As one of the rarer complications in cataract surgery, a posterior capsular break can rattle even the most experienced surgeon. How they react to this event, when vitreous is prolapsing, sets the course for completing the surgery and successfully implanting an IOL. However, there is no standard when it comes to addressing this complication, and anterior segment surgeons find themselves divided between a limbal-based or pars plana vitrectomy.

No matter which side of the debate you fall on, there seems to be increasing awareness of the advantages of knowing both approaches. We spoke with several experts who shared their pearls and experiences to better prepare you for your next unplanned vitrectomy.

Risk Factors and Reactions

A posterior capsular tear can occur at almost any step of surgery, but is most common during the last stages of nuclear emulsification.1 At this stage, most of the nuclear material is gone and the bag is no longer open, making it more prone to collapse. Looking for and recognizing abnormalities preoperatively with a careful history and exam will help surgeons prepare for this complication.

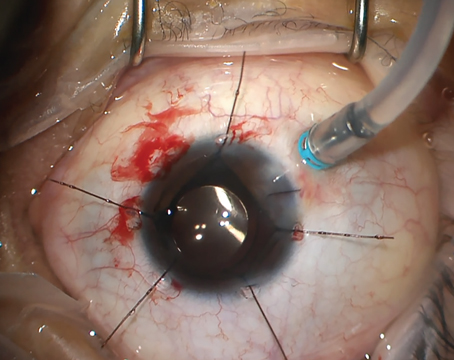

|

| The benefits of a pars plana vitrectomy with sideport infusion include less endothelial damage than trans-limbal vitrectomy, better anterior chamber stability, and the fact that residual lens cortex can be removed, proponents say. Photo: Steve Charles, MD. |

Neil J. Friedman, MD, adjunct clinical professor, department of ophthalmology at Stanford University School of Medicine and partner at Mid-Peninsula Ophthalmology Medical Group in Menlo Park, California, says recognizing risk factors beforehand allows surgeons to modify surgical techniques to reduce the likelihood of this complication. “Risk factors for capsular breaks include conditions that may weaken the capsule or zonules (i.e., pseudoexfoliation syndrome, ocular trauma, ectopia lentis, posterior polar cataract, previous vitrectomy or intravitreal injections) as well as those that limit visualization of the capsule (i.e., poor pupillary dilation, intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, mature cataract, corneal opacity or edema),” he says.

“Surgeons should always be attentive to the warning signs of capsular rupture while performing hydrodissection, phacoemulsification, cortical cleanup and IOL insertion, and be prepared to respond accordingly,” Dr. Friedman continues.

Nearly every surgeon remembers the first time this happened to them, likely during their residency. “I first broke the capsule during senior year of residency after approximately 20 uncomplicated cataract cases,” Dr. Friedman says. “I don’t recall the specifics, but I do remember that after the lens nucleus had been removed, I was staring at a large posterior capsular rent with vitreous prolapsing to the scleral tunnel incision. The attending surgeon guided me through the correct steps to complete the case, and the patient subsequently did well with a sulcus IOL.”

That calm, measured response makes a difference. “When you encounter a rupture, you’re likely to have a moment of disbelief and denial somewhat. Your heart just sinks and there are two common reactions: one is to just keep going as if nothing happened; and the other is to come out of the eye—and those are both wrong,” explains Sumitra Khandelwal, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine, Cullen Eye Institute, and medical director for the Lions Eye Bank of Texas.

She says surgeons have to get past that moment of disbelief and take the necessary steps to control the situation. “What you don’t want to do is ignore a complication and keep going and then accidentally do something like phacoemulsifying vitreous, which is very, very bad for the patient,” she advises.

Dr. Friedman says the most common mistake is to remove all instruments from the eye without first pressurizing the anterior chamber with OVD. “If the surgeon suddenly removes the irrigating instrument (i.e., phaco probe or I/A handpiece), the anterior chamber collapses and the vitreous moves forward,” he says. “This results in extension of the capsular tear, vitreous prolapse, possible vitreous loss through the wound and possible posterior migration of remaining nuclear material. This sequence of events makes the remainder of surgery more difficult and increases the risk of postoperative complications.”

Dr. Khandelwal agrees, saying, “The first steps you need to take are to stabilize the eye with dispersive viscoelastic to tamponade the vitreous, turn off your irrigation and come out of the eye, making sure it’s pressurized, and then examine the situation.”

