Surgeons say that dry-eye disease after LASIK is one of the most miserable complications patients can experience, and managing it often involves a lot of patient stress, hand-holding, chair time and sheer recovery time. In light of this, surgeons say that when a patient with dry eyes comes into their office requesting laser vision correction, they have their work cut out for them, since they don’t want to make a moderate condition bad or a bad condition worse. Here, experienced refractive surgeons weigh in on their approach to these patients.

Assessing the Dry Eye

Since the postop stakes are high if a patient develops bad dry eye, surgeons make sure to root out any preop dry eye and its cause.

“There’s not one test that gives you the answer, but instead it’s a variety of factors that you put together,” says Christopher Rapuano, MD, Wills Eye Institute cornea and external disease director. “If I had to pick one, though, it would be determining how symptomatic they are from dry eye. Many people who get laser vision correction were contact lens wearers for many years and did fine. Then, their eyes got a little on the dry side and they couldn’t comfortably wear their contacts anymore because their eyes got red and irritated. So, they stopped wearing contact lenses and came to see you about refractive surgery. You have to ask these patients why they stopped wearing contacts. If they say that they just didn’t like to put them in anymore, or they got an infection and became too scared to keep wearing them, that’s one thing. But if they say their eyes were bone dry and irritated when they put their contacts in, that’s a clue that they’ve got some dryness issues and they’re at higher risk. And this is a reasonable number of patients.

“For those higher-risk patients, I’ll go more in-depth with my tests,” Dr. Rapuano continues. “This includes performing tests like lissamine green staining and Schirmer’s, which I don’t do on everyone.”

Teaneck, N.J., corneal specialist Peter Hersh also tries to discriminate between patients who are just contact lens-intolerant and those with physiologic dry eye, and then relies on a thorough exam. “More often than not, the dry eye is secondary to blepharitis or inflammation secondary to blepharitis,” he says. “So I’ll check to see whether the patient has lid margin changes or inspissation of the meibomian glands. I’ll evert the lids to see if there’s a follicular reaction, especially to contact lenses. Then I turn to the conjunctiva and cornea. I first evaluate the tear film, the tear-film breakup time—which we do in all patients—and certainly look for any staining with fluorescein. Questions I consider are: Is there any superficial punctate keratitis? If there is, is it localized? Is it more of an inferior thing that might be secondary to a blepharitis? I can use the last question in my blepharitis analysis, as well. Often, the SPK will be inferior and associated with blepharitis.”

The staining pattern, both initially and on follow-up after some dry-eye treatment, can be very helpful when deciding if someone is a candidate for LVC. “If there’s pan-SPK and staining of the conjunctiva, that’s a real red flag that the patient has a real dry-eye pathology,” avers Dr. Hersh. “Those are the kinds of patients we might not be able to treat and get in good-enough shape to proceed with LVC.”

Rehabilitating the Eye

After they’ve assessed the patient’s dry eye, physicians then embark on a course of treatment and will follow-up with the patient to see if it’s made a difference in the disease.

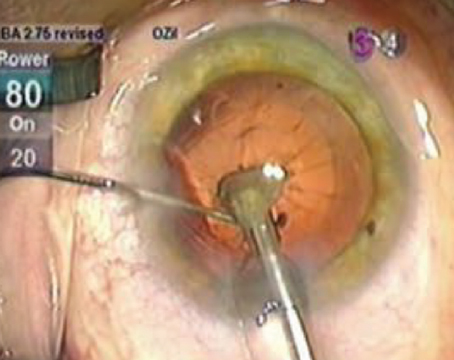

Sadeer Hannush, MD, attending surgeon on the cornea service at Wills Eye Institute and assistant professor of ophthalmology at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, says that for patients who are simply dry, he’ll “prepare them by inserting a plug in their inferior punctum and possibly putting them on Restasis twice daily a few weeks before surgery.” However, he’ll treat more involved conditions in different ways. “There are various ways of managing lacrimal deficiency: tear supplementation; punctal occlusion; reinvigorating the lacrimal gland with anti-inflammatory agents such as loteprednol or cyclosporine,” he says. “On the other hand, in the case of evaporative dry eye due to meibomian gland dysfunction, which causes inflammation of the lid margins and prevents oil from covering the tear film, the treatment historically has been lid hygiene, warm compresses, oral doxycycline and the occasional use of anti-inflammatories. There are also new techniques, such as azithromycin drops, which work through a different mechanism in rehabilitating the lid margins, or the LipiFlow device that drains the meibomian glands and opens the pores, creating a healthy surface for a period of time.” Dr. Hersh will also consider adding omega-3 fatty acid supplements to the blepharitis treatment.

For the patients who need such treatment before LVC, as opposed to those who are just a little dry, Dr. Rapuano will check back with them one to three months after initiating the treatment. “After a month or so, I’ll perform some staining again and may do Schirmer’s,” he says. “The amount of observed staining is important. If they have significant staining—and dry eye tends to be in the middle to lower third of the cornea—and it looks like there’s still dry eye, then we won’t perform LVC on them. I tell them that, if their corneal and conjunctival surfaces are normal, I’ll do refractive surgery on them. If it’s never normal, then I’ll never do surgery on them.”

LASIK or Surface Ablation?

Because lamellar procedures sever corneal nerves while surface ablations leave them intact, some surgeons feel that, in borderline cases, surface ablation might be preferable. Surgeons are quick to add that this is more of a clinical impression than one supported by the literature.

|

Some surgeons argue that LASIK can be made more gentle on the corneal nerves by using a nasal hinge, since the nerve plexus is denser nasally and temporally than it is superiorly or inferiorly. “My position, however,” says Dr. Hannush, “is if a patient has dry eye—and is my mother or sister—I’d opt to preserve the entire nerve plexus and just do a surface procedure.” Dr. Rapuano says a thinner flap might also be better for the same reasons, since it cuts fewer corneal nerves.

Dr. Hersh says, though, that he’s not sure there’s a difference. “In some cases, I’m more concerned that dryness will influence the quality of the epithelial healing after PRK than I am that the LASIK flap will exacerbate the dryness,” he says.

Dr. Rapuano says that, whichever procedure is chosen for patients who are deemed suitable, there will be those who still have dry-eye problems postop, and need your attention. “In the case of any patient with complications, surgeons tend to not want to see them and be reminded that some patients are unhappy,” he says. “It’s a natural reaction, really, but surgeons need to overcome it and overcompensate for it. They need to see these patients more frequently if they want to be seen, and schedule them for the beginning or end of the day when the physician has more time for them and isn’t rushed. Patients want to know that you’re trying to help them, whether you did the surgery or someone else did. Tell them that you understand that they’ve got dry eye, you’re doing your best to help them and that, fortunately, it usually gets better over three, six or 12 months.” REVIEW

1. Murakami Y, Manche EE. Prospective, randomized comparison of self-reported postoperative dry eye and visual fluctuation in LASIK and photorefractive keratectomy. Ophthalmology 2012;119:11:2220-4.