Inflammatory chorioretinopathies of unknown etiology, also called "white dot syndromes" are common uveitic entities that affect relatively young, otherwise healthy, patients. These entities include: acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy; multiple evanescent white dot syndrome; serpiginous choroiditis; birdshot chorioretinopathy; subretinal fibrosis and uveitis; multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis; punctate inner choroidopathy; acute zonal occult outer retinopathy and, more recently, relentless placoid chorioretinitis; acute macular neuroretinopathy; acute retinal pigment epitheliitis; unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy; unifocal helioid choroiditis; and persistent placoid maculopathy.

These diseases primarily affect the posterior uveal tract and may present with white inflammatory lesions in retina, pigment epithelium, and/or choroid. Some of these conditions, like APMPPE, have a self-limited course and have an extremely good visual prognosis with preservation of central vision. Others, such as subretinal fibrosis and uveitis syndrome, can have a relentless and progressive course, require treatment with corticosteroids and other corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory agents, and can lead to blindness. Viral infections have been associated with many of these conditions, but only acute idiopathic maculopathy has been shown to be associated with Coxsackie virus responsible for hand, foot and mouth disease.1 These entities otherwise have no identifiable cause. In the future, these entities may be proven to be autoimmune or infectious or both. It is also thought that these entities may represent different phenotypic disease manifestations of a single agent, differing in appearance only because of the underlying genotype of the individual affected.

Many of these conditions may be associated with serious retinal or choroidal sequelae, such as choroidal neovascularization or macular scars that could result in delayed visual loss even after the original disease process has become inactive. The more common entities will be discussed in detail, and the rare entities, often described in only one or two peer-reviewed publications, will be presented. This first installment of the series will discuss acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, multiple evanescent white dot syndrome and serpiginous choroiditis.

APMPPE

Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epithliopathy is a bilateral inflammatory disease affecting the retinal pigment epithelium and outer retina in otherwise healthy young adults.2-12 It is usually preceded by a viral prodrome that may be associated with meningeal symptoms.2 Subsequently, patients develop sudden onset of bilateral visual symptoms. Ocular examination reveals a quiet anterior chamber and very few vitreous cells. Multiple yellow- to cream-colored, sometimes confluent, placoid lesions of variable size at the level of the outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium and choriocapillaris are present in both eyes (See Figures 1a & b).2 Exudative retinal detachment, disc hyperemia and episcleritis may occur.8 Fatal cerebral vasculitis has rarely been associated with APMPPE.5 Systemic corticosteroids are required to treat such patients.

The diagnosis is usually made by clinical appearance and characteristic fluorescein angiographic findings. Fluorescein angiogram demonstrates early hypofluorescence with late hyperfluorescent staining of the placoid lesions (See Figures 2a & b).2 Indocyanine green angiography also shows hypofluorescent spots corresponding to the placoid lesions.

Differential diagnosis includes metastatic tumors, viral retinitis, toxoplasma retinochoroiditis and pneumocystis choroiditis.

Adenovirus type 5 infection has been serologically documented in patients with APMPPE.10 Histopathology of patients with APMPPE has not been studied. It is thought that the lesions occur at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium or the choriocapillaris.2 Numerous other systemic associations have been described with APMPPE including meningoencephalitis,5 nephritis9 and hearing loss.3

APMPPE resolves spontaneously in two to 12 weeks and does not usually require treatment.2,11 In some cases, systemic corticosteroids may speed resolution of the placoid lesions and/or serous detachment.

Most patients with APMPPE have a self-limited course with resolution of lesions in two to six weeks.2,4,11 Visual acuity is diminished very profoundly in the early phases of the disease in some cases but recovers nearly completely to near normal levels within two to three weeks of onset of symptoms. Some patients may have difficulty with reading due to persistent scotomas in the central field. Pigmentary alterations may remain after the resolution of the placoid lesions. There are rare cases of chronic persistence or recurrent APMPPE, and recurrent cases may appear so similar to serpiginous choroiditis that they have been labeled "ampiginous choroiditis." Chronic, recurrent cases probably represent relentless placoid chorioretinitis.13 Rarely, choroidal neovascularization may develop as a complication of APMPPE.

MEWDS

Multiple Evanescent White Dot Syndrome is a unilateral inflammatory chorioretinopathy that predominantly affects young, healthy women in the second to fourth decades of life.14,15 One half of patients may have a viral prodrome prior to disease onset.14

Patients who have MEWDS typically have unilateral, acute painless vision loss. The patients may have a temporal paracentral scotoma corresponding to an enlarged physiologic blind spot, associated with shimmering photopsias in the temporal visual field.14-16 Ocular findings may include a variable amount of vitreous inflammation, optic disc edema and characteristic multiple white spots at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium or deep retina in the posterior pole. These spots are generally between 10 and 100 µm in size. They are numerous and scattered throughout the posterior pole (See Figures 3a & b). The fovea has a characteristic granular appearance in the acute phase of the disease (See Figure 3c).14-16 Even after resolution of the disease, the fovea does not return to normal appearance. A small minority of patients may have chronic MEWDS and may develop choroidal scarring.

