The Power of Cross-linking

“Cross-linking is a major advance,” notes Roy S. Rubinfeld, MD, MS, in private practice and a clinical associate professor at Georgetown University Medical Center. “It’s the first and only treatment demonstrated to effectively strengthen the cornea and stop the progression of keratoconus or ectasia. Furthermore, it’s been well-tested since it was originally introduced in the late 1990s by Michael Mrochen, PhD, and Theo Seiler, MD, PhD, in Dresden. It’s expected to markedly reduce the number of corneal transplants performed in the United States, which is very good news.

“At the same time, it’s important for surgeons to realize that the currently approved version of cross-linking [with removal of the epithelium] is not to be taken lightly,” he says. “It’s crucial to pay attention to patient selection and ocular surface assessment and treatment, both preoperatively and postoperatively. In my experience, healing after cross-linking is even slower and more critical than it is following PRK. Patients with ocular surface disease, as well as patients with very steep corneas, are at higher risk for delayed epithelial healing and potential complications, so surgeons should monitor their patients frequently until the epithelium regrows.”

|

| Corneal collagen cross-linking is the only treatment that’s been shown to strengthen the cornea and stop the progression of keratoconus or ectasia. |

Peter S. Hersh, MD, FACS, clinical professor and director of cornea and refractive surgery at the Institute of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, was medical monitor for the trial that led to Avedro’s FDA approval. “The first of the two FDA approvals to date was for collagen cross-linking for the treatment of progressive keratoconus,” he explains. “Although crosslinking may improve the corneal topography modestly in some cases, the primary goal of crosslinking is stabilization of the disease process, so you want to be sure that you’re dealing with progressive keratoconus. Also, for this indication, the patient should be age 14 or older.”

The second indication, which received FDA approval this July, is as a treatment for corneal ectasia after refractive surgery. “In our own studies we’ve found this procedure to be as effective in stabilizing ectasia as it is keratoconus,” notes Dr. Hersh. “However, ectasia patients tend to have less of a change in topography than keratoconus patients. This may be because the topographic irregularities in ectasia are less severe than in keratoconus, or because the topographic elevations tend to be more eccentric.”

Using the System

Dr. Hersh notes that the approved procedure is a standard epi-off protocol. “The Avedro system produces 365 µm ultraviolet light at 3 mW/cm2, which is what we used in the clinical trial,” he says. “It comes with two kinds of riboflavin. Photrexa Viscous is the standard riboflavin solution we use in cross-linking; it’s used for initial riboflavin loading and during UV exposure. The other formulation is Photrexa, which is a hypotonic riboflavin without dextran, used to induce corneal swelling. Before starting the UV light, you want the pachymetry measurement to be 400 µm or more, because if the cornea is too thin, the riboflavin-UV interaction could potentially have a toxic effect on the endothelium. If the cornea isn’t thick enough, you use the Photrexa to swell it before UV exposure.

“The first step is a 9-mm-diameter removal of the epithelium, done according to the surgeon’s preference,” he continues. “I delineate a 9-mm area with an optical zone marker and then use either a bird bath or a pledget of 20-percent ethyl alcohol to loosen the epithelium; then I remove it with a cellulose sponge and spatula. At that point you apply Photrexa Viscous every two minutes for a total of 30 minutes. Obviously, you have to have the speculum in for epithelium removal, but I like to take the speculum out while putting in the drops so the cornea doesn’t dehydrate and become thinner. Then I measure the thickness using ultrasound pachymetry. If the cornea is over 400 µm, I proceed; if not, I apply the hypotonic Photrexa riboflavin every 10 seconds for two minutes, with the eye closed between drops. If the cornea has still not reached 400 µm, I again apply the hypotonic Photrexa riboflavin for further counts of two minutes.

“Typically, most patients who are under 400 µm will swell to 400 µm within one or two sessions of Photrexa, although you can continue beyond that,” he notes. “I have not had any patients who were unable to swell adequately. The most important thing is to avoid selecting patients whose corneas are very thin at the outset. If a patient initially has a 280-µm cornea with the epithelium intact, he’s not a candidate for cross-linking.”

|

| Avedro’s KXL cross-linking system, currently approved to treat progressive keratoconus and ectasia. |

Dr. Hersh says you will almost always have good riboflavin uptake. “However, you want to confirm that you have stromal saturation at the slit lamp, especially when you’re just starting to perform this procedure,” he says. “Using the cobalt blue filter, you should see green spread homogeneously throughout the cornea. Also, you should see anterior chamber flare from the riboflavin. That’s riboflavin that has made it into the anterior chamber, which denotes that you have full-thickness saturation.

