Microincision surgery has become the Holy Grail among cataract surgeons in recent years. In fact, it's been the impetus behind the mounting interest in microincision phacoemulsification. Yet, most ophthalmologists are far from having all the pieces of the puzzle in place to perform true micro phaco and for the majority of physicians to adopt it as their technique of choice.

In this article, ophthalmologists discuss the driving forces behind the growing interest in micro phaco, what's hindering its widespread acceptance and when it will likely gain broader use.

Driving the Trend

A number of factors continue to fuel interest:

• The desire for less invasive surgery. "The smaller incision is closer to the ideal cataract surgery we all have on our minds, where we're working in a totally closed system," says Mark Packer, MD, clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Oregon Health & Science University in Eugene, Ore. "We want to cause the least morbidity and violate tissues as little as possible. So the smaller the incision you make and the less traumatic the surgery, the better the outcome will be. That is the impetus behind micro phaco," he says.

• New IOL designs. New lens introductions in Europe designed to fit through 1.2- to 1.4-mm incisions and the possible development of injectable implants are encouraging ophthalmologists to develop surgical techniques to be able to remove cataracts and insert implants through these tiny incisions. "If you have a lens that can go through a sub 2-mm incision, you've got to come up with a technique to remove the cataract through that sub 2-mm incision," says Stephen S. Lane, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. And micro phaco will allow ophthalmologists to achieve this, he says.

Nick Mamalis, MD, professor of ophthalmology at John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, says, "The micro phaco techniques being developed are the necessary stepping stones to the ultimate goal of developing [small-incision] IOLs."

|

|

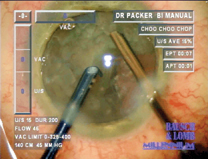

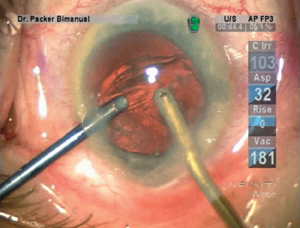

| Left: A moderately dense cataract is extracted using microincision phacoemulsification. Right: Cortical material is washed out of the capsular bag and swept into the phaco tip for greater irrigation and aspiration efficiency. | |

• Cold phaco. Ophthalmic equipment manufacturers, who want their cataract-removal systems to be compatible with microincision surgery, are developing and refining the concept of cold phaco to eliminate the risk of wound burns, a real concern when performing micro phaco. "The advances in phaco equipment have allowed the use of high-frequency pulse and microburst modes that enable us to work with a cooler phaco tip," says Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, adjunct professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, and founder and managing partner of Minnesota Eye Consultants in Minneapolis.

"While the phaco tip isn't actually cold, the term [cold phaco] conveys that incisional heat is reduced to below the threshold for thermal injury," says David F. Chang, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, San Francisco. "The beauty of hyperpulse ultrasound is that we are still able to emulsify the most brunescent nuclei," he says.

• Technique flexibility. Some surgeons favor micro phaco over the coaxial technique because it gives them the ability to use two hands, affording them the flexibility to remove cortex more easily. "When we remove cortex coaxially, we go in with aspiration and irrigation that comes from the same handpiece," says Dr. Mamalis. "And sometimes it's difficult to get to some of the cortex that's subincisional. With the bimanual technique, you have your irrigation in one hand and your aspiration in the other. So if you have some cortex underneath your aspiration tip, you can switch hands and easily remove it," he says.

Another advantage is the ability to use the stream of irrigation fluid from the irrigating chopper as an instrument in the eye, says Dr. Packer. "Rather than reaching down into the capsule to remove epinucleus or reposition a segment of endonucleus, it's possible to use that stream, especially with an open-ended irrigator, to reposition material. If lens material gets caught in the angle, you can atraumatically use your fluid stream to wash it out rather than use another instrument," he says.

|

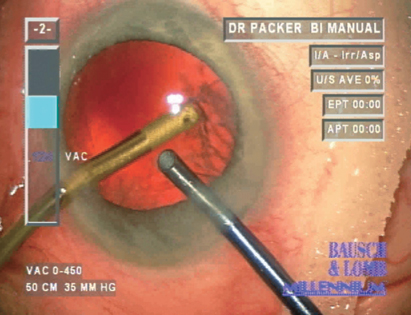

| Strands of hard-to-reach cortex are easily removed with a bimanual approach during irrigation and aspiration without risking injury to the posterior capsule. |

• Patient comfort. Physicians also speculate that microincisions won't create irregular or elevated wounds that can cause foreign-body sensations that patients often complain about. "First day postop, patients often feel like there's an eyelash in their eye right in the area of the incision," says Dr. Mamalis. "So, theoretically, with the 1.5-mm incision there's less of a chance the patient will experience that sensation," he says.

If Not Now, When?

Depending on whom you ask, the instrumentation needed to perform micro phaco effectively and safely is available now.

Yet, most physicians are sitting on the sidelines, refusing to test the waters for a number of reasons. Micro phaco is difficult to learn for the average cataract surgeon, for it requires two hands instead of one, and often, ambidexterity. The learning curve increases the risk for postop complications. There's no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved intraocular lens designed to fit through a 1.2- to 1.5-mm incision in the United States, and there may not be for several years. Presently, cataract surgeons performing micro phaco have to enlarge these microincisions anyway to fit the current lenses inside the eye, which Dr. Lane says, defeats some of the purpose of the procedure and jeopardizes wound construction and stability.