“The patient can have a very successful outcome with a posterior capsule tear,” says Thomas A. Oetting, MS, MD, clinical professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at University of Iowa Health Care. “Surgeons should slow down and be careful not to put traction on the vitreous, which has likely prolapsed more anterior into the field of surgery. The amount of remaining nucleus will play a big role in the flow of the rest of the surgery. When only a small amount of nuclear material remains, the anterior segment surgeon can usually complete the case.”

Determining Your Approach

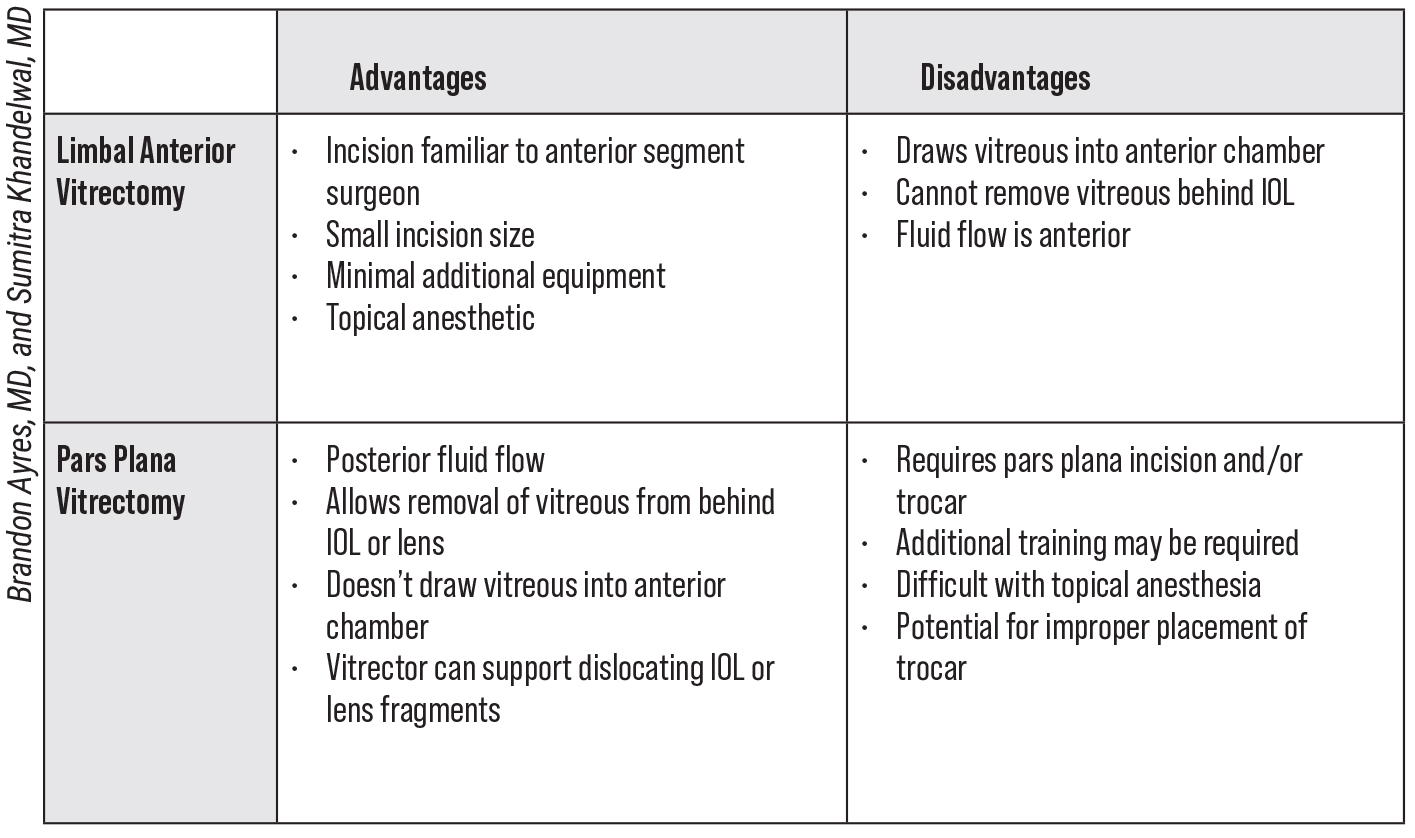

|

| The spider-like appearance on the posterior capsule could signify a break and require a vitrectomy. Photo: Lisa Brothers Arbisser, MD. |

That leads us to the controversy of the limbal-based approach versus pars plana vitrectomy. Each comes with inherent risks, says Dr. Friedman. “The controversy is regarding safety. An anterior vitrectomy increases the risk of retinal tear, which can lead to retinal detachment. Therefore, it’s important to minimize traction on the vitreous base (i.e., avoid pulling vitreous by using slow movements, high cutting rate and low aspiration/vacuum settings). With the pars plana approach, it’s also necessary to avoid vitreous incarceration in the sclerotomy site,” he says.

