It’s an unfortunate reality that topical treatment of glaucoma often leads to—or worsens—ocular surface disease. Studies suggest that anywhere from 40 to 59 percent of glaucoma patients suffer from OSD,1,2 a far greater percentage than is found in the general age-equivalent population. This phenomenon has been studied for decades, so it’s well-understood, but it’s not something that clinicians tend to focus on when seeing patients in the clinic. Here, I’d like to talk about this concern and suggest some ways we as clinicians can minimize the problem.

Anytime you put a topical therapy on the eye, you’ll find changes on the ocular surface that may include tear-film disruption with increased tear breakup time and loss of conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells. To a large extent, this problem can be attributed to the preservative benzalkonium chloride. BAK has detergent properties that disrupt the cellular membranes of bacterial contaminants in multidose containers; but those same properties can trigger apoptosis in epithelial cells of the cornea and conjunctiva, cause chronic inflammation and disrupt the tear film.3,4

Unfortunately, BAK isn’t the only problem. OSD can be a problem even if a medication is preservative-free, because negative changes can also be triggered by active ingredients. Either way, for the patient OSD manifests as foreign body sensation, the feeling of dry eyes and blurriness of vision—symptoms that usually do not escape the patient’s notice.

Don’t Overlook the Signs

To avoid unintentionally adding to the patient’s burden, a couple of key strategies are helpful.

First, don’t fall into the trap of ignoring the problem. When a patient comes into the clinic and we perform a typical glaucoma exam, our tendency is to focus on the disease of presentation: What is the IOP? What does the nerve look like? What’s the condition of the retinal nerve fiber layer? We usually pay less attention to the ocular surface and any related complaints the patient might have, such as blurry vision or foreign body sensation. So the first thing to do is move these issues higher on our priority list.

|

Second, be sure to check your glaucoma patients for signs and symptoms of dry eye. Left untreated, problems with the tear film can leave the cornea open to epithelial damage from multiple sources, including the environment.

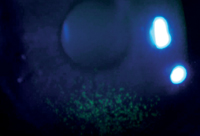

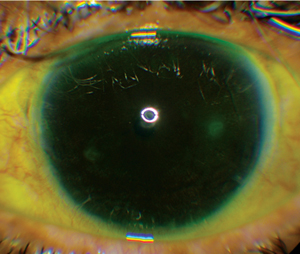

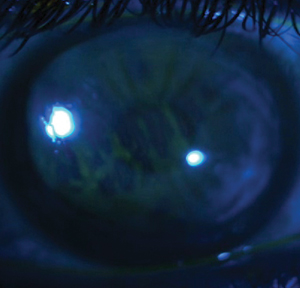

Many clinicians are concerned that checking for dry eye will take up too much time, but it’s possible to do an ocular surface evaluation as part of your normal examination, even in a busy glaucoma clinic. The easiest thing to do is to check the tear-film breakup time using the fluorescein that you instill for the pressure check. (Monitoring TFBUT with fluorescein reportedly produces high specificity and about 85-percent accuracy.5) Also, look for signs of trouble such as punctate epithelial erosions on the conjunctiva or cornea. In addition, spend a few seconds looking at the lid margin for signs of meibomian gland dysfunction. Taking these steps only requires a few extra seconds, and as long as you use the same protocol each time you see the patient it adds value to your exam.

Third, be on the lookout for OSD in new patients. If a patient comes in at baseline with OSD, whether mild, moderate or severe, that should be a red flag. If you take somebody with existing OSD and place her on a BAK-containing medication, whether it’s once, twice or three times a day dosing, at some point the active ingredient and/or the preservative will exacerbate the disease. These individuals are likely to end up with more severe OSD that will affect their daily activities and quality of life. When we realize that a patient we’re about to treat has existing OSD, that’s the time to seriously consider prescribing a medication with a preservative other than BAK, or no preservative at all.

