As noted last month in Part 1 of this article, the phenomenon of private equity firms buying ophthalmology practices has proliferated in recent years. Given the widespread nature of this phenomenon and the huge potential ramifications for a practice that undertakes such a partnership, doctors are asking a host of questions. In this article, two surgeons who have successfully partnered with private equity firms, and two consultants who have helped doctors navigate these waters, address 15 of the most often-asked questions.

In Part 1 of this article our experts discussed nine questions regarding the historical context of this phenomenon; the potential benefits and downsides of partnering with a private equity firm; and which kinds of practices are more likely to do well in this situation. This month, they address the six remaining questions, covering the ways in which a private equity deal is likely to impact your practice (as well as the field of health care), and steps you can take to ensure a positive outcome if you decide to proceed with a private equity deal.

10 How will these partnerships impact the care we provide our patients?

John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, points out that it’s early to predict the potential impact that private equity may have on patient care. “In my experience, there hasn’t been any change at all in how practices are run following private equity deals,” he says. “The private equity companies I’ve followed are being relatively hands-off. They’re trying to centralize some services, but I haven’t heard of any cases in which the private equity company has said to the doctor, ‘We don’t want you to have that updated laser,’ or, ‘We don’t want you to hire the techs that you need in the back office,’ or, ‘We think you should get out of this or that line of service because it’s not profitable.’

“We’re not seeing that type of granular encroachment, and we may never see it,” he continues. “The private equity companies are buying up practices they deem to be acceptable—or better—in terms of their current operations and their quality of care. They wouldn’t buy a practice otherwise. Remember: The private equity people are not in the medical business; they’re in the finance business. From what I’ve seen, they’re sticking to their jobs—they’re not trying to play doctor at all. Of course, there are exceptions. And that could change further down the line if some of the companies get in trouble, or if some of them decide that improving the practice is something they should be doing.”

Even if the private equity company doesn’t attempt to alter practice management, wouldn’t the fact that doctors are receiving a smaller salary discourage, for example, the purchase of a new laser? “First of all, it’s not a fixed amount of money that the private equity takes out of the practice,” Mr. Pinto explains. “Typically, the private equity company will take a percentage of earnings. So if the doctor who just got a really big check for his buyout feels that there’s a piece of equipment that he needs, both the company and the doctor will be paying for it. The doctor might still want to go ahead and buy that piece of equipment.”

11 How will lower salaries impact my practice?

In return for investing in the purchased practice, the private equity partner takes a share of practice profits. This means that at least some of the doctors in the practice will be taking home a smaller amount of money each year.

“Today, private equity companies are buying up practices at about six to eig

|

| Though a private equity company will have a say in how much you can spend on such things as new capital equipment, doctors say the companies often are OK with such purchases if they grow the business. |

ht times the practice’s annual profit—in some cases much more than that,” Mr. Pinto explains. “The reason a private equity company can do that is that they’re taking money from investors—money that’s leveraged and borrowed—in order to buy these practices, which they see as earning streams. These transactions are highly tax-favored, and the model works, seen strictly through the eyes of the private equity company. But the transaction leaves the acquired practice with fewer dollars available for doctors’ salaries.

“That’s a perfectly great tradeoff if you’re a senior doctor who is looking for a payout,” he continues. “The payout from a private equity transaction can be twice or more what you would get if you sold your practice to a fellow physician. For some clients, it’s a marvelous succession option to consider, but I think it’s going to leave others quite disappointed.

“For example, suppose your practice has a mix of older and younger doctors,” he says. “The senior doctors are going to be in the boardroom raising their hands and saying, ‘Let’s do this deal.’ The smaller salary in the years ahead won’t impact them as much because they’re taking their lump sum and retiring. That’s not the case for the younger doctors, who will have reduced earnings for years to come. That’s one of the built-in traps in this situation, and it’s just as much an issue today as it was in the 90s. That’s why I have mixed feelings about what I’m seeing right now.”

Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, managing partner at Minnesota Eye Consultants—now part of Unifeye Vision Partners—explains how his practice evaluated the cut in salary that would accompany proceeding with their private equity deal. “Our group has 10 partners,” he explains. “We sat around the table, and asked everybody to write down what they needed to make over the next decade to live comfortably. Eventually, we came to a consensus that we’d all be comfortable making X. We thought we might end up taking about a 30-percent reduction in income after the deal, but everyone still found the

|

numbers acceptable. Then we calculated how much practice profit would remain. If there was nothing left, private equity wouldn’t work, because they value the practice in terms of a multiple of residual earnings. As it turned out, there was money left over, so the deal could work.