Comfort level is also important. After all, as Dr. Khandelwal says, “the time to try new things is not in the middle of a complication.” For this reason, most anterior segment surgeons opt for the limbal-based vitrectomy. “When anterior segment surgeons learn to do intraocular surgery, they’re very focused on the anterior chamber and the wounds are at the cornea, which makes complete sense because that’s where you do your cataract moves,” she says. “There’s no guideline out there saying that’s the incorrect approach. And quite frankly, in most people’s hands, that’s the safest approach because they’re very comfortable with it.”

Dr. Khandelwal warns, though, that the vitreous is like a little Pandora’s box. “Vitreous goes from the back of the eye to the front of the eye if your instruments are in the front, so you’re almost constantly pulling vitreous out if you’re not careful during the limbal-based approach,” she says.

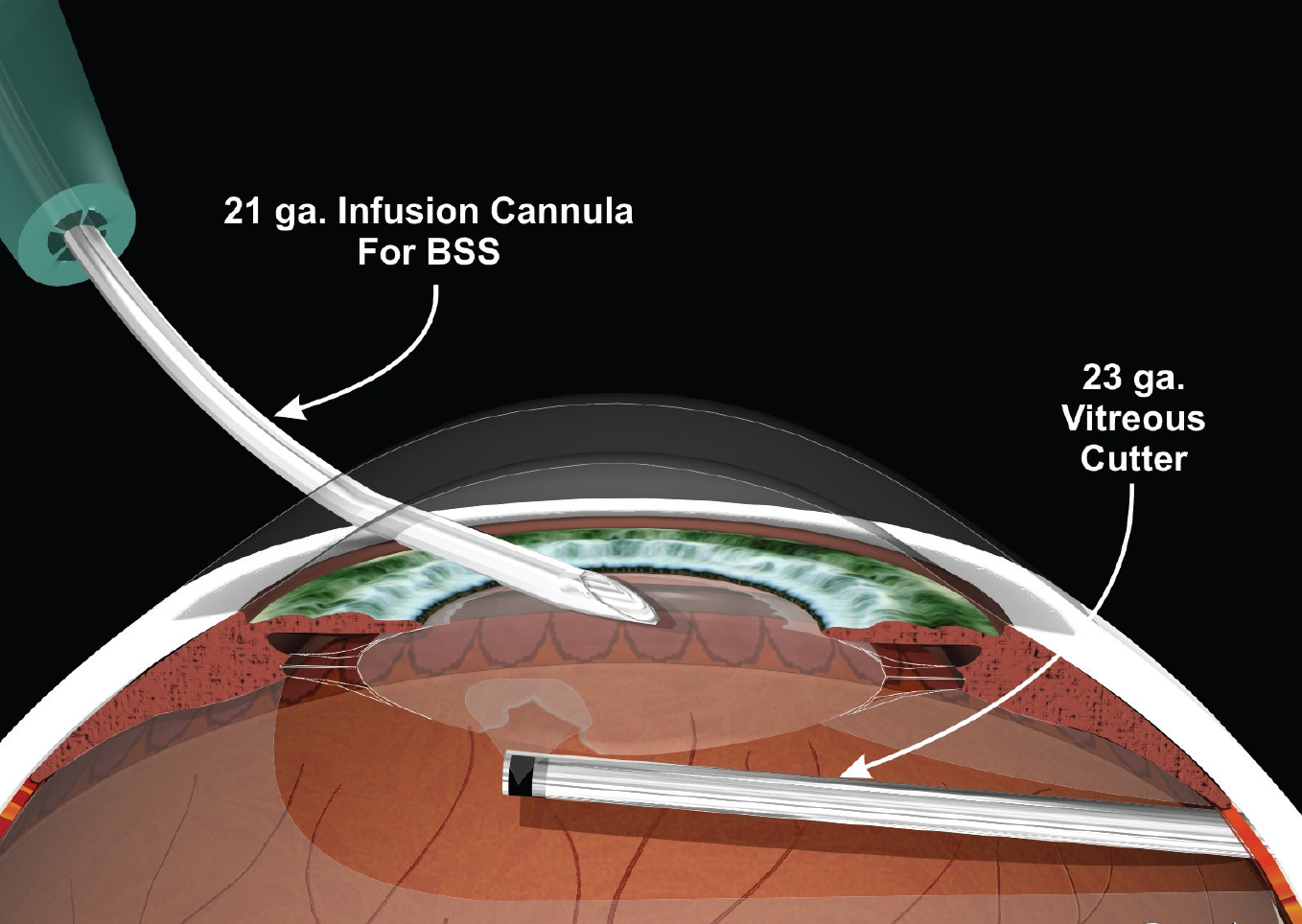

Regardless of location, the vitrectomy must be bimanual, not coaxial, Dr. Friedman says. “The infusion line is separated from and placed above the cutting instrument to minimize vitreous hydration and further prolapse,” he explains. “The infusion (attached to a cannula, bimanual I/A handpiece, or anterior chamber maintainer) is placed through a corneal paracentesis and the cutting probe is placed either through a separate watertight corneal sideport incision or through the pars plana 3.5 mm posterior to the limbus. Always keep the tip of the vitrector in view.

