THE IDEA OF USING NONPENETRATING SURGERY TO LOWER INTRAOCULAR pressure has been around for a number of years. Because it offers such advantages as an excellent safety pro-file and quick recovery, many early adopters of new technology have now done hundreds of cases, working to perfect the art and science involved and generating substantial literature. Many of these surgeons now only resort to trabeculectomy when a problem such as angle closure or neovascular glaucoma can't be treated with a nonpenetrating technique.

Despite its established history, however, nonpenetrating surgery still has a long way to go before being widely adopted; only about one-fifth of the glaucoma surgeons in the United States have tried it. In discussing this with other specialists, I've noted that a handful of reasons are commonly offered to justify a wait-and-see attitude. Here, I'd like to discuss those reasons and offer my perspective.

Today, there are multiple variations of nonpenetrating surgery. The two most often used are viscocanalostomy, which is intended to shunt aqueous back into Schlemms' canal, dilating it without a bleb; and deep sclerectomy, commonly performed with the use of an adjunctive implant such as the AquaFlow (Staar Surgical) or collagen wick.

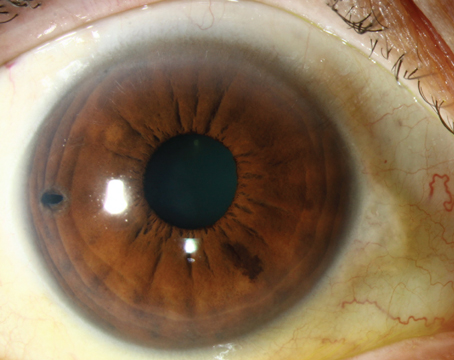

|

| Peeling of the inner wall of Schlemm"s canal enhances outflow and improves results. |

Is It Effective?

Most surgeons would probably agree that if our pressure targets are in the high teens, let's say between 15 and 18 mmHg, then any type of nonpenetrating surgery works just fine. However, because of the initially slower flow rate, many glaucoma specialists have concluded that these surgeries don't work as well as trabeculectomy and may not be able to bring IOP down to targeted levels. In fact, there are distinct variations between the different types of non-penetrating surgery, each of which has its own efficacy profile.

Three options have helped make it possible to titrate nonpenetrating surgeries and achieve lower pressures when necessary:

• Implants. These procedures involve removing a block of scleral tissue, creating a sort of bleb within the sclera. Studies have shown that to achieve lower pressures, the use of an implant is required to hold the bleb open and maintain the intrascleral lake.1,2

• Mitomycin-C. Like trabeculectomy, these procedures are affected by wound healing, which varies from person to person. High-risk eyes which tend to scar down can be especially problematic. Mitomycin-C gives us some control over this factor.

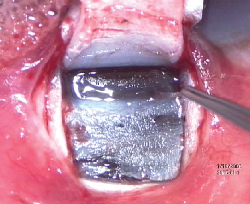

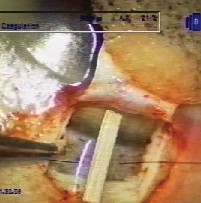

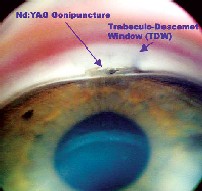

|

| Left: An intrascleral implant such as the AquaFlow collagen wick improves the success of NPGS. Right: Post-Nd:YAG laser goniopuncture of the trabeculo-Descemet window. |

• Laser goniopuncture. During the initial nonpenetrating surgery, we leave a very thin membrane, called the "trabeculo-Descemet window," creating a slow flow of aqueous from the anterior chamber. This causes pressure reduction, but not the rates of hypotony or other complications seen with trabeculectomy.

