Phakic intraocular lenses are sort of an “option of last resort” for patients who really want refractive surgery but don’t qualify for LASIK or PRK due to high refractive errors or corneas that are too thin. Though they expanded the range of refractive surgery when they arrived in the United States years ago, they didn’t catch on in the way some hoped. Even so, phakic lenses remain a viable option for certain patients, and surgeon interest may increase if and when the latest version of the Visian ICL is approved.

If you’ve got patients who might qualify for one of these lenses and want a primer on implantation, or you’ve already implanted a couple and want to hear how other surgeons approach them, read on.

Phakic IOLs in the United States

Currently, the Visian ICL and Ophtec’s Verisyse/Artisan are the only phakic IOLs approved in the United States. “The toric version of the ICL was recently FDA approved and is terrific for patients who have astigmatism,” says John Hovanesian, MD, who is in practice in Laguna Hills, California. “These lenses are indicated for myopia or myopia with astigmatism, and they work very well. Some docs feel that the results they achieve with phakic IOLs are better visually than the results they get with LASIK.”

According to Santa Clara, California, surgeon Huck Holz, MD, most surgeons in the United States favor implanting the Visian ICL. “The Verisyse requires a larger incision, the recovery is slower, and outcomes are not as predictable,” he says. “We also have to worry over the long term about the patient’s endothelial cell counts, so most people have gravitated toward the ICL.”

Patient Selection/Education

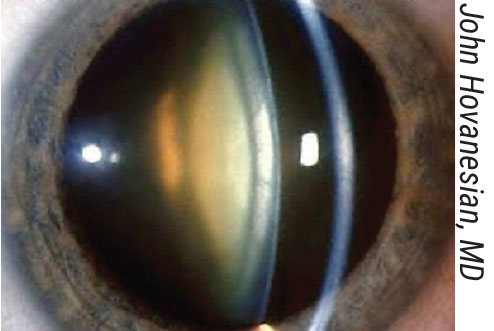

Ideal candidates for phakic IOL implantation are relatively young patients who have high myopia and are looking for good-quality vision. “This is a reasonable option even for patients with keratoconus, provided that spectacle correction gives them a satisfactory outcome,” Dr. Hovanesian says. “One of the nice things about an ICL is that, if patients see well with spectacles, then you know that they’ll see well with an ICL. Additionally, if patients are in their 50s, they are high myopes, and they are not ready for cataract surgery, an ICL is still a reasonable option.”

Minneapolis surgeon David Hardten notes that patient education is important. “Most refractive surgery patients haven’t thought about phakic IOLs,” he says. “Most of their friends have had LASIK or PRK, so we need to have a plan for how to talk to patients when they have never heard of phakic IOLs. Otherwise, they’ll seek out other docs to try to find someone who will do LASIK or PRK for them, despite the fact that you feel like a phakic IOL is definitely their best option. I try to give patients a definitive answer rather than a choice. In this situation, if I feel that a phakic IOL is best, I don’t really give them the option of PRK or LASIK.”

To help patients understand the procedure, Dr. Hardten tells patients that the implant is like getting a contact lens implanted in their eye. “I let them know that, because of their age, their natural lens still has range of focus, so the implant goes over their natural lens,” Dr. Hardten says. “This provides a better outcome than we would be able to achieve with LASIK or PRK. Most patients understand, but it’s not uncommon for them to return for a second discussion.”

Preop and Intraop Tips

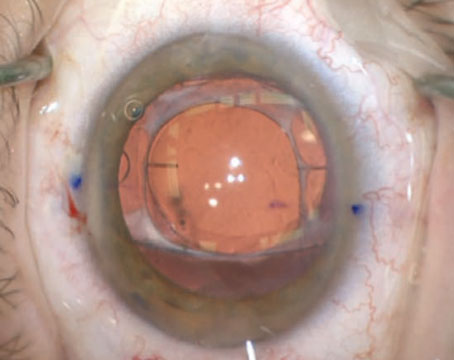

Dr. Holz says that sizing is everything with phakic IOLs. “I always tell patients there’s a small chance of having the lens removed and replaced with a lens that’s going to be more appropriate for the size of their eye,” he says. “You must be fastidious about your white-to-white measurements. It’s a great idea to check sulcus diameter with ultrasound biomicroscopy as a corroborative measurement.

|

| Proper white-to-white measurement is key for the ICL. |

“The company has developed nomograms to help surgeons determine which lens is the appropriate size for a particular eye,” he continues. “The ICL must be well away from the crystalline lens, but it has to not be so vaulted that your lens creates a posterior pushing glaucoma mechanism because you’re closing the angle. In the rare situations where the lens is vaulted so much that it’s pushing posteriorly against the iris and closing the angle it should be replaced if you have elevated intraocular pressures that persist.”