"The average time line for a new lens implant through the FDA is five years," says Dr. Lindstrom. "So that means if [a company] started tomorrow in clinical trial with a sub 2-mm implant, the soonest we could have it would be in 2009. So we have a long way to go. Cataract surgeons shouldn't feel any urgency to perform micro phaco," he says.

According to Robert H. Osher, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati, and medical director emeritus at the Cincinnati Eye Institute, once a high-quality lens is developed to go through a 1.5-mm incision ophthalmologists will begin making the transition from coaxial to micro phaco. "And when we have a superior lens to fit through a 1.2- to 1.5-mm incision, then micro phaco will become the standard of care," he says.

The Other Missing Pieces

Aside from the absence of an appropriate IOL, surgeons are waiting for new handpiece designs that are more compatible with microincision surgery. "The [current] phaco tips and infusion chopper devices have rigid round tubes that, when placed into the smaller incisions, cause distortion," says Samuel Masket, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Jules Stein Eye Institute in Los Angeles. "To prevent distortion, you can enlarge the incisions, but that can cause wound leakage and the chamber to shallow. If you don't enlarge the incision, you'll stretch it and cause it to lose its self-sealing character. The silicone sleeve that goes over the phaco tip during 3.0-mm phaco surgery prevents tissue distortion and leakage because it fills the space," he says.

"Surgeons must think about how they want to design instrumentation for micro phaco. Instead of taking the existing instruments and deconstructing them, we need to start from ground zero to come up with different concepts," he adds.

Dr. Lane agrees that improvements are needed in order for micro phaco to gain wider acceptance. "Cataract-removal techniques and technology are in constant evolution," he says. "This is not the end or even the middle of the story. This is really the beginning. There will be improvements in the handpieces such as the chopping instruments, which need to deliver fluid in a more controlled way than what we're used to right now. And this all has to be done to place a lens through a sub 2-mm incision. It all fits together," he says.

Surgeons who prefer micro phaco are working with equipment manufacturers to develop irrigating choppers with adequate infusion rates to maintain the anterior chamber throughout the surgery. They want them less bulky and awkward to handle to facilitate the procedure, says Dr. Lindstrom.

| Microincisions vs. IOL Design |

| No matter how much cataract surgeons want to perfect micro phaco, they say that the desire to further reduce incision size shouldn't take precedence over the efficacy and integrity of the intraocular lens. "We really can't move on to a technology that decreases incision size to place an implant into an eye that is not just as good as the lenses we're now placing through slightly larger incisions," says Stephen S. Lane, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. "The materials, the biocompatibility, the ease of handling, the injector system and the stability of the lens can't be compromised just for the sole purpose of placing it through a smaller incision," he says. Others agree: "We can't allow a trade-off between lens quality and our ability to do micro phacoemulsification," says Robert H. Osher, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati, and medical director emeritus at the Cincinnati Eye Institute. "For example we're currently investigating lenses that are pseudo-accommodating, light-adjustable, that block blue light for macular protection, that provide contrast sensitivity, that retard PCO and lenses for the presbyope. So we need to make sure that a small-incision IOL is at least as good as these for our patients." According to David F. Chang, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, San Francisco, "If any of these promising lens technologies prove to be superior, we'll want to use them regardless of what incision size is required, because the long-term benefits of the IOL will far outweigh any inconvenience regarding incision size." "So the future of lens replacement surgery," says Dr. Chang, "will be driven more by improvements in IOL optics than the size of the incision. The IOL optic is what the patient will be left with for the rest of his or her life. We won't want to sacrifice performance for the short-term advantages of a slightly smaller incision," he says. "Nonetheless, some very promising lens technologies also appear to be compatible with microincisions." What's certain, says Dr. Lane, is that technology isn't going to stand still. It will continue to evolve. "It's naïve to think that future IOL technologies won't be just as good, or better, than what we have right now and allow the capability of placing the lenses through microincisions smaller than 2 mm for the benefit of our patients." |

Then there's the issue of surgeons having to learn and understand the various temperature safety parameters of the phaco machines to perform the procedure safely and effectively. "No one should leap into micro phaco before understanding the safety parameters," warns Dr. Osher. "Surgeons have to understand the way thermal risks are minimized by all of the new machines. The same applies to the control and removal of nuclear chips with smaller phaco tips. We need to knowledgeably select incision size, the power, the duty cycle, the vacuum, the bottle height, the infusion pressure, the pulses, the viscoelastics and phaco tip design," he says. "Once the research and development is done on this new procedure and there's better instrumentation, and we have a small-incision lens then I think you'll see more surgeons making the transition from coaxial to micro phaco, but not until then."

Don't Feel Pressured

If you're not performing micro phaco on your patients currently, don't feel guilty or pressured to do so, say ophthalmologists. "True micro phaco is still not ready for prime time," says Dr. Lane. For the most part, micro phaco has piqued the interest of the innovator ophthalmologist. "It hasn't moved to the early adopter, much less the middle adopter cataract surgeon," says Dr. Lindstrom.

"This is a procedure in evolution," adds Dr. Lane. "Ultimately, we will have the technology and the instrumentation necessary for micro phaco to have widespread applicability among all surgeons." It's just a matter of time.