|

Don't Give Up On Meds

The proposal to begin treating newly diagnosed glaucoma patients with selective laser trabeculectomy instead of traditional medical therapy challenges decades of clinical reasoning and practice patterns. I’m sure Tony Realini, MD, my debating opponent, so well-steeped in the practice and research of first treating with SLT, offers a compelling argument for making this major change. In practice we aren’t doing that. Are we just not ready? Paradigm shifts don’t come easily. The reason may be not fully apparent until we examine evidence and custom. In this counterpoint, let me elucidate my remaining questions as we consider SLT first for all.

Good Data, No Doubt

Let me first acknowledge that several prospective trials, such as the LiGHT and the WIGLS studies (led by Dr. Realini), present strong arguments that initial treatment with SLT works.1-6 We would do well to pay attention to these studies, and also to recognize that this proposal extends to treatment of ocular hypertension, not just a new diagnosis of glaucoma.

The St. Lucia WIGLS trial involved patients who had previously been treated with medications and those who were treatment-naïve. To me, the intriguing result is how effective SLT was and how long the positive effect of SLT lasted in this Afro-Caribbean population. These findings are compelling, and we should consider this possible benefit of SLT on a broader global scale.

The LiGHT study looked at newly diagnosed patients, the ones we’re discussing here. It’s worth mentioning that this wasn’t a study with a primary endpoint of outcomes, such as structural or function progression (although visual field results have been reported). Rather, the study had fewer familiar primary endpoints, such as demonstrating no difference between the groups in health-related quality of life and a very small difference in the frequency of visits at the target pressure, including 93 percent in the laser group and 91 percent in the medication group. The study couldn’t show differences in IOP control since the design was “treat in pursuit of target.”

No surgery was needed to lower IOP in the laser group, compared to 11 surgeries needed for the medical therapy group. Laser patients could be advanced to medications. Medication patients were excluded from laser. (More about the significance of this later.) The study also looked at cost-effectiveness under the United Kingdom National Health Service, but that can’t be generalized to the United States health-care system.

What does LiGHT tell me? SLT first works. Medication first works. Repeat SLT works. Medications can be added whether SLT or medication was first. We know all this, don’t we? All told, the benefits demonstrated for SLT were what I consider meaningful but secondary benefits. Have the quality-of-life and cost-effectiveness data changed our paradigm? Not yet. Why not? Please keep reading.

Adherence, Burden

In glaucoma care, we keenly appreciate issues of adherence and burden of treatment—very patient-centric aspects of care. I continue to teach that 100 percent of patients are adherent to SLT as long as they show up for the laser appointment—a rate impossible to achieve with self-administration of daily drops. We have a lot of evidence suggesting that adherence to chronic medical therapy is poor, whether it involves glaucoma drops, insulin injections or anti-rejection treatments after solid-organ transplants. We assume SLT provides a better experience for patients than administering drops one or more times a day. We can also infer that taking adherence out of the hands of patients may improve outcomes.

But accepting “SLT first” for newly diagnosed patients is not a panacea. We just don’t really see that many newly diagnosed patients. Most patients we will care for this year have had glaucoma or ocular hypertension for a number of years. New patients are relatively infrequently encountered compared to the volume of chronic cases we manage.

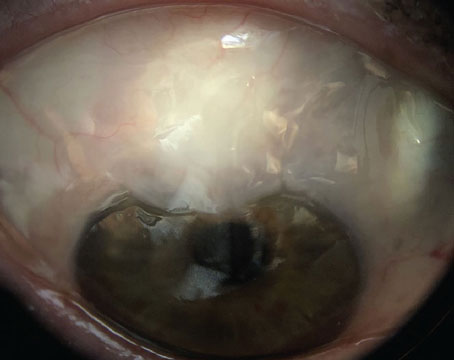

We don’t know from the data that Dr. Realini has presented how well the laser works in eyes that have undergone chronic medical therapy or if the use of SLT after medication can eliminate the need for medication. We also know SLT isn’t appropriate for some secondary glaucomas, such as neovascular glaucoma, inflammatory glaucoma or narrow-angle glaucoma.

