Today’s MIGS

For the purposes of this article, MIGS will be defined as a Food and Drug Administration-approved, minimally invasive, ab interno procedure that is performed through a small incision, usually corneal, that spares the conjunctiva. The procedure is aimed at decreasing intraocular pressure in mild to moderate glaucoma patients. Here are the general ophthalmologist’s current MIGS options:

• iStent. The Glaukos iStent is the most recent addition to the minimally invasive armamentarium, having just been approved for use in the United States in 2012. It’s an extremely small titanium device implanted into Schlemm’s canal during cataract surgery in patients with open-angle glaucoma who could benefit from IOP lowering below that normally associated with cataract surgery. The iStent comes preloaded in an inserter.

|

“Work by Richard Lindstrom and Tom Samuelson showed that cataract surgery alone could decrease IOP by at least a couple of points,” says Jason Bacharach, MD, director of glaucoma clinics at Cal Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. “So, with the addition of a MIGS procedure, it might be possible to expand the number of patients that a cataract surgeon could treat in his practice by being able to control the IOP at the same time he’s taking out the cataract, as well as potentially reduce the number of medications the patient is using postop.”

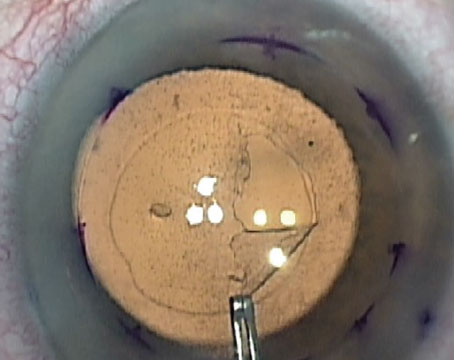

• Trabectome. The NeoMedix Trabectome uses bipolar cautery on a disposable handpiece, inserted into the anterior chamber through a clear corneal incision, to ablate a certain number of clock hours of trabecular meshwork to increase aqueous outflow. The handpiece is equipped with irrigation and aspiration ports.

Brian Francis, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of California’s Keck School of Medicine/Doheny Eye Institute, says that the pressure-lowering potential of the Trabectome depends on where the patient starts. “It will generally get the patient into the mid-teens,” he avers. “If the patient is at 30 mmHg preop, for example, he will get to the mid-teens. If he’s already at 16 mmHg but is on two or three medications, he may stay at 16 but be able to get off of one or more of the medications.”

• Endocyclophotocoagulation. The Endo Optiks ECP system uses a laser and an endoscopic viewing system, inserted through either a corneal or limbal incision when combined with cataract surgery, or a limbal or pars plana incision when done alone, to ablate the ciliary processes and reduce aqueous production.

In a retrospective study, researchers in the United Kingdom reviewed 58 cases of ECP combined with cataract surgery that were followed for two years. They report that the average preop IOP of 21.54 mmHg was reduced to 14.44 mmHg at two years. The mean decrease from baseline to 18 and 24 months was 7.1 mmHg, and there was a statistically significant decrease in IOP at all time points.1

Dr. Francis says one of the benefits of ECP is flexibility. “For Trabectome and iStent, you need to have an open angle, but since ECP isn’t trying to enhance aqueous outflow, you’re not concerned whether the angle is closed or not,” he says.

Complications

One of the purported strong suits of MIGS procedures is their safety. Here’s what surgeons have to say about adverse events and how to avoid them.

• iStent. In 160 eyes in the FDA study (112 from the randomized and 48 from the non-randomized treatment groups), there were 23 intraoperative complications related to implanting the stent, the most frequent of which was touching the iris with the device (11 eyes, 7 percent), failure to implant (three eyes, 2 percent), contacting the endothelium (two eyes, 1 percent) and stent malposition (two eyes, 1 percent). Postop, there were 12 cases of adverse events related to the stent, composed of seven cases of stent obstruction and five of stent malposition.

To prevent failure to implant the stent, Steven Vold, MD, of Fayetteville, Ark., says it’s key to keep the tip of the inserter up. “When you take the insertion device out of the packaging, you have to keep the tip up,” he says. “If you’re not careful you can hit it on the edge of the packaging or something and you can knock it off. I’m also careful not to hit it on the corneal wound during insertion. Since these devices cost about $1,000 each, you don’t want to drop one.”

To avoid malpositioning, Dr. Vold says it’s important to know the anatomy. “A lot of comprehensive ophthalmologists have never done angle surgery before and maybe don’t do gonioscopy in the clinic, so they really need to practice their gonioscopy,” he says. “They should do little things, like learn the corneal wedge technique to know which pigment line is the trabecular meshwork. Also, in the OR, for patients with a little shallower anterior chamber, removal of the cataract before you put the stent in can also be helpful because it’ll deepen the anterior chamber.” Postop, Dr. Vold says you have to look out for the infrequent case of the stent being occluded by iris or pigment. He adds that there have been anecdotal reports of stents coming loose in the anterior chamber, but he hasn’t experienced that. “You just want to make sure they’re in place,” he says. “If I was concerned about it moving around the anterior chamber I’d just go in and remove it.”

|

Dr. Francis says to avoid problems intraoperatively, it’s important to always maintain a clear view. “You want to place the handpiece where you have a clear view and not try to go off to the side where you’re not sure that you’re actually in Schlemm’s canal,” he says. “If you try to push the treatment to the extreme edges you could damage other ocular tissues.”

