It’s no secret that some cataract—and now retina—practices have opted to create in-office surgical suites. Proponents say offering in-office surgery gives them increased flexibility as well as staff and equipment advantages compared to hospitals or ASCs. Other physicians wonder, however, about the specter of endophthalmitis, anesthesia problems, reimbursement issues and other concerns.

Here, to help shed light on this evolving situation, several surgeons, one of them a retina specialist, share their stories about going down this path, and discuss the questions that often come up when surgeons consider doing this.

Bringing Surgery In-house

Orest Krajnyk, MD, a board-certified cataract and refractive surgeon in New Smyrna Beach, Florida, and a physician CEO graduate from Kellogg Business School, set up his in-office surgery center three years ago. He explains that his family had decided to move to the east coast of Florida. “At an ophthalmology meeting I heard a discussion about setting up an ASC in New Smyrna Beach because the doctors were tired of having to do surgery in local hospitals,” he says.

“I ended up meeting Tony Burns, MBA, CASA, CSFA, who had built several ASCs and begun setting up in-office surgery suites,” he continues. “He said that getting 10 doctors to set up a surgery center would be much more of a challenge than we realized, and it turned out he was right. Tony and I stayed in touch, and one day he offered to make me the first client of a new in-office surgical set-up company he’d started, iOR Partners.

|

| Orest Krajnyk, MD, says his in-office surgical suite is profitable, thanks in part to his being in control of equipment and costs. He also uses it as a marketing tool. His OR features adjustable-color lighting to help patients relax. Photo: Orest Krajnyk, MD. |

“There was extra space available next door to our office, so I took that over and set up there,” he says. “In June of 2019 I opened up my in-office surgery center, with two ORs, a clean-and-dirty room in the middle, and a preop-postop area in front of it with massage chairs. The whole project cost 10 or 20 percent of what it would have cost to build an ASC.

“I was a little nervous,” he notes. “Being the first practice to work with iOR was a leap of faith, but I trusted the people I was working with. They came in, credentialed us and helped us set everything up. If there are complications, we have a protocol. And we’re certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities, so it’s not like we’re just doing this casually.”

Dr. Krajnyk says he currently uses the surgical suite once a week. “If it gets busier, I can add days as needed,” he notes. “I do 15 to 20 cataracts a week or so, all in one day. I start at about 8:30 and I’m usually done by 2 or 3 o’clock.”

Dr. Krajnyk recalls that when it was time to reopen after the six-week COVID shutdown, he was the first cataract surgeon in his area to be back up and running. “I was operating one day after the shutdown ended, and I was caught up within the first week,” he says. “Some of my colleagues had to wait two months after reopening to do surgery because the surgery center said, ‘Cataract surgery is elective surgery. You can’t do it yet.’

“I’ve now done more than 1,300 cataract surgeries in our surgical suite,” he concludes. “I’ve had zero infections, zero vitrectomies and no complications. My staff knows exactly what to do. And we’ve done well financially because we’re in control of our own equipment, costs and reimbursement. Furthermore, I have the only in-office surgery center in this county. Patients are often very impressed that we’ve done this in our tiny little community, so it’s a marketing tool as well. I wouldn’t think twice about making that decision again.”

Dr. Krajnyk says although it’s possible to set up an in-office surgical center on your own, he believes it might not be advisable. “I’ve seen people do it and it turned out OK,” he says. “But it’s a tradeoff; you spend less money but a lot more time solving problems and finding the right way to do something. And, with outside help, the agency shares some of the liability if something goes wrong.”

Striking Out on His Own

Robert F. Melendez, MD, MBA, the CEO and founder of the Juliette Eye Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which has its own surgical center, says he was part of a very large practice for 16 years, where he did 2,000 cataracts per year. “The average surgeon does 300 to 500 per year,” he notes. “I did 32 per day. I thought that was normal.

