As every retina specialist knows, many retina patients have glaucoma in addition to their retinal problems. Furthermore, addressing retinal problems can impact intraocular pressure, potentially putting such patients at risk.

Michael A. Klufas, MD, part of the Retina Service of Wills Eye Hospital and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia agrees that the conditions frequently overlap. “As retina specialists, some of the conditions we treat are associated with glaucoma and/or elevated intraocular pressure,” he says. “Those include retinal vein occlusions, retinal detachments and diabetic retinopathy, which can be associated with neovascular glaucoma. In addition, the periodic injections we give many of our patients may cause intraocular pressure fluctuations. IOP can sometimes trend higher in patients who’ve had multiple injections, so I have to be alert for that possibility to make sure the patient doesn’t lose vision from glaucoma. Furthermore, some of the surgeries we perform, such as repairing a chronic retinal detachment, can cause IOP to increase.”

Here, retina specialists discuss the issues that may arise in this situation and share their tips for how best to proceed.

Checking for Glaucoma

|

| Surgeons say that when a glaucoma patient comes in with pressure already elevated, the first thing they do is recheck the pressure to make sure the measurement was accurate. Some doctors prefer to use a Tonopen for this purpose; others favor the iCare tonometer. Photo: Adam Pflugrath, MD. |

Given that retinal procedures can have a serious impact on vision in a glaucoma patient—and not every patient with glaucoma has been diagnosed—many retina specialists say they routinely check their patients for evidence of the disease.

“Every time a patient comes in we look for signs of glaucoma,” says David S. Boyer, MD, a partner at Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group in Los Angeles and an adjunct clinical professor at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California. “We encounter glaucoma patients or suspects nearly every day. We may note increased cupping, an abnormal nerve fiber layer or very high intraocular pressure. Any of these will point me in the direction of having someone else involved who can follow the patient on an ongoing basis and do a more thorough glaucoma exam to determine whether the patient requires treatment.”

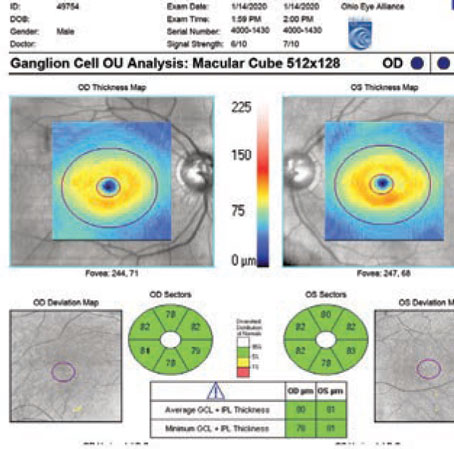

Noting that giving repeated injections may cause a pressure problem in some patients, Dr. Boyer says he always gets an OCT of the nerve fiber layer before he starts treatment. “No major study has verified this association, but getting an OCT of the nerve fiber layer at the outset gives me a good baseline for comparison later in case a problem arises.”

Adam Pflugrath, MD, a retinal surgeon at Jervey Eye Group in Greenville, South Carolina, believes that checking retina patients for the presence of glaucoma is incredibly important. “As retina doctors, we see patients more often than most—especially injection patients,” he points out. “As a result, we have a lot more data about both intraocular pressure and optic nerve head assessment.

“Every time I get an OCT of the macula I look at the infrared image of the nerve for any changes, just to see what’s going on,” he says. “I’ll pull up the last image and look to see if there are any changes. We can also use other options such as an RNFL scan, or some of the new metrics, like the Bruch’s membrane opening minimum-rim-width or area assessment, to track any changes.”

Dr. Pflugrath notes that he generally doesn’t rely on the OCT software-generated analysis, regarding whether signs of progression exist. “The software is good, but often you have to redraw the lines for the RNFL to get a more accurate measurement,” he points out. “Sometimes the machine misses the layer of the retina you want to evaluate. A brief look at the infrared image is a good quick assessment. In fact, you see more optic nerve head cupping when you look at the infrared image than you would looking at the slit lamp. Furthermore, taking that picture gives you another data point to assess later.

“Automated perimetry isn’t reliable in this population,” he adds. “Patients who’ve had prior panretinal photocoagulation laser for diabetes or vein occlusion, or who can’t maintain fixation because of macular edema or macular degeneration, aren’t going to perform as well on that test. We have the technology to get more objective measurements, so we might as well use it.”