The results of the LiGHT studies are impressive. However, we must remember an important principle: The results of a study are applicable to that study’s population and don’t always generalize well, despite the similarities some of our patients may share with some of the patients in a study. Broader, global studies will be welcome if they further support that treating patients first with SLT gives a better outcome than once-daily prostaglandin therapy as a first step.

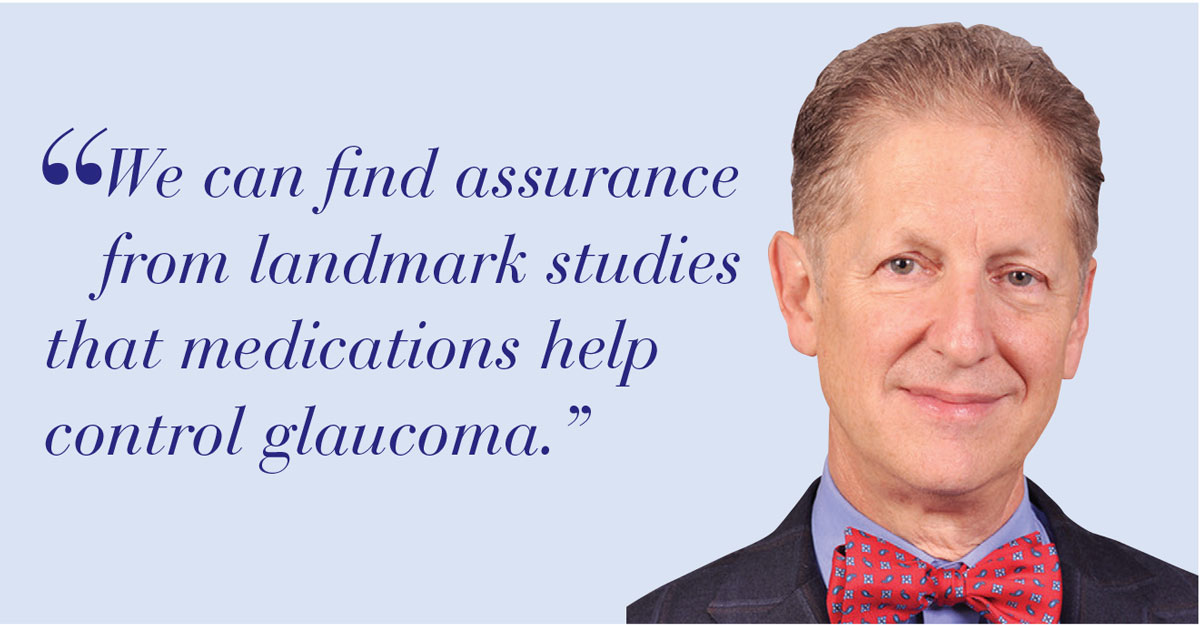

Established Treatment

The fact is that, for now, we can find assurance in evidence from landmark studies, including LiGHT, that medications help control glaucoma. Can we agree that this is not a bad thing? Medical therapy alone or medications and laser together slow progression from ocular hypertension to glaucoma (OHTS study) and progression in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients (EMGT study).7,8 The EMGT study requires some perspective because the subjects received both medical therapy and laser treatment upon diagnosis. What’s important here, though, is that we have structural and functional outcome data for the use of medical therapy alone and the combination of medical and laser trabeculoplasty, and that these data come from studies with many years of follow up. However, LiGHT study suggests that SLT first followed by medication, compared to medications alone, produced a better visual field outcome several years down the line.

Another important point worth considering: We can offer SLT first, but it doesn’t eliminate the eventual need for medications. In another very recent study, (selective laser trabeculoplasty versus topical medication), researchers found that at month 24, successful IOP reduction was 18.6 percent better in the medication group compared to the SLT group.9 Even if we agree that using SLT first offers patient-centric benefits, we might expect half of those patients to require medication within two years, according to this study. Two additional years free of glaucoma medication is a worthwhile quality-of-life benefit. It’s unknown if offers an improved outcome.