In this situation, I discuss the problem with the patient; we talk about trying to restore the tear film and the ocular surface. Sometimes I’ll get my cornea colleagues involved at the outset. For these patients I consider options such as preservative-free artificial tears and a short course of steroids to reduce inflammation, along with having a discussion with the patient about the possibility of trying laser trabeculoplasty instead of topical medications.

Addressing the Problem

Once you’ve identified that a glaucoma patient’s ocular surface is showing signs of trouble, there are two approaches you can take: To address the disease, you can either add to the therapy or subtract from it.

The additive approach would mean keeping the patient on all of the current medications while adding any of several treatments. You could have the patient use artificial tears— preserved or preservative-free. If meibomian gland dysfunction is part of the problem, you could have the patient start using warm compresses and lid scrubs. You could also insert punctal plugs. The downside of the additive approach is that all of these options address the OSD from a tear-film standpoint, but don’t really address the root cause of the problem—the impact of the active ingredient and preservatives (if any) that are in the medication.

|

Given the aforementioned options, why not just start by treating with a preservative-free formulation? The answer may be partly that we’re all creatures of habit (both physicians and patients), but there are other issues involved. For example, Zioptan and Cosopt Preservative Free both come in unit doses, a format that’s unfamiliar to a lot of glaucoma specialists from a therapy standpoint, even though we’ve been using unit doses of artificial tears and Restasis for many years. Using single dose packaging is also quite different from the patient’s perspective; it’s not yet clear whether patients will favor this approach over multidose bottles. And there is the issue of access to insurance programs, as well as the co-pay cost when the patient picks up the medication at the pharmacy.

Another reality is that eliminating the preservative doesn’t totally get us off the hook for OSD issues because the active ingredient may also be problematic. The entire class of prostaglandin analogues is associated with hyperemia—redness of the eye that occurs because of vascular dilation and slight leaking from the vessels in the conjunctiva. Other medications like the alpha-agonists, including Alphagan, are associated with higher rates of redness and allergic reaction compared to some of the other medication classes. Other groups, such as beta blockers or carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, may also produce a hyperemic response, although probably to a lesser degree. The reality is that these compounds are not naturally meant to be on the eye, so they can all cause some level of ocular surface problems.

However, I think it’s safe to say that most of the corneal problems we see, such as epithelial cell loss, are secondary to the preservative. So if a patient has mild OSD, and is pushed to moderate or severe surface disease by a given medication that has a detergent preservative such as BAK, you can probably take the patient back to a mild level of disease by moving him back to a preservative-free medication. You may not get him back to the level where he’d be if nothing were being put on the eye, because he’s still going to have some measure of reaction to the active ingredient. But eliminating the BAK should make a positive difference.

Perhaps the best argument against automatically starting every glaucoma patient on a preservative-free medication is that most patients will do just as well with preserved medications. If a patient diagnosed with glaucoma has a normal ocular surface and no tear-film dysfunction, in my opinion any of the glaucoma medications that are available for use will do very well.

Non-pharmaceutical Options

It’s also true that some patients will be good candidates for the option of switching from topical drops to an alternate treatment such as laser trabeculoplasty; that’s certainly one way to eliminate the ocular surface concerns associated with drops. This should be high on the list of alternatives to consider, especially in patients who are using multiple medications, where reducing the number of drops is not a promising option because of the need for more aggressive therapy.

The typical algorithm for managing a glaucoma patient in the United States and abroad is to start the patient on medical therapy and escalate it, if necessary, from one drop to two or three drops before considering trabeculoplasty. In my practice, I typically start patients on topical therapy, but we usually discuss the option of trabeculoplasty before we initiate any topical medications. Furthermore, I very rarely prescribe more than two topical medications for a given patient before having a more in-depth discussion about trabeculoplasty. My main concern is that adherence is decreased when the patient goes to two medications, and even more so if I consider a third medication. In essence, you’re getting diminishing returns from each medication you add. So when more treatment is required, laser trabeculoplasty has advantages over additional drops.