“Interestingly, at the end of our first year, we appear to have only taken about a 15-percent reduction in income,” he adds. “That’s better than we expected. Of course, it’s possible that if the practice growth really takes off we might even earn back the money we’ve given up, thanks to increased profits. The hype is always that we’re going to grow, we’re going to expand our cash-pay opportunities, we’re going to do some additional marketing, we’ll do more premium IOLs, and so forth. However, that could turn out to be nothing more than hype, so you have to discount that possibility a little bit.”

12 Is this arrangement bad for the younger doctors in the practice?

Brett W. Katzen, MD, FACS, president of Katzen Eye Group, based in Baltimore, has been part of two successful private equity partnerships. He points out that how a private equity deal affects the younger doctors in a practice will depend on how the deal is negotiated. “In our deal, the younger doctors didn’t take a pay cut,” he explains. “We’ve always had an arrangement that doctors get a percentage of the revenue they bring in. If you’re an owner, you would also get a percentage of the profit made by the business. That percentage of the business’s profit is what the owners are investing in exchange for the cash and/or stock, so the owners are taking home less money.

“Our deal didn’t change what the employee doctors are earning at all,” he continues. “In fact, they should be incentivized to make more—and many of my doctors are making more now. My main cataract surgeon had his best year ever last year, partly because the private equity company invested so much in our infrastructure. The employee doctors earn the same percentage they did before, but now they have better patient flow and higher-quality instrumentation, so they at least have the potential to earn more than before.”

Dr. Lindstrom agrees that the private equity partnership can be a great way for a doctor close to retirement to cash out. “For an older doctor like me, it’s a great way to leave,” he says. “Our specific deal will allow a doctor to exit if he or she wants to, and the amount we leave with will be much greater than what our partners would have been able to pay. In theory, I could retire now; I’m one doctor out of 26, so it wouldn’t be an issue if I went away. But I decided to recommit and stay another five years through the next transaction.” (He notes, however, that no private equity company is going to buy a practice and let all of the primary revenue generators leave.)

What about the impact of the deal on the younger doctors in the practice? Dr. Lindstrom says that because of the way his practice’s deal was set up, it was arguably even a better deal for the younger doctors in the practice than for the doctors closer to retirement. “In addition to a cash payment, we made sure the younger doctors would be paid an adequate salary,” he says. “Meanwhile, let’s say you get a million dollars today, and you put that in a tax-deferred environment such as an IRA. If you’re getting 8 percent annual interest, that amount of money will double every 10 years. If you’re just starting out, you’ve got three doublings ahead, from one to two to four to eight million dollars. If you start with $2 million, you’re up to $16 million by the time you’re ready to retire. There’s no way a young doctor could save that much money in any other way. And along the way, if you need to borrow for your kid’s education, you can.

“Not only that,” he continues, “those doctors are going to get two or three bites of the apple as the group is resold, with more opportunities to invest. All of the younger doctors in our practice did choose to invest in the group, and they’ll have the chance for another recapitalization in five or six years. In theory, this will repeat every five or six years, possibly reaching an opportunity for an IPO somewhere along the line. So our deal has turned out to be good even for the younger doctors.”

13 Will this undercut our ability to recruit doctors in the future?

“Younger doctors who are looking for a career and considering joining a practice that’s owned by a private equity company will realize that some of their potential earnings have already been pledged to the private equity firm and taken off the table,” notes Mr. Pinto. “That’s a problem because it’s getting harder and harder to recruit doctors. We have fewer residency slots, and more older doctors are retiring, so the demand is going up. That trend is blotting up all of the available doctors, and base salaries for new doctors are going to continue to rise materially in the years ahead. As a result, the private equity companies will find it more and more difficult to hire young doctors as the senior doctors retire. I think it’s a ticking time bomb for many of these companies.”

Mr. Pinto acknowledges that some of this might be offset in certain situations. “If an organization has become very large-scale, with revenue over $100 million, and it’s located in a desirable market that’s attractive to younger doctors, it may work out fine,” he says. “A group in that situation will have the scale

|

to allow more efficiency with operations, and will be able to be effective when negotiating managed-care contracts. But many others won’t have the scale to be able to overcome these difficulties. And they may not be located in parts of the country that are easy to recruit to. So the reduced salaries they’ll have to offer to young doctors won’t be sufficient to attract the doctors they need.”

