The Light Adjustable Lens (RxSight) has been in clinics around the country for a few years now, following its FDA approval in late 2017. Many surgeons have touted the advanced-technology lens for its ability to accept lens power modifications after implantation. The three-piece monofocal lens is implanted like any other monofocal, making the surgical aspect simple to adopt.

The company, RxSight, is still innovating. First-generation lenses required patients to wear UV eye protection at all times before the final lock-in treatments. Vance Thompson, MD, of Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, who was an investigator in the LAL’s FDA monitored trials, says that patients no longer need to wear UV protection while indoors because of the LAL’s new ActivShield technology, which prevents ambient UV light from tampering with the lens power before or between adjustments and lock-ins. He notes that “in theory, patients shouldn’t have to wear UV-protection goggles when outdoors but for now we’ve been recommending they do until their final lock-in.” He adds that this advancement has helped to increase doctor and patient comfort.

As you know, with adjustments and lock-ins, the LAL requires more work than most other IOLs. Amir Marvasti, MD, of Coastal Vision Medical Group in Orange County, California, compares the LAL practice experience to a combination of cataract surgery, general ophthalmology and LASIK. “The LAL experience for the surgeon feels similar to the situation of a presbyopic patient with a low prescription who needs two or three LASIK treatments to get them to the finish line,” he says. “The refraction and dilation feel like the preop process of LASIK, and patients expect a LASIK-like outcome.”

From LASIK-like preop testing and refractions to purchasing new technology and accommodating additional postops for adjustments and lock-ins, the process is involved. Elizabeth Yeu, MD, of Virginia Eye Consultants in Norfolk says the LAL is an exciting technology but one that wasn’t the best fit for the flow of her current practice. “With careful preop testing, we can achieve very precise results in a majority of our patients. I definitely see the benefits of LAL, especially for tweaking monovision outcomes and for post-refractive surgery surprises. But, in my current clinical practice, the multiple postoperative visits are a little complicated to manage for both the patients and our referring ODs,” she says. “I do think that some form of adjustable IOLs is the future if the lenses could be indefinitely tweaked or if the platform could be changed from say, monofocal to an EDOF.”

Whether they choose to offer the LAL or not, physicians agree that the LAL is an exciting addition to the cataract surgeon’s toolbox and one that heralds a new wave of adjustable technology—but questions may remain. What do these additional postop visits look like? What type of scheduling works best? How will this affect clinic volume? Is it worth it? Here, several cataract surgeons discuss their experiences incorporating the Light Adjustable Lens into their practices and share the adjustable technologies in the pipeline they’re looking forward to.