Granted, the researchers in this most recent study used a different approach to laser treatment than what was used in the LiGHT study. I believe this is one more point that demonstrates that we still have more to learn when it comes to SLT followed by medication or vice versa.

We don’t have clarity yet on what to do when the beneficial effects of the laser wear off. Will a repeat SLT provide additional years of control? I believe it will, at least for some patients. Then we add medication.

Access to SLT

SLT first works only if patients have access to SLT. We assume when we say SLT first that patients can actually get access to laser treatment. That isn’t always the case, given the misdistribution of health-care resources. Not every physician’s office has a laser. For at least some patients, finding access to a laser treatment would pose a burden on them.

We also need to recognize that we’re debating this issue in a wealthy, developed nation, not in less-advantaged countries, where patients have just as much need for an effective treatment of glaucoma. An environment where there are few ophthalmologists, no lasers and no intact medication distribution channels makes our question irrelevant. Inequities—which also exist among patients with little or no access to care in our country—raise troubling public-health questions. We must appreciate that many of the fortunate among us in this country have the luxury of considering both options.

We also have a scope of practice in the United States that would prevent some patients from immediately accessing initial SLT. New diagnoses of ocular hypertension and glaucoma are often made by optometrists. The use of the laser by optometrists is limited to Alaska, Kentucky, Louisiana and Oklahoma. A substantial change in practice patterns would have to occur for optometrists to refer all newly diagnosed glaucoma patients to ophthalmologists for laser surgery. The social and economic barriers would likely be difficult to resolve.

Finally, while I see compelling evidence that the laser can be equally effective, at least initially, and for offering secondary benefits, we need to make sure we don’t dismiss the utility of medications. Some patients won’t respond to SLT, or the efficacy will diminish over time.

How Long?

One final thought to close my side of this debate: Even if we reach a consensus on SLT-first treatment, we’re introducing evidence-based changes that may take many years to adopt. I’m reminded of a classic paper that shows us that 17 years typically passes between the time when meaningful research calls for evidence-based changes in patient care and the time when those changes reach clinical practice.10 So, what are we waiting for? Go ahead. Adopt first-line SLT for most patients newly diagnosed with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. But remember the many barriers, including several that aren’t under our control at this point.

Dr. Fechtner is professor and chair of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at SUNY Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. He has published widely on medical therapy for glaucoma, but is thankful to have an SLT laser down the hall.

Dr. Fechtner consults with Aerie and Nicox.

1. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019:293:0180:1505-1516.

2. Realini T, Shillingford-Ricketts H, Burt D, Et al. West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study (WIGLS): 1. 12-month efficacy of selective laser trabeculoplasty in Afro-Caribbeans with glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;184:28-33.

3. Realini T, Shillingford-Ricketts H, Burt D, Et al. West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study (WIGLS)-2: Predictors of selective laser trabeculoplasty efficacy in Afro-Caribbeans with glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2018;27:10:845-848.

4. Realini T, Shillingford-Ricketts H, Burt D, Balasubramani. West Indies Glaucoma Laser Study (WIGLS) 3. Anterior chamber inflammation following selective laser trabeculoplasty in Afro-Caribbeans with open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2019;28:7:622-625.

5. Realini T, Olawoye O, Kizor-Akaraiwe N, et al. The Rationale for selective laser trabeculoplasty in Africa. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2018;7:6:387-393.

6. Polat J, Grantham L, Mitchell K, Realini T. Repeatability of selective laser trabeculoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 2016;100:10:1437-41.

7. Kass MA, 1, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: A randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:6:701-13.

8. Anders Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, et al. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: Results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol, 2002;120:10:1268-79.

9. Ghee Soon Ang GS, Fenwick E, Constantinou M. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus topical medication as initial glaucoma treatment: The glaucoma initial treatment study randomized clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:6:813-821.

10. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011; 104:12: 510–520.

Time to Stop the Drops

|

If you were diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma today, would you prefer selective laser trabeculopasty or medical therapy? If you’re like most of the ophthalmologists I’ve spoken to during the past 10 years, you’d raise your hand for SLT. But suppose I asked how many of your patients with newly diagnosed POAG receive primary SLT—would you join most of our colleagues and lower your hand?

