As intraocular lenses have become more technologically advanced, the issues surrounding patient selection, lens implantation and patient management have become more complex. At the same time, the technology used to select the best lens for a given patient has improved dramatically, and doctors’ understanding of how to choose appropriate candidates and manage them before and after surgery has become far more sophisticated than it was when premium lenses first appeared.

R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Associates in Alexandria, Louisiana, and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University and Tulane Schools of Medicine in New Orleans, notes that success with these lenses has become easier. “The lenses are better now,” he says. “We still have a few postoperative issues, but not nearly the number we had in the past.”

Nevertheless, problems can still occur. “When it comes to advanced technology IOLs, several possible postoperative concerns can lead to a dissatisfied patient,” notes Elizabeth Yeu, MD, a partner at Virginia Eye Consultants in Norfolk, and an assistant professor at the Eastern Virginia Medical School. “Potential issues include objective or subjective problems related to the ocular surface, including dry eye; residual refractive error; IOL-related concerns, such as problems with night vision or quality-of-vision issues; blurred vision as a result of posterior capsular opacification; or simply unmet expectations. Essentially, our patients are our customers, and good customer service underlies everything. Leaving clinical issues unresolved will lead to dissatisfaction.”

Here, surgeons offer insights regarding how to manage problems that may arise, along with a few pearls for preoperative patient management that can help to minimize these postoperative issues.

Refractive Surprises

Although an imperfect lens power calculation is always a possibility when a postoperative refractive surprise occurs, such issues are becoming less common. (For more on how to avoid miscalculating the lens power, see “IOL Power Formulas: 10 Questions Answered” in the January 2018 issue of Review.) Other issues such as corneal problems and toric lens rotation also need to be considered.

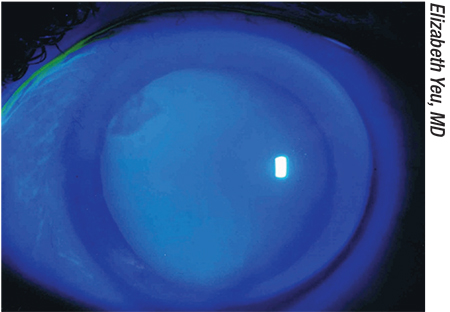

“Postoperative ocular surface issues can lead to visual difficulties, discomfort and an unhappy patient, and the number one cause of ocular surface issues is dry-eye disease,” notes Dr. Yeu. “Preoperative dry eye can lead to a refractive surprise, with undercorrected or overcorrected astigmatism or an altered spherical equivalent outcome—but postoperative exacerbation of dry-eye symptoms can also be problematic.

“Dry eye isn’t as straightforward as we used to believe,” she continues. “If you look at a study like the one conducted by Pria Gupta, MD and Chris Starr, MD,1 about three-quarters of patients coming in for cataract surgery have at least mild to moderate dry eye, but only a small number of them have actually been diagnosed with dry-eye disease. It’s a diagnosis that’s easy to miss in many patients. Many of our older patients may not feel dry, per se, or they may not have the classic symptom of irritation. They may only have a fluctuating vision issue, if the disease is mild preoperatively. But postoperatively, a subclinical or asymptomatic case of dry eye may become clinically symptomatic. The reasons are not completely straightforward, but use of medications relating to the cataract surgery is a common etiology.”

