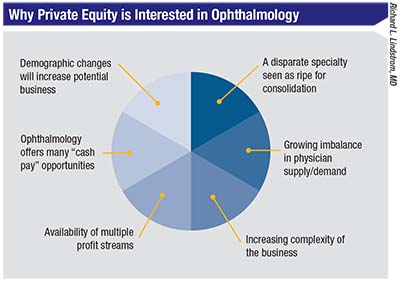

One of the most interesting things occurring in the field of ophthalmology today is the phenomenon of private equity firms buying ophthalmology practices. These partnerships have huge financial ramifications, as well as the potential to impact the health-care system and patient care.

The basic premise is that a private equity firm offers to form a partnership with an ophthalmology practice that it believes has the potential to grow. It provides funding to the practice owners, including an upfront payment in cash and/or stock, in exchange for a percentage of future profits. Ultimately, the goal is to increase the value of the practice by investing in its growth—often partly by consolidating it with other practices—so that in a few years it can be resold to another private equity firm for a significant profit.

|

| One obvious advantage of selling a practice to private equity is an influx of capital. Katzen Eye Group’s multiple private equity transactions have enabled extensive renovations of the physical plant. Left: The new aesthetic surgery waiting area. Right: A redesigned front desk area greets patients. Other changes have included new exam rooms, an expanded room for diagnostic retinal testing, a large pediatric section with waiting area and exam rooms (formerly a call center for the practice) and an upscale concierge area for cataract patients. |

“Private equity’s interest in the specialty of ophthalmology started three or four years ago when private equity firm Varsity Partners did a transaction with the Katzen Eye Group,” says Bruce Maller, founder, president and chief executive officer of The BSM Consulting Group. “A few smaller deals had been done previously, but that was the first significant deal in ophthalmology. Before you knew it, many of these firms—as well as some investment banking firms—were cold-calling doctors. Our firm started getting calls from many of our clients asking what we thought about this, and in some cases we were contacted by the private equity firms, who wanted to know more about the field. In the meantime, transactions began to happen. Today, I believe nearly 20 private equity transactions have occurred, although I’m not keeping careful track.”

The widespread nature of this phenomenon has been confirmed at recent ophthalmology meetings. Richard

L. Lindstrom, MD, an attending surgeon at the Phillips Eye Institute and Minnesota Eye Laser and Surgery Center in Minneapolis and managing partner at Minnesota Eye Consultants—now part of Unifeye Vision Partners, as a result of partnering with a private equity firm—spoke at this year’s Hawaiian Eye meeting. He reports that a survey of the audience indicated that about 35 percent of the audience had received a call from a private equity company. “About a third of the audience was currently interested in the model,” he adds, “and about 60 percent said they might consider it at some time in the next five years.”

In this article, part one of a two-part series on private equity and ophthalmology, several of the crucial questions doctors are currently asking about this phenomenon are answered by those who are actively involved in these deals.

1 Why is this happening now? “Right now private equity is very well capitalized,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “The high-quality private equity groups are not just opportunists; they have a business plan and they’re looking for specific criteria in a practice. They’ve done well by operating and expanding businesses in several other fields, especially dermatology, which is a little bit like ophthalmology. In particular, they’re looking for specialties that are not hospital-based, and ophthalmology practices are perfect. We’re out in the community with our ambulatory surgery centers and our own offices, much like dermatology or plastic surgery or dentistry.”

John Pinto, president of J. Pinto & Associates, an ophthalmic practice management consulting firm, notes a number of factors that are stimulating the current wave of private equity offers. “For one thing, we have a bolus of doctors, baby boomers in their late 50s and 60s approaching retirement,” he points out. “Those doctors are most likely to benefit from a private equity deal, and they probably have the power to make it happen, even if younger doctors in the practice are less certain about going down this path. A second factor is that tax regulations are very favorable for the private equity companies and their investors right now. Third, capital has been very readily available—at least until recently, now that capital markets are beginning to tighten again. We’re very late in the post-2008 Great Recession business cycle. We’re still cooking along if you read the stock pages, but the expansion is getting pretty long in the tooth. The Fed is now tightening interest rates, so it’s going to be harder to get access to cheap capital. That will not work in favor of the private equity companies.”