That’s the conundrum I encounter frequently: Doctors who treat their patients differently than they would want to be treated themselves. And here’s my confession: I used to be one of those doctors. I’ve given a lot of thought to my transition from meds-first to laser-first, and I’ve identified a handful of issues that I had to overcome along the way. In this point-counterpoint article, I’ll take the laser-first position, and I’ll explain why my practice has evolved this way. My goal is not to convince those who believe in medications as the first line of treatment for most patients; instead, I’m talking to the many of you out there who are ready to make the transition and need that last gentle nudge to make it happen.

First: The Why

Why am I advocating for SLT to be the preferred first-line treatment for glaucoma? What’s so great about it that we would even discuss a paradigm shift in treatment? If you’re one of the many ophthalmologists who would hypothetically prefer first-line SLT if you were diagnosed with glaucoma, you’ve already answered this question for yourself, so ask yourself why you feel this way.

There are a number of good reasons. The most important consideration—efficacy—will be discussed more fully below, but suffice it to say that primary SLT is as equally effective as daily prostaglandin analog therapy, which the vast majority of your patients who aren’t receiving primary SLT will end up taking. Safety is another key concern. Many patients will experience mild pain and inflammation for a few days after SLT, but the evidence for sight-threatening complications of SLT exists in the medical literature only at the level of case reports.

I’ve encountered far more common and more severe adverse events from topical therapy than from SLT. Cost is also a factor. At a systems level, the SLT-first approach has been shown to be more cost-effective to the health-care system than a meds-first approach.1 At a patient level, insurance may not cover drug costs but will cover procedure costs, and for uninsured patients, SLT is cheaper in the long run than buying medications every month (although the cost is all up front, rather than being amortized over the patient’s lifetime).

These are good reasons to choose SLT over medications, but not the best ones. The best single reason is this: SLT keeps people off medications. Don’t get me wrong—there’s nothing inherently wrong with medications. But there’s nothing inherently right about them, either. They burn, they sting, they make the eyes red, and these symptoms are magnified in the 50 percent or more of glaucoma patients who have concurrent ocular surface disease. For generally asymptomatic patients with mild to moderate glaucoma, topical therapy imposes a burden that’s worse than the disease from their perspective.

It’s no wonder adherence to medical therapy is notoriously poor and nonadherence compromises intraocular pressure control and leads to disease progression in so many patients. Why would we pick a treatment that many of our patients won’t use, knowing their nonadherence could worsen their glaucoma? As my mentor Rob Fechtner, MD, arguing the other side of this issue on page 50, once told me, “There’s never been a documented case of nonadherence to trabeculoplasty.”

I have to underscore this point: SLT keeps people off medications. The American Academy of Ophthalmology and the European Glaucoma Society assert that the ultimate goal of glaucoma therapy is to preserve quality of life. The commitment of daily self-dosing, the costs and the side effects associated with medical therapy take a toll on quality of life. Many of you have already reached the conclusion that reducing or eliminating the medication burden is an important goal when caring for glaucoma patients. This is why you offer minimally invasive glaucoma surgery with elective cataract surgery. You know they’ll be happier on fewer or no drops. So why are you still starting them on drops in the first place?

Seeing the LiGHT

Despite the benefits of SLT, one thing has been missing: high quality data. We can’t expect to drive an evidence-based treatment paradigm change without evidence. The recent LiGHT study (Laser in Glaucoma and ocular HyperTension) provides this crucial missing piece.1

The three-year (and ongoing), 718-patient LiGHT study was well-designed, adequately powered and well executed. Treatment-naïve patients with mild-to-moderate POAG or high-risk ocular hypertension were randomly assigned to SLT or medical therapy (starting with a prostaglandin analog) as first-line treatment. The results? IOP control was comparable in both groups, but more eyes in the medication group than in the SLT group had disease progression (36 versus 23), and all 11 eyes requiring trabeculectomy were in the medication group. At three years, 60 percent of SLT eyes remained medication-free after a single treatment, and 78 percent were medication-free with one or two SLT treatments. By comparison, 65 percent of eyes in the medication group were well-controlled on a single medication at three years, while 35 percent required additional adjunctive therapies. Interestingly, achievement of target IOP was 93 percent in the SLT group and 91 percent in the medication group. Thus, the higher progression rates and surgical rates in the medication group suggest some patients in the medication group may have taken their medications only at the time of study visits and had higher IOP between visits, leading to progression and the need for surgery.