If you find evidence suggestive of glaucoma, how should you proceed? Dr. Klufas says his decision about whether to recommend a glaucoma screening depends on a number of factors. “I look at the cup-to-disc ratio, whether the patient has a family history of glaucoma, and the IOP,” he explains. “If they have no risk factors and the cup-to-disc ratio is normal, I’m not sure they need a glaucoma screening. If they have a family history, but no other factors, I’d recommend getting the screening.

“Usually, if I suggest getting screened for glaucoma, the patient asks how soon to see someone about that,” he adds. “If their vision is fine, I’ll suggests doing it any time in the next six months, but I tell them not to wait for a year or two and risk permanent vision loss.”

Noting and treating particulate glaucoma Adam Pflugrath, MD, a retinal surgeon at Jervey Eye Group in Greenville, South Carolina, points out that particles left in the eye may lead to inflammation, which in turn can cause increased aqueous viscosity that can lead to elevated pressure. Particles left in the eye can also clog the trabecular meshwork directly, leading to the same outcome. “Retained lens particles following cataract surgery or lensectomy can cause this, as can silicone droplets and particles of perfluorocarbon liquid that weren’t removed,” he says. “This isn’t something most doctors think about when faced with elevated IOP, but retained particles are easily visible. Silicone oil floats to the top of the eye, while perfluorocarbon liquid and lens particles fall to the bottom of the anterior chamber, so you can see them at the slit lamp. “If the patient’s pressure is high as a result, you need to increase the steroids,” he notes. “If I see one of these cases in the office, I give the patient a periocular steroid to help lower the inflammation. Large lens particles, in particular, can be highly inflammatory. The steroid will help to soften up the particles and break some of them down, and it will help to keep the IOP from spiking due to the particles or the inflammation. “Of course,” he adds, “if you’re dealing with very large retained lens particles, you’ll also need to do a vitrectomy to remove them from the posterior and anterior segments.” —CK |

Elevated Pressure, Pre-injection

Most glaucoma patients need to have a low pressure to minimize the likelihood of progression. Occasionally, a glaucoma patient or suspect will show up for a retinal injection with their IOP already elevated.

Dr. Klufas says he may proceed with the injection despite an elevated IOP. “It depends on the pressure,” he notes. “If it’s 30 mmHg or less, I’ll typically just do the injection. Most of the intravitreal injections we do are 0.05 cc of volume, which the eye typically tolerates very well. Once I’ve done the injection I’ll recheck the pressure and confirm that the patient’s vision isn’t declining or blacked out, which would indicate very high pressure.”

Doctors note other points:

• Double-check the IOP yourself. Drs. Pflugrath and Klufas both double-check the IOP if it’s been measured as being elevated. “Often it was just spuriously high,” Dr. Klufas notes. “If I’m not sure the measurement was accurate, I tell the patient to breathe normally while I recheck it.”

• Consider the reason for the elevated IOP. “I’d probably proceed with an intravitreal injection, as long as the reason for the elevated eye pressure was just open-angle glaucoma, as opposed to residual lens material, bleeding secondary to trauma, or certain types of inflammation,” says Dr. Pflugrath.

• Consider making a paracentesis to avoid a pressure spike. “Doing a paracentesis immediately after the injection should help reduce the risk of pressure elevation,” says Dr. Pflugrath. “However, I don’t do this for every patient; I assess the optic nerve and IOP and decide if their optic nerve can handle the transient rise in pressure. Then I proceed with the injection using a 30-ga. needle.”

Dr. Klufas says he would generally only create a paracentesis in the presence of high pressure if the injection was urgent. “I’d consider a paracentesis if the patient, for example, has only one eye and if we don’t treat the neovascular macular degeneration the eye could get a bleed and vision loss.”

Dr. Klufas points out that some doctors inject a larger volume of drug based on the theory that more medication may allow increased duration of action. “I don’t believe this has ever been demonstrated in randomized, controlled studies,” he says. “However, if you do inject a larger volume, performing the anterior chamber paracentesis might make sense. It’s an easy step to add on, and it’s less painful than the intravitreal injection. In any case, If I do perform an anterior chamber paracentesis, I explain to the patient that the pressure problem needs to be addressed long term, which the paracentesis won’t do.”