“The advantage of the pars plana approach is the position of the instrument relative to the vitreous (i.e., below to pull vitreous posteriorly, instead of from above, which risks pulling vitreous anteriorly),” he notes. “If there’s a large amount of vitreous prolapse, the pars plana approach usually provides a more complete, safer and quicker removal. In addition, a spatula or OVD cannula placed through the pars plana incision can be used to elevate nuclear fragments using the posterior assisted levitation (PAL) or VisCoat trap technique, respectively. For a small, isolated knuckle of herniated vitreous, I believe the anterior approach through the cornea is easier, faster and equally effective.”

It’s Dr. Khandelwal’s opinion that every anterior segment surgeon should be comfortable with both the limbal-based and pars plana approach to anterior vitrectomy. “The pars plana approach is just not taught that much, but the goal is for everyone to be comfortable with the anatomy and where to insert the trocar for a pars plana approach,” she says.

Dr. Oetting says there are specific instances that may exceed the anterior segment surgeon’s skill set. “Sometimes, the entire nucleus simply drops into the vitreous chamber,” he notes. “This complication often occurs at the time of hydrodissection, especially if the capsule was compromised from a pre-existing injury from past surgery, trauma or needle injury. The anterior segment surgeon shouldn’t chase the nucleus back. The surgeon should simply leave the nucleus posterior and continue with the anterior vitrectomy, cortical clean up and IOL placement. Retina surgeons will later perform a pars plana vitrectomy and lensectomy to remove the posterior segment lens material.”

|

Limbal-based Anterior Vitrectomy Tips

If limbal-based vitrectomy is in your comfort zone, Dr. Friedman offers the following tips:

- Close the existing cataract incision (hydration or suture) and use the appropriately sized MVR blade to create incisions that don’t leak;