Dr. Lindstrom says that so far, his group hasn’t had any trouble hiring new young doctors, despite the new arrangement. “Our goal is to recruit the best and brightest, and so far we haven’t seen a problem there,” he says. “The package we offer is still competitive, both in salary and in terms of opportunity to earn equity. For example, we recently hired a glaucoma/cataract surgeon, and those are among the most highly in-demand ophthalmologists today. That individual had many other offers but still chose to join us. At the same time, I would say that our buy-in, because our practice is pretty valuable, was intimidating to a lot of young doctors. Given the uncertainties that exist about the future, some would take a look and say, ‘You’re asking me to pay something that has a lot of zeroes behind it to be an equal partner in your practice. I’m already in debt, and that’s scary.’ So I think the reaction new young doctors will have to joining us will depend on the individual. Hopefully, the fact that we can offer an equity opportunity will make a difference.”

Dr. Katzen says that because of the way his deal is structured, it hasn’t undercut the group’s ability to hire new doctors. “If you’re not an owner, you’re paid a percentage of your production,” he says. “Nobody’s lowered that percentage.”

14 How is this trend likely to work out in the long run?

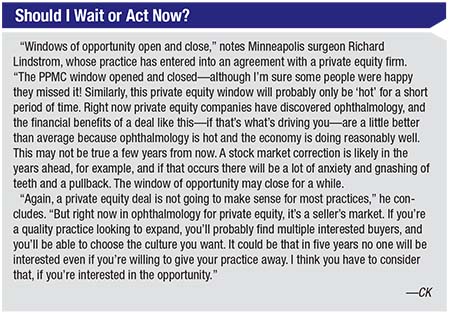

Mr. Pinto sees the current wave of private equity purchases as a limited phenomenon, rather than something that will become a huge, sweeping trend. “We’re certainly not going to end up in a world in which 90 percent of practices are owned by private equity companies,” he says. “But we are moving inexorably toward more consolidation, whether it’s in the form of private equity, or hospitals buying practices, or large practices buying smaller practices. This era of increased consolidation will probably continue for some years.

“What we’re seeing right now is a series of private equity transactions that are allowed to happen because of broad financial conditions, taxation policy, and other current factors,” he continues. “I would forecast on the negative side for most of these transactions because for most of them, the underlying enterprise model is flawed. I’ve spoken to about half of the private equity companies, and a significant percentage of them are going down the same rabbit hole that we did in the 1990s. Yes, there are a few thoughtful folks doing this now that will probably survive. Some will evolve their transaction model and the way their business works, and they’ll do well. But I think in two or three years people will look back at this as a bubble.”

If the bubble

|

collapses, will it happen the way it happened 20 years ago? “I think things will unwind a little faster this time, because back then the companies were public companies,” Mr. Pinto says. “Public companies have better access to capital. Back then we were able to keep the party going because someone kept bringing more rum and putting it in the punch.”

What if the model fails five or six years from now? “I don’t believe it’s going to fail, but in the current world, anything is possible,” Dr. Lindstrom acknowledges. “Of course, there’s some question about what a second transaction will be like, but we’ve already seen one private equity com-

pany sell to a second investor; that was Varsity, and that went well. We’ve also seen several private equity transactions in dermatology and other fields, and we’ve seen a few of the very mature groups go public. So, at this point we haven’t seen any failures or crashes like those we saw with the PPMCs. Of course, it’s perfectly reasonable to be concerned that this could end badly, but so far, so good.”

15 How can we maximize the chance of a good outcome?

If you’ve decided that pursuing a private equity partnership could work for you and your practice, these strategies will help ensure a positive result:

• Don’t pursue this unless your goal is to grow. “Just as with a growth stock, the private equity company fertilizes the practice with capital, both human and financial, and good business judgment, helping to enhance practice growth,” says Dr. Lindstrom. “For that reason, the right practices [for this type of partnership] are those that have the opportunity to grow, and equally important, want to grow. At the very least, you need to have a goal, a reason to pursue this option, a business plan. You shouldn’t pursue this just because somebody calls and waves a big number in front of your eyes. If you have a clear goal, then you can decide whether or not a private equity partner will enhance or detract from your chances of achieving that goal.”