• ECP. Fairfield, Conn., surgeon Robert Noecker says that IOP spikes are the most common adverse event after ECP, so he focuses on prophylaxis. “For all these patients, I’ll give them Diamox and Alphagan postoperatively,” he says. “The other risk that we worry about when doing ECP is ocular inflammation above that of regular cataract surgery. So I treat inflammation very aggressively. I give them intravenous steroids at the time of the procedure as well as intraocular steroids, and treat them topically a little more aggressively for the first week. If we get them through that first week, the inflammation won’t be a problem.”

Hurdles to Clear

While the current MIGS procedures offer the comprehensive ophthalmologist attractive, low-risk options, but there are still some obstacles to widespread adoption that may be keeping surgeons from committing to them.

Though the Trabectome and the ECP unit can be used by themselves or in conjunction with cataract surgery, they involve a capital expenditure for the equipment that surgeons may not be ready to make. “Any time you have a capital expenditure, that can be a roadblock,” says Dr. Francis. “Surgeons also have to learn a new procedure, which takes an investment of time. If you’re a busy cataract surgeon, learning something from scratch can be daunting. But I think it’s important for surgeons to keep challenging themselves, pushing themselves.”

Regarding Trabectome, on an operative report it is described as “trabeculotomy ab interno, but Kevin Corcoran, a consultant whose firm specializes in reimbursement and coding, notes that there is no CPT code with the description “trabeculotomy ab interno.” He adds that a well-informed biller would probably choose CPT 65820 (goniotomy) although, he says, “It’s apparent that some billers unfamiliar with Latin nomenclature choose CPT 65850 (trabeculotomy ab externo) instead.” Alternately, he notes, some billers might choose a miscellaneous code (66999) although he says the administrative hassles with these codes are well-known. He adds that experts acknowledge that coding for this procedure is not crystal clear, and a new code for trabeculectomy ab interno is probably needed.

The obstacles to widespread iStent adoption revolve around its labeling and reimbursement, which limit surgeons from using it on a wider variety of patients. “Right now we only do it in Medicare patients,” says Dr. Noecker. “Commercial payors and Medicaid have not been paying for it regularly, though once in a while we can get one through, so that restricts your patient population. The other thing is it’s only indicated for the code 36511, primary open-angle glaucoma, so if the patient has any other type of glaucoma, it’s not covered. And it can only be done in conjunction with cataract surgery; it won’t get reimbursed as a stand-alone procedure. Also, it can only be for mild or moderate patients, so if a patient is coded as having severe glaucoma he doesn’t qualify for payment. In addition, you can only put in one iStent.”

In terms of payment, Mr. Corcoran says that the 2013 Medicare iStent reimbursement rate for the facility is $2,978 for a hospital outpatient department and $1,671 for an ambulatory surgery center. “The physician’s reimbursement is variable because there’s no specific value assigned to the CPT code 0191T in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule,” he says. “Various Medicare Administrative Contractors have allowed $252 to $1,235. The average is around $850.”

Another issue, which Dr. Noecker alluded to, is the movement to use more than one iStent in the belief that this will yield better results. “I think many patients do need multiple stents, but right now it’s only approved for one stent,” says Dr. Vold. Also, the way reimbursement is structured, if a surgeon were to implant an additional stent, it would cost the facility more than it would make from reimbursement, so it wouldn’t make sense to do it. As far as FDA is concerned, implantation of two or more iStents concurrently hasn’t been studied in a clinical trial, so an investigational or experimental procedure is almost always not covered by Medicare or other third-party payers, though there are exceptions like Avastin for wet AMD. Mr. Corcoran says that, until more studies are completed, it’s best to stick with the present directions for use.

With all the activity in the MIGS arena, Dr. Noecker thinks the comprehensive ophthalmologist will have no shortage of options. “Though the efficacy of MIGS procedures isn’t as good as trabeculectomy, their risk is lower,” he says, “I think this space will just continue to grow. And the nice thing about these procedures is you might still be able to do a trabeculectomy afterward.” REVIEW

Dr. Noecker was an investigator for Glaukos’ FDA study and is on the medical advisory board of Endo Optiks; Dr. Francis is a consultant to NeoMedix and is on the advisory board of Endo Optiks; and Dr. Bacharach is a consultant to Glaukos. Dr. Vold is a consultant to Glaukos and NeoMedix.

1. Lindfield D. Phaco–ECP: Combined endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and cataract surgery to augment medical control of glaucoma. BMJ Open 2012 http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/3/e000578.full. Accessed 5/14/2013.

2. Francis BA, Minckler D, Dustin L, et al. Combined cataract extraction and trabeculotomy by the internal approach for coexisting cataract and open-angle glaucoma: Initial results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:7:1096-103.

3. Ahuja Y, Malihi M, Sit AJ. Delayed-onset symptomatic hyphema after ab interno trabeculotomy surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;

154:3:476-480.