|

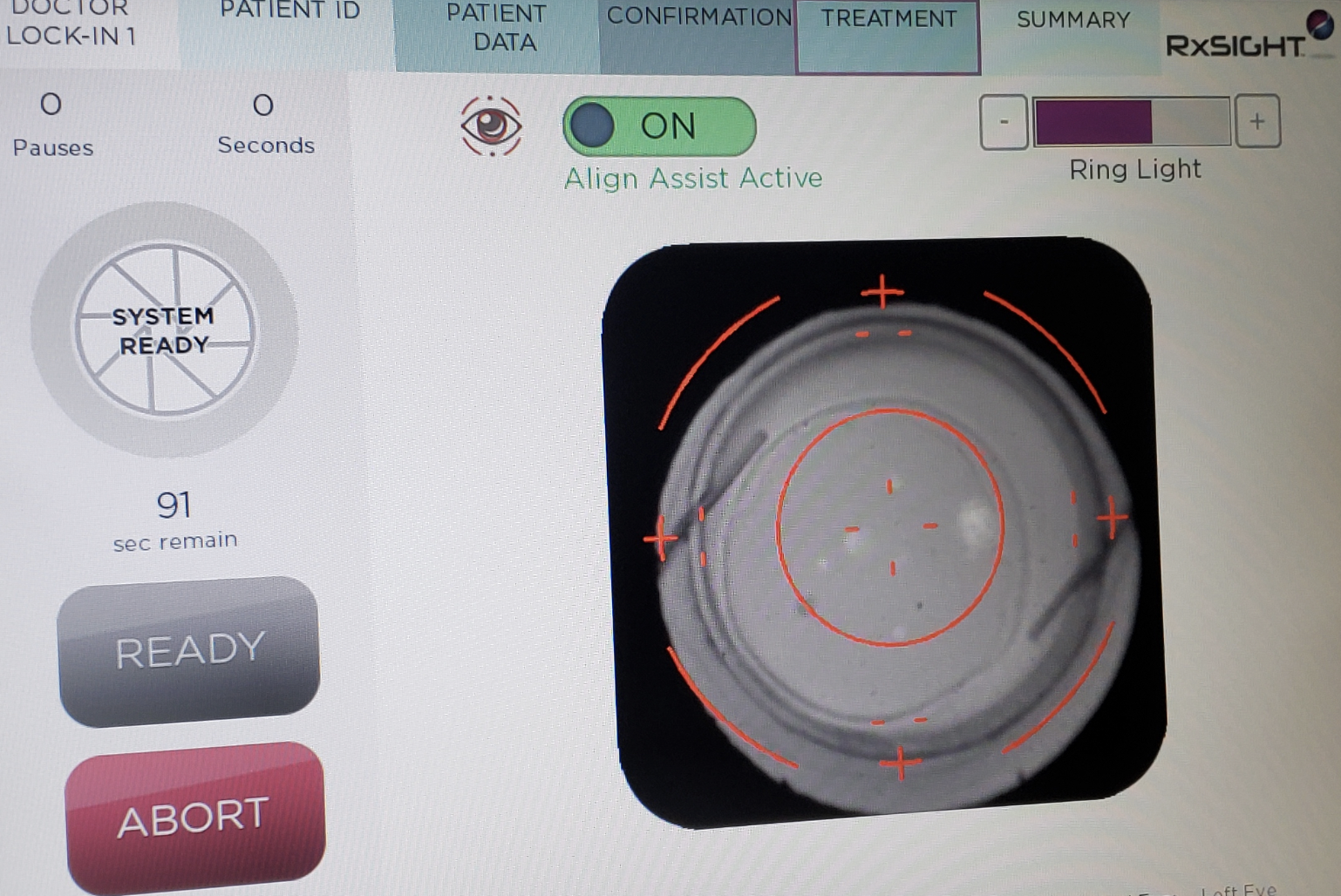

| The Light Delivery Device screen just before initiation of a treatment. Patients typically undergo three light adjustments and two lock-ins, but some patients require fewer treatments. (Courtesy of Bryan S. Lee, MD, JD.) |

Patient Education

Some surgeons say they enjoy the simplicity of the preoperative discussion about lens selection and refractive outcome with the LAL since the lens’s customizable nature removes some of the burden of lens choice with regard to sacrificing visual quality for increased visual range.

“With multifocals, we spend a significant amount of time explaining lens technologies to patients, deciding who will like what type of lens (knowing there are positives and negatives to each one) or who will do well with a mix-and-match strategy,” says John Vukich, MD, of Summit Eye Care of Wisconsin in Wauwatosa. “Multifocal lenses require giving up something and the unhappy patients are truly a challenge.”

Dr. Vukich says he’s had far fewer unhappy patients since he began implanting the LAL. He frequently offers LAL patients a blended-vision strategy. “Patients can try it on for size so you don’t have to choose what you think they might like,” he says. “Let them live with it for a while and then perform the adjustments based on their feedback. It becomes an iterative process in which the patient is a participant. That adds a great deal of not only satisfaction but patient confidence in the process.”

While the initial conversation about choice of lens may be simpler in some ways, there are still adjustment decisions to be made after the surgery. “Some patients have trouble making up their minds about their goal or target, and that can cause delays in the light adjustment treatments,” points out Bryan S. Lee, MD, JD, of Altos Eye Physicians in Los Altos, California. “Other times, we need to treat dry eye to get a cleaner refraction. It’s a good idea to have your team on the same page so everyone understands that there’s some flexibility needed with these patients. You might have to push things back by another week.”

As with any lens, but particularly with a premium lens marketed as “customizable,” setting patient expectations with thorough education and “underselling” can help guard against unhappiness. “I like patients to understand the variables of lens implant healing after cataract surgery and how that can affect their vision,” Dr. Thompson says. “I explain to patients that cataract surgery isn’t as accurate as LASIK, and I tell them why. When they finish our [practice’s] education, they understand the variables of effective lens position and incisional healing and how they can negatively affect the accuracy of the result. I go on to explain how with every other implant it’s not unusual for me to say that ‘I wish I had known your healing was going to lead to the blur without glasses you’re experiencing because then I would have put in a different power implant. With the LAL that’s less of an issue because when the healing has stabilized, we simply change the power of the implant to the power meant for you and that’s why it’s [incredibly accurate].’

“When we start talking about the LAL’s LASIK-like accuracy, patients almost hear the word ‘perfect,’ ” continues Dr. Thompson. “That’s why it’s so important to set up expectations. Some patients may still need to wear glasses for viewing certain things.”