• Be willing to share control of your practice. “If an individual is a solo practitioner who is fiercely independent and cannot or simply doesn’t want to work with a partner, private equity may not make sense,” Dr. Lindstrom says. “Mavericks who want to run things their own way probably wouldn’t be happy having others involved in decisions. At the same time, a private equity group probably wouldn’t want that individual either, so it will end up being a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

• Surround yourself with advisors you know and trust. Bruce Maller, founder, president and chief executive officer of The BSM Consulting Group, says that a key to ending up with a good deal is to understand your limitations. “Don’t let your ego guide your assessment and decision-making,” he says. “Instead, surround yourself with people you know and trust—including legal, accounting and business consulting people. Those individuals can help you clarify your vision and build consensus among the partners about what’s the best course of action. Perhaps most important, they can help educate you. I spend a lot of time educating clients about the positives and negatives, helping to guide them to a good business decision. If it’s a decision to go ahead, I guide them on retaining good legal counsel and tax counsel, because these transactions are very complicated. It’s important to make sure you won’t be looking back and wondering, ‘Why did we do that?’ ”

• When negotiating a deal, keep the long term in mind. “You have to be smart about how you construct these arrangements so that they’re likely to be sustainable for the next 10 to 20 years,” says Mr. Maller. “That’s not necessarily how a private equity firm thinks. They think about creating value in the next three to five to seven years and then selling that interest, to make sure that they satisfy their obligations to their private equity investors.”

• Make your decisions for the right reasons. “The worst possible reason to go down this path is because someone you know did it and got a big payoff,” notes Mr. Maller. “Even with a big paycheck you can end up very unhappy. If money is the only thing you’re thinking about, your decisions are not likely to produce ideal results.”

• Consider how the deal is going to impact younger employee physicians in your practice. “Your younger employees may be at the greatest risk,” Mr. Maller points out. “They may not have been involved in the original transaction, and they’re most likely to suffer if the next investor, a few years down the line, isn’t as friendly or as concerned about how a deal affects them as the first investor hopefully was.”

• Be aware that a big payoff can alter a doctor’s level of motivation. “Key doctors in the practice may become less motivated as a result of the financial change,” says Mr. Maller. “Once physicians have sold the practice and put money in the bank, some may lose their interest and passion, realizing they don’t need to work so hard to ensure their financial future. In fact, some may not even be motivated to stay. After a while some may say, ‘This isn’t very much fun anymore, I’m just coming to work and collecting a paycheck. I got all that money up front; maybe I should terminate. I’ve signed a noncompete, so maybe I’ll take a couple of years off. Maybe later I’ll come back and start over again!’ Of course, their interest and passion is what made the practice great in the first place, so this is not a good thing for the practice.”

Mr. Pinto says that one of the biggest unforeseen problems that occurred back in the 90s was the reaction of many doctors to the influx of cash. “Each of these doctors had a pretty good-sized check coming in at the front end for the purchase,” he notes. “Some of what they received was stock, but some was cash. That caused a lot of them to back off their productivity. A lot of doctors said, ‘Now that I’m over my financial retirement finish line, I don’t need to work so intensely.’

“Unfortunately, if a doctor cuts his patient volume by just 10 percent, the profits of the practice can do down as much as 20 percent,” he says. “That’s a risk the private equity companies are taking, and I’m sure that they’re going to be experiencing that as well.”

• See if the deal passes the two-part “acid test.” Mr. Pinto says his advice to a physician considering this type of a deal is to use a simple two-part “acid test.” “A deal like this can be an absolutely fantastic thing to do, and very appropriate as a business and professional next step, under two conditions: The first is that the money you receive up front in the transaction is enough to take you comfortably over your personal financial finish line,” he says. “I’m not talking about something that can be clawed back later on, but the irrevocable payment you receive at the front end when the ink is drying.

“The second condition is that you’re not emotionally attached to what happens to the practice next,” he continues. “Some doctors would be carried over their financial finish line by such a deal, but they’d be anguished if their practice was run into the ground, or if key policies were changed, or key staff members were dismissed. Such a doctor should not sell to a private equity firm.”

For Better or Worse

In the final analysis, is this trend going to be a good thing for the field of ophthalmology?

“I’m torn about what I’m seeing,” says Mr. Pinto. “I see many of these companies heading in the wrong direction. It’s too early to observe the consequences, but I think in a few years we’ll see a significant number of practices partnered with private equity firms that will be unhappy with the level of administrative support they get, or the limitations that they’ll find themselves dealing with, financially and operationally.”

Mr. Maller says he’s not “for” or “against” this trend. “I think a private equity investor can bring a tremendous amount of value to a practice in the right situation,” he says. “The right situation is where you have the right type of practice, and everybody goes in with their eyes wide open, and no one loses sight of what it takes to build a great business over the next 25 years.”

Dr. Katzen notes that there are plenty of naysayers when it comes to the private equity phenomenon. “They can come up with plenty of reasons to be negative,” he notes. “But the reality is, this can work. I’m proof of that, because I’ve already succeeded.” REVIEW