“When I decided to start my own practice two years ago, COVID hit,” he continues. “I believe that patients prefer a more ‘premium’ experience, so I looked at ways to make that possible. I wanted to have a great website, a new building, the newest technologies and customer service that would knock patients’ socks off, and offering office-based cataract surgery seemed like a great way to enhance the patient experience. Sending them out to a surgery center is the way it’s always been done, but that doesn’t mean we should continue down that road.” Coincidentally—Dr. Melendez also wound up working with iOR Partners.

|

| Robert Melendez, MD, MBA, says his in-office suite is perfect for his premium practice. He says the majority of his cataract surgeries can be done there, and patients are very happy—even requiring less sedation during surgery. Photo: Robert F. Melendez, MD, MBA. |

“They helped us check all the boxes and stay organized, get the proper accreditation and figure out what committees we needed to have in place,” he says. “They also provided a very robust EHR system that tracks all of the information from inventory to the patient’s operative status and the results of the history and physical we do. Then they helped us with coding and billing. This has made it very seamless for us, which allows us to spend more time with the patient, enhancing their experience. The company will also train your office’s staff, if need be.

“When I started my new practice, I predicted that I’d do about 40 percent of my cases in my office-based surgery suite and 60 percent in the local ASC,” he notes. “But as I started doing in-office surgery, I realized that I could do most of my patients here. The only exceptions were patients with uncontrolled comorbidities and serious illnesses. Those patients should be done in a surgery center with an IV, giving them more sedation and a more controlled environment.

“I was shocked by how effective office-based surgery is, how safe it is, and the great outcomes we’ve produced,” he says. “If you’d told me a couple of years ago that I’d be doing office-based surgery, I would have said you were crazy. I wasn’t aware of anyone doing that here in New Mexico. Now, three of my friends have started office-based surgery suites in the past year.”

Dr. Melendez says patients are thrilled to be able to get their surgery done at his office. “The patient experience is definitely enhanced with office-based surgery,” he says. “Patients come to the same location as they do when I see them in the clinic, so their anxiety level is already diminished. They don’t have to drive to a different surgery center, get lost and end up running late, which gets them all worked up by the time they get there on the day of surgery.

“In fact, we’ve found that patients require less sedation, which creates an overall better patient experience,” he continues. “Patients get to see the same staff they just saw two or three weeks prior for the exam, and patients know them.”

Managing Retinal Emergencies

Another group of doctors who might benefit from having an in-office surgical suite is retina specialists. Jonathan Feistmann, MD, a retinal specialist practicing at NYC Retina in New York City, and his partner, Julia Shulman, MD, set up their own in-office surgical suite earlier this year. His story clearly illustrates the potential benefits of this situation.

“The reason we’re doing office-based surgery is out of need,” he explains. “As retina specialists, patients are frequently sent to us with urgent, time-sensitive retina emergencies such as retinal detachments. We get calls like this several times a week. We’re faced with an individual freaking out because they’re losing their vision, and of course they want it fixed right away.

|

| Retina specialist Jonathan Feistmann, MD, says his in-office surgical suite allows him to manage retinal emergencies without having to beg local hospitals and ASCs to find an open time slot for him to help the emergency patient. Photo: Jonathan Feistmann, MD. |

“Before we had our in-office surgical suite, my concern in this situation wasn’t so much about the retinal detachment, because I know I can fix that,” he continues. “My concern was getting time in an OR—figuring out where to take the patient and when we could get the patient in. When this happens in the middle of a busy day, we suddenly have multiple staff stopping what they were doing to make frantic phone calls to surgery centers and hospitals and essentially beg for time in their OR. Most often the response is, ‘There’s no availability,’ or ‘We’re closing for the day. Can you do it tomorrow?’ In addition, there’s time-consuming paperwork and other requirements.

“In the past,” Dr. Feistmann says, “I’ve often told my patients, ‘I’m ready to go and you’re ready to go; we just need an operating room that will let us in.’ We work with very good people at our local hospitals and surgery centers. They’ve been very accommodating, and they always try to help us as best they can. But in a lot of ways they’re limited, because surgery centers close in the early afternoon. Hospitals are also trying to close their ORs for the day and be efficient with staff and resources and finances. Dealing with emergencies is seldom profitable.