Dr. Boyer says he rarely creates a paracentesis. “I know that some doctors do anterior chamber taps fairly often, but I haven’t found the need for it,” he explains. “If I think the patient is going to have a pressure elevation of any magnitude, I may add some drops beforehand, or do a little bit of ocular massage. For the most part, 0.05 ml of fluid isn’t going to cause a significant pressure increase.”

• Consider injecting a different agent. Dr. Pflugrath notes that another way to minimize the risk associated with post-injection IOP spikes is to use a longer-lasting anti-VEGF agent that requires fewer injections. “In retina patients with glaucoma or RNFL thinning, I prefer to use a more durable agent, if possible, whether that’s an intravitreal steroid or some of the newer anti-VEGF agents that can last more than four to six weeks,” he explains.

• Start a glaucoma drop, or send the patient back to the referring doctor. “Once I recheck the pressure, I’d review the medications the patient is on,” says Dr. Pflugrath. “If the pressure is in the high 20s or 30s, I’d probably add a drop, if that’s feasible, and let the referring doctor know.

“Depending on how high the pressure is, I might send the patient back to the other doctor to get it under control,” says Dr. Boyer. “If I see significant alterations at the level of optic nerve and the nerve fiber layer is compromised, then I may conclude that they need additional medication. If that’s the case, I’ll either call the other doctor or start the medication and ask the patient to see their doctor within the week, so they can get that taken care of.”

Dr. Klufas adds one point worth considering when performing an injection, regardless of whether or not the pressure is elevated. “Conserving conjunctiva is something to consider when treating a glaucoma patient,” he says. “I try to use conjunctiva away from the limbus, in case a glaucoma surgeon needs to do a procedure later.”

|

| Surgeons say they’d often proceed with an injection despite elevated IOP—if the pressure wasn’t too elevated, and the reason was open-angle glaucoma, rather than other causes such as trauma or inflammation. Some surgeons make a paracentesis after the injection if transient high pressure is especially risky for the eye, though it’s more common to start a glaucoma drop and/or send the patient back to the referring doctor to get the pressure under control. In any case, careful post-injection monitoring is always called for. Photo: Steve Charles, MD. |

Elevated Pressure, Pre-surgery

Doctors note that the considerations are somewhat different if the patient has come in for an invasive procedure and the pressure is already elevated. “In terms of proceeding with retinal surgery when the patient’s IOP is elevated, that would depend on how elevated the pressure was, and the cause,” says Dr. Pflugrath. “If this pressure is significantly elevated, I might postpone surgery to get the IOP under better control. If the pressure was minimally elevated, by only a few points and not requiring additional medication, then I might proceed with the surgery. On the other hand, if it was an elective procedure and the pressure was significantly elevated over baseline, I’d discuss additional medications or have them touch base with their glaucoma provider to see what could be done to lower the pressure more effectively before doing the procedure.

“In cases in which lens particles or a hemorrhage are causing the elevated IOP, I’d proceed with the surgery,” he adds. “If there was a retinal detachment, I’d go ahead with the surgery as well. However, you don’t usually see elevated pressure in that situation.”

If the patient was in the office for a procedure such as a retinal laser rather than an injection, Dr. Klufas says whether he’d postpone the procedure would depend on a number of factors. “I wouldn’t postpone a laser procedure intended to treat a retinal hole,” he notes. “That shouldn’t affect the pressure. But if it’s an invasive incisional, surgical procedure, my decision about proceeding would depend on how healthy the optic nerve looks. Someone with advanced glaucoma can lose all of their vision if the pressure reaches 40 mmHg, or whatever would be considered high for them, and the pressure can go up and down intraoperatively during retinal surgery.

“For that reason,” he continues, “if it’s elective surgery, I might say ‘Your vision is still pretty good, so let’s leave your eye alone.’ On the other hand, if it’s a retinal detachment that needs to be fixed or the patient might lose vision, postponing wouldn’t be an option. In that situation, I might take steps to make sure the pressure is normal before, during and after the surgery.

“Overall,” he adds, “the decision is pretty much patient-dependent, based largely on how healthy the optic nerve is.”