Time for a Change

At this point, I hope you’re convinced that primary SLT offers a better quality of life than medical therapy for many of our patients. When I decided 10 years ago that I wanted my patients to benefit from primary SLT, I encountered key barriers created by what I call the four “Ts”: Time; Talk; Transience; and Timing. Here’s how I overcame them to provide primary SLT to more than 90 percent of my newly diagnosed patients.

• The Time issue. Time is precious, especially when we’re face-to-face with our patients. Many ophthalmologists have told me that it just takes too much time to discuss SLT versus meds. It’s far easier and faster to write a prescription for a prostaglandin analogue. This is true. However, those of you who perform MIGS have decided that the discussion time is worth investing to reduce or eliminate your patient’s glaucoma medication burden at the time of cataract surgery. And those of you who implant premium IOLs have decided that the discussion time for these upgrades is worth investing to improve quality of life through spectacle independence. Treat your SLT discussion the same way—if you believe it’s the right thing to do (like MIGS and/or premium IOLs), you’ll find the time to discuss doing it.

• The Talk issue. How we talk to our patients about SLT determines their interest in the treatment. My informed consent discussion has evolved over time in concert with my attitudes toward SLT. Initially, I presented SLT as an alternative to the standard approach of medical therapy, which—in the early days—it was. Not surprisingly, fewer than 5 percent of my patients opted for SLT. Who wants to deviate from the standard of care? Over time, I came to believe that these treatment options were equal in quality and that I should present them accordingly. When I began telling patients that we have two good treatment options, described them both, and asked which they preferred, about a quarter of my patients opted for SLT.

As my own experience with SLT grew—both in the clinical and the research arenas—I came to believe (in all the ways described above) that SLT was better than medications for most patients (which is why most of us ophthalmologists would want primary SLT for ourselves). Once I started sharing with patients that I would select SLT for myself if I had their eyes, patients rarely chose medical therapy. After all, who would want a different treatment than the one the doctor would want for himself? For those of you who may view this approach as too paternalistic for the new age, ask yourself this: If you had cancer, would you want your oncologist to offer you treatment options without ranking them best to worst and let you pick one, or would you want her to succinctly synthesize everything she knows about cancer and its treatment by telling you what she thinks is the best option for your cancer?

• The Transience issue. SLT wears off over time, typically within a few years for most patients. SLT can be safely repeated, however, and restores IOP to the same level achieved by the first SLT. There are no reports in the peer-reviewed literature of unique complications of repeat SLT after 20 years of its use. If the fact that SLT isn’t permanent keeps you from using it, remember that prostaglandin analog therapy wears off too, every day, and has to be repeated every day as well. My patients understand that sitting still for five minutes every few years is preferable to sitting still for five minutes every day for self-administration of drops.

• The Timing issue. Once you start doing SLT, you’ll find that popping in and out of the laser suite can disrupt the flow of a busy day. Here’s my pearl: The first three appointments in every one of my clinic schedule templates are laser slots. I perform them all up front, at the start of the clinic session, so I can then remain focused on patient flow and stay on schedule.

It’s Time

In the glaucoma world, 2020 is the age of enLiGHTenment. The time is right for a paradigm change. Our patients are well-informed, and their expectations have never been higher. We have data to support an evolution in practice patterns. Let’s make it happen. REVIEW

Tony Realini, MD, MPH, is a professor of ophthalmology and glaucoma fellowship director at West Virginia University in Morgantown. He has no financial relationships with any SLT manufacturers.

1. Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;393:1505-16.

2. Katz LJ, Steinmann WC, Kabir A, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus medical therapy as initial treatment of glaucoma: A prospective, randomized trial. J Glaucoma 2012;21:460-8.