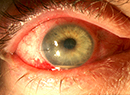

|

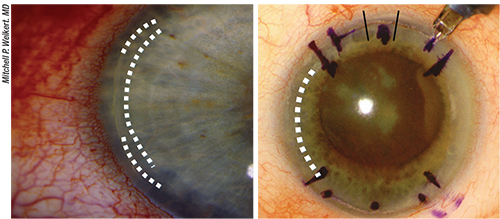

| A refractive surprise can result from subtle corneal problems missed before the surgery—or that occurred after the surgery because of the use of postoperative drops. Above: A Salzmann’s nodule at 10 o’clock. |

Adding to the complexity of the problem, a refractive surprise can also be the result of other subtle corneal problems that were missed before the surgery—or that have occurred following surgery because of the postoperative drops. These can include subtle epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, nodular degeneration or a pterygium that wasn’t addressed preoperatively. “Some patients coming in for cataract surgery have very minimal epithelial basement membrane dystrophy that may only involve the superior 10 percent of the peripheral cornea,” says Dr. Yeu. “If you lift up the lid, it’s actually relatively common to find this. But postoperatively, whether because the patient caused corneal trauma with the tip of the eye dropper or because of the toxicities of the medications, it goes from subclinical EBMD to a very clinically relevant EBMD. It may not be that the clinician missed the problem—the EBMD may simply become a much bigger issue as the surface decompensates postoperatively.

“Because this is a possibility, whenever you have an unhappy patient related to a refractive ‘miss’ leading to a sub-par visual outcome, you have to look for a few things,” she continues. “A carefully performed refraction is going to be very important, but that has to be accompanied by a very careful ocular surface examination, both before and after staining. Prior to any drop instillation, you should repeat whatever diagnostic images were obtained preoperatively, to compare them and see if there’s an interval difference that could be the source of the surprise outcome. If the problem appears to be caused by a poor ocular surface, aggressive treatment to normalize the surface will be necessary as an initial step, prior to moving forward with any other intervention. Lastly, a macular OCT should be a part of the evaluation for patients with suboptimal postoperative vision and for refractive misses.”

Residual Refractive Error

Arrdalan Eddie Aminlari, MD, who practices at The Morris Eye Group in Encinitas, California, says it’s remarkable how good refractive outcomes have become, with both monofocal and presbyopia-correcting lenses. “However, every once in a while someone will fall outside the normal range, with long or short axial lengths, or steep or flat corneas,” he notes. “It can be a little more difficult to achieve a perfect outcome with these patients, so postoperatively, refractive surprises sometimes still need to be addressed.

“There are several ways to address them,” he says. “Even very low residual astigmatism can effect near, intermediate and distance vision, and it’s important to address this in patients who receive a premium lens, which requires an excellent optical system. If the patient has a small amount of mixed astigmatism, but has a spherical equivalent of plano, I might address this with manual limbal relaxing incisions. Performing LASIK or PRK is a reasonable option for patients who have a higher level of compound or mixed astigmatism.

“Patients with higher levels of residual spherical errors might require a lens exchange, or in rare cases a piggyback IOL,” he continues. “However, it would have to be a big refractive miss for me to do a lens exchange. Again, with the new equipment and formulas we’re using today, needing a lens exchange is uncommon, even in patients with previous refractive surgery.”

Dr. Yeu agrees. “If the refractive error is small, say, on the order of 1.25 D or less, and it’s just mixed astigmatism because the spherical equivalent is relatively close to emetropia, performing astigmatic keratotomy or one or more limbal relaxing incisions could be the answer,” she says. “However, if it’s a larger refractive error, or the spherical equivalent is significantly off, then you’ll have to think about whether the patient is a candidate for a laser application like LASIK or PRK, or whether the patient would be better served by doing an IOL exchange. Ultimately, especially if it’s a quality-of-vision concern, the patient may need an IOL exchange. However, resorting to a lens exchange isn’t that common anymore, because our current advanced technology lenses produce a better overall quality of vision, with fewer of the night-vision dysphotopsia concerns that patients may complain about.”

|

| Addressing dry eye in premium lens patients, both preoperatively and postoperatively, is crucial, surgeons say. Studies suggest that three-quarters of patients coming in for cataract surgery have at least mild to moderate dry eye, but only a small number of them have actually been diagnosed.1 Above, left: One study found that 25.9 percent of cataract patients had previously received a diagnosis of dry-eye disease, but 80.9 percent had an ITF dry eye level of 2 (indicating moderate dry eye) or higher, based on the presence of signs and symptoms.3 Right: At the same time, a significant number of multifocal lens patients attribute dissatisfaction with their lenses to symptoms of dry eye.4 |