Diagnosis is made by typical ocular findings. Visual field testing may reveal an enlarged blind spot.14,16 Fluorescein angiography often reveals punctate staining of the pigment epithelium in the posterior pole and disc leakage. The punctate staining is sometimes in the shape of a wreath.14,16 ICG angiography shows multiple hypofluorescent areas in the posterior pole.17 Reduction of a-wave amplitude on the electroretinogram may occur in the acute phases of the disease.18 This returns to normal after resolution of the disease process.

Differential diagnoses includes APMPEE, acute macular neuroretinopathy, multifocal choroiditis panuveitis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy, diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, primary intraocular lymphoma and sarcoidosis. It is felt that idiopathic blind spot enlargement, MEWDS and MCP may represent a spectrum of the same disease process.19-21

MEWDS has a self-limited course, and no specific treatment is required. The white dots and disc edema fade within two to six weeks; however, visual symptoms such as the enlargement of blind spot, temporal scotoma, and photopsias may take several months to resolve. Recurrence is uncommon but has been reported in 10 to 15 percent of patients.15,22 Prognosis for patients with recurrences is also excellent.22 Choroidal neovascularization is a rare late complication of MEWDS.23

Serpiginous Choroiditis

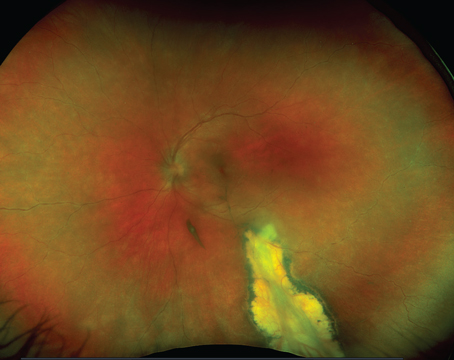

Serpiginous choroiditis has been described under different names including geographic helicoid choroidopathy.24,25 It is a choroidal inflammatory disease that typically affects healthy patients in the second to seventh decades of life.24 Patients who have serpiginous choroiditis typically have painless onset of paracentral scotoma and vision loss. There is asymmetric involvement but eventually the disease does become bilateral over time.24-26 On examination there may be some inflammatory response in the anterior chamber27 or the vitreous, but this is variable and minimal. Chorioretinal lesions are grey-white and associated with retinal and RPE edema when active (See Figure 4). Lesions typically start in the peripapillary region and move in a serpiginous or snake-like fashion around the posterior pole and progress to involve the macula gradually over time (See Figure 4). The disease process has a step-wise, progressive course. Typical new lesions of serpiginous choroiditis appear contiguous to old atrophic ones.24-26 A macular variant of serpiginous choroiditis has also been described with active lesions initially occurring in the macula without peripapillary involvement.28 Subretinal hemorrhage and subretinal fluid is characteristic of choroidal neovascularization that complicates up to one-third of patients with serpiginous choroiditis.29

Diagnosis is based on typical clinical appearance and fluorescein angiography.

Fluorescein angiography demonstrates early hypofluorescence and late hyperfluorescence of active lesions.24-26 Laboratory evaluation is unrevealing. In the original descriptions of serpiginous choroiditis, most patients had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis or were purified protein derivative skin test positive;26 however, treatment with antituberculous agents does not impact the course of serpiginous choroiditis.26,30

Tuberculous choroiditis can indeed look identical to serpiginous choroiditis.30

Differential diagnosis includes tuberculous choroiditis, APMPPE, relentless placoid chorioretinitis, multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis, birdshot retinochoroidopathy and ocular histoplasmosis syndrome.

The pathology of serpiginous choroiditis reveals extensive loss of retinal pigment epithelium with destruction of the overlying retina and lymphocytic infiltration of the choriocapillaris and choroid.31

The treatment of serpiginous choroiditis can be complex. Macula-threatening lesions can result in profound vision loss. Systemic, paraocular and even intraocular corticosteroids may be utilized in the treatment of active lesions.31-33 Intraocular triamcinolone may be particularly effective in treatment of fovea-threatening lesions when rapid reduction of choroidal inflammation is necessary.33 Chronic long-term remissions have been achieved only with the use of alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil often in combination with other immunosuppressive medications.32 Choroidal neovascularization can be treated with focal laser photocoagulation,29 photodynamic therapy or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor.