2 How does this trend compare to the PPMC wave 20 years ago?

Mr. Pinto’s experience with similar financial constructs 20 years ago has left him with some serious concerns about the current wave of private equity groups purchasing ophthalmology practices. “I know that for a certain class of surgeon—older surgeons or surgeons who are in over their heads operationally or financially, divesting to a private equity company could be a great thing to do,” he says. “However, in this current trend I see elements of the errors many companies made back in the 1990s with the so-called ‘physician practice management companies,’ or PPMCs. Most of those were aggregates of private, independent practices, combined into large, publicly held companies like the one I was involved with—Physicians Resource Group.

“The history of that wave of commercial experiments was pretty dreadful,” he continues. “A lot of very

|

entrepreneurial doctors were involved. We all thought we were really bright, but we had our heads handed to us. Virtually all of the firms that were developed went away. Along the way a lot of doctors were financially harmed, and even those who weren’t financially harmed had to undergo a lot of frustration.”

Are there differences this time around? “These are private, not public companies,” Mr. Pinto points out. “That changes the source of the funding and the nature of the risk. Nevertheless, the transaction model today has a lot in common with the previous PPMS model. There’s an agreed-upon amount of earnings that the acquired practice is expected to throw off, which will typically reduce the incomes of the doctors in the practice.”

Dr. Lindstrom notes another difference as well. “With private equity you’re not just selling a little bit of your revenue, you’re actually selling your practice into a ‘mutual fund’ of practices,” he says. “The last time, the doctors could hold the PPMCs hostage; in this case, it’s the other way around. If the doctor becomes really unhappy, he or she will be the one that leaves, not the company.”

3 What does a practice stand to gain by partnering with a private equity firm?

Two doctors with successful private equity partnerships say there have been multiple benefits for the doctors and practices:

• Monetizing practice value. “Minnesota Eye Consultants is now 29 years old, with 11 partners,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “Generally when you sell that value to a younger associate, you do so at a relatively discounted value. Private equity, on the other hand, is willing to pay full value—or even a premium—for a high-quality practice. So our partnership was an opportunity to convert equity in Minnesota Eye Consultants into cash, along with obtaining some equity in the larger group, Unifeye Vision Partners, if we wished.

“As it turned out, all 10 of our partners wanted to invest forward, because in five or six years, once we and the four other markets are built up to around the $500 million top-line revenue level, there will probably be a recapitalization,” he continues. “Another private equity company will come in and acquire Unifeye Vision Partners—hopefully at a premium. Then, as time goes by, it will become a $1- to $3-billion top-line-revenue eye care delivery system. Ultimately, it could become a public company.”

• Funding infrastructure growth. Brett W. Katzen, MD, FACS, president of Katzen Eye Group, based in Baltimore, has been part of two successful private equity ventures: first with Varsity Healthcare Partners (considered the first major ophthalmology-private equity partnership in the current wave) and later, Harvest Partners. Dr. Katzen says Varsity invested a lot of money into his practice infrastructure. “They invested significantly into my ambulatory surgery center, created a larger oculoplastics area and a larger pediatrics center, and built a first-class concierge center for refractive cataract surgery,” he says. “They shut down one of my offices and replaced it with a new office almost three times as big, with more equipment and more lanes. They enlarged my preoperative and postoperative areas, and they moved the nurses and administrators into a less-posh space so the first space could be used for clinical work. They got me a brand new femto laser, replacing the one I already had, and they moved my femto out of the OR into another room so we could have four ORs and a separate laser room. They also bought us a bunch of new microscopes.”

• Relieving doctors’ personal debt load. Dr. Lindstrom says that funding from the private equity company relieved the doctors of personal debt that had accrued from financing capital improvements themselves. “We were growing at a rate of about 8 percent per year, but we were capitalizing that growth with personally guaranteed bank debt,” he says. “We were getting ready to build a major office in St. Paul—about a $6 million investment—and some of my partners were becoming uncomfortable with the amount of debt they were guaranteeing. We knew this partnership would relieve us of that debt load.”

Dr. Katzen concurs that after you’ve borrowed a lot of money to invest in your practice, it can become a burden. “I was far enough in debt to the bank that I couldn’t borrow more money to build a new office or concierge center,” he says. “I couldn’t afford to move my LenSx laser out of the room it was in. I’d been funding everything myself, to the point where if I spent 10 grand or more, I had to tell the bank. It was cumbersome, smothering. Now, that’s not an issue. I’m out of debt and the private equity company is happy to invest in things they believe will make the business more profitable.”