Lance Ferguson, MD, in practice in Lexington, Kentucky, strongly recommends general anesthesia. “Even minor movement from the patient can lead to disaster,” he says.

Dr. Hardten does most of his phakic IOL cases under topical anesthesia, but does them in the ambulatory surgery center, where he can use IV sedation as needed. “Small amounts of IV sedation like we use for cataract surgery keep patients much more comfortable,” he says. “Then, I rinse the viscoelastic out with bi-manual irrigation/aspiration, which I think reduces the tendency to have issues like postoperative IOP rise, and is easy to do in the ambulatory surgery center by removing all of the viscoelastic at the end of the case. Having the pupil reasonably well-dilated, but not extremely dilated, is very helpful in being able to tuck the haptics of the Visian underneath the iris without necessarily having it come back up out of the sulcus into the anterior chamber. We use just one drop of tropicamide preoperatively. Intraoperatively, I have a little bit of epinephrine in my lidocaine solution, and that typically provides reasonable dilation in most of these patients.”

Dr. Ferguson recommends that either the surgeon or a trusted tech load the IOL. “It’s kind of tricky to load,” he says. “You must align two tiny apertures in the ICL to ensure you’ve achieved the proper orientation. If aligned properly, you prevent the ICL from flipping over during injection, and it’s imperative to avoid any unnecessary manipulation of the ICL in the anterior chamber. You can confirm proper alignment by looking for symmetrical delivery of the wingtips as they pop out of the injector. Stay anterior to the iris and back the injector out a little bit as you deliver the tips of the back haptic. Once the lens is in the eye and properly oriented, you can add more OcuCoat (Bausch + Lomb) to give yourself additional working room. Then, use a paddle to position the tips of those haptics posterior to the iris. The paddle is the perfect instrument for this maneuver, as its curvature allows contact solely with the tips of the plate haptics and avoids any touch of the central optic, as posterior displacement could press against the crystalline lens and possibly lead to cataract formation.”

According to Dr. Holz, phakic IOL implantation is quick and easy. “One pearl is to make a peripheral iridotomy either in the clinic or intraoperatively,” he says. “My preference is to do this with a vitrector at the time of surgery because it’s so quick, easy, and reliable. However, this will soon no longer be necessary. The EVO ICL [see sidebar, left] with a small port in the center will soon be available in the U.S., which we’re all looking forward to. It will have a very small drain for aqueous in the center of the lens, so peripheral iridotomies will no longer be needed.”

Dr. Holz recommends dilating eyes with tropicamide. “Only use tropicamide, so the pupil comes down a little faster with Miochol (Bausch + Lomb) instillation during surgery,” he says. “Other pearls would be loading the lens yourself under the microscope. It’s not the easiest or most intuitive loading system, so most technicians aren’t able to do it.” Dr. Hardten also prefers to load the IOL himself, especially because he doesn’t always work with the same surgical tech.

Dr. Hovanesian adds that one of the most challenging parts of the procedure is avoiding touching the crystalline lens with anything but viscoelastic. “If you’re going to touch it, do so only very peripherally and not in the optical center of the crystalline lens,” he advises. “There are plenty of videos online showing implantation. Following the recommendations of the manufacturer and the videos that you see is really the best advice.”

Dr. Hardten prefers to do each eye separately. “Usually, we separate them by a few days or a week, depending on patient preference,” he explains. “I operate out of two different locations. I’m in each of my locations once a week, so some of the patients are willing to travel between locations [to have the surgery] a couple of days later, but I typically do them about a week apart. Because I got all of my measurements the first time around when they’d been out of their contact lenses, I let them wear their contacts in between the two eyes, which solves most of the issues with the anisometropia.”

