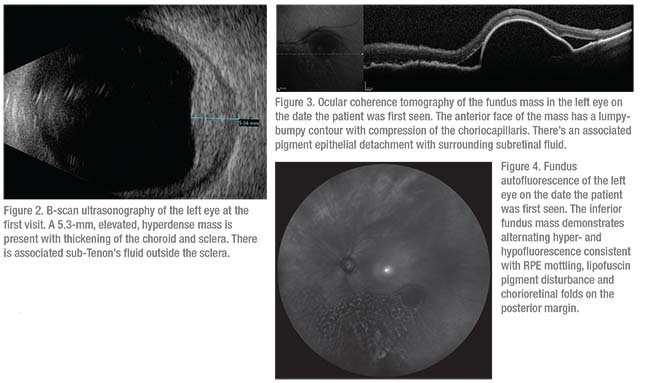

Further investigation was performed with ultrasonography, optical coherence tomography and autofluorescence. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated an echodense choroidal lesion measuring 5.3 mm in thickness with subtle lucency immediately outside the globe, lining the sclera (Figure 2). OCT revealed a mass with a “lumpy-bumpy” surface contour and compression of the choriocapillaris, a peculiar retinal pigment epithelium detachment and surrounding subretinal fluid (Figure 3). Fundus autofluorescence demonstrated alternating hyper- and hypofluorescence overlying the mass, suggestive of RPE mottling and perhaps lipofuscin pigment (Figure 4).

|

The presence of a non-pigmented fundus mass raised suspicion for choroidal metastasis or amelanotic choroidal malignant melanoma. An investigation for systemic malignancies was initiated and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was performed. Chest radiograph demonstrated linear scarring and atelectasis with no evident tumor. CT of the head and chest with and without contrast were normal and MRI of the abdomen revealed only fatty liver. A mammogram was within normal limits. FNAB revealed rare atypical epithelioid cells which were non-diagnostic.

|

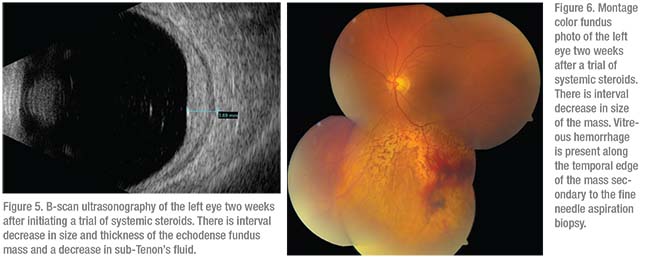

On re-examination and review of available data, particularly with her history of chronic headache and ocular “pressure feeling,” and the ultrasound features of echolucency rimming the posterior sclera (T-sign), the differential diagnosis was broadened to include scleritis. The OCT appearance of a lumpy-bumpy surface was consistent with metastatic disease; however, extensive systemic workup revealed no evidence of primary tumor. Posterior scleritis was highly considered as a potential diagnosis and a trial of systemic corticosteroids was begun with close follow-up. After two weeks of treatment consisting of prednisone 60 mg daily, there was reduction of the amelanotic mass from 5.3 mm thickness to 3.7 mm (Figure 5), along with improvement of symptoms and the appearance of the retinal pigement epithelium detachment (Figure 6).

Discussion

There is a broad differential diagnosis for an elevated choroidal mass, particular those that are amelanotic. In the present case, choroidal neoplasia remained an important and “must-not-miss” consideration in the differential diagnosis, including both primary and metastatic tumors. Malignant melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignant neoplasm in adults; however, clinicians should realize that choroidal metastasis is perhaps the most common intraocular malignancy in adults, particularly when considering all tumors.1 The mass discussed here had features suggestive of both amelanotic melanoma and choroidal metastasis, given the lack of pigmentation and fairly asymptomatic presentation. OCT was more consistent with choroidal metastasis in that the tumor demonstrated a lumpy-bumpy surface contour—a feature strongly suggestive of choroidal metastasis, effusion and inflammation, but not necessarily melanoma. In a series of 31 eyes with choroidal metastasis, the characteristic lumpy-bumpy anterior contour of the mass was present in 64 percent, and compression of the choriocapillaris in 93 percent. This lumpy-bumpy surface was identified in the current case, strongly biasing the evaluation towards metastatic disease.2

B-scan ultrasonography can also aid in identification of the underlying tumor. In this case, the mass was echodense, consistent with choroidal metastasis as well as inflammation and other tumors, whereas choroidal melanoma would typically reveal echolucency. With these concerning features, systemic evaluation for a primary malignancy was instituted. In a series of 520 uveal metastases, more than 66 percent of primary tumors identified were of breast- or lung-cancer origin.3 However, there were a substantial number of cases (17 percent) for which a primary malignancy wasn’t identified.3 In the present case, mammography and chest radiograph were unremarkable, as were additional systemic studies including MRI of the abdomen and CT of the brain.