• Helping to broker consolidation and enlargement to remain—or be-

come—a force in the marketplace. Dr. Lindstrom says this was a way to fund their business plan to grow significantly over the next 10 years. “In the future I see situations in which small practices may be left out of large insurance panels,” he says. “That’s starting to happen in some states. In our market we want to be ‘too big to ignore.’ We want to be the practice that everyone bills around, if you will, as a third-party payer. There’s no way to ignore Twin City Orthopedics, because they have 60 percent of the orthopedic surgeons in the Twin Cities, and they have an office in every nook and cranny. We hope there will also be no way to ignore us, although our critical mass will be much smaller. Currently we represent about 10 to 15 percent of the eye-care marketplace in the Twin Cities. We hope to end up being 25 percent, which we believe will make us impossible for insurance companies to ignore.”

Dr. Katzen agrees that this kind of deal can help a practice survive in the current environment. “We have to compete against the hospitals and the insurance companies and the Kaiser Permanentes,” he says. “They have an advantage because of their size. This option gives us an avenue to consolidate and scale and still provide great eye care.”

• Allowing more equity incentivization. Dr. Lindstrom notes that the new group doesn’t have some of the legal limitations associated with a professional corporation. “In Minnesota Eye Consultants we had no way to allow a senior administrator such as a president or COO to own equity in the practice,” he points out. “However, they can own equity in Unifeye Vision Partners. So we can now equity-integrate, including our senior management team, giving them equity incentive.”

• Making difficult decisions a doctor would prefer to avoid. Despite his fondness for the business part of this, Dr. Katzen points out that doctors often have the wrong personality to make difficult business decisions. “We want to be nice to everybody and do what feels good,” he says. “In business, you have to make decisions that don’t always feel good. The private equity people make those decisions for you.”

4 How much risk are we taking?

Mr. Pinto notes that much of the risk in the current situation falls on the private equity companies. “They’re taking considerable risk,” he says. “For the doctors in the practice, the biggest risk falls on the younger doctors who could find themselves locked into a relationship with the owner of the practice and taking a pay cut for many, many years. Of course, you’re not a slave. If it doesn’t go well, once your contract is up you can leave.”

“Back in the ‘90s, if you owned stock in a PPMC and you never sold it and the PPMC failed, you basically ended up getting nothing,” Dr. Lindstrom points out. “That was the case for a lot of doctors. But in this model, it won’t be the doctors who suffer. If the private-equity-based group fails, we’ll end up buying our practice back at a discount, as we did when the PPMCs failed—but this time the doctors will have cash in the bank.”

Dr. Lindstrom notes that future disruptions in America’s health-care system or the economy in general are possible, if not likely. “I think the biggest disruptions that might happen would be going into a major recession, or the legislature saying we can’t afford health care and voting in a single-payer system,” he says. “They could decree that no doctor can own an ambulatory surgery center or an optical shop; they could say, ‘We’re going to pay every doctor a salary, and all a doctor can do is see patients.’ If you don’t think that could happen, I don’t think you’re looking carefully at what’s going on in Washington.

“The question is, who would get hurt if that happened?” he continues. “The private equity company, not the doctor. All of a sudden, the holdings of that company that have been underwritten by the endowments of major institutions and wealthy individuals would decline in value. The doctor who did the private equity deal would be buffered to some extent, with money in the bank and no debt. The private equity company would have to sell off some assets, probably at a loss. The doctor just has to say, ‘OK, I used to make $300,000 a year, now I make $150,000, so I’ll have to adjust my lifestyle.’

“The bottom line is that although doctors tend to think they’re taking all of the risk, there’s risk on the other side, too,” he says. “In fact, having a well-capitalized partner may help mitigate some of that risk as we go through future bumps in the road—which, in my opinion, are definitely coming.”