Managing the Steroid Dilemma

Because steroids can trigger an elevation in IOP in some individuals, a retina specialist may face a dilemma when steroids are the obvious—or necessary—treatment for a retinal concern. Surgeons say these strategies help ensure a positive outcome:

• See if the patient is a steroid responder. “If the patient has glaucoma, or we suspect he has glaucoma, there’s a good chance we’re not going to use steroids,” says Dr. Boyer. “If we do use them, we’re going to first try to see if the patient is a steroid responder, beyond just having glaucoma. I think the issue is steroid response even more than glaucoma, because some patients who don’t have glaucoma will go on to develop high pressure. You can’t really use steroids for those patients, unless the pressure elevation is mild and you can easily treat them with drops. Of course, if we do know the patient has glaucoma, I’d definitely be cautious.

“If I feel that steroids are necessary, I’d give the patient a trial of topical drops and monitor the patient for pressure elevation before giving any intravitreal injections,” he continues. “The drops may not even be the same steroid drug, but there may be enough of a correlation to get a sense of whether an injection is likely to elicit a pressure increase. Then, if the drops cause a pressure increase, you can stop the drops. If the drops don’t raise the pressure, I’ll probably do the injection with a steroid that has a short half-life and watch the patient very carefully.”

• Check the patient frequently postop. “Whenever I give an intravitreal steroid I have the patient come back five or six weeks later to make sure they’re not a steroid responder,” Dr. Boyer says. “In my experience, that’s usually when the peak pressure occurs.

“Unfortunately, even though you may not see a steroid response the first, second or third time you give the injection, it can happen on the sixth time,” he continues. “So we try to bring the patients back every time. If the pressure does rise, usually we can treat them with a glaucoma medication and the steroid response will subside after two or three months. Of course, if the patient initially comes in with severe glaucoma we’ll be much more concerned, because if the pressure goes up, we don’t have as many options left to treat the patient. We’d be less likely to use a steroid in that situation.”

Dr. Klufas points out that the timing of pressure elevation can vary with different medications. “Some may cause a pressure elevation two weeks later; some may cause it four to six weeks later,” he notes. “As a result, there’s no foolproof schedule for monitoring the patient. However, if the patient already has a tube or bleb, the pressure should ideally remain OK—especially if the patient has a tube.”

• Consider placing the steroid in the suprachoroidal space. Dr. Boyer notes that placing the steroid in the suprachoroidal space could conceivably lower the risk of a pressure increase. “Our practice participated in the original studies of Xipere, a triamcinolone acetonide injectable suspension designed to go into the suprachoroidal space,” he explains. “It didn’t seem to cause the pressure rises I would have expected. However, I don’t have enough patient experience to be able to say unequivocally that this is true.”

• Consider switching to anti-VEGF drugs. “If the condition we’re treating is cystoid macular edema or inflammatory disease and we can’t use steroids because of the inflammation, we tend to switch to using anti-VEGF drugs,” says Dr. Boyer. “In many cases, those drugs will get rid of the edema without causing the pressure to rise.”

• Treat prophylactically to prevent steroid-related IOP elevation. Dr. Pflugrath admits that using steroids when a patient is a known steroid responder is sometimes unavoidable. “That’s a challenging situation,” he says. “For example, you might have a steroid responder who has chronic edema that just won’t go away. I’ll often prophylactically put that patient on a topical glaucoma drop, if they’re not already on one, to minimize any potential post-steroid IOP spike and any fluctuations in IOP.”

Dr. Pflugrath notes that in this situation he wouldn’t prescribe a prostaglandin as a first-line agent. “I’m trying to avoid putting a financial burden on the patient,” he explains. “They could have to fork over hundreds of dollars for a drop, if their insurance won’t cover it, so I try to start with a generic dual agent—whatever will be least expensive for the patient. For example, dorzolamide/timolol is a readily available generic drop. The dual nature of the drop is also helpful because many of these patients have never used a glaucoma drop. If I ask them to use something more than twice a day, they may not be compliant.”

Dr. Klufas says he doesn’t generally prescribe a glaucoma drop when giving steroids. “Steroids don’t always cause glaucoma, so it may not be necessary to do that routinely,” he says. “However, if I give a periocular steroid, I tell the patient that I’ll need to check the pressure regularly. Some of those patients may end up needing a glaucoma drop, and one in a few hundred may need glaucoma surgery, so I warn patients about that possibility before proceeding with a steroid injection.”