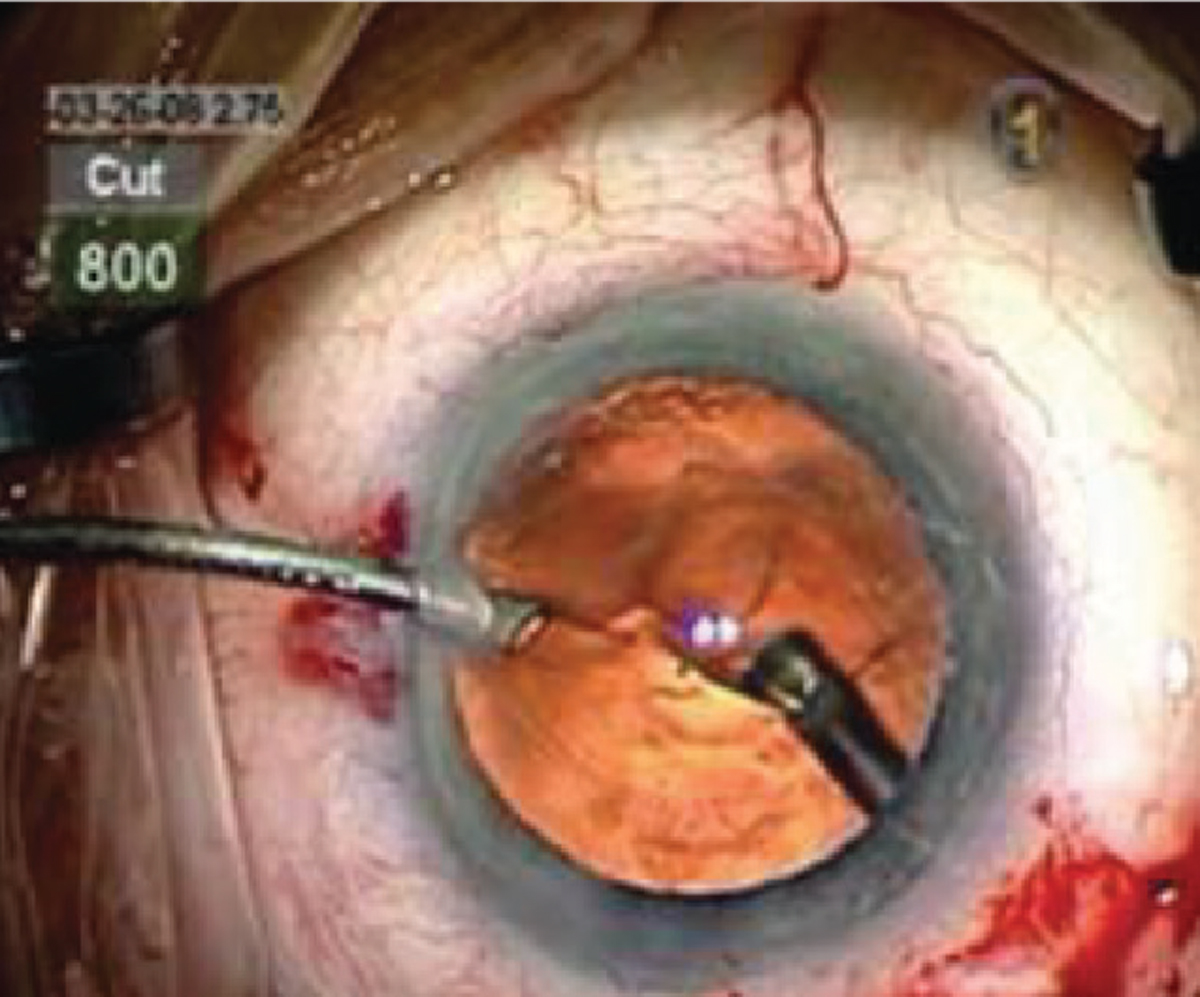

- Separate the infusion from the vitrector handpiece. The vitrector should initially be set to “cut/ I/A” with the highest cutting rate and a low aspiration rate to safely remove vitreous;

- After removing all vitreous above the posterior capsule plane, the vitrectomy setting can be changed to “I/A cut” to aspirate any cortical material in the capsule. If additional vitreous enters the area during cortical removal, then the setting can be switched back to “cut / I/A” to continue the vitrectomy. Alternatively, cortex can be manually aspirated with a cannula using a dry technique (i.e., OVD repeatedly injected to maintain space without irrigation);

- An intracameral steroid (i.e., triamcinolone acetonide [Triessence or Kenalog]) can be injected to better visualize the vitreous; and

- Avoid sweeping the wound with a spatula or using a Weck-Cel spear to check for the presence of vitreous loss from wounds, because these maneuvers cause excessive vitreous traction.

Perks of Pars Plana

Dr. Khandelwal says she prefers the pars plana approach because you’re entering your ports 3 mm posterior to the limbus. “You’re actually behind the lens and behind the area where the posterior capsule is. Instead of letting the vitreous come to the front of the eye, you’re stopping it and cutting it at a plane where it’ll stay back,” she says. “That’s why it’s a much more efficient approach.”

Good visualization is key. “You should never go back there if you’re not sure you can see your ports because you may inadvertently cut something,” says Dr. Khandelwal. “It’s much more dangerous to cut something near the retina than it is to cut something in the anterior segment. Retina surgeons can go really far posterior—they’ve got excellent microscope devices that can give them a really good view.

“Companies make certain trocars that are specific to anterior segment surgeons with just the specific things you need, so you don’t have to pull up the whole retina tray anymore,” Dr. Khandelwal adds. “You can also just use an MVR blade to insert it, but the key is to measure back to where you need to insert it to visualize your ports, and then to use techniques similar to the limbal approach. If you have the correct instruments, it’s always better to do a pars plana approach.”