“For example, before we opened our OR, near the end of construction, we had a 41-year-old radiologist visiting from Texas who had a superior bullous fovea-on retinal detachment,” Dr. Feistmann recalls. “He came in at 7:00 a.m. on a Friday morning, and our clinic was very busy. A radiologist depends entirely on his or her eyes, so potentially losing your vision is very scary; if you’re visually impaired, you’re out of a job. So he was understandably very upset.

“I told him to get on the next flight back to Texas, and that his doctor would be waiting to take him straight to the OR,” Dr. Feistmann continues. “I told him that with a gas bubble in his eye following the surgery, he wouldn’t be able to fly home. However, his vision was getting worse by the hour and he didn’t want to wait until the evening. He said that he’d be willing drive from New York to Texas just to get the surgery done right now.

“Unfortunately, our OR wasn’t finished yet, so I had to call the hospital myself and beg them to squeeze him in,” he recalls. “I knew there was OR time available because my partner happened to be in the OR and had just had a cancelation. However, the anesthesiologist told me there was no OR time available, and the patient would have to wait until the evening. When I asked why my patient couldn’t just take the slot that was opened by the cancelation, he responded that it was ‘hospital policy.’ Clearly the ‘hospital policy’ was meant to disincentivize us from calling them with urgent cases. I had to tell my patient’s story to strike an emotional nerve and convince them to find a slot.

“Fortunately, after an hour of begging and making my other patients wait, my partner was able to operate around noon,” Dr. Feistmann says. “The radiologist was thrilled. He said losing his vision would have impacted his entire family. But if our office-based surgical suite had been available, the surgery would already have been done.”

“We certainly don’t handle emergencies for the money; we do it because it’s part of our responsibility as doctors,” Dr. Feistmann points out. “It’s part of our job. But for businesses, handling emergencies is problematic. It’s not like patients going to an ER, where every visit produces a lot of money. The reimbursement to facilities isn’t sufficient for them to keep staff on for extra hours to manage a retinal emergency. So, our access to these facilities seems to keep shrinking. At the same time, we have more patients and more emergencies to deal with. I found myself wondering how we were going to deal with this for the rest of my career.”

Moving Retinal Surgery In-house

Dr. Feistmann says the obvious answer was to have an in-office surgical suite that he has access to 24/7, 365 days a year. “We took it upon ourselves to research this possibility,” he says. “Surgeons have been doing office-based surgery for about 10 years, so there’s a lot of data out there, including the Kaiser Permanente data1 and data gathered by iOR Partners. Tom Aaberg, MD, in Michigan published a report about doing 30 cases using office-based surgery back in 2014. I’ve also spoken to lots of other surgeons who’ve done it, including Omar R. Shakir, MD, MBA, a retina specialist in Greenwich, Connecticut, who also does cataract surgery. He told me about his experience and made it clear that it can be done and that it’s safe. That gave me the confidence to proceed.”

Dr. Feistmann says their in-office surgical suite opened for business on May 24th of this year. “To date, we’ve repaired 18 fovea-on retinal detachments,” he says. “We’ve been able to start the surgery within two to nine hours after the patient checks into our office, usually closer to four or five hours. On at least a couple of occasions we’ve gotten the patient onto the operating table in less than two hours after being notified that he or she was coming in with an emergency. There’s data that shows the sooner you address a detachment, the better the outcome, so we’re proud of that.

“The beauty of this is that when we get the phone call, there’s zero stress for me or the staff or the patient about when and where we’re going to do the surgery,” he continues. “We tell the patient that we’ll do it right here and we’ll get it done today. Instead of spending time on the phone calling people and begging for a slot, our staff can spend their time and energy taking care of the patient and getting things ready for the surgery. This has been very gratifying for me and the staff. The patients are very happy, and we’ve had excellent outcomes. We’ve done 92 cases to date, and we’ve had no infections, complications or adverse events.”

But what do his patients think? “Patients are very happy to be able to take care of their problem in the office,” he says. “I was expecting some push-back, but apparently our patients have always expected it to be done in the office. So now when I say where the surgery is happening, they say, ‘Great!’ ”

Is Office-based Surgery Safe?