• Consider using the Susvimo port delivery system. Dr. Pflugrath believes the new Susvimo port delivery system implant for diabetics and macular degeneration patients (Genentech) may help to minimize IOP spikes. “A lot of patients with diabetes or macular degeneration also have glaucoma,” he notes. “When you place an implant in these patients, you don’t see the same post-injection IOP spikes because the patients rarely require further injections.

“The problem,” he adds, “is that if the patient has had glaucoma surgery, or has advanced glaucoma that may require a shunt, you’re limited as to where you can place the implant and still have adequate conjunctival covering to minimize any potential infection risk.”

• Choose a less-potent steroid. “We have different choices in terms of which steroid we use,” notes Dr. Klufas. “There are some steroids like FML (fluoromethalone ophthalmic suspension) or Lotemax or Alrex, that are less potent than other options such as Durezol.”

• Consult with a glaucoma specialist before proceeding. Dr. Klufas says that if he plans to inject a steroid intraocularly or periocularly and he’s concerned about the patient, he’ll consult with a glaucoma specialist before proceeding. “In my experience, they’ll usually tell me it’s fine to proceed, as long as the patient is being monitored appropriately after the injection,” he says.

If a Tube or Bleb is Present

“Obviously if you’re giving injections, you have to stay away from any existing trabeculectomy bleb or tube shunt,” says Dr. Boyer. “You don’t want to precipitate any breakdown of a functioning drainage system or cause a leak, even with a small needle. So if a tube or bleb is located superiorly, where I normally give my injections, I’ll go inferotemporally for the injection. I always stay away from tubes and trabs.”

Dr. Pflugrath also says he’d avoid the quadrants that contain the bleb or tube. “Typically, I do most of my injections inferotemporally, to minimize scarring in the superior conjunctiva,” he explains. “That way, if the patient needs a future glaucoma surgery, it won’t interfere with it.”

Dr. Pflugrath points out that the presence of a tube or prior trabeculectomy in this situation is good, in that it lowers the risk of a postop pressure spike. “A post-injection IOP spike has been shown to decrease the retinal nerve fiber layer thickness,” he points out. “If the patient has a condition like diabetic macular edema, vein occlusion or chronic uveitis with macular edema, and needs a steroid injection, having a tube or a prior trabeculectomy makes me worry less about having steroid-induced glaucoma. Their aqueous is already bypassing the trabecular meshwork.

“If they haven’t had a tube or trabeculectomy or some other shunt procedure, I’m more likely to do an anterior chamber paracentesis with an intravitreal injection and use a different size needle—27-ga. or 30-ga. instead of 32-ga.—to minimize post-injection IOP spikes,” he continues. “That helps, because the larger-diameter needle allows a little more leakage until the sclerotomy closes. It’s a safety valve of sorts.”

Glaucoma and Vitrectomy

“Depending on the degree of damage seen at the nerve, you don’t want to have high pressures during a vitrectomy, and you don’t want to leave the patient with high pressure,” says Dr. Boyer. “I’ve seen people lose vision because of that. For example, a colleague came to me seeking a second opinion after a vitrectomy he underwent caused him to lose vision, secondary to increased IOP during his surgery.”