Of course, when the implanted lens is toric and the patient’s astigmatism isn’t effectively resolved, postop rotation is an obvious potential culprit. Dr. Aminlari says that he’s found two strategies that help to prevent postop toric lens rotation. “At the time of surgery, I leave the intraocular pressure a little lower than I would normally leave it,” he says. “I can check by palpation to make sure the eye isn’t overinflated, as there’s a tendency for the lens to rotate in this situation. It’s also important to remove all viscoelastic, including underneath the lens, because retained viscoelastic can also cause a lens to rotate after surgery. These strategies come into play with toric multifocals and extended-depth-of-focus torics as well.”

Dr. Aminlari adds that he uses the LENSAR femtosecond system, which has a feature that helps him should postoperative rotation occur. “The LENSAR system incorporates Intelli-Axis, which creates a capsular mark allowing the placement of the lens with a much higher degree of certainty,” he explains. “Postoperatively, if you find a residual astigmatic error on refraction, it’s easy to identify the location of the toric markers in relation to the capsular mark.

“In that situation, if I do see rotation, I don’t wait very long to go in and rotate the lens,” he adds. “I usually go in within the first few weeks.”

Managing Dysphotopsias

When implanting a presbyopia-correcting IOL, dysphotopsias such as glare and haloes are a common postoperative complaint. Dr. Yeu points out that most patients who are likely to be bothered by postoperative dysphotopsias can be identified before surgery. “When I talk to the patient preoperatively, I look to see if the patient has a high level of concern or a lot of fear tied to night-vision-related issues,” she says. “Of course, this might be an concern for someone who does commercial driving at night or works the graveyard shift. If that individual is determined to try a presbyopia-correcting lens, I’ll choose the lowest add possible, and I’d consider a mid- to low-add multifocal or an extended-depth-of-focus IOL.

“If we’re proceeding with one of these patients I’ll start by treating the nondominant eye,” she continues. “Then, if the patient has a significant problem during the postoperative period, we can stop and decide how to move forward. One option is to balance the nondominant eye with a monofocal for distance in the dominant eye. That gives the patient a kind of customized vision, where they’re able to maintain ‘social reading.’ That means that although they won’t be able to sit and read a book or work on the computer for more than 10 or 15 minutes without spectacles to support their near vision, they can at least look at their phone or read a restaurant menu without having to search for reading glasses. Meanwhile, this arrangement will mitigate their night vision problems. This approach has allowed me to avoid doing an IOL exchange in a number of patients.”

Dr. Yeu says this same strategy can work when a patient seems like a good candidate for bilateral implantation of a presbyopia-correcting IOL, but ends up unhappy with the dyspho-

topsias. “If a patient like this comes back four to six months later and the situation hasn’t gotten better, but the patient doesn’t want to lose the freedom of independence from spectacles, I’ll offer them the same option,” she says. “Doing an IOL exchange in the dominant eye, swapping out the presbyopia-correcting lens with a monofocal for distance, often saves us from having to do a bilateral IOL exchange. Patients are often happy with that compromise.”

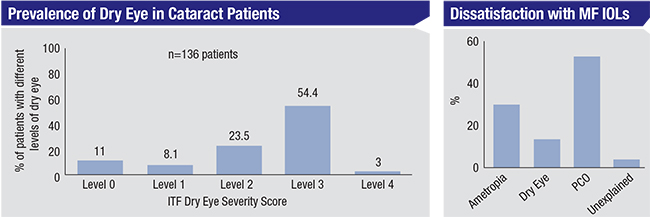

|

| An IOL that’s significantly tilted can cause a refractive problem and lead to a shift in refractive astigmatism—especially when it’s a multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus IOL. |

Postoperative Pain

Dr. Yeu notes that patient dissatisfaction is frequently associated with postoperative pain. “It’s important for us to do everything we can around the time of surgery to prevent pain,” she says. “That’s why it’s important to consider using preoperative and perioperative NSAIDs. Intraoperatively, of course, we try to disturb as little of the corneal epithelium as possible, beyond what’s necessary to perform intraocular surgery.