Dr. Melendez says that some people seem to think that in-office surgery is done in an exam room. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” he says. “Our OR is a completely sterile environment. It’s all approved by the same accrediting bodies that approve ASCs.

“We have a sterile operating room next to our LASIK suite,” he explains. “Next to that is a clean-and-dirty room, just like in a surgery center. We use the same equipment, with the same special paint on the walls and floors. It’s a standard operating room that just happens to be at the end of my building. In addition, some of my staff have worked in surgery centers for 25 years, so we know sterile procedure.

“To date we’ve done almost 1,000 surgeries in our office-based surgery suite,” he adds. “We’ve had zero cases of endophthalmitis.”

“When we say we have an office-based operating room, we’re not talking about doing surgery in an exam chair or in an exam room,” notes Dr. Feistmann. “It’s an OR just like the OR in an ASC or hospital, with the same equipment and same sterile procedures. The key difference for us is that it’s connected to our office and we have access to it 24/7. Of course, there are services an ASC or hospital can offer that we can’t, but those resources generally aren’t relevant for ophthalmic surgery.

“Safety is something we’re concerned about at all times,” he notes. “What reassured me going into this was that there’s data on more than 40,000 cases that have been done in an office setting, and that data shows excellent safety. Our track record so far has been excellent as well; although we’ve only done 92 cases, we haven’t had a single instance of endophthalmitis.

“I see a number of reasons for that,” he continues, “including the fact that we follow the same protocols as any other OR, and the reality that we can perform the retinal surgery sooner, which lowers risk and is associated with better outcomes. In addition, I know our staff is very well trained, because I trained them myself. I’m not working with someone new, or someone with no retinal surgery experience, which has happened in ASCs and hospitals. And, I always have the equipment I need, which increases the safety of the surgery.”

What’s Required to Proceed? For surgeons considering taking the plunge into owning their own in-office surgical suite, a big question is what kind of investment in time, money and space is required to make this happen. Daniel S. Durrie, MD, founder of Durrie Vision in Kansas City and chairman at iOR Partners, explains. “Building an ambulatory surgery center for ophthalmology surgery usually costs anywhere from $2.5 to $4 million,” Dr. Durrie says. “You can build an office-based suite with the same OR specifications and equipment for $250,000 to $400,000. In terms of making back your investment, the break-even point for an ASC is 100 to 120 cases per month. In contrast, the break-even for an office-based surgery center is 30 to 35 cases per month. “In terms of the space you’d need in order to set up a basic in-office surgical center, that differs depending on the configuration of the space and your equipment choices,” he continues. “The minimum space is usually between 600 and 1,250 square feet, depending on whether you want one or two ORs. We usually require a minimum of 12 weeks to launch an in-office surgical suite, assuming there are no unusual complicating factors at the location or pandemic-related construction slowdowns. Typically, our launches happen between 12 weeks and six months after signing an agreement. Robert F. Melendez, MD, MBA, the CEO and founder of the Juliette Eye Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, explains that for an in-office surgery center you need an operating room, a clean-and-dirty sterile room and a pre- and postop holding area. “If you need additional rooms for other purposes, you can use your exam rooms, too,” he notes. “That’s what we do. On the day of surgery, the whole clinic is converted to a surgery center. We also have a separate laser suite in which we do LASIK, SMILE and PRK. Right now we set aside two days a week for in-office surgery, but we’ll be moving to two and a half days soon.” “Both an ASC and an in-office surgical suite are great alternatives for an ophthalmologist, but they make the most sense for different styles and sizes of practices,” Dr. Durrie adds. “Generally speaking, an in-office surgical suite is a good option for a practice that can’t build an ASC, perhaps because of insufficient volume, or simply has no access to one. In some states Certificate of Need rules prevent a practice from starting an ASC, and this is a good alternative that isn’t subject to those rules. It also makes sense for many practices that are just starting up.” —CK |

What About Profitability?

Dr. Melendez notes that the financial issues are mixed at the moment. “Our costs are higher when we use the ASC, but the reimbursement is better,” he says. “But CMS is now looking at this and considering changing the ruling about office-based surgery to full payment, as they do for ASCs. If that passes, it will become effective in January of 2024. Then you’ll see a lot more surgeons thinking about building their own office-based surgery suite.”