If we’ve tried trabeculoplasty but the pressure still hasn’t come down sufficiently, the third option is invasive surgery. This is something that, in its current form, I reserve for more advanced disease. That’s primarily because of the risk/benefit ratio created by the efficacy of surgery’s IOP lowering vs. the likelihood of complications from the surgery.

|

One last thought: If a patient is having issues with topical application causing or worsening OSD, and trabeculectomy has become necessary, I would advise the surgeon to do two things. First, try to lessen the load of medication for two to four weeks before the surgery. Second, place the patient on a mild steroid that will quiet down the conjunctiva and restore the tear film before the surgery. This makes the surgery more likely to be successful because you’re decreasing the inflammatory and scarring response that can occur post-trabeculectomy.

Patient Instillation Problems

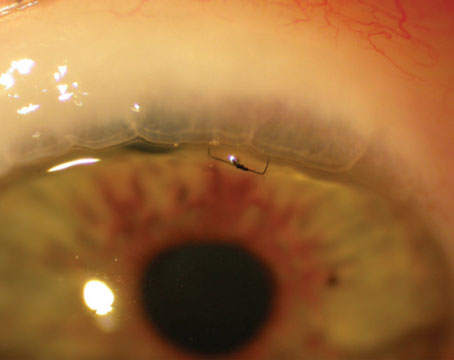

Another way the ocular surface can be impacted by the use of topical medications is via patients scraping or pressing the tip of the eye-drop bottle against the cornea. We’ve all seen a patient who has a perfectly circular abrasion on the cornea that matches the bottle opening. (For example, see the photograph on p. 47.) Patients with low vision or elderly patients who have physical limitations have a very difficult time getting their drops in; sometimes feeling the bottle on the eye reassures them that the drop is actually going onto the eye.

The primary way to avoid this is patient education. In our clinic, when we’re starting topical therapy, we have an artificial tear bottle handy so patients can be instructed in the use of eye drops and be observed when they’re instilling them. I also ask all of my ongoing patients to bring their drops in at every visit so we can review them, and so I can review the patient’s technique if I suspect that a patient is having trouble getting them in.

The point is to actually observe the patient instead of simply assuming there’s no problem. It doesn’t take long to do, and watching the patient instill drops allows me to identify multiple problems with technique, including the potential for injury when the bottle gets too close to the eye. I find this very helpful in terms of preventing damage to the ocular surface and ensuring the effectiveness of the drops, and I think the patients appreciate it as well.

Going the Extra Mile

Given that our first priority as physicians is to do no harm, it’s worth making a real effort to prevent ocular surface disease from becoming a problem—or a worse problem—for our patients. If you employ some of the strategies described above, both you and your glaucoma patients should reap the benefits. REVIEW

Dr. Kahook is a professor of ophthalmology and director of clinical and translational research at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver. He has been a consultant to Alcon Laboratories, Merck, B&L, Glaukos, Ivantis, Clarvista Medical and Allergan, and has received research support from Alcon, Allergan, Merck, Genentech, Regeneron, Clarvista Medical, AMO, Glaukos and the State of Colorado. He has intellectual property interests with AMO, ShapeTech, ShapeOphthalmics, Dose Medical, Glaukos and Clarvista Medical.

1. Fechtner R, Budenz, D, Godfrey D. Prevalence of ocular surface disease symptoms in glaucoma patients on IOP-lowering medications. Poster presented at the 18th Annual Meeting of the American Glaucoma Society; March 8, 2006; Washington, DC.

2. Noecker R. Effects of common ophthalmic preservatives on ocular health. Adv Ther 2001;18:5:205-215.

3. Noecker RJ, Herrygers LA, Anwaruddin R. Corneal and conjunctival changes caused by commonly used glaucoma medications. Cornea 2004;23:5:490-496.

4. Kahook MY, Noecker RJ. Comparison of corneal and conjunctival changes after dosing of travoprost preserved with Sofzia, latanoprost with 0.02% benzalkonium chloride, and preservative-free artificial tears. Cornea 2008;27:3:339-343.

5. 2007 Report of the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS). Ocul Surf 2007;5:2;65-199.