“Sometimes postoperative pain is tied to dry eye or ocular surface disease that’s gone from being relatively asymptomatic to being uncomfortable,” she adds. “Then you have to go down the pathway of doing the ocular surface examination and deciding how to manage whatever you find.”

Dr. Aminlari notes that most of the pain he’s seen postoperatively has been in connection with dry eye. “I’ve never seen serious postoperative pain, presumably because the medications we use control the inflammation in the eye and help to prevent that,” he says. “However, dry eye sometimes causes a burning sensation and blurred vision intermittently, which is another reason to look for postoperative dry eye and address it promptly.”

Managing a Decentered IOL

“In the uncommon instance that I encounter a visually significant decentered presbyopia-correcting IOL, it definitely needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Yeu. “If the patient has already had a YAG capsulotomy, that makes for a much more challenging scenario, and trying to center the IOL may not be a great option. But if the capsule is intact, you can consider reopening the bag and then trying to center the IOL.

“You have to figure out whether the IOL is decentered because there’s something wrong with the zonules, leading to uneven distribution of forces on the bag, or whether the IOL just needs to be repositioned inside the bag,” she continues. “Sometime you’re in the operating room and you try to center the IOL and you realize that it keeps creeping in one direction. The first thing you should be thinking of as the surgeon is that there’s some level of zonular laxity in that one quadrant. In such a patient, placing a capsular tension ring to provide equatorial balance of support throughout will allow you to center the IOL much more readily.”

Dr. Wallace suggests checking the haptics with the lens still inside the eye. “If a lens doesn’t seem to center properly, there may be a haptic that’s not working properly,” he notes. “It’s hard to tell, if you can’t see the haptic behind the iris. Sometimes it’s important to examine the lens while it’s still in the eye; rotate it into the anterior chamber and look at the haptics to see if there’s any abnormality there.”

|

| Above, left: Residual mixed astigmatism, undercorrected. In this situation surgical options include adding a limbal relaxing incision or opening femtosecond laser LRIs. If staying within the same meridian as an existing LRI, you can lengthen the existing LRI or place an additional LRI central to the existing one. Above, right: Residual mixed astigmatism, overcorrected. If there’s a gaping LRI, you can suture it and then place a therapeutic bandage soft contact lens. If you’re dealing with a “flipped axis” toric IOL, you can add an LRI in the opposite axis. However, quality of vision may be compromised. |

Managing a Tilted IOL

Dr. Yeu notes that an IOL that’s significantly tilted can definitely cause a refractive problem—especially when it’s a multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus IOL—and lead to refractive astigmatism shifts. “Work by Mitch Weikert and Doug Koch has demonstrated that it’s not uncommon for IOLs to tilt evenly across the horizontal axis, inducing mild against-the-rule astigmatism.2 More significant IOL tilting can occur with decentration of the IOL, capsular contraction, inadvertently malpositioned haptics (for example, one in the capsular bag and one in the sulcus), or poor coverage of the optic edge by the anterior capsule. For that reason, it’s important for us to be as accurate as possible when making the capsulorhexis or capsulotomy, which is why I use either a femtosecond laser or the Zepto capsulotomy system when I’m using an advanced-technology IOL. Those technologies allow me to create a standardized, perfectly round, well-centered capsulotomy every time. That allows for very circumferential and equal coverage of the optic edge.”