5 How much control are we giving up?

Dr. Lindstrom acknowledges that doing an equity deal does involve giving up some amount of practice control. “We don’t get to decide everything by ourselves anymore,” he says. “Now we have an additional person at the table. That additional person’s primary control is over the checkbook, making decisions involving capital investment such as building a new ambulatory surgery center or opening another office. They also have the deciding vote on when we’re going to add another practice to our mutual fund of practices and how they’re going to compensate that practice to join the group. However, I think that could be a good thing, because these are smart businesspeople.

“When I was in solo practice, I pretty much decided everything,” he notes. “Then, as I added partners, I had to share decision-making with them. I now have 10 partners, and I don’t get to decide things just because I’m the senior doctor. So before the equity transaction took place, we were already a democracy with 11 votes. By selling to a private equity company we did give up some control—but everybody in a group practice has already lost control.”

6 Which practices are good candidates for a private equity partnership?

One thing everyone agrees on: Partnering with a private equity company is not a good idea for every practice. So, what makes a practice a good candidate?

Mr. Maller says that when doctors call and say they’re considering doing a deal, his first question is: Why? “Why would you want to do this?” he asks. “What are your objectives? What are you trying to achieve that you think this might help you with? Typically, the doctors are intrigued by the possibility of monetizing some of the equity in their practice. They like the idea of having a strong, disciplined financial partner who will help them build infrastructure and grow the practice to be more competitive and efficient. But usually the overarching consideration is, ‘Oh my goodness, somebody is willing to pay me a lot more money for my practice than I could ever have gotten from a younger associate or a hospital.’ Clearly, the financial part of the offer stimulates a lot of interest.

|

“My advice always starts with this: As a practice and/or surgical facility, you need to be clear about your long-term vision for your practice,” Mr. Maller continues. “You have to ask yourself if having a financial partner is going to help you to attain near-term and longer-term objectives. Because if you don’t have a vision that involves building something substantial, then you and private equity are not likely to be a good match.”

Mr. Maller explains that private equity firms take money into their investment funds from a variety of high-net-worth individuals and institutions. “Private equity is normally a small slice of an investor’s portfolio,” he says. “However, it’s considered the highest-risk type of investment. For that reason it demands the highest return, and the only way an investor is going to get a high rate of return from investing in your practice is if you have a significant trajectory to grow cash flow. A business or practice that’s not motivated to build or grow is not a good platform target for private equity.

|

“The exception would be that your practice might be a good ‘fold-in’ acquisition,” he notes. “You might want to make a deal because you’re in the latter part of your career, and you’ve done fine but you don’t want to sell your practice to young associates. In that situation it doesn’t really matter that you don’t have a great plan to build and grow, because you’re planning to retire. The private equity-backed investor will put young physicians into your spot—presumably for a lower cost of labor, producing more cash flow as a result. At least, that’s the theory.”

“A private equity deal might make sense for 10 to 30 percent of U.S. practices, but it won’t make sense for the rest,” says Dr. Lindstrom. “In actuality, only a very select group of practices will even have the opportunity to do a deal of this kind. If you receive an offer to buy your practice for a lot of money, you may do your due diligence and decide it’s not a good deal. Or, you might want to do a private equity deal and not be able to find a buyer.”

Mr. Maller adds that overall, he’s advised the majority of his clients not to proceed with a private equity partnership.

7 What about the second transaction—the one you can’t control?

Dr. Lindstrom understands that doctors considering partnering with a private equity company may be concerned about what will happen down the road when and if a second buyer takes over. “The doctors get to negotiate the deal with the first partner,” he notes. “They know who the people across the table are, they know their culture, they can look them in the eye, check their history, and so forth. But there’s no way to know who the buyer will be if a second or third transaction takes place in a few years. I’m sure people worry that the group might be sold to the devil. The new owners could come in and fire employees, or tell the doctors they have to work 80 hours a week.

“However, I think that’s unlikely,” he says. “Look at similar transactions in the corporate world when mergers and acquisitions occur. You don’t usually see extremely onerous working conditions coming in. Yes, you might see some adjustments made, but usually an acquiring company’s primary goal is to retain the value of the assets they acquire and add additional capital to grow it again so they can re-sell it.”

Dr. Katzen has already experienced a second transaction; he describes what happened. “My first private equity partner invested a lot of money into my platform,” he says. “Together, we formed a management team of executives that ran the company and took it to the next level. Once it became really successful, my private equity partner said, ‘Brett, I’m out. We’re selling.’ The people at Harvest said, ‘We really like your management team and structure. We want to buy that from you.’