“The art of sales isn’t something that’s taught in medical school or during residency, and it’s not a natural transition for most surgeons,” Dr. Vukich says. “It’s very hard to take that step. However, I’ve learned that the way I present things is ultimately how I’m providing information, and the patient needs to make a decision. Don’t oversell the technology but be honest about the strong outcomes. At the end of the day, a premium lens is a product you sell. What I’m selling isn’t something that doesn’t have value. I’m providing the opportunity for a technology the patient might not have known even existed.”

|

| Amir Marvasti, MD, of Coastal Vision Medical Group in Orange County, California, performs a light treatment on an LAL patient in his office. (Courtesy of Amir Marvasti, MD.) |

Navigating the Postops

The first months after receiving the LAL involve more visits than the average cataract experience, Dr. Thompson explains. “In addition to the healing visits at one day and one week, there are the light adjustments and lock-in visits,” he says. “As with traditional cataract surgery where there’s a period of waiting for the patient’s refractive error to stabilize before prescribing glasses, LAL patients must wait four or five weeks to stabilize before undergoing light treatments.”

“There’s no question that the LAL adds chair time,” agrees Dr. Vukich. “Adjustment visits aren’t simple ‘how are you doing’ visits with the patient on their way in five minutes. These patients have to be refracted and dilated and then treated.”

“Some patients are slow dilators,” Dr. Lee adds. “Also, they have to dilate beyond what we need to see the retina and lens during a typical eye exam. For light adjustments, we really need patients to dilate all the way to the edge of the lens. Some patients dilate with one or two sets of dilating drops, and others take four or five sets. They take up a room and are there for quite a while. We learned not to start LAL patients too late in the day.”

“Typically, we do three light adjustments and two lock-ins, though sometimes the patient doesn’t need all five treatments,” Dr. Thompson says. “The Light Delivery Device performs a mathematical equation that ensures all the macromer (the unpolymerized polymer) in the lens is fully polymerized. That may take five treatments or fewer.”

Dr. Thompson says hand positioning for the light delivery is very intuitive. “It’s similar to if you were doing gonioscopy or YAG laser capsulotomy,” he says. “The learning curve is short because of that.”

At his practice, Dr. Thompson says it’s pretty unusual to perform more than two treatments in one week. “You should be able to do a treatment every two or three days, in theory, but we typically don’t push it to that limit,” he says. “We often do two treatments in one week, and the following week do another treatment and begin the lock-in process. If necessary, we do the final lock-in during the third week.”

Workflow Changes

Dr. Marvasti’s practice was among the first to offer the LAL. “We learned as we went, but I wish we’d had someone to give us advice,” he says. “Now you’re going from a patient who—apart from the day of surgery—you saw maybe three or four times for postop visits to a case where you’re going from preop and surgery to five, six—sometimes seven or more visits. Your office is going to get busier; your waiting room is going to get busier. Your wait time may increase if you don’t make changes at each stage. It’s almost like adding 10 to 20 percent volume to your clinic and to your optometrist’s clinic, so you have to prepare for that.”

Dr. Lee’s practice began offering the LAL soon after its approval, which also coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite pandemic disruptions, he says the slow-down in patient volume gave his practice the opportunity to try out different workflows for LAL patients. “Now, patients undergoing light adjustments tend to be scheduled first thing in the morning or the first slot of the afternoon,” he explains. “Our Light Delivery Device is in the same room where we have a lot of our other testing equipment, which is on the opposite side of the building from where we see patients. It’s more efficient for us to have these patients stacked up and ready to adjust, as opposed to being scattered throughout the day. We bring them over to the testing room and do light adjustments for two or three patients at a time.

“My partner does it differently,” Dr. Lee continues. “He does light adjustments after his OR days, so he comes back from the OR and has his patients already worked up and dilated. Each practice will have to figure out what works best in terms of integrating LAL patients into workflow.”

At Dr. Vukich’s practice, an optometrist refracts the patient at each light-adjustment visit and provides the discussion of the refractive outcome. “In some instances, they’ll have the machine programmed and I’ll come in and do the treatment. If the patient is seated and the treatment is already registered to the machine, chair time may be as little as three minutes, including a bit of chit-chat. This approach is very efficient, but it’s vital to have someone with the skillset of a quality refractionist who also understands patient relations. That’s the person you need to have in your office to facilitate.”

Dr. Thompson emphasizes the need to set up your team’s and referring doctors’ expectations for the LAL process. “You’re doing everything in a six- to eight-week period for these patients,” he says. “It’s important for the team members to prepare themselves.”