Dr. Aminlari notes that when patients present with lens tilt—which he says is very uncommon—they often need a lens exchange. “Some surgeons might want to attempt scleral fixation of the lens,” he says. “It’s possible that the zonules holding the capsular bag in place are broken, and if so, there’s nothing we can do to fix them. In those situations, probably the safest approach is to remove the lens from the eye and come up with a better solution, such as putting a new lens into the ciliary sulcus.”

The Piggyback Option

Dr. Yeu says she rarely considers implanting a piggyback lens because the lens options are limited. “We used to have access to the STAAR silicone three-piece IOL,” she points out. “That was great because it was an anteriorly round-edged, three-piece lens made of silicone, a little bit larger than a standard IOL; it could easily go into the sulcus. It came in low and minus powers, so you could use it in those patients who had a myopic or small hyperopic error.

“Now our options are a bit more limited,” she continues. “The Bausch + Lomb silicone IOL is a three-piece with a square edge, but it only goes to zero diopters, so it can’t be used in patients with a myopic error. Then there’s the AR40, which is a round-edged hydrophobic acrylic three-piece IOL; that lens is available into the minus powers. However, there are concerns that if you use the same material for both IOLs you might end up causing interlenticular opacification. I haven’t seen that happen as long as one of the IOLs is in the sulcus and the other IOL is in the bag. However, because none of our lens options are ideal, I don’t use the secondary piggy-back option very often.”

Dr. Wallace says he has occasionally resorted to implanting a piggyback lens to resolve a postoperative problem. “Some of these patients are not good candidates for LASIK,” he points out. “These are not 20-year-old myopes. They have issues like dry eye that might be made worse by LASIK. Other ocular problems such as a thin cornea could also make a patient less-than-ideal as a candidate for LASIK. You have to do a thorough evaluation of the eye, beyond just the refractive error, to figure out whether the patient would benefit from LASIK.

“One of the good things about a piggyback lens compared to LASIK,” adds Dr. Wallace, “is that if it doesn’t work properly—if there’s a degradation of visual acuity—changing the lens is better than doing a second LASIK procedure which would sacrifice more corneal tissue. That means you have an option if you later have another surprise with that eye.”

Postop Treatment: Timing Counts

Because the eye can take weeks or months to calm down following surgery—and because some postoperative problems will resolve on their own, given time—surgeons agree that holding off trying to address postoperative complaints (with the exception of a toric IOL malrotation) is important.

“If I suspect the patient just needs time to adjust to the lenses, I often won’t do much in terms of intervention until some time has passed,” says Dr. Aminlari. “Instead, I pay attention to the patient’s complaints, try to be as supportive as I can, and become their advocate. This is similar to patients who’ve just started wearing progressive-lens spectacles. They may complain in the beginning, but eventually they get used to them. Over time, patients start to neuroadapt to the multifocal or extended-depth-of-focus lenses, and in the long run they benefit from them.

“In terms of treating residual astigmatism, it’s important to wait until you’re getting measurements that are consistent,” he continues. “I typically do a refraction at four weeks; at that time we check to make sure there’s no residual astigmatism. If there is, and the patient has visual complaints, I’ll often start aggressive dry-eye therapy and have the patient return one to two months later. If the astigmatism is consistent, then I’ll perform topography and check the refraction myself. At that time I’ll make the decision about whether to do an LRI, LASIK or a lens exchange.

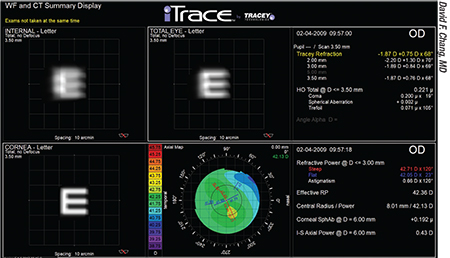

“If it’s because of toric lens rotation, the sooner you correct it, the better,” says Dr. Yeu. “Some technologies, such as the iTrace from Tracey Technologies, can measure the internal aberrations and determine what the best position of the toric IOL should be. There’s also a free application at astigmatismfix.com that can help you correct the problem. If you use that, it’s very important to know exactly what the position of the toric lens is at present; then that information has to be coupled with a very careful, accurate manifest refraction, either done by you or by an expert refractionist. Accurate data will be essential for determining exactly how much the lens implant should be rotated in order to minimize the patient’s postoperative refractive error.”