First Look: Visian ICL V4c with CentraFlow This lens has a central artificial hole called the KS-AquaPort that was added to the center of the ICL optic to improve aqueous humor circulation in the eye. This eliminates the need for a preoperative peripheral laser iridotomy or intraoperative peripheral iridectomy, which the company says simplifies the surgical procedure and significantly reduces the complications associated with iridotomy. A retrospective cohort study included 17 eyes implanted with the ICL V4b model and 18 eyes implanted with the ICL V4c model. The mean preoperative spherical equivalent refractions were -7.48 ±5 D for the V4b design and -8.66 ±4.2 D for the V4c design. Three months postoperatively, the mean uncorrected distance visual acuities were -0.09 ±0.12 logMAR with the V4b and -0.07 ±0.11 logMAR with the V4c. Mean distances between the ICL and the anterior crystalline lens surface were 557 ±224 μm for the V4b and 528 ±268 μm for the V4c. The mean IOPs were 13.7 (V4b) and 13.3 mmHg (V4c) after one week and 14.7 (V4b) and 15.1 mmHg (V4c) after a month. No significant differences in IOP were observed within or between groups during the follow-up period.

1. Higueras-Esteban A, Ortiz-Gomariz A, Gutierrez-Ortega R, et al. Intraocular pressure after implantation of the Visian Implantable Collamer Lens with CentraFLOW without iridotomy. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:4:800-805. |

Postop Pearls

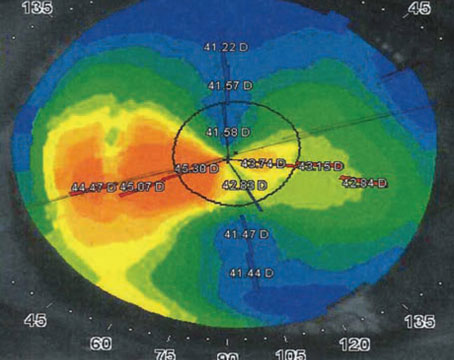

According to Dr. Holz, the toric version of the phakic IOL is different from typical toric IOLs implanted for cataract surgery. “The lens toricity is built into the [phakic] lens to match the patient’s astigmatism,” he says. “The lens is implanted in the horizontal meridian and rotated only up to 22 degrees off the 180-degree axis to ensure proper sizing for the sulcus and that the peripheral iridotomy isn’t blocked. The toricity is imprinted in the lens at the desired axis of the patient’s astigmatism so the lens only has to be rotated minimally from the horizontal meridian. This is quite different from the current version of toric intraocular lenses that we implant for cataract surgery [which need to be rotated in order to line up the toric-correction axis of the lens with the patient’s steep axis.]”

Outcomes

According to Dr. Hardten, the recovery process is quick, especially with the Visian implant. “These patients with extreme myopia are 20/20 or 20/25 on day one, and they tend to be very stable over time,” he avers. “It’s just impressive how happy patients are. It’s sort of like they forgot to take their contacts out.”

He recommends that patients be seen annually after implantation of a phakic IOL. “Their natural lens will grow over time, and that growth can then change the anatomical relationships inside the eye,” he warns. “The natural lens can push forward on the implant, so it can shallow the anterior chamber. These patients need to be observed for glaucoma, cataract formation and endothelial cell issues.

“I’ve been doing phakic IOLs now since 2000,” he adds, “and it’s kind of fun to see some of the patients coming in 20 years later who still have the 20/20 vision they’ve had from day one. These patients will eventually develop cataracts around age 60 to 65, like everyone else. At that point, we remove the phakic IOL and the crystalline lens, and implant an IOL.”

The Future of Phakic IOLs

According to Dr. Holz, there’s a growing subset of patients with extreme myopia. “These are high myopes who absolutely hate their glasses,” he says. “They often run into problems with contact lenses because they overwear them, because they can’t deal with wearing glasses, even at home. They’re sort of in a pickle refractively, and so we need to have a refractive solution for them.

“For patients in their early 40s and younger, the retinal detachment risks associated with clear lens exchanges are too high, and they also stand to lose their accommodation with these refractive lens exchanges,” Dr. Holz continues. “So, for those patients who are younger than 50, we think about doing phakic IOLs because they get to preserve their accommodation, and there’s a lower chance of retinal detachment. Satisfaction rates are quite high with this modality. And we can look forward to further advancements in this technology, since the need for these lenses certainly isn’t going away.”

None of the authors have a financial interest in any product mentioned in the article.