If the pressure still isn't low enough, we wait until the eye has sufficiently healed and apply laser goniopuncture, increasing the outflow by converting into a penetrating procedure. (This is similar to laser suture lysis with trabeculectomy, where we cut the scleral flap sutures to obtain more flow postoperatively, effectively turning trabeculectomy into a full-thickness procedure.) In our practice we probably use laser gonioscopy 40 to 50 percent of the time, anywhere from two weeks to two years later.

Doing this converts nonpenetrating surgery into a penetrating procedure. However, it does so after the first couple of weeks—the period when hypotony and flat chambers are a danger. I think of it as an ultra-guarded, two-stage trabeculectomy that's safer and more predictable.

With the use of these three adjuncts—an implant, mitomycin-C, and laser goniopuncture—we can achieve lower pressures while retaining the value of a nicely controlled pressure reduction in the early and mid-postop period. This is more effort than doing a simple procedure, but the safety and lower rate of complications are, in my opinion, a worthwhile trade-off.

Is It Too Difficult?

Many surgeons still express the concern that nonpenetrating surgery is too difficult to perform relative to the benefits it offers. To a large extent, this perception has resulted from the complications that some surgeons encounter when they first try to perform the surgery. Indeed, many specialists in tertiary-level environments who only deal with high-risk eyes aren't willing to try nonpenetrating surgery because of the risks and complications that may be associated with their first 10 cases.

However, we need to ask: Since when is something being hard a reason not to do it? Mastering difficult procedures is part of our job. (Switching to phaco was certainly no walk in the park for most surgeons.) Those who have gone through the learning curve with nonpenetrating surgery have continued to do it and have had much success with it. Indeed, most have become proponents of it.

In my experience, complications with these procedures are not any more serious than complications of trabeculectomy, even during your first 10 cases. My philosophy, which I've shared in courses I've taught on this subject at the American Academy of Ophthalmology and American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery meetings, is this: Although nonpenetrating surgery may be more difficult to perform than trabeculectomy, and you may have more complications during your first 10 cases, you'll be comfortable proceeding if you already know how to manage those complications. When surgeons learn to do cataract surgery using phacoemulsification, knowing how to convert to an extracap if a problem arises makes a big difference. (In the case of nonpenetrating surgery, Plan B is basically converting to trabeculectomy.)

Once most surgeons have gone through the learning curve, they adapt quickly and have excellent success with this type of surgery.

Does the Evidence Support It?

Many surgeons still express concern that the literature hasn't provided sufficient evidence for the benefits of nonpenetrating surgery. However, at this point more than 300 peer-reviewed studies have reported on the success rate of these techniques (for some examples, see the suggested reading list at the end of this article) and more reviews and new data will be published in the coming months and years. At this point, I think it's fair to say that the supporting evidence in the literature is substantial.

We've also just finished two randomized studies of our own, each involving about 75 patients, making a direct comparison between nonpenetrating surgery and trabeculectomy. We're currently reviewing our two-year results, and hope to publish both studies by the end of the year.

Despite the concerns some surgeons have, nonpenetrating surgery has become more widely accepted, particularly in Europe. I often hear from doctors who have started using these procedures and are very happy with the results they're getting.

| Who's Doing It? |

| In a poster at this year's ARVO meeting in Fort Lauderdale, Rick E. Bendel, MD, who practices at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., presented the results of a confidential survey of American Glaucoma Society members regarding their use of nonpenetrating glaucoma surgery. The doctors were asked if they performed viscocanalostomy and/or nonpenetrating deep sclerectomy, and what their experience has been with the procedures. Eighty-two members responded. • Sixteen percent (13 out of 82) said they perform some form of nonpenetrating surgery. • Nine of the 13 surgeons who use nonpenetrating surgery (69 percent) only perform one procedure. Four of the nine said they only do deep sclerectomy (three with the AquaFlow system, one with no implant); the other five only do viscocanalostomy. • Of the responding surgeons who use both procedures, all used the Aqua-Flow implant, one with mitomycin-C, when performing deep sclerectomy. • The number of nonpenetrating procedures performed per surgeon ranged from two to 150 cases per year. Nonpenetrating procedures were reported to be 5 to 15 percent of all glaucoma surgery performed in their practices. • Seven of the 82 respondents (8.5 percent) said they had performed the procedure at one time but no longer do. Reasons given included not being impressed with the extent of intraocular pressure reduction, unpredictable failures, the need for repeated postoperative laser goniopuncture, and limited indications for the surgery. |

It's an exciting time to become involved in this highly promising form of glaucoma surgery.