As long as the problem isn’t tied to a toric lens rotating inside the eye, Dr. Yeu says it’s important to wait to address the problem until the patient is finished with the postoperative drops. “If the patient is on generics, I will either switch over to a less-frequent dosing regimen, or initiate preservative-free medications,” she says. “Some patients just have a really tough time with preservatives. It’s not common, but I’ve seen patients whose ocular surface looks like it’s taken a beating when I see them at the early postoperative follow-up. In that situation, I give them a small sub-Tenon’s aliquot of a steroid, take them off of all other medications and do everything possible to optimize the corneal surface. The steroid will help them for the next two to four weeks. Meanwhile, I’ll have them lubricate aggressively with a preservative-free artificial tear. Once the eye looks better, I may use punctal plugs and have the patient take omega-3 supplements.”

Dr. Aminlari agrees. “Often, I find that the problem is more of a postoperative dry eye issue,” he says. “That’s why I want to give patients time to get off of their postoperative medications and use some aggressive artificial tears before I make any of those decisions.”

Robert T. Crotty, OD, clinical director at Wallace Eye Associates, says that his experience has confirmed the idea that it’s crucial to wait several months before trying to compensate for an imperfect result. “Recently, Dr. Wallace put toric multifocals in both eyes of a patient,” he says. “The first eye was great; everything went as planned and the patient was very happy. Then we did the second eye and ended up with a little residual astigmatism, and in a different direction than we would have expected. The lens was correctly aligned; there wasn’t any rotation problem. But the patient couldn’t get clear vision, and we couldn’t refract him.

| “If you ignore complaints, even if you don’t think they’re well-founded, you’ll end up with an unhappy patient.” —R. Bruce Wallace, MD |

“We were puzzled, because there was no obvious explanation,” he continues. “All of his retinal findings were normal. He had a little posterior capsular opacity, but it was very early; we didn’t want to do a YAG laser, hoping it might work, because it would make it much harder to exchange the lens if we needed to do that. We treated aggressively with lubrication, to no avail. Even though it hadn’t been 12 weeks since the surgery, we finally decided to explant the lens. However, the patient then came in so that we could redo all the measurements, and he announced that his vision was suddenly fine. We remeasured to see for ourselves, and sure enough, all the problems had gone away.

“The lesson we learned was to stick to our protocol,” Dr. Crotty concludes. “Things really do change over time. That’s why we don’t like to do anything with a patient until about 12 weeks after surgery. This patient is now perfectly happy and doing well, and we didn’t have to do a thing. But it took a little handholding and patience on the part of both doctor and patient to get through two months of poor vision.”

Postoperative Pearls

These strategies can help manage premium patients who present with postoperative concerns:

• Don’t ignore postoperative complaints, even if you feel they’re unjustified. “This has to be understood by the entire team, not just the doctor,” Dr. Wallace points out. “That includes the technicians and everyone taking care of the patient. Patients want to feel that you care. If you ignore complaints, even if you don’t think they’re well-founded, you’ll end up with an unhappy patient. At the least, have the patient return for remeasuring and don’t charge for the visit. This is basic stuff, but it helps to keep the patient happy.”