Dr. Melendez explains that profitability hasn’t been a problem for him because he has a premium-lens-oriented practice. “I believe that most doctors who choose to set up an office-based surgery center are trying to offer a more premium experience for patients,” he says. “That kind of practice tends to have higher rates of conversion to premium lenses such as Panoptix, Vivity or the Light-adjustable Lens. Combine that with the fact that you’re not paying fees to an ASC, and your profitability goes up.

“In addition, we’re saving ourselves and our patients time and providing a far better experience,” he says. “It’s been like night and day for me personally. I used to do 32 cases per day, mostly straight Medicare cases. We had to do high numbers in order to remain profitable. Now I’m doing 12 cases a day, and I have about an 80 percent conversion rate to premium lenses. Today my solution is to do high value, not high volume.”

Dr. Feistmann says he realizes that cost is a big concern for most surgeons. “Many surgeons I talk to like the idea of having an OR in their office, but they’re worried about the cost and reimbursement questions,” he says. “We’ve just started, so although we have a plan, we don’t have a lot of the data about reimbursement yet. But we’ve gone ahead anyway because it’s clearly good for our patients and it eases our stress dramatically when we have to manage an emergency. It’s what I would want if I had an eye emergency, instead of having to wait around with oftentimes unnecessary delays, and maybe not ending up in the best operating environment in a late-night situation. Besides, in-office surgery is clearly within our capabilities, given today’s smaller-gauge instruments and reduced need for systemic IV anesthesia.

“The other thing to remember is that profitability isn’t just a matter of how much we’re paid,” he points out. “It’s also a question of how much time we spend to earn that payment. I think of it as a ratio, where the numerator is the payment and the denominator is the time I spend on the work. My main goal is to shrink the denominator, meaning taking less time to do an emergency case at the hospital, or avoid taking an entire OR day away from office patients just to do a few surgical cases at the surgery center. This way, even if the numerator (payment) decreases slightly, if the denominator (time) decreases even more, proportionally, I’m actually ahead. And if we can figure out a way to increase the numerator while decreasing the denominator, then we’ll be way ahead.

“When I repair a retinal detachment in our office surgical suite, I don’t have to wait around until the OR is free,” he notes. “In the hospital, it’s a huge unknown, and it’s stressful and time-consuming. In many cases five hours go by from the time I leave my office for an after-hours emergency until the time I’m done operating in the hospital. If I do that surgery in my office, it takes one hour of my time. So that difference has to be taken into account as well.

“Because we’ve only recently started doing this, I don’t know what the long-term picture will look like,” he concludes. “But I know for sure that I’m spending far less time on these cases. I’m leaving the office at 5:30 with the case completed, not leaving the hospital at 10:30 at night.”

In-office vs. ASC

“It’s clear that some patients haven’t been happy with the ambulatory surgery center experience, especially during COVID,” says Dr. Melendez. “For example, one advantage of an office-based surgery center is that it’s much less crowded. During COVID, patients have wanted to avoid crowds. Furthermore, patients who’ve had one eye done at an ASC and the other done here tell us it’s an entirely different experience. Overall, patients are much happier having their cataract surgery here when they compare the two experiences.”

Dr. Melendez points out that scheduling is another big advantage when you’re working in your own surgical suite. “We have more control over our schedule, in contrast to an ASC, where you’re somewhat dictated to in terms of scheduling,” he explains. “Patients get in faster. We can move things around. With office-based surgery, if we want to add a surgery in the afternoon, we can.

“I’m sure folks who own ASCs are concerned about losing some of their volume [because of this trend], but there will always be a need for patients to have surgery in an environment where they have access to IV sedation and general anesthesia,” he adds. “Those patients should be done at the surgery center or in a hospital.”

“In your own OR, you have full control over everything,” Dr. Krajnyk points out. “You can pick whatever lenses and instruments you want. The same technicians who see the patient the day of their appointment see them pre and postop, so patients are much more at ease. The fact that everything is under one roof makes them even more comfortable. And I can tell patients that all of the instruments and tools we’re using to do the surgery have been chosen by me, so they’ll have a great experience.