|

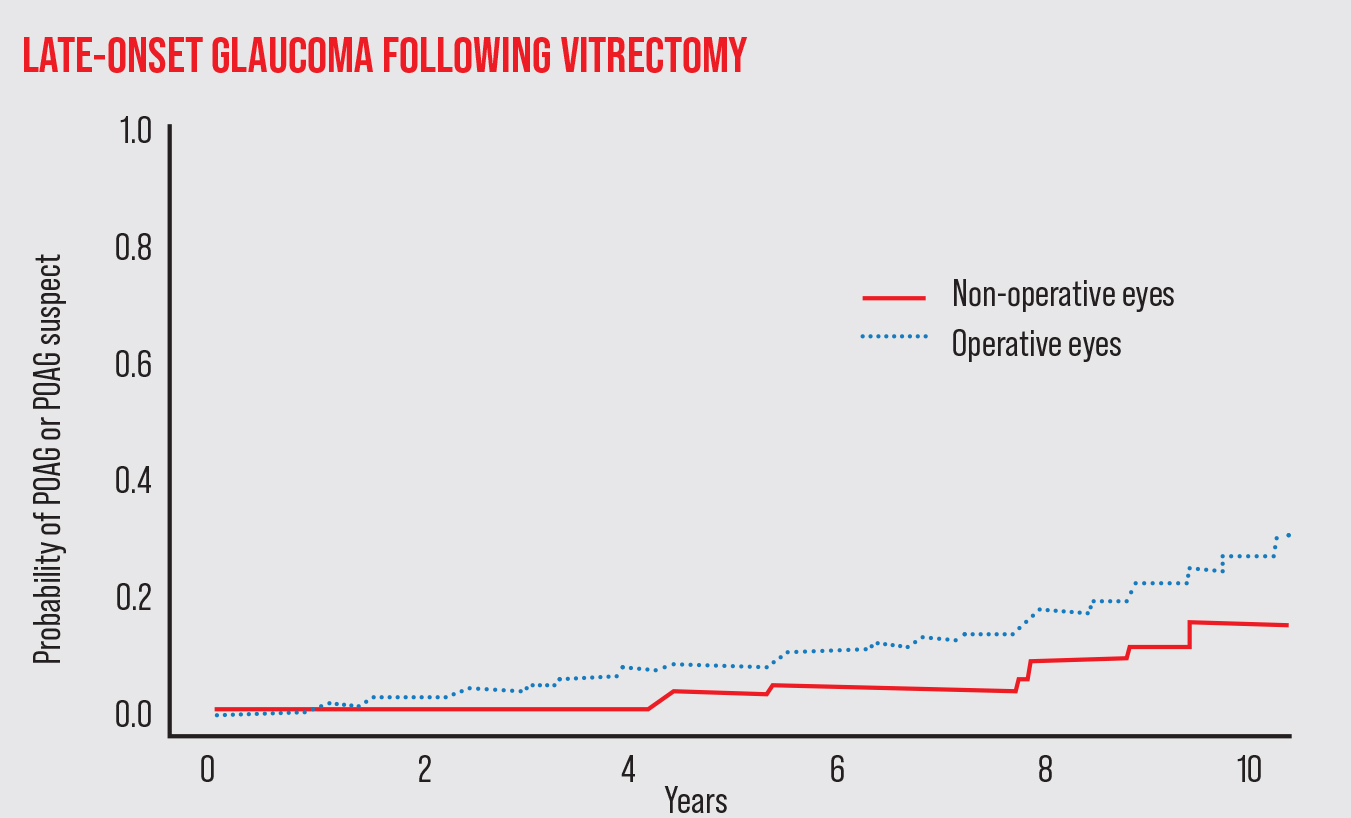

| In addition to issues of pressure elevation during and immediately after a vitrectomy, studies suggest that patients are at increased risk of developing open-angle glaucoma in the years following the procedure. For example, one study published in 2018 by Mansukhani et al followed 277 patients who had a vitrectomy in one eye.1 The risk of developing POAG in the operative eye after multiple years was significantly greater than in the non-operative eye, suggesting that long-term monitoring of these patients is justified. |

Dr. Pflugrath says that when performing a vitrectomy in a patient with glaucoma, he chooses the location for the ports based on both current and future considerations. “If the patient has had a filtering procedure, you obviously don’t want to put the port in through the bleb or near the tube,” he says. “I typically do a lot more of my trocar placements closer to the equator, as opposed to the traditional 10:00 and 2:00 placement. In addition, if the patient has more severe glaucoma and I’m sitting superiorly, I’ll put things closer to the equator to avoid causing any conjunctival damage or scarring, in case the patient needs to have glaucoma surgery in the future.

“One other consideration in this situation is that I’ll lower my infusion pressure during the vitrectomy,” he adds. “And, I’ll keep an eye on the optic nerve head and the blood vessels. I want to avoid any arterial pulsations. Pulsations imply that the pressure’s too high in the eye, potentially decreasing the blood flow. So, if I see any, I’ll lower the infusion pressure until they go away, to optimize blood flow and minimize nerve head damage.”