“Once the cornea is at least 400 µm thick and is saturated with riboflavin, you have the patient look up at the KXL system’s UV light unit and you center it on the x,y and z planes,” he says. “The patient gazes at the fixation light for the next half hour. During that time you continue to give the riboflavin dextran solution every two minutes. Once that’s completed, the procedure is done. Then we apply antibiotic, corticosteroid and a bandage contact lens. We check the patient on day one to make sure everything is OK, and on day four or five to make sure the epithelium has healed; then we remove the contact lens. We continue antibiotic drops for a week and taper the corticosteroid drops over the course of two or three weeks. This is essentially the same as the Dresden protocol, on which the clinical trial was based.”

Who Gets Better Outcomes?

“In my practice we’ve done studies looking at which patients are better candidates,” says Dr. Hersh. “We looked at three concerns. First, is stability the same for every patient? Second, who gets a better topographic result and who tends to fail the treatment and continue progressing? Third, which patients have a better chance of losing or gaining vision?

“The FDA clinical trial, which was placebo-controlled, showed that there was a significant difference in the change in the maximum keratometry as measured by topography—i.e., the height of the cone—between treated and untreated eyes,” he continues. “At one year, patients who had progressive keratoconus by the criteria of the study improved their topography by 1.6 D, while as expected, untreated patients continued to worsen.

“We also found that there was a modest overall improvement in BCVA and UCVA in the treated eyes, about one Snellen line or so,” he says. “In our own studies, unrelated to the FDA approval, we found that about 25 percent of corneas flattened by 2 D or more, and that patients who had keratometry of 55 D or more at the cone peak had a greater chance of being in this improvement group. However, both groups had an equivalent chance of remaining stable over time.

“With regard to correctable vision, most patients remained stable,” he says. “However, about 20 percent—the patients with worse topography, i.e., 55 D or more—improved their correctable vision by two or more Snellen lines and were five times more likely to improve their topography. In terms of acuity, patients who were 20/40 or worse before treatment were about five times more likely to improve their vision by two or more lines than patients who were better than 20/40.”

Potential Complications

“This is a relatively straightforward procedure; there aren’t many mistakes doctors can make,” notes Doyle Stulting, MD, PhD, director of the Stulting Research Center at Woolfson Eye Institute in Atlanta, professor of ophthalmology, emeritus, at Emory University and adjunct professor of ophthalmology at the Moran Eye Center. “The risks involved with this procedure are not zero, but they’re relatively small and the benefits are significant. Most of the complications that can occur are related to epithelial removal.”

“Theo Seiler published a paper that lists many of the problems you could potentially run across,” says Dr. Rubinfeld.1 (That study, involving 117 eyes of 99 patients, reported that 2.9 percent of eyes had lost two or more Snellen lines at 12 months. No patients had a severe complication, although the authors acknowledge that such complications have been reported at meetings.) “Regrowth and healing are generally compromised in steeper corneas and corneas with ocular surface disease,” he notes. “Scars, infections, haze and other problems can also occur. For that reason it’s important to look for signs of dry eye, blepharitis and other conditions that can com-promise the ocular surface.

“Dr. Seiler’s paper also shows that the steeper the cornea, the more likely the patient is to have either a poor response to the treatment or an adverse event,” he continues. “His study found that a preoperative maximum K-reading less than 58 D may reduce your failure rate, so if your patient has a very steep cone, that’s a reason to be particularly attentive to any ocular surface issues and postoperative epithelial healing. He also found that restricting patient age to younger than 35 years may substantially reduce the complication rates, so older patients may also require extra postoperative follow-up. But ultimately it’s important to remember that the safety profile of epi-off corneal cross-linking is markedly better than the safety profile of corneal transplantation.”