“When Varsity sold to Harvest our contract didn’t change,” he continues. “They bought the company ‘as-is.’ So for the doctors it was pretty much a seamless transition. At the same time, our doctors were happy because they realized a bump in the value of their stock. Most of them just rolled it into the next company, because things have been going so well. In fact, many other doctors in the practice who were nervous about taking stock when the first sale happened decided to jump in on the second hit. Now everybody’s pushing everyone to work hard and make this an even bigger success, hopefully leading to another financial payoff.”

Dr. Katzen says that when Harvest took over, the first thing they did was hire even more best-in-class leadership. “They brought in C-suite executives who’d run big companies and built big businesses,” he says. “Now my compliance officer is a health-care attorney. My CFO is also an attorney, and he’s run big businesses. My COO was the chief executive at another large business. Harvest created revenue-cycle management teams in each region, so they can take care of this on a local basis.

|

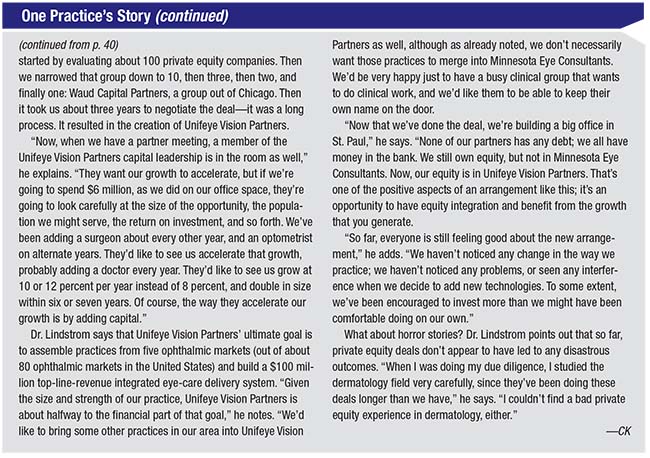

| Richard Lindstrom, MD, notes that working out a private equity deal involves an evaluation phase; time spent negotiating business terms; and then a closing process. In his case, the practice began considering a deal 18 months before engaging with the company. Once a potential partner was chosen, the deal still took months to complete, as shown above. The first due-diligence process led to the creation of contracts at two months; then another two-month period was spent doing further due diligence on the contracts themselves. At six months, the deal was finally closed. |

Marketing, human resources, compliance, benefits, IT and physician recruiting are all handled centrally. Harvest also revamped my infrastructure, with better revenue-cycle management, computers, next-generation EMR systems, you name it. They put a ton of money into IT, and they centralized all of our phones into one phone-answering center for the whole area.”

Dr. Katzen acknowledges that worrying about the nature of a second purchase is reasonable. “However, we didn’t have a bad experience,” he says. “We were bought by people who understand that the doctors are the life-blood of the organization. They understand that if you don’t have happy and healthy doctors doing their job, the business goes sour. As a result, they’re not changing the nature of our job, just trying to make it even more efficient. Meanwhile, we’ve moved from being part of a $200-million fund to being part of a $2.3-billion fund.”

8 Will the private equity company base its decisions on money alone?

Obviously, money is the prime motivation when a private equity company purchases a practice, so it’s not unreasonable to worry that decisions might be made that will undermine the practice (or its patients) simply because those decisions might improve the balance sheet for the next buyer. Along those lines, Mr. Pinto repeats a story he often tells when giving presentations on this topic. “Back in the ‘90s, I was sitting with a venture-capital guy putting a deal together,” Mr. Pinto recalls. “I remarked that I was happy to be a part of this because I’d always worked to help make practices work better. He leaned over the table and said, ‘I’m not sure you understand our business model. We’re not going to make these practices better; we’re not going to manage them, even though we’re called a practice management company. We’re going to go public, sell our stock and then move on to our next deal.’ Of course, that was 20 years ago, but to a large extent that’s also where we are now.”