“In contrast, I don’t have as much control in the hospital or ASC,” he says. “I work with a random nurse who doesn’t know me. I don’t even know which phaco machine or instruments they’ll have. The nurse will sometimes give me the wrong instrument; I’ll ask for a Sinskey hook and I’ll get a 20-ga. needle. And if something goes wrong in the middle of a surgery and you need a piece of equipment right away to prevent a complication from happening, you may find that the nurse has no idea where that piece of equipment is.

“Furthermore, if something breaks, you might have to wait six months or a year for the center to fix it,” he continues. “For instance, at a local surgery center they’ve refused to replace a 30-year-old surgeon’s chair that’s uncomfortable and no longer rolls. And the WIFI often doesn’t work, making it impossible for surgical devices to share information digitally. In my office, if my Zeiss Callisto aberrometer can’t get data from my IOLMaster for some reason, I can walk over and get it manually. If that happens in the ASC, it would be a 25-mile drive to get the data.

“We’ve all been taught to worry about what might happen with no anesthesia to fall back on,” he notes. “But the reality is, even in an ASC the anesthesia doesn’t always go well. Here, we just give patients a mild oral sedative. They’re relaxed and calm, but not zonked out or so loopy that they don’t know what’s going on. For both the patient and us, that’s a win.

“Having our own OR impacts how long things take, as well,” he notes. “We can get a cataract patient in and out in less than an hour. If the surgery is done at the hospital or an ASC, it will take at least half a day for the patient.”

Dr. Krajnyk adds the patient experience is much nicer in his practice than at an ASC or hospital. “We have LED lighting on the bottom of the walls, and we play light music for the patient. I ask what they want to listen to and we put their choice on Pandora. Patients sit in a massage chair before and after surgery. They don’t have to fast overnight, because they’re not getting heavy sedation. Their anxiety level goes way down, and they’re much happier with the results.”

