’t know about Eylea for DME, is we don’t know if we can dose it differently than Lucentis or not, or if it will last longer or allow patients to not have to get as many injections. With wet AMD, of course, that’s what the VIEW trials were about. In VIEW, patients would get three monthly injections of Eylea initially and then an injection every other month. The researchers found every-other-month injections, on average, worked as well as monthly injections seemed to work with Lucentis. But, in the DME trial of Eylea, we don’t know if that’s true or not. Any potential advantages to the different drug, though, have yet to be determined.”

|

Dr. Dugel says a sustained-release option might be ideal for certain patients. “We know that anti-VEGF, though effective, when given on monthly basis is difficult to sustain,” he says. “We also know that there are some patients in whom inflammation is a factor, as well as some patients in whom anti-VEGF monotherapy isn’t sufficient. So, the most exciting thing for DME would be the ability to use sustained-release delivery devices.” In addition to Ozurdex, in the future, surgeons believe we may yet see the Iluvien implant (which releases fluocinolone), which was denied FDA approval, return. “I don’t think the company is giving up, and I think the FDA is still receptive to the conversation,” says Dr. Garg. (For an update on Iluvien’s FDA review, please see Review News, p. 9.)

Dr. Dugel thinks having both Ozurdex and Iluvien approved would give ophthalmologists the most flexibility in treatment, since they’re similar but different. “It’s important to understand that these devices aren’t the same,” Dr. Dugel explains.

“The elution rates are different. For instance, with Ozurdex you get a burst pattern in which there’s an initial increase of the steroid, dexamethasone, and then a gradual decline in the release. And, afterward, the material is entirely biodegradable. With Iluvien, you get near zero-order kinetics and it lasts for up to three years. Its material isn’t biodegradable, though, because it’s surrounded by an inert casing, with only the tips exposed.”

“The reason these devices are exciting is that although we have patients in whom anti-VEGF therapy with or without laser may be sufficient,” says Dr. Dugel, “we also have patients who have an unmet need in whom it’s not sufficient. In those patients, we may be able to give Ozurdex first, maybe a few times, and that may be sufficient. Yet we also have patients with very severe disease where even that is not sufficient, and in such severe patients we may be able to give Iluvien that will last for three years. Hopefully, these steroid delivery devices will be approved very soon because we desperately need combination treatment options in different phases and severities of DME.”

• Gene therapy. Gene therapy is a broad term that can mean implanting viral vectors that carry genes that code for the release of an anti-VEGF protein to implanting a viral vector that insinuates itself into a faulty part of the eye’s genetic code and fundamentally changes the DNA so that it works properly again.

Two companies, Avalanche (Sydney, Australia) and Genzyme (Cambridge, Mass.), are studying the former approach, using a gene to release therapeutic proteins in the eye. Boston retinal specialist Jeffrey Heier, director of the vitreoretinal service at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston, and a scientific advisor for Genyzme, says, “First, we think gene therapy is very well-suited to the eye because in the eye there are diseases that have been well– studied, tissues that are accessible—either by intravitreal or subretinal delivery—and you have ways of studying the outcomes. In other words, you can monitor the out-come with technology such as fundus photography or OCT. These characteristics make the eye a nice target for gene therapy.

“Next is the concept that so many of the advances we’ve seen in the past decade require intravitreal injections,” Dr. Heier continues. “While the safety and efficacy of these has been quite good, there’s still a treatment burden to these injections, especially when the injections, or the monitoring, are required so frequently. Gene therapy offers the potential to be able to achieve this with a single injection that lasts for a prolonged period of time. The concept of treating these eyes that require multiple anti-VEGF injections with gene therapy instead is very enticing.”

Dr. Heier says the process is yielding positive results so far. “You take a gene that codes for a protein, such as an anti-VEGF protein (both Genzyme and Avalanche use sFLT01, a soluble VEGF receptor), and combine that with AAV2—adeno-associated virus,” Dr. Heier explains.

“AAV2 has been studied in numerous trials—around 20 to date, I believe—for many different diseases, and its safety profile is encouraging. You combine the two and inject the gene therapy product, and the gene is expressed in certain cells and these cells, in essence, produce the anti-VEGF protein.”

|

"The reason sustained-delivery steroid devices for diabetic macular edema are exciting is that although we have patients in whom anti-VEGF therapy with or without laser may be sufficient, we also have patients who have an unmet need in whom anti-VEGF therapy is not sufficient."

–Pravin Dugel, MD |

He says that different routes of administration of the gene therapy product offer different benefits. “One approach, which is used by Genzyme, is the intravitreal approach, which has certain advantages,” says Dr. Heier. “The other is the subretinal approach, employed by Avalanche, that offers different advantages. The advantage of an intravitreal approach would be ease of administration—it’s a technique that we all do multiple times each day. The potential disadvantage is the need to get adequate expression to the tissues you want, and it’s been hypothesized that the ILM may prevent adequate uptake or expression from the gene therapy product in areas other than the macula and the peripheral retina.

“The subretinal approach requires a surgical procedure, but is one that many of us do already,” Dr. Heier adds. “The procedure is similar to what we use for injecting tPA subretinally in patients with large submacular hemorrhages. So the advantage there is you know you’re getting the gene therapy product to the cells that you’re interested in having express it. But the disadvantage is you’re doing a surgical procedure, albeit one that we use frequently and appears relatively safe.”

Avalanche is conducting a Phase I/II study, and Genzyme is doing a Phase I currently. “Avalanche has presented its initial work, and it’s encouraging,” Dr. Heier says. “They’ve shown relative safety and nice anatomic outcomes in some patients. Their full data is going to be presented at the meetings in the fall. Genzyme hasn’t released their results to date, but is expected to do so in the late fall. Both approaches have had preclinical work in animals that has shown a prolonged effect over time.”

For rarer retinal degenerative conditions such as Leber’s congenital amaurosis, experts say some of the most exciting work is being done by University of Pennsylvania researcher Jean Bennett, MD, PhD, which also incorporates an adenoviral vector in its mechanism. “The virus, carrying protein complementary DNA, is designed to incorporate itself into the RPE and fundamentally change the RPE’s DNA, causing it to express proteins correctly,” says Dr. Garg. “This enables the patients to have vision again. It is fixing what is wrong with the gene. In other areas of gene therapy, we know that we can map a genetic defect and, for some diseases, pinpoint it with a high degree of accuracy, but then we run into trouble when we try to do something about it—to replace it, if you will. Dr. Bennett’s work is actually taking the virus and incorporating it into the patient’s defective DNA, allowing the natural human cells to start making the correct protein.”

Dr. Dugel says one of the most exciting aspects of retinal research is the potential for crossover between diseases. “There’s a lot of bio-physiologic commonality between exudative AMD, vein occlusion and DME,” he says. “So, if any of these treatments succeed in neovascular AMD, I’ve no doubt we’ll be seeing the same strategy taken up in vein occlusion and DME, as well.”

REVIEW