One way in which such an attitude might manifest would be having the new partner come in and start eliminating resources in a quest to improve profitability. Clearly, many people in other industries have experienced the phenomenon of private equity companies firing employees and closing lines of business to make the books look better for the next potential buyer. However, Mr. Pinto says he doesn’t think that’s likely to happen with an ophthalmology practice. “In most practices in operation right now, you wouldn’t increase profit much by reducing costs, because most costs involved in running a practice are fixed,” he points out. “The best way to increase profit in an ophthalmology practice is to enhance revenue. For example, in a typical practice, if the doctor sees just three more patients per day, that generates $100,000 more per year in profit. So I don’t think you’re going to see a lot of cost-cutting measures taken. Anybody who is thoughtful is going to be working on revenue enhancement; adding surgery centers where they don’t already exist, adding an optical where it doesn’t already exist, and so forth.”

“Of course private equity companies care about the money, but they’re also about the business being successful,” notes Dr. Katzen. “They’ll never be able to sell to another partner unless they build a great business.”

9 Will the private equity company help manage the practice? If so, how?

Mr. Pinto says that a big part of the problem during the PPMC wave 20 years ago was that doctors expected the PPMCs to help manage their practices. “After all, the name of that phenomenon implied that these were practice-management companies,” he points out. “I suspect that a lot of practitioners who are being courted by private equity companies now are laboring under the same expectations. They think, ‘My practice is getting harder to manage, it’s outside of my comfort zone, so I think I’ll join a private equity company. That firm will help me manage my practice better.’

“The reality is, many of these companies are not in the business of improving practice management,” he says. “Their purpose is to aggregate earnings from the practices they pull together, with the aim of generating a subsequent transaction a few years from now in which they’ll take that aggregated value and sell it to an even larger consolidator. It’s about making a profit for their investors, not helping doctors manage their practices. What I’ve seen so far is that most of these companies are in a ‘land rush’ right now, anxious to write deals.

“Imagine that you’re an executive in a private equity company,” he continues. “You have a certain amount of capital and a limited amount of time to get these deals done. Would you put all of those resources into sending your people out, negotiating, doing analysis and closing deals, or would you take some of your resources and deploy them improving, managing, fine-tuning and enhancing the practices that you already added to your quiver? You’d probably put everything into acquisition.

“During negotiations, when a private equity company is discussing the transaction and listing the benefits for the selling doctor, the promise of better management and taking all of these nonmedical chores off your hands is prominent,” Mr. Pinto notes. “But when I talk to the folks on the private equity side of the world, most of them don’t appear to be very interested in making practices better. Think about this: The bonuses received by young private equity executives are going to be based on how many deals they did, how big an earning stream they’ve brought into the company. They’re not going to be rewarded by whether this or that practice is running more smoothly.”

On the other hand, Dr. Katzen points out that a private equity company can’t just make a purchase of this kind and then remain ‘hands-off.’ “When you buy practices, you have to integrate them successfully,” he says. “You can’t just say, ‘OK, doctors, mail us our portion of the check.’ That wouldn’t work, because a practice would probably spend as much as they could, especially knowing that someone else is going to take whatever profit is left over. To make this work, the private equity people really have to manage and integrate these practices skillfully.”

Mr. Maller says that in his experience, private equity companies influence how a practice is being run indirectly. “What the private equity investor brings is business knowledge, experience and discipline—primarily financial discipline,” he says. “They’re not going to run your practice, but they know how to find talent. So, they’ll help you identify gaps in your talent pool and assist you with recruitment to make sure you bring in the right people to help you achieve your objectives. They’ll also help with infrastructure to ensure that your business gets stronger over time. Ideally, they’ll be guiding you, coaching you, supporting your team and being good partners with your management team.

“In order to do this, when these firms come in and make an investment, they create a governing board,” he continues. “The governing board is often composed of two or three physicians and two or three members of the firm. Sometimes they’ll also bring in independent experts or consultants for an outside perspective. The operating team reports to the governing committee, so the governing board is influencing the management of the company, but they’re not the ones doing the work.”

Mr. Pinto adds that some private equity companies will have an unpleasant wake-up call if they do try to manage ophthalmology practices. “Ophthalmology practices are materially more complex that what people encounter in other business circles,” he says. “I know of a $50-million practice that was not able to find a CEO in the health-care field, so the doctors decided to hire a fellow who had previously been the number-two person in command of a worldwide engineering firm—a $2-billion company employing something like 8,000 engineering professionals. I got a call from him six months into the new job. He said that running the $50-million practice was much more complex than running the $2-billion company. He was thinking about throwing in the towel! So companies who think that stepping in to manage a large ophthalmology practice will be straightforward may be in for a shock.”