|

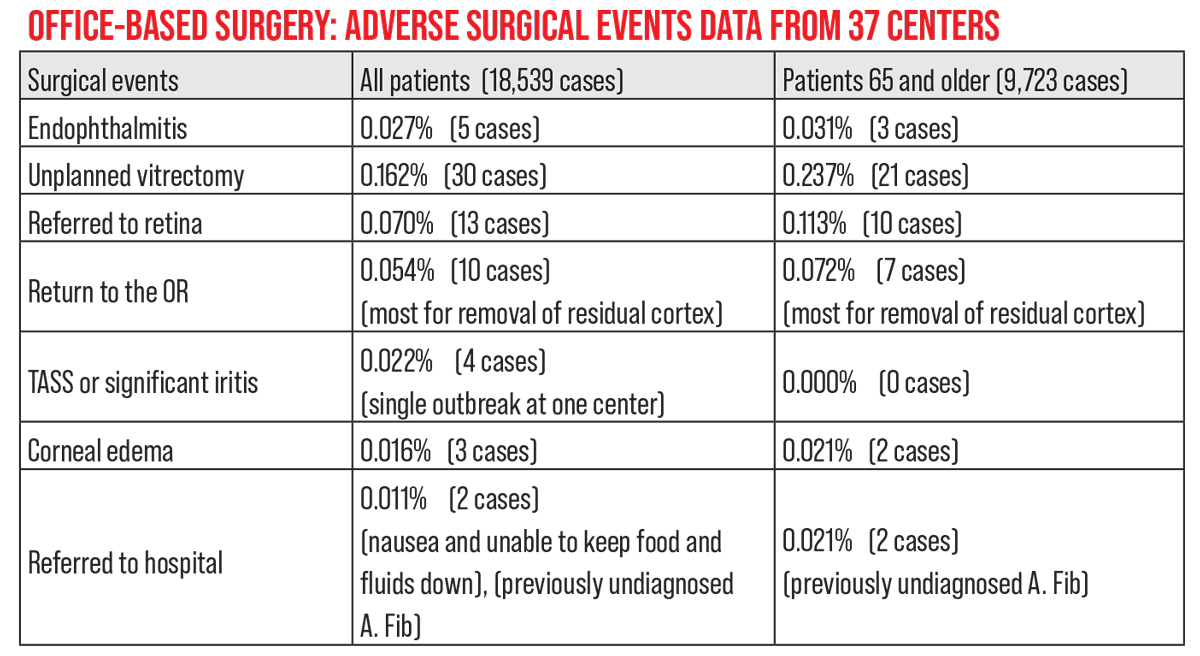

| This represents complete data from 37 centers in which an in-office surgery center was created with help from iOR Partners. Every patient treated in these in-office surgery center was included; the data is collected quarterly as part of each center’s Quality Accreditation Program. The average age of all patients was 64.7 years. |

Who Shouldn’t be Done In-office?

Some surgeons have pointed out that the vast majority of cataract surgery patients have some comorbidity, theoretically making them poor candidates for in-office surgery. However, Dr. Melendez points out that a co-morbidity, by itself, isn’t a reason to avoid office-based surgery. “It’s a person with an uncontrolled comorbidity who shouldn’t have surgery in the office,” he explains. “If your high blood pressure or diabetes is well-controlled, there’s no reason you can’t have office-based surgery. Plenty of patients with stable hypertension or diabetes have had successful surgery in our office-based OR.”

What about claims that up to one- third of cataract patients require anesthesia intervention? “You need to look at that data more carefully,” Dr. Melendez suggests. “What does it mean when someone says they needed intervention? Does it mean that they went from oral to IV sedation? That they needed additional IV sedation? And what patient population was being studied? We haven’t had to do any anesthesia intervention in our surgery center in nearly 1,000 cases.

“We still sometimes send some patients who have poorly controlled comorbidities such as diabetes, high blood pressure, stroke or heart issues to the hospital or a surgery center,” he adds. “Patients who are at high risk should be done in one of those settings. That’s why we’d never say that office-based surgery will replace ASCs; we’re just saying that for most patients it’s a convenient, safe and effective way to do the same surgery that we would do in the surgery center.”

What about anesthesia? Jonathan Feistmann, MD, a retina specialist practicing at NYC Retina in New York City, notes that you can arrange to be able to offer full anesthesia in an office surgical suite. “I know surgeons in some other specialties with in-office ORs who can put patients under general anesthesia,” he says. “The reason many don’t offer that option—and even some ASCs don’t offer it—is because it isn’t necessary very often. If you only need this a handful of times during the year, it’s not worth all of the things you have to do to make it safe and feasible in this setting. It makes more sense to go to the hospital for those few cases in which it’s needed. “We discussed being able to do general anesthesia in our OR when we were first planning it,” he continues. “We decided it wasn’t worth the significant amount of effort to make that possible, given that such cases only come up a few times a year. We wanted to build something that could handle the cases that come up on a weekly basis. “The key, in our experience, is to make it a painless surgery,” he adds. “If it’s painless, the patients tolerate the surgery very well without the need for systemic anesthesia. We have some patients that require valium prior to surgery, or an MKO melt during surgery for anxiety, but many only need good local anesthesia and reassurance. “Most office-based surgery centers offer Class A and B anesthesia, which refers to oral and IV sedation,” says Robert F. Melendez, MD, MBA, the CEO and founder of the Juliette Eye Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “What a given office-based surgery suite offers depends on their needs and what types of patients they’re going to treat. Here, we do oral sedation instead of an IV, and patients find that to be a big relief. We were planning to offer Class B anesthesia as well, but we literally haven’t had to do it. If we can see that the patient will need IV sedation, or it’s a more complicated case, then we recommend doing the case in the ASC. Generally, I think that’s safer for the patient.” —CK |

“We follow the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s guidelines for ambulatory surgery center or hospital admission,” Dr. Krajnyk says. “For example, if their blood pressure isn’t appropriate, we make them go to their primary doctor or cardiologist to make sure it’s under control and ask for clearance for low-risk cataract surgery. If the patient’s blood pressure and heart rate are stable, we’ll proceed. But if the patient is very frail or fragile, or they’re shaking and need general anesthesia, those are patients we take to the ASC and do under general anesthesia. If the patient has recently had bypass surgery or something like that, we’d just wait four to six months and get cardiac clearance. However, these patients are few and far between.