Off-label Uses for CXL

Many uses for cross-linking that go far beyond the uses approved by the FDA are being explored outside the United States. In the meantime, some less-dramatic off-label uses may be of interest to U.S. surgeons:

| Managing Patient Expectations |

| Roy S. Rubinfeld, MD, MS, in private practice and a clinical associate professor at Georgetown University Medical Center, notes that surgeons need to set patient expectations regarding what cross-linking does and does not do and the timeline for the expected results. “Patients often think that any eye surgery is similar to either cataract surgery or LASIK, in which patients see markedly better the next day and have just one evening of scratchiness and irritation,” he says. “Standard epi-off cross-linking is nothing like that. There is significant discomfort that generally lasts for up to a week or more, with markedly reduced vision during the first few weeks or even months. “Patients also need to understand that cross-linking is not a cure-all for keratoconus,” he continues. “The major objective of cross-linking is to stop the progression of a disease that is causing them to lose vision and potentially need corneal transplantation. Furthermore, the timeline for all of this is months and years.” Dr. Rubinfeld also points out that the course of recovery may not be smooth. “In several studies of standard epithelium-off cross-linking, vision has been seen to actually drop off for months postoperatively, and then start to return to where it was before,” he says. “That makes it very easy for patients to become anxious, or to believe that it’s not working or was a mistake. With epi-off cross-linking, patients need a great deal of hand-holding, discussion about expectations and reassurance.” Peter S. Hersh, MD, FACS, clinical professor and director of cornea and refractive surgery at the Institute of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, notes that this is especially important when the patient has very good vision before treatment. “If a patient is starting with 20/20 or 20/25 vision,” he says, “the loss of a line because of epithelialization or corneal haze might be more noticeable to him.” —CK |

• Non-progressing patients. “At first we reserved this procedure for patients who had progressive keratoconus, which is what the current approval is for,” says Dr. Stulting. “We thought that people who were not going to progress wouldn’t get any benefit. But we’ve sometimes seen a significant benefit in terms of improved vision in patients we thought wouldn’t benefit from it. For example, doctors often assume that older patients with keratoconus are not likely to progress. However, we’ve seen 66-year-olds with significant progression over six months, and we’ve seen patients in their 50s whose uncorrected and corrected vision improved significantly after cross-linking.”

Dr. Rubinfeld acknowledges that the risk/benefit ratio may be different if the patient’s keratoconus isn’t progressing. “The reality, however, is that keratoconus is an unpredictable disease,” he points out. “Not treating is a bit like saying, ‘Well, you have glaucoma and your pressure is high, but we think you might have a couple of years before you start really losing your sight so we’re not going to treat you.’ That wouldn’t hold up in court, and when you put your head on the pillow at night, you wouldn’t feel great about it.

“If the surgeon believes that this off-label use is in the patient’s interest, he’ll need to have a discussion with the patient under scope of practice,” he adds. “The surgeon, of course, will be responsible for those choices.”

• Younger patients. “Some of the people who need this the most are fair-ly young,” says Dr. Rubinfeld. “It’s understandable to want to treat them before they start losing their sight. We’ve treated patients as young as 8 years old in our study with excellent results.”

“You want to do this procedure early on to decrease progression as soon as possible,” adds Dr. Hersh. “And, just as in the treatment of macular degeneration and other diseases, probably the earlier, the better.”

• Treating infectious keratitis. Dr. Rubinfeld notes that there have been some published studies on the use of cross-linking to treat infectious keratitis. “My personal experience with that, as well as our study group’s experience, has not been very compelling,” he says. “I would urge caution in considering the use of cross-linking in the setting of infectious keratitis.”

Dr. Stulting agrees. “We don’t have good evidence that it is superior to standard, routine treatment for infectious keratitis,” he says.

• Improving vision. “Ultimately, a bigger and more satisfying objective is to improve vision in keratoconus patients, not just stop the progression of the disease,” says Dr. Rubinfeld. “That’s why outside the United States it’s become common to perform cross-linking and topography-guided laser ablations together. Under institutional review board approval, we’ve done some of these cases. However, my personal experience, as well as that of some of my colleagues, is that this is a field in evolution. It seems to be more of an art than a science with currently available technologies. Also, adding PRK to cross-linking may cause the epithelial healing to be even slower and more critical.”