In cases of intraocular tumors without a clear diagnosis from clinical examination and non-invasive studies alone, cytopathologic diagnosis via FNAB can be employed. This proves particularly useful in amelanotic tumors that can be difficult to distinguish between amelanotic melanoma and other neoplasms, as well as lesions concerning for metastases with an unremarkable systemic workup, as in our patient.4 In a review of 159 patients undergoing FNAB for intraocular tumors, 140 samples provided sufficient cytopathologic material for diagnosis with 100-percent sensitivity. The remaining 19 samples demonstrated a paucity of cells resulting in a decrease to 84-percent sensitivity.4 In our patient, FNAB revealed rare atypical epithelioid cells with insufficient quantity for immunological studies and cytopathological diagnosis. This prompted a reassessment of the case with broadening of the differential diagnosis, including inflammatory conditions such as posterior scleritis.

Posterior scleritis is a great mimicker of ophthalmic disease. Patients with posterior scleritis may or may not have a red eye, pain, peribulbar edema or other classic signs. Posterior scleritis can also present as serous retinal detachment, macular edema, optic nerve edema or annular choroidal detachment leading to acute angle closure, which are atypical findings for the classic case.5 Further hiding its detection, posterior scleritis can present with substantial pain, blurred vision, redness and/or significant vitritis, or be completely asymptomatic.5 In the current case, the patient noted left eye “pressure,” but didn’t classify it as pain. This initial piece of evidence can be less suggestive of neoplasia, but it should be noted that choroidal melanoma can occasionally cause pain. Choroidal metastasis, especially from lung cancer, can also produce pain, further complicating the diagnostic investigation.3,5

One of the most important imaging modalities in the evaluation of a fundus mass is ultrasonography. Along with measuring tumor thickness, ultrasonography allows for characterization of tumor echodensity. Unlike melanoma, which is typically echolucent, both scleritis and choroidal metastases are echodense. In closer examination, one can identify another feature of scleritis, the characteristic T-sign caused by sub-Tenon’s edema surrounding the optic nerve and posterior sclera that takes on a T-shaped configuration.5 Others have found the T-sign on B-scan ultrasonograpy to be useful for diagnosis of posterior scleritis, particular in those under suspicion for choroidal melanoma.6 In the present case, the T-sign was present in a different fashion as the sub-Tenon’s fluid was primarily seen outside the inferiorly located mass, rather than at the posterior pole around the optic nerve. Despite the classic appearance of the T-sign in posterior scleritis, a recent study of 114 patients with posterior scleritis found this sign in only 41 percent of patients.7 In that series, the most common ultrasonographic feature of scleritis was echodensity with thickening of the sclera and choroid as seen in our patient.7 B-scan ultrasonography can also be useful in identifying additional suggestive features of posterior scleritis including an eyewall thickness greater than 2 mm and scleral nodules.8

Once diagnosed, posterior scleritis is a treatable condition with oral or periocular corticosteroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, leading to improvement in pain and visual acuity. Despite variation in medications, anti-inflammatory therapy is the mainstay of treatment. In the aforementioned series of 114 cases of posterior scleritis, treatment ranged from topical corticosteroids to systemic immunomodulatory therapies such as mycophenolate and azathioprine.7 Most commonly, however, patients were treated with systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or systemic corticosteroids as in the present case.7 Across all specific treatments, the mean time to remission, which is defined as no disease activity 90 days after stopping all immunosuppressive treatments, was 210 days with a 15-percent risk of relapse.7 This risk of relapse wasn’t significantly different between idiopathic cases or cases found to be associated with other systemic inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid polyarthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.7

Posterior scleritis can have a multitude of presentations, allowing it to mimic other more common pathologies. Despite its rarity, posterior scleritis is an important consideration in evaluation of a fundus mass, especially in those cases without a clear diagnosis. In the present case, the patient’s amelanotic mass was echodense on ultrasonography, and an unremarkable FNAB and systemic workup made neoplasia less likely. With improvement in symptoms and remission with immunosuppressive treatment, posterior scleritis remains a treatable condition. Therefore, this case of a 73-year-old woman with an amelanotic fundus mass serves as a reminder of the importance of establishing a broad differential diagnosis. REVIEW

1. Recchia FM. Retinal and Choroidal Tumors. In: Fineman M, Ho A, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology (Wills Eye Institute): Retina. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.

2. Al-Dahmash SA, Shields CL, Kaliki S, et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of choroidal metastasis in 14 eyes. Retina 2014;34:1588-1593.

3. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, et al. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1265-1276.

4. Shields JA, Shields CL, Hormoz E, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected intraocular tumors. Ophthalmology 1993:100;1677-1684.

5. Benson WE. Posterior scleritis. Survey Ophthalmol 1988;32:297-316.

6. Shinisha DP, Elangovan S, Puri SK, et al. Unusual presentation of posterior scleritis. Health Sciences 2016;5:54-57.

7. Lavric A, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Majumdar PD, et al. Posterior scleritis: Analysis of epidemiology, clinical factors, and risk of recurrence in a cohort of 114 patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2016;24:6-15.

8. McClusky, PJ, Watson PG, Lightman S, et al. Posterior scleritis: Clinical features, systemic associations and outcome in a large series of patients. Ophthalmology 1999:106:2380-2386.