Dr. Aminlari agrees, noting that it’s important to make sure patients know you’re on their side. “Most postoperative complaints are fixable, so listening to our patients and being an advocate for them is the most important aspect of postoperative care, in my opinion,” he says. “Certainly don’t write off patient complaints. We may do a perfect surgery, but the postoperative period may not be perfect for the patient.”

| Preoperative Pearls for Preventing Postop Problems | ||

|

• Separate problems that you can address from those that are likely to resolve with time. Dr. Aminlari points out that making this distinction gets easier with experience. “That’s why it’s important to talk to patients and understand where they’re coming from,” he says. “Then, do a very thorough check to make sure that you’re ruling out the more significant potential problems such as macular edema or significant dry eye. Those things can be treated, potentially improving patients’ vision, but the majority of patients will have complaints related to high expectations. It’s important to reassure the patient, and make them understand that neuroadaptation to these lenses can take up to six months.”

• Don’t correct astigmatism based on topography alone, or before the ocular surface is pristine. “We should not be correcting a residual refractive error based on what we see topographically, especially if there’s a discrepancy between the magnitude and meridian of residual astigmatism on topography versus what you find using your IOLMaster or Lenstar,” says Dr. Yeu. “The topography data may also be altered by a Salzmann’s nodular degeneration or pterygium, so we have to clean up the ocular surface before we attempt to fix the astigmatic error.”

• Check for postoperative dry eye. Dr. Aminlari says dry eye is a significant factor in his patient population (partly because he’s located in California, where it’s usually dry and sunny). “Many patients need to be treated preoperatively for dry eye, but I also see it postoperatively,” he says. “Many of the medications we give these patients postoperatively have preservatives and can cause dry eye. So aggressive treatment of dry eye, both pre- and post-cataract surgery, will be helpful in clearing the surface of the eye to allow optimal vision. You have to remember that the first refractive surface of the eye is the tear film, so to get the best visual function, you have to optimize it.”

• Make sure your staff is educated about the lenses you’re using. “When we start offering an advanced-technology lens, we bring in the company representative to speak to our staff,” says Dr. Aminlari. “The rep tells us about some of the experiences other physicians have had with the lens. Having the staff know about these issues enables them to reassure patients who have complaints after surgery. They can also report to me what the patient is saying.

“This is especially helpful because sometimes patients are more open with a technician than they are with the physician,” he notes. “The patient may not want the doctor to think of him as a complainer, so he may not tell the doctor things that he will tell the technician. That’s another reason it’s good to have my technician be very up-to-date with the technology I’m using.”

| Preoperative Pearls (continued) | ||

|

Things are Getting Better

Implanting premium lenses can seem daunting to surgeons who aren’t already doing so, in no small part because of the potential for ending up with unhappy patients who have paid extra money out-of-pocket. However, Dr. Wallace hopes that most surgeons aren’t put off, because postoperative issues following premium lens implantation have become less and less frequent.

“I think a lot of surgeons are afraid to use multifocals because patient expectations are so much higher when you have to pay extra money for what you’re getting,” he says. “That’s true, but it’s a problem that can be addressed.

“Unfortunately, surgeons hear horror stories about certain patients and that makes them nervous about offering these lenses,” he adds. “No one wants to go back to surgery and take a lens out. But it’s important to realize that the problems that might require a premium lens explantation are pretty uncommon these days.” REVIEW

Drs. Aminlari, Wallace and Crotty have no relevant financial ties to any product discussed. Dr. Yeu is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch + Lomb.

1. Gupta PK, Drinkwater OJ, VanDusen KW, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Prevalence of ocular surface dysfunction in patients presenting for cataract surgery evaluation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2018;44:9:1090-1096.

2. Wang L, Guimaraes de Souza R, Weikert MP, Koch DD. Evaluation of crystalline lens and intraocular lens tilt using a swept-source optical coherence tomography biometer. J Cataract Refract Surg 2019;45:1:35-40.

3. Trattler W, Donnenfeld E, Majmudar P, et al. Incidence of concomitant cataract and dry eye: A prospective health assessment of cataract patients’ ocular surface. IOVS 2010;51:5411.

4. Woodward MA, Randleman JB, Stulting RD. Dissatisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:6:992-7.