Dr. Ahmed is a fellowship-trained glaucoma, cataract, and anterior segment surgeon practicing in Toronto. He is assistant professor at the University of Toronto, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Utah, and is director of the upcoming third International Congress on Glaucoma Surgery that will take place in Toronto in May 2006.

SUGGESTED READING

1. Shaarawy T, Mermoud A. Deep sclerectomy in one eye vs deep sclerectomy with collagen implant in the contralateral eye of the same patient: Long-term follow-up. Eye 2005;19:3:298–302

2. Shaarawy T, Nguyen C, Schnyder C, et al. Comparative study between deep sclerectomy with and without collagen implant: Long term follow-up. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88:1:95–8.

3. Mermoud A, Schnyder CC, Sickenberg M, et al. Comparison of deep sclerectomy with collagen implant and trabeculectomy in open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:3:323– 31.

4. Chiou AG, Mermoud A, Hediguer SE, et al. Ultra-sound biomicroscopy of eyes undergoing deep sclerectomy with collagen implant. Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80:6:541–4.

5. Stegmann R, Pienaar A, Miller D. Viscocanalostomy for open-angle glaucoma in black African patients. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25:3:316– 22.

6. Luke C, Dietlein TS, Jacobi PC, et al. A prospective randomized trial of viscocanalostomy versus trabeculectomy in open-angle glaucoma: a 1-year follow-up study. J Glaucoma 2002;11:4:294–9.

7. Gianoli F, Schnyder CC, Bovey E, et al. Combined surgery for cataract and glaucoma: phacoemulsification and deep sclerectomy compared with phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25:3:340– 6.

8. Shaarawy T, Nguyen C, Schnyder C, et al. Five year results of viscocanalostomy. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87:4:441– 5.

9. Johnson DH, Johnson M. Glaucoma surgery and aqueous outflow: how does non-penetrating glaucoma surgery work? Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120:1:67–70.

10. Johnson DH, Johnson M. How does non-penetrating glaucoma surgery work? Aqueous outflow resistance and glaucoma surgery. J Glaucoma 2001; 10:1:55– 67.

1. Sunaric-Megevand G, Leuenberger PM. Results of visc1ocanalostomy for primary open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 132:2:221– 8.

12. Ambresin A, Shaarawy T, Mermoud A. Deep sclerectomy with collagen implant in one eye compared with trabeculectomy in the other eye of the same patient. J Glaucoma 2002; 11:3:214–20.

13. Shaarawy T, Mermoud A. Deep sclerectomy in one eye vs deep sclerectomy with collagen implant in the contralateral eye of the same patient: long-term follow-up. Eye 2005; 19:3:298– 302.

14. Shaarawy T, Mermoud A. Deep sclerectomy in one eye vs deep sclerectomy with collagen implant in the contralateral eye of the same patient: long-term follow-up. Eye 2004 Q20 .

15. Tanito M, Park M, Nishikawa M, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes of combined viscocanalostomy and cataract surgery with combined trabeculotomy and cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2002; 134:4: 513– 20.

16. Carassa RG, Bettin P, Fiori M, et al. Viscocanalostomy versus trabeculectomy in white adults affected by open-angle glaucoma: a 2-year randomized, controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:5:882–7.

17. Shaarawy T, Karlen M, Schnyder C, et al. Five-year results of deep sclerectomy with collagen implant. J Cataract Refract Surg 2001;27:11:1770– 8.