“The use of steroids following the vitrectomy is also a concern,” Dr. Klufas adds. “I usually give a steroid injection at the end of a case, but in a case like this I might forgo that, or just give a smaller amount, putting them only on topical steroids drops instead. Of course, the drops could elevate the pressure too, but they can be stopped.”

Glaucoma and a Gas Bubble

Dr. Pflugrath says that when a glaucoma patient requires surgery that calls for a gas bubble to hold the repaired tissue in place, it’s important to make sure the IOP isn’t too elevated after the bubble is created. “If it’s elevated, you need to adjust the IOP in the OR before the patient leaves,” he says. “Ideally, you’re using an isoexpansile gas concentration that will minimize any potential IOP elevation that first day, while the eye is patched and the patient’s not getting any eye drops. You want a good gas fill without an overfill.”

He notes that using a gas bubble offers plenty of opportunity to unintentionally generate excess IOP. “Make sure you’re using the correct concentration of gas,” he says. “You want to get as close to an isoexpansile mixture as you can,” he says. “Gas expansion and overfill-related pressure problems are potentially blinding, irreversible complications that are avoidable if you get the right concentration.

“A common mistake, for example, is to record the number of cubic centimeters of gas needed in your protocol notes, but fail to recalculate if a different, smaller syringe ends up being used for the procedure,” he notes. “Another mistake is believing that severe proliferative retinopathy should be addressed with a higher concentration of gas; there’s no evidence to support that idea. Finally, make sure the IOP isn’t elevated at the time of closing.”

He adds one other potentially devastating mistake. “Sometimes a doctor will prescribe postop pain medication, as needed, for a patient with a gas bubble,” he says. “If the patient is in pain, it could indicate that the gas concentration is incorrect, rather than being simple postoperative surgical pain. If oral medications mask that pain, the patient may return to your office with serious vision loss and optic nerve ischemia.”

“Generally, I try to avoid expansile gases in a glaucoma eye,” says Dr. Klufas. “Sometimes I dilute the gas a little bit more than I would otherwise, to avoid any chance of expansile gas. Of course, even if the concentration is correct, you can still have pressure issues postoperatively. One option is to have the anesthesiologist give Diamox, either orally or intravenously, at the end of the case to keep the pressure on the lower side. Too low a pressure isn’t good either, of course, but sometimes that medication can lower it just enough to avoid a problem.”

Dr. Boyer notes another issue. “If the patient has had a filtering operation, you don’t want the gas bubble to go into the anterior chamber and block it,” he says.

Silicone oil in Avastin Syringes Michael A. Klufas, MD, part of the Retina Service of Wills Eye Hospital and an assistant professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, notes a problem that has cropped up when injecting off label intravitreal Avastin to address macular degeneration or other vitreoretinal conditions. “Sometimes the syringes are contaminated with silicone oil, just because of the way the compounded Avastin is prepared,” he explains. “The oil lubricates the plunger, but that oil can be injected into the eye. Sometimes a big oil bubble gets injected and patients may experience a visually significant floater. “Patients who’ve had three shots of Avastin from syringes contaminated with silicone oil will almost always have some small oil droplets in the vitreous cavity, which could potentially lead to glaucoma in some patients,” he notes. “Doctors don’t look for it all the time, but it’s there. “You can still buy Avastin in insulin-type needles,” he continues. “It’s very convenient because it’s an all-in-one thing; you just pull the cap off and inject the medication. From a sterility standpoint it’s good, because you don’t have to put the needle on yourself, and it’s cheaper, too, because you can pull more doses out of the compounded Avastin vial. Unfortunately, silicone oil contamination has been reported with all kinds of intravitreal medications, and compounded Avastin has the highest rate of silicone oil contamination when repackaged into certain types of syringes that aren’t silicone-free.” Dr. Klufas points out that silicone-free preparations are now available. “Most practices have transitioned,” he says. “They’re more expensive, but to me the silicone oil contamination is a problem worth addressing. Unfortunately, with the pandemic it’s been harder to get the silicone-oil-free syringes, due to supply chain problems. “At this point, we still use a silicone-free preparation, but now we have to place a needle on the syringe ourselves,” he concludes. “That’s a sterility concern for some doctors, and the needle may not be as secure on the syringe, as compared to a silicone-oil-free syringe that has the needle built in. This isn’t ideal.” —CK |