There’s always an opportunity to reverse course. “If you start the pars plana vitrectomy and realize you don’t feel comfortable, you can switch back to a limbal-based approach,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “Nothing says you have to use the pars plana incision you made, but no matter which way you do the vitrectomy, you want to close your wounds.”

Placing the IOL and Postoperative Care

|

| After removing all vitreous above the posterior capsule plane, the vitrectomy setting can be changed to “I/A/cut” to aspirate any cortical materials in the capsule. Photo: Lisa Brothers Arbisser, MD. |

Dr. Oetting says the status of the remaining capsule drives placement of the IOL. “If the anterior capsule is also torn but the zonules are solid, surgeons can often place a sulcus-based three-piece IOL,” he says. “If the IOL doesn’t seem stable, it can be sutured to the iris immediately or later. If the anterior capsule is also torn and the zonules are weak, then the capsule will offer little support.”

“A single-piece posterior chamber IOL may be secure in the capsular bag if there’s a small capsule tear, particularly if it’s central and can be stabilized by creating a posterior capsulorhexis,” says Dr. Friedman. “The IOL optic can also be captured anteriorly or posteriorly through the anterior or posterior capsulorhexis, respectively. If a lens can’t safely be implanted in the bag but there is sufficient anterior capsular support, then a three-piece IOL can be placed in the sulcus, preferably with optic capture through an intact capsulorhexis. If there’s not enough capsular support, then, depending on surgeon preference, you can place a three-piece posterior chamber IOL in the sulcus with suture fixation (to the iris or scleral) or intrascleral haptic fixation (glued or Yamane technique), or you can implant a flexible, open-loop anterior chamber IOL.”

The final steps of the surgery have a major influence on patient recovery.

“Anytime you have to do an unplanned vitrectomy, you want to make sure to suture your wounds and pressurize the eye, making sure the pressure control is adequate, whether that be with drops or Diamox,” Dr. Khandelwal says. “You also want to make sure that you do a good, dilated exam looking at the peripheral retina. If, for some reason, you feel this patient’s high-risk or you’re concerned about fragments of a cataract in the back, it’s very important to refer early to a retina specialist so they can intervene.”

Dr. Friedman concurs. “In terms of managing remaining nuclear material, the surgeon should elevate any nuclear material from the capsule into the anterior chamber and consider inserting a Sheets glide to prevent posterior migration,” he says. “Low-flow phaco can be used to remove small pieces, whereas it may be necessary to enlarge the wound or create a scleral tunnel incision to manually extract large pieces. Don’t attempt to retrieve nuclear fragments that have dislocated into the vitreous cavity. These should be removed at a later date by a retina specialist. Always keep the anterior chamber well-formed with additional OVD as needed, and resume anterior vitrectomy whenever vitreous migrates anteriorly.

“Patients should also be made aware of the surgical complication and possible longer visual recovery,” he concludes.

Final Pearls

When confronted with this complication, experts offer the following pearls:

- recognize the potential for vitreous prolapse;

- prevent the anterior chamber from collapsing by injecting a dispersive OVD to stabilize the eye and tamponade the vitreous before removing the automated handpiece;

- stop irrigation;

- consider Triessence or dilute Kenalog to visualize the vitreous;

- if vitreous is present, use bimanual anterior vitrectomy with high cut settings;

- a limbal approach requires two paracenteses but may bring vitreous to the anterior chamber; keep the irrigator anterior to the iris plane while positioning the vitrector posteriorly to cut, prior to movement to the anterior chamber;

- pars plana requires a scleral incision 3 to 4 mm posterior to the limbus using a blade or a trocar;

- be sure your incision and settings match the gauge of your vitrector;

- extract any lens fragments remaining in the anterior segment, and remove all prolapsed vitreous;

- once vitreous has been cleared, use viscoelastic to keep the anterior chamber stabilized and proceed with the next steps for surgery;

- at the end of the case, check for remaining vitreous using dilute Kenalog or Miostat to bring the pupil down, or an air bubble may be warranted;

- implant an IOL in the most appropriate location and make sure it’s secure; and

- suture the wounds properly.

Ultimately, planning ahead will be the key to success, and knowing both techniques will ensure you’re prepared if vitreous loss occurs during cataract surgery.

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Friedman, Dr. Oetting and Dr. Khandelwal report no relevant financial disclosures.

1. Prasad S, Little B, Osher R. Anterior vitrectomy masterclass. September, 2011. Congress of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Vienna, Austria. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.escrs.org/vienna2011/programme/handouts/IC-48/IC48_Prasad_handout.pdf.