Dr. Rubinfeld says that there’s another, less invasive way to move in the same direction. “Since 2012, our group has been combining two noninvasive procedures on an investigational basis,” he says. “We use conductive keratoplasty to reshape the cornea and then use our proprietary trans-epithelial cross-linking technique to lock in the effect. We now have two-year data demonstrating that this approach not only stops the progression but markedly improves both UCVA and BCVA. It’s been extremely gratifying for the patients and surgeons.”

• Leaving the epithelium on. Dr. Rubinfeld is one of a number of surgeons working on versions of the protocol that do not require removing the epithelium. “The effective epi-on version of cross-linking has been in development since 2010,” he says. “Dr. Stulting, in the prestigious Binkhorst Lecture at the 2016 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery annual meeting, described the first long-term data. It showed that this proprietary, patent-pending treatment is as good as or better than the Dresden protocol, while markedly reducing the risk, discomfort and recovery time that would otherwise be related to removing the epithelium. This is clearly the next generation of cross-linking.”

|

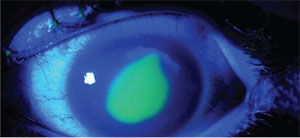

| Cross-linking with epithelial removal can lead to complications such as delayed epithelial healing and an infiltrate (pictured above, postop day two). |

A. John Kanellopoulos, MD, medical director of the Laservision.gr Clinical and Research Eye Institute in Athens, Greece, and clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU Medical School in New York, has been a pioneer in investigating alternative protocols and uses for corneal cross-linking. “Over the past 15 years we’ve introduced and practiced—internationally—fluences of 6, 10 and 30 mW/cm2,” he says. “We’ve also used techniques such as combining cross-linking with a partial topography-guided PRK, known as the Athens Protocol; we’ve used 10 mW/cm2 for 10 minutes with in-situ placement of the riboflavin in a femtosecond-laser-created corneal pocket; and we’ve used 30 mW/cm2 for 90 minutes as an adjunct to routine LASIK in high-risk myopic and all hyperopic cases. The latter approach was recently reported to increase biomechanical strength in the underlying LASIK stroma by 120 percent, ex-vivo.”

Despite all the promising uses for cross-linking that go beyond the FDA approval, Dr. Kanellopoulos believes it’s prudent for American physicians to initially adhere to the approved protocol. “The epi-off procedure is not without potential complications such as infection, melts, inflammation and potential scarring,” he says. “I think clinicians should become proficient with the standard technique before attempting to engage in off-label applications. All of those techniques will probably receive FDA approval at some point. It would probably be wise to wait until then to use them in the United States.”

Strategies for Success

Surgeons offer these pearls to help cross-linking novices get good results and avoid complications:

• Make sure that referring doctors don’t think this is a refractive procedure. “Referring doctors who are not well-acquainted with the procedure may contribute to patients’ incorrect expectations,” notes Dr. Hersh. “A few cross-linking patients may see better, but the purpose of cross-linking is stabilization of the progression of keratoconus, not giving the patient better vision.”

• If you diagnose a patient with keratoconus, refer the patient for cross-linking right away. Dr. Stulting says new patients with keratoconus are referred to him every week, but many doctors wait until the patient is on the verge of needing a transplant before making the referral. “Even after educating our referring doctors that referral is appropriate when someone is first diagnosed, I still get patients sent to me as a last resort when they can no longer wear a contact lens,” he says. “The referring doctors seem to think that corneal collagen cross-linking will somehow keep the patient from needing a graft, but that’s not the case for advanced disease.

“I see many keratoconus patients who are in their teens,” he continues. “I tell the parents about cross-linking and they say, ‘You mean you have a treatment that will keep our child’s vision from getting worse? Why didn’t my doctor tell us about this three years ago when my child’s vision was much better?’ More and more, I’m having trouble answering that question. Now that the technology is approved, it’s going to be impossible to explain a late referral. I think it’s just a matter of time before litigation and established standard of care forces the adoption of topography as a part of normal childhood eye examinations. It certainly should be done for patients who are myopic, astigmatic or have corrected visual acuity less than 20/20.”