“People say, ‘What happens if there’s a medical complication?’ The same thing that happens in an ASC,” he continues. “You do high-quality CPR, call 911 and the patient is whisked away to a hospital. There’s no difference. In reality, anything can happen to anyone at any time. You can walk down the street and get an aneurism. When a colleague asks about this, I ask how many of their patients have had a heart attack on the table. How many have died? Everyone I’ve ever asked has said ‘None.’

“Knowing which patients wouldn’t be good candidates isn’t as mind-boggling as some people make it sound,” he says. “It’s no different from 25 years ago when ASCs were starting up. Our patients are generally healthy, and we do a preop evaluation. We check the blood pressure, heart rate, all the things an ASC would do. The protocols are the same.

|

“For example, one patient drove here from Colorado to have his cataract surgery because his friend had recommended us,” he recalls. “On the day of surgery he walked in as if nothing was wrong. He looked fine, said he’d just been in the pool that morning. However, his blood pressure was 190 over 140 with a heart rate of 145. We explained that he was a walking time bomb—he could have died any day! So we had him go to urgent care to get this addressed. At the hospital, they put him on three or four medications. A week later he was cleared for the surgery and we did both eyes. Back in Colorado he visited a cardiologist and is doing very well.

“The point is that we’re just as capable of catching these things as any other surgery center would be,” he says. “They would have done the same thing we did. We have a crash cart with a defibrillator, and everything we need to stabilize a patient, but we haven’t actually needed to use it.

“I understand the concern about patient comorbidities,” he concludes. “However, if your patient has a comorbidity, you’d want the patient to be more relaxed and comfortable, because that comorbidity will be less of an issue if the patient isn’t nervous and anxious. It’s good to give them less sedation and have them be more comfortable and happier, without an IV. In fact, more complications result from anesthesia than from cataract surgery.”

The Big Picture

“In a hypothetical world, I think if every retina specialist had an operating room in their office, we’d be able to take care of our emergency cases much more easily and quickly,” Dr. Feistmann says. “Some people point out that we can’t take care of every single patient inside the office, and that’s true. But an office-based operating room isn’t meant to replace the hospital or ASC; it’s meant to add to the tools we have available to us as surgeons.

“At the same time, we’ve found that we can take care of most emergencies here, far more of them than we anticipated, and we can do so more effectively, comfortably and safely than we expected,” he continues. “Although it’s only been a short period of time and a small number of patients so far, I’d say that most of the emergency cases we’ve dealt with have been treatable here in the office surgical suite. For example, the vast majority of my fovea-on retinal detachments have been successfully, safely and comfortably treated in the office. And feedback from the patients about doing the surgery this way has been excellent.

“We’ve only been using our in-office surgical suite for a short period of time and with a small number of patients, so we’re still going very slowly and deliberately,” he says. “We’re gathering a lot of data, sharing our data with others and working hard to do everything safely. Meanwhile, we still operate in hospitals and surgery centers when the patient’s situation requires it.

“We’ve been pleasantly surprised by a lot of things about this new situation,” he adds. “I’m not suggesting that everyone should do this; everyone should do whatever they think is good for their patients. But for us, this has been excellent so far.”

“I don’t think there could be a better time to consider doing this,” adds Dr. Krajnyk. “As we speak, CMS is in negotiations to come up with an approval code for in-office cataract surgery, as well as some glaucoma and retina surgeries.”

“This isn’t just the wave of the future,” says Dr. Melendez. “It’s happening now.”

Dr. Melendez consults for Alcon, Zeiss, Allergan, Ocular Sciences and RxSight. He reports no financial ties to iOR Partners. Dr. Krajnyk owns shares of iOR Partners. Dr. Durrie is chairman at iOR Partners. Dr. Feistmann reports no relevant financial ties.

1. Ianchulev T, Litoff D, Ellinger D, Stiverson K, Packer M. Office-based cataract surgery: Population health outcomes study of more than 21,000 cases in the United States. Ophthalmology 2016;123:4:723-8.