10 How do you find a good partner?

Obviously, as in marriage, choosing the right partner is the most important part of the deal.

• Take your time and research potential companies thoroughly before making a decision. “I’ve met and talked to 15 or 18 of the private equity firms,” says Mr. Maller. “Out of all of those, I’ve encountered three or four that clearly set themselves apart. How? It’s the people; their attention to detail; their sensitivity; their awareness and understanding of our business; and their willingness to support doing the right thing for patients, staff and doctors. Those are the firms that I think will be very successful with this model.”

Dr. Katzen says that it’s important to not be in a hurry. “I spent at least five years doing my homework before I pulled the final trigger,” he notes.

“There are some private equity companies where the first thing they do is fire the current leadership and take over,” Dr. Lindstrom says. “We wanted a partner that wasn’t going to do that, and in our first transaction we achieved that goal. The partner we chose wasn’t intending to increase earnings by reducing overhead; their priority was to grow the practice at an accelerated pace. I think you can probably delineate that with your first partner pretty easily, but you still have to do your homework and choose your partner wisely.”

Dr. Lindstrom adds that if you’re not the first group to join the ‘mutual fund’ of practices, it’s important to look at who the other partners are. “If the practices already involved don’t seem like a good selection—or if they’re practices you wouldn’t want to partner with—then that group is not going to be a good choice for you,” he notes.

• Consider the motivation of the company you’re partnering with. “The investor’s motivation isn’t necessarily aligned with the motivation of the doctors,” says Mr. Maller. “The thing that makes a practice successful is usually an entrepreneurial, passionate physician or group of physicians who want to create a great business, a great brand, and provide great patient care. You run the risk of losing that when financial people come in. They might say, ‘You guys were willing to keep all these people on, but we’re not hitting our targets, so we’re going to let 30 percent of the staff go.’ ”

Mr. Maller says in his experience, however, many private equity companies do understand that if you don’t treat the practice well, you won’t make money. “The private equity firms that I recommend to my clients are run by honest and decent individuals,” he says. “They understand that if you don’t operate this the right way, if you don’t take care of the doctors and the management, the model may break down. Making money and providing great patient care are not mutually exclusive.”

Mr. Maller adds that it would be naïve to think that a practice owner isn’t also at least partly motivated by making money. “That doesn’t prevent a doctor from delivering extraordinary care and great service,” he points out. “And, a good private equity firm can play a very important role in helping to build and grow a great enterprise.”

• Be prepared for potential deals to falter. Dr. Katzen says he met with 15 different private equity companies when researching the first deal. “I negotiated a deal with another group that I liked,” he says. “They were going to be a minority owner, and I was going to sign that deal because I loved the group, and they were going to let me and my team run the business. But at the eleventh hour, it turned out that their stock would be ‘A’ class, whereas mine would be ‘B’ class. That meant that even though I was majority owner, they’d still have all the control. That wasn’t going to work for me.”

11 What will happen to the practice if the deal works out badly?

“In some cases, that would be resolved in the courts,” says Mr. Pinto. “In some cases, the bond holders will take a haircut. In some cases, the doctors will end up buying their assets back for cents on the dollar. Back in the ‘90s, a lot of doctors ended up buying their practices back from the PPMCs. Some of them made out very well, but they went through a lot of pain and suffering. And obviously, this would be very problematic for a doctor near retirement. If you’re planning to retire in five years and something happens to your private equity company at the two-year mark, having to buy the practice back—even at a discount—will put a lot of wobble into your last few years of practice.

“That’s why you want to use the ‘acid test’ before taking the plunge,” he says. “First, make sure the irrevocable monies that you get at the front end take you over your financial finish line. Second, make sure you don’t have any emotional investment in what happens afterwards. If you follow that strategy, you’re now financially and emotionally independent. If the private equity company blows up, you just haul up the truck, and you’re done. This happens in the rest of the business world all the time. It’s an abrupt, shocking denouement compared to the genteel worlds most of us live and work in.” REVIEW

Next month, experts address questions such as the impact of the deal on patient care as well as the effect of lower salaries on an ophthalmic practice.