Since patients must return to the clinic so frequently within a short period of time, Dr. Thompson recommends working out a way to streamline these light-adjustment visits. “It’s not unusual for these to be two-hour visits,” he says. “We don’t want patients spending a lot of time in the waiting room. We streamline getting them back, getting their uncorrected vision checked, doing their manifest refraction and getting them dilated. We want to have that beginning step before dilation happen quickly because, as we all know, dilation can’t be sped up, and we want the pupil to dilate to at least 6.5 to 7 mm. In certain patients, additional dilating drops or even a pledget to hold the dilation drop on the eye longer may be needed. However, the light-adjustment process itself is only about five minutes, if you include double-checking data entry, alignment and the 60- to 90-second light delivery.”

|

| Adjustments are performed using the Light Delivery Device. Experts note that since some patients may take a while to dilate, it’s best to avoid starting LAL patients too late in the day. (Courtesy of Vance Thompson, MD.) |

The Right People & Tools

The surgeons we spoke with for this article say the LAL accounts for approximately 15 to 30 percent of their premium lens volume. Experts note that in a high-volume practice, in particular, the additional postops may require some other changes.

“You may need to add additional optometrists to your practice, depending on your LAL volume,” Dr. Marvasti notes. “Good refractionists are absolutely necessary. You’ll also have to decide how many Light Delivery Devices to acquire. If you’re a single-location practice, just one of the Light Delivery Devices is sufficient. But if you have multiple locations, at some point you have to make a decision: Do you just want one of these and have your patients travel or would you like one device per location?”

It’s also key to have a way of tracking patients’ light treatments. Dr. Marvasti’s practice uses a paper chart to track every patient’s progress as well as LAL-specific notes in their EMR system. “You need to keep track of many aspects, and this amount of information may not fit in a regular EMR visit or just be difficult to track,” he says. “What was the preop refraction? The one-week refraction? The two-week refraction? Was a contact lens trial for monovision done? If so, what was the result? What were the results for the first, second and third treatments?”

“For us, it’s pretty straightforward since we’re on paper,” Dr. Lee says. “What’s nice about the paper chart system is that it’s just two or three pages. We can easily flip back and see the entire time course. Apart from the numbers, it’s also a quick reminder of what the discussion was with the patient, why we planned the treatment a certain way and what the patient’s feedback was each time. I think it’d be much more cumbersome to do that with EMR.”

How Much to Charge?

How practices choose to price the LAL varies. Some practices charge more due to the additional amount of time and labor while others have opted to charge the same amount as they would for a trifocal or EDOF lens.

“We charge the same as we do for a trifocal or EDOF because it’s about the same number of visits in a year, just more condensed on the front end,” Dr. Thompson says. “The LAL has been a game-changer in our practice.”

At Dr. Vukich’s practice, he says they charge almost the same as what they charge for a multifocal lens. “Many practices charge more for the LAL because there’s more work involved,” he points out. “I want there to be a premium lens that’s the best choice for the patient—not a good-better-best option—and not a price-related decision.”

Dr. Lee’s practice charges more for the LAL than a trifocal because “it involves so much postop care and time.”

Dr. Marvasti says his practice initially priced the LAL as a presbyopia-managing lens with laser-assisted cataract surgery. Over the years, they increased the price by 10 to 15 percent to account for the additional visits and work involved with the lens. “The LAL price is an easy discussion with the patient compared to other presbyopia-managing lenses,” he explains. “With a trifocal, for instance, you’re telling the patient that the cost is related to their ability to read. With the LAL, it’s very easy for patients to understand why it would cost more given the amount of work that goes into each of the many visits. The real question is: ‘This is a monofocal. Why should I go through with this cost?’ That’s a whole discussion on the differences between an adjustable monofocal IOL and non-adjustable IOLs for a particular patient.”

Commitment

“The LAL is a great technology, but to be successful with it, you have to fully commit to making the necessary logistical adjustments,” Dr. Lee says. “Offering the LAL isn’t something you can do in a part-time fashion. It wouldn’t lend itself well to a roll-in roll-out model where you don’t own the device, but it comes to your practice on certain days. I think it’d be very hard to do that.”

He adds that it’s a full team effort. “Your scheduler, your front desk staff, your technicians, and your optometrists have to understand that there will be some major changes in patient flow and other areas. Everyone needs to understand why you’re adding the LAL, why the technology is so different and why it works the way it does.”