Serpiginous choroiditis has a relentless course in many cases, with eventual foveal destruction. Central vision is lost in more than 20 percent of cases and this can occur as result of direct involvement of the fovea by inflammatory lesions or the development of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization.24-26,30

In the July issue, this article will conclude with a review of birdshot chorioretinopathy; subretinal fibrosis and uveitis; multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis; punctate inner choroidopathy; acute zonal occult outer retinopathy and, more recently, relentless placoid chorioretinitis; acute macular neuroretinopathy; acute retinal pigment epitheliitis; unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy; unifocal helioid choroiditis; and persistent placoid maculopathy. For a printable table of these and all of the conditions described, visit http://www.revophth.com/email/0609_table/0609_ret_table.pdf.

Dr. Moorthy is an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology and director of the Uveitis Service at

1. Beck AP, Jampol LM, Glasser DA, Pollack JS. Is Coxsackievirus the cause of unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy? Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:121-3.

2. Gass JDM. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1968;80:177-85.

3. Clearkin LG, Hung SO. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy associated with transient hearing loss. Trans Ophthalmol Soc

4. Holt WS, Regan ADJ, Trempe C. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1976;81:403-12.

5. Kersten DH, Lessell S, Carlow TJ. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy and late-onset meningo-encephalitis. Ophthalmology 1987;94:393-6.

6. Ryan SJ, Maumenee AE. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1972;81:1066-74.

7. Wright BE, Bird AC, Hamilton AM. Placoid pigment epitheliopathy and Harada's disease. Br J Ophthalmol 1978;62:609-21.

8. Savino PJ, Weinberg RJ, Yassin JC, Pilkerton AR. Diverse manifestations of acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1974;77:659-62.

9. Laatikainen LT, Immonen IJR. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy in connection with acute nephritis. Retina 1988;8:122-4.

10. Azar PJ, Gohd RS, Waltman D, Gitter KA. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy associated with an adenovirus type 5 infection. Am J Ophthalmol 1975;80:1003-5.

11. Damato BE, Nanjiani M, Foulds WS. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. A follow-up study. Trans Ophthalmol Soc

12. Isashiki M, Koide H, Yamashita T, Ohba N. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy associated with diffuse retinal vasculitis and late haemorrhagic macular detachment. Br J Ophthalmol 1986;70:255-9.

13. Lim WK, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Serpiginous choroiditis. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:231-44.

14. Jampol LM, Sieving PA, Pugh D, et al. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome. I. Clinical findings. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:671-4.

15. Aaberg TM, Campo RV, Joffe L. Recurrences and bilaterality in the multiple evanescent white-dot syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1985;100:29-37.

16. Mamalis N, Daily MJ. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome. A report of eight cases. Ophthalmology 1987;94:1209-12.

17. Ie D, Glaser BM, Murphy RP, et al. Indocyanine green angiography in multiple evanescent white-dot syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:7-12.

18. Sieving PA,

19. Callanan D, Gass JD. Multifocal choroiditis and choroidal neovascularization associated with the multiple evanescent white dot and acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement syndrome. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1678-85.

20. Khorram KD, Jampol LM,

21. Singh K, de Frank MP, Shults WT, Watzke RC. Acute idiopathic blind spot enlargement. A spectrum of disease. Ophthalmology 1991;98:497-502.

22. Moorthy RS, Jampol LM. Posterior Uveitis of Unknown Cause. In Ophthalmology. 2nd Ed. Ed. Yanoff M, Duker JS.

23. Wyhinny GJ, Jackson JL, Jampol LM, Caro NC. Subretinal neovascularization following multiple evanescent white-dot syndrome [letter]. Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1384-5.

24. Bock CJ, Jampol LM. Serpiginous choroiditis. In: Albert DM, Jakobiec FA, eds. Principles and practice of ophthalmology.

25.

26. Laatikainen L, Erkkila H. A follow-up study on serpiginous choroiditis. Acta Ophthalmol 1981;59:707-18.

27. Masi RJ, O'Connor GR, Kimura SJ. Anterior uveitis in geographic or serpiginous choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol 1978;86:228-32.

28. Mansour AM, Jampol LM, Packo KH,

29. Jampol LM, Orth D, Daily MJ, Rabb MF. Subretinal neovascularization with geographic (serpiginous) choroiditis. Am J Ophthalmol 1979;88:683-9.

30. Gupta V, Gupta A, Arora S, Bambery P, Dogra MR, Agarwal A. Presumed tubercular serpiginouslike choroiditis: Clinical presentations and management. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1744-1749.

31. Gass JDM. Serpiginous choroidopathy. In: Gass JDM, ed. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: Diagnosis and treatment.

33. Pathengay A. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide in serpiginous choroidopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol 2005;53:77-79.