|

Changing the Channel

One of the problems that can occur with implanting ICRS is the false channel, where the segment takes an incorrect path through the cornea, rather than following the one created for it. This can happen even if one uses a manual technique for channel creation if the blade follows the wrong path. “The manual approach can sometimes go too deep or too shallow,” says Soosan Jacob, MD, of Chennai, India. “Or, it might stay at the correct depth but go outside the path that you intended; it might point too much toward the limbus or too much toward the pupil. In both cases, you might have to abort the procedure.” The segment may also be directed posteriorly and cause a perforation.

“Because of these possible complications, many surgeons now choose to use the Intralase to create the channels,” says Dr. Jacob. “The Intralase allows you to precisely program the depth you need, the inner and outer channel diameter and the location of the incision. It also allows the creation of a complete 360-degree circumferential channel, unlike the manual method in which circumferential channels are usually not possible.”

|

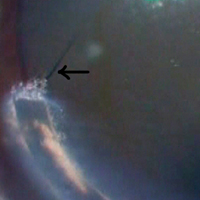

“If you hold the segment at an angle to the entry cut it will sometimes miss the proper Intralase channel and start dissecting a false one,” Dr. Jacob adds. “You can also inadvertently angle it posteriorly or anteriorly. Then, once the false channel starts being dissected, it’s extremely difficult to reopen the Intralase channel, as it will just collapse. If you remove the segment and reinsert it, it will enter the false channel again. This is because there is an internal lip composed of some of the corneal collagen lamellae that is separating the Intralase channel from the false channel. This lip acts as a barrier to the Intralase channel and redirects the segment into the false channel. This lip will be visible if you look carefully.” Dr. Jacob says you can detect the beginnings of a false channel by the resistance you feel as you insert the segment. “Under normal circumstances, it should go in smoothly with a series of small horizontal pushes,” she says. “But, if at some point you start to feel resistance to the forward movement of the segment, that’s an indicator you might have a false channel. The other sign is radiating or curved corneal folds around the advancing edge of the segment.”

False channels can lead to a few problems. First, you might have to abort the full procedure and just settle for having one segment implanted on the side without the false channel, says Dr. Jacob. “The second scenario is that you keep pushing the segment in too much of a posteriorly angulated direction, rather than on a horizontal plane,” she says. “This can lead to a perforation of the anterior chamber. Third, you may unintentionally push it so that it goes anterior and its tip is lying superficially in the cornea rather than in the horizontal plane of the Intralase channel. In situations where the segment is anteriorly angled, the corneal lamellae overlying the segment may not be sufficiently thick, and this can cause a corneal melt in that area and extrusion of the segment. Untreated, this can result in infectious keratitis that’s very difficult to treat, since infections in the setting of foreign bodies—in this case the Intacs segment—can be more difficult to manage. In the instance of an eroded segment, you must immediately remove the segment to avoid infection.

|

Turn It Around

Though a false channel prevents you from entering through the blocked side of the Intralase channel, Dr. Jacob has developed a technique that allows you to complete the case.

“In the turnaround technique, you first withdraw the segment that is creating a false channel,” she explains. “Recall that the Intralase creates a 360-degree channel. So when you then turn the segment around, you can enter the channel from the opposite side. You push the segment in as far as it will go. Once it reaches as far as it can be pushed in with a rod or other blunt instrument, you take the second segment and use it as an intrastromal instrument to keep pushing the first segment further forward. The second segment is perfect for this, because it has the same arc as the channel and its edge fits snugly with the edge of the other segment. As you do this maneuver, the first segment will finally rotate all the way around and meet the lip that obstructed it in the first place. Now however, since you’re coming from the other direction, the segment will flatten the lip and it will thus reenter the channel from the opposite side.” This technique is effective when the segments are symmetrical.

However, there are patients with decentered cones for whom symmetrical segments don’t work, and the surgeon needs to use an asymmetrical pair. In these cases, the thicker segment is usually implanted inferior to the cone, with a thinner segment implanted superiorly. “With asymmetrical segments, if you encounter a false channel while inserting the second segment and then perform the turnaround technique, you might end up in a situation where the thicker segment is superior and the thinner is inferior,” explains Dr. Jacob. “In this case you can do what I call a double-pass turnaround technique. In this maneuver, with the segments in place but in opposite positions—in other words the thin one on the bottom and the thicker one on the top—I use a reverse Sinskey hook to engage the positioning hole of the thicker segment and pull it out through the entry incision. I then reintroduce the thicker segment again into the side without a false channel and use it to push the thinner segment forward through the channel until the thinner piece is in the superior position and the thicker is inferior as planned.”

Other Complications

As mentioned earlier, a segment in a false channel can result in complications such as extrusion and chamber perforation. Here are ways to manage these other adverse events.

“If you encounter an infection due to a segment extruding, you have to remove the segment immediately and irrigate the channel with antibiotics,” says Dr. Jacob. “The segment should be sent for culture and sensitivity. Start a course of hourly broad-spectrum fortified antibiotics and change them according to the results of the sensitivity reports. When the infection is under control, you can begin tapering the drugs. If you can’t control the infection with intensive medical management, you sometimes have to perform a penetrating keratoplasty.”

If a corneal perforation occurs, the management strategy depends on the size of the perforation, says Dr. Jacob. “It will usually be small, and you’ll immediately feel the perforation occur in the form of a lot of resistance; you’ll know you’ve entered the anterior chamber. If this happens, immediately withdraw and put an air bubble in the anterior chamber, which will tamponade the perforation from inside the eye. Remove the segment and then suture the entry incision. The prognosis is usually good, since the perforations are usually small and peripheral, lying outside of the visual axis.”

REVIEW