Dr. Marvasti advises prospective LAL surgeons who don’t already perform LASIK to consult with colleagues who have busy LASIK days. “See how they manage all their refractions or how many optometrists they have,” he says. “If you already do LASIK, you can use that as a model and apply it to cataract surgery. Overall, consulting with physicians who have been using the LAL or their office managers will help because you’ll have to change your templates and potentially add more staff. Whether or not you’re willing or able to do that is very important.”

What about surgeons who want to offer the LAL but feel their practice is already too busy? “Busy is not the same as productive,” Dr. Vukich says. “Realigning your priorities and how you allocate your time can be to your advantage economically and to the advantage of the patients you treat. Don’t just say, ‘Oh, I see too many patients the way it is now.’ Are those all the patients you want to be seeing? Are these patients who could maybe be seen by an optometrist instead for routine visits and follow-ups? Are you spending your time efficiently and productively? It’s not a numbers game in terms of the number of patients in your waiting area. It’s about quality versus quantity. A doctor who does 10 premium lenses compared with one who does 30 standard implants with no premium conversion wins every time.”

As a disruptive technology, the LAL’s initial incorporation into a practice can be challenging, but surgeons say the outcomes and the patient and staff enthusiasm are well worth the changes. “It’s been refreshing having so many happy patients,” Dr. Vukich says. “It’s easy to see everyone’s enthusiasm. Patients in the dilating area are talking about how great their vision is, and it boosts the morale of those about to get their first light adjustment and creates a general positive feeling throughout the clinic for the staff as well. It’s been a practice builder too. At the end of the day, if you’re delivering outstanding results, word gets out, and word of mouth is a major driver.”

Adjustable Technology In the Pipeline

The LAL is currently the only available adjustable lens technology, but experts are looking forward to a few others in development. Here are some in the pipeline:

• Perfect Lens. Perfect Lens technology uses low-level femtosecond laser energy to alter the hydrophilicity of a hydrophobic acrylic IOL’s polymer. It’s done in a pattern called “phase wrapping” that slowly builds a change in an IOL’s subsurface, effecting a change in the lens itself, explains Nick Mamalis, MD, of the Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah and member of the Perfect Lens advisory board. “It can make not only spherical but also toric corrections on the lens, so one could potentially place a multifocal pattern on the lens, if that’s something to be desired,” he says.

“This technology can also correct the power of a lens that’s been in the patient’s eye for quite some time,” he continues. “It could be done right after the initial surgery once the patient’s refractive changes settle down and they’ve got significant refractive error. But it could also change a lens that’s been in a patient’s eye for years, as long as the pupil dilates enough to provide a clear view of the lens itself.”

The setup is similar to that of femto cataract surgery, Dr. Mamalis says. “A special coupling lens is placed on the eye and then the laser will come in and focus. Once the focusing is done and the patient is set up and ready for surgery, the procedure itself takes just a couple of minutes. The laser treatment is usually done as a one-time procedure, but it could be done more than once, if a patient’s refraction changed years later.”

The Perfect Lens group has been conducting extensive laboratory research and reports that changes can be made within 0.1 D. “It’s very precise,” Dr. Mamalis says. “There have been multiple studies done on research eyes showing very accurate lens changes. The company was just beginning to do clinical studies outside of the United States when COVID hit, so there was a two-year delay in living human eyes, but they’re now in the process of conducting studies that will allow Perfect Lens to get a CE mark in Europe and eventually get FDA approved in the United States.”

• LIRIC. Laser-induced refractive index change (LIRIC) is in early stages. It could potentially induce power changes in an IOL, though now it’s currently being investigated for use on the cornea.

The technology, piloted by scientists at the University of Rochester and licensed to Clerio Vision, uses low-level pulsed femto laser energy to non-surgically alter the refractive index of certain materials and tissues such as the cornea, crystalline lens, intraocular lenses and contact lenses. According to the University of Rochester, this process doesn’t induce a healing or scarring response and can be customized to an individual’s exact wavefront error in the eye.1

You can read more about LIRIC in the February 2022 issue of Review and in the feature, “Refractive Procedures in the Pipeline”.

Dr. Thompson is a consultant and researcher for RxSight. Dr. Vukich is a consultant for RxSight and has been an investigator for RxSight in the past. Dr. Mamalis is on the Perfect Lens advisory board. Drs. Yeu, Lee and Marvasti report no related financial disclosures.

1. LIRIC – a new paradigm in refractive error correction. University of Rochester Medicine, Flaum Eye Institute. https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/eye-institute/research/labs/huxlin/projects/liric.aspx. Accessed March 9, 2023.