Glaucoma and Silicone Oil

Dr. Klufas doesn’t favor the use of silicone oil as a first option in a patient with severe glaucomatous vision loss. “There’s definitely a higher morbidity with silicone oil in this situation,” he says. “Doctors have reported optic neuropathies with this treatment, so it’s not my preferred option in a patient who already has some vision loss from glaucoma. The silicone oil doesn’t usually cause glaucoma directly, but there are reports of oil causing damage to the optic nerve, as well as secondary glaucoma. And, even when you remove the oil in the future, there are always little droplets left in the eye that can clog the trabecular meshwork and lead to glaucoma. Nevertheless, sometimes there’s no other option and silicone oil is required.

“If I do have the option, I’d choose the gas,” he says. “It will cause temporary changes in the intraocular pressure, but it reabsorbs over time.”

Dr. Pflugrath points out that it’s crucial to avoid over-injecting silicone oil. “Always use a tactile pressure check to make sure the eye isn’t overinflated,” he says. “Oil can’t compress, and glaucoma medications won’t be able to offset a pressure increase caused by excess silicone oil.”

“If there’s a tube in the posterior segment, silicone oil would be contraindicated because you’re going to block the tube,” notes Dr. Boyer. “Then the pressure will go up. If the tube is in the anterior chamber, you could be fine as long as oil bubbles don’t go into the anterior chamber. And if a patient without a tube developed a pressure increase with silicone oil present, the surgeon would still have the anterior chamber available to put a tube in. So, I’d avoid using oil if a tube was in the posterior chamber. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be too concerned about it.”

Dr. Pflugrath points out another potential problem that can affect retina patients who have glaucoma: Conditions that make the aqueous more viscous—including flare caused by silicone oil—can cause IOP to rise simply because more viscous fluid doesn’t drain as well. “Inflammation will increase viscosity quite a bit,” he says. “VEGF will also. Anything that causes high protein content will lead to more viscous fluid that raises the pressure. Conversely, treating the cause of that with an anti-VEGF injection or a steroid will help lower the IOP.

“You can also see this in patients with silicone oil who have a lot of flare,” he continues. “Flare is a marker of proteinaceous changes, making the anterior chamber fluid more viscous. So, if a patient has silicone oil in place and you can’t take it out, and they have a lot of flare in the anterior chamber and the IOP’s going up, a periocular steroid injection can help. It can get rid of the flare and inflammatory particles and lower the viscosity of the aqueous, which will, in turn, lower the IOP.”

Working With a Glaucoma Colleague

Dr. Klufas says that working with a glaucoma specialist in many of these cases makes sense. “It’s definitely valuable to be able to comanage a patient so that we can combine our expertise to address any vision-threatening problems,” he says. “For example, when dealing with the nuances of recent glaucoma medications, it’s often helpful to have the patient be seen by a glaucoma doctor who prescribes these medications frequently and is well-acquainted with their side effects.

“For example, if the patient has asthma or a heart problem, timolol isn’t ideal,” he notes. “In retina we’re often worried about inflammation, and prostaglandins like Xalatan or Latanoprost may cause inflammation. Some people get follicular conjunctivitis from brimonidine. And, there are new drops like Vyzulta and Rhopressa. I’m up to date on all of the latest anti-VEGF compounds; that’s my area of expertise. But doctors who work with these new glaucoma drops every day have much more experience with them than I do.

“The other issue is practice workflow,” he adds. “I can prescribe a drop, but my practice is treating macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. Our workflow is set up to take care of injection and retina patients. In contrast, a general eye care doctor or glaucoma specialist is set up to manage glaucoma. There’s safety in being managed by a doctor who treats glaucoma all day, every day.”

Dr. Boyer agrees. “The reality is, our practice isn’t set up to fully evaluate or manage glaucoma,” he says. “For example, we don’t have the ability to measure corneal thickness. I think it’s better to put the patient back in the hands of someone who can follow them and do the appropriate testing on an ongoing basis.”

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Klufas is a consultant for Genentech, Allergan, RegenexBio and Alimera, and a speaker for Genentech and Regeneron. Drs. Boyer and Pflugrath report no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Mansukhani SA, Barkmeier AJ, Bakri SJ, et al. The risk of primary open angle glaucoma following vitreoretinal surgery—a population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;193:143–155.