• When starting out, choose corneas that are at least 350 µm thick before treatment. “You don’t want the cornea to be overly thin, because you won’t be able to swell it to 400 µm,” says Dr. Hersh. “In the clinical trials, we included patients down to 300 µm and used the swelling technique to get them to 400 µm. But in my own practice, I’ve found that it becomes difficult to reach 400 µm when the cornea starts below 350 µm.”

• Evaluate postoperative epithelial healing at the slit lamp early on. “Epithelial irregularity can diminish vision,” Dr. Hersh points out. “If you see an indication that the healing is irregular, be sure to address conditions such as dry eye and blepharitis aggressively.”

• If you see delayed epithelial closure postoperatively, consider removing the bandage contact lens. “Once treated with cross-linking, patients need to be followed fairly closely until the epithelial defect closes, which typically occurs during the first week,” says Dr. Stulting. “We learned early on that if we see delayed epithelial closure in these patients, particularly with persistent epithelial defects over the apex of the cone, we need to remove the contact lens, even though the epithelium hasn’t closed yet. The contact lens itself can interfere with epithelial closure.”

• Don’t let the patient resume contact lens wear until the ocular surface is completely healed. “The key to resuming contacts after cross-linking is ensuring that the ocular surface is completely healed,” says Dr. Hersh. “It should have regained its preoperative smoothness and integrity to avoid renewed injury or infection. We typically resume contact lens wear at the one-month follow-up.”

• Expect to see some corneal haze at the slit lamp for the first few months in some patients. “In our own clinical trial most cross-linking patients had a course of corneal haze that dissipated back to baseline by 12 months,” notes Dr. Hersh. “It typically doesn’t trouble the patient, but you can see it at the slit lamp. It begins as a generalized haze, like a dusting of the cornea, and evolves to the demarcation line, which we believe indicates the depth of the cross-linking, typically 250 to 300 µm deep. Nothing needs to be done to address the haze, unless it’s unusual; just provide general care for the ocular surface.”

What’s Next?

Although American surgeons are excited about finally having access to cross-linking, there are mixed feelings about still being behind the rest of the world, given the limitations of the approval.

“The procedure that’s been approved in this country is almost a decade and a half old,” notes Dr. Stulting. “Many improvements to the procedure have been proposed, and some have been found to be effective, but because of the delay in FDA approval we aren’t able to take advantage of them in this country. I’m afraid that alternate versions of the procedure will not be approved any time soon. Cross-linking has orphan designation, so Avedro is protected from competition for seven years, and there’s little motivation for them to invest millions of dollars in obtaining approval for an advanced technique before the approved one becomes widely utilized.”

“The FDA-approved system from Avedro is a great device,” says Dr. Kanellopoulos. “We’ve used it in Europe since 2010. However, it’s unfortunate that higher fluences of 6, 9, 18 and 30 mW/cm2 are not yet available; that would widen the possible techniques and indications. The worst thing, in my opinion, is the obligatory use of adjunct dextran-diluted riboflavin, because it causes significant dehydration and thinning of the tissue during soaking. Most available solutions internationally are now saline-based. We switched to saline back in 2004.”

Despite its limitations, Dr. Stulting says he still believes the approved procedure is an important tool for American surgeons to have. “There’s good data from Oslo, Norway, showing the value of the procedure,” he says. “At Oslo University Hospital, cross-linking was implemented almost a decade ago. They saw a 53-percent decrease in their incidence of corneal transplantation for keratoconus over a seven-year period. In the United States, the rate of corneal transplantation increased 19 percent over the same time period. The approved procedure may not be the best procedure, but it’s certainly better than nothing.”

“Research is going on that will make this procedure safer, better, more comfortable, less invasive and more predictable,” adds Dr. Rubinfeld. “There’s plenty of reason for optimism.” REVIEW

Dr. Hersh is a consultant for Avedro. Dr. Rubinfeld has ownership equity in CXL Ophthalmics and is managing member and president of CXLUSA. Dr. Kanellopoulos is a consultant for Avedro and Alcon. Dr. Stulting has no financial interest in any product mentioned.

1. Koller T, Mrochen M, Seiler T. Complication and failure rates after corneal crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:1358–1362.