Scleral Bi-Capsulotomy Capture

Dr. Arbisser, an adjunct associate professor at the University of Utah’s Moran Eye Center, calls her approach scleral bi-capsulotomy capture, and though it involves maneuvers that may take some getting used to, she thinks surgeons would benefit from SBCC in the long run.

After studying the unique techniques of Canadian surgeon Howard Gimbel, MD, Austria’s Rupert Menapace, MD, and France’s Marie Tassignon, MD, Dr. Arbisser says she was struck with an idea. “It occurred to me that all bag/lens subluxations have one thing in common: a capsulorhexis,” she says. “We never saw bag/lens subluxations in the days of the can-opener capsulotomy, and you very rarely see a pseudoexfoliation patient subluxate his normal crystalline lens. I then reasoned that if I could stent the anterior capsule by capturing the optic in there, and place the haptics in the sulcus—which is partially defined by the zonules—there would be no movement, pressure or weight on the bag. So, in a sense, the bag would support the lens and the lens would support the bag, with the most important part being that the lens is captured to prevent phymosis. It occurred to me: Why not combine these two techniques into one routine procedure? In the procedure, scleral bi-capsulotomy capture, you’ve got a three-piece lens placed in the sulcus and captured through both the anterior and posterior capsules.”

Possible Advantages

Dr. Arbisser says eliminating posterior capsule problems is a big reason to perform SBCC.

“The advantage of mastering and not being afraid of the posterior capsule is huge,” she says. “We know from Dr. Menapace and his extensive studies of fellow eyes that the anterior hyaloid is really the barrier between the front and the back of the eye. The posterior capsule is redundant. Because of Wieger’s ligament and the anterior hyaloid, if you leave

|

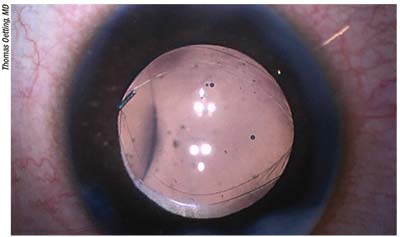

| Scleral bi-capsulotomy capture consists of capturing the optic with both anterior and posterior capsulotomies and placing the haptics in the sulcus. It could potentially eliminate the incidence of posterior capsular opacification, but it comes with a learning curve. |

Dr. Arbisser says there’s a second, more-immediate reason to pursue this technique. “Those cases with posterior plaques will get an immediate visual rehabilitation,” she avers. “So, too, will posterior polar cataract cases in which there’s a very weak and very unreliable posterior capsule. In such cases, you open the posterior capsule in a controlled fashion with SBCC, rather than allowing it to break in an uncontrolled way.

“The advantages of optic capture are huge,” Dr. Arbisser continues. “Number one: We know there’s no PCO. To this a surgeon might say, ‘A YAG laser’s no big deal.’ We have studies that show, however, that even in a case of a ‘clear’ 20/20 Snellen acuity, the posterior capsule causes straylight abnormalities. The vision is actually clearer, more reliable and simply better without a posterior capsule, with the lens in Berger’s space, than with a posterior capsule. Therefore, you get better vision to start with in SBCC. Number two: There’s no second period of visual degredation until you finally decide that the vision is bad enough and meets Medicare’s requirements for a secondary [YAG] procedure. This could be crucial in the developing world, where it might be impossible to come back for a YAG. Number three: When we do a YAG laser posterior capsulotomy, we almost invariably rupture the anterior hyaloid. That’s why we have an increased incidence of retinal tears and detachments afterward, particularly in high myopes. Number four: There’s an increase in IOP after a YAG, and often glaucoma patients have glaucoma that’s more difficult to control thereafter. So, besides avoiding the visual disability of PCO and the need for a second procedure—not to mention the cost of that procedure—the primary advantage is that SBCC stabilizes our anterior and posterior segment separation forever. I think this will impact not only the rate of retinal detachment, but the progression of diabetic retinopathy, the incidence of CME—particularly in patients with uveitis—and will block the prostaglandins from the anterior chamber to the posterior.”

Possible Disadvantages

Dr. Arbisser says the potential downsides of the procedure include the learning curve, the ramifications of a future IOL exchange and economics.

• Learning curve. “Dr. Menapace declared the learning curve to be about 150 cases,” Dr. Arbisser says. “Before I retired from patient care, I did about 80 and felt very comfortable with it. I had two complications. One complication occurred in a pediatric intumescent cataract in which I inadvertently opened the anterior hyaloid along with the anterior capsule. I believe there was no Berger’s space—even potentially—there. In response, I performed an anterior vitrectomy, which would be done routinely in such a case, and put the lens in the sulcus and performed anterior optic capture. The other complication occurred as I was trying to optic capture through the posterior capsulorhexis. I had made the capsulorhexis a little too small. I was using a different lens and was hoping to emulate what Dr. Menapace was doing and unfortunately broke the edge of the posterior capsulorhexis. The haptics remained in the bag and I captured the optic above the anterior capsulotomy. There was no vitreous prolapse.

“A femtosecond laser might be a way to make the learning curve easier,” Dr. Arbisser adds. “With the femto, it’s possible to make a posterior capsulorhexis that’s hyaloid-sparing. For example, Burkhard Dick has found that 72 percent of adults can have their anterior hyaloid and posterior capsule visualized, and a posterior capsulotomy done easily, with the Catalys laser.1 Interestingly, this can be done in 100 percent of patients with axial lengths over 25 mm, who might be the people who need it most. Dr. Dick found that every capsule scrolled out of the way by day one postop, and there was no vitreous prolapse in his series.”

Alexandria, La., surgeon R. Bruce Wallace says that some steps of the procedure could risk complications. “When you make a posterior capsulotomy, there’s the possibility you’ll disturb the vitreous face,” he says. “That would mean that it’s possible for some strands to get into the anterior chamber as you pull the needle out. This wouldn’t be a common situation, though. Also, as postop capsular contraction occurs, there may be a risk of IOL optic decentration.”

• Anterior vitrectomy. If SBCC were performed and a lens exchange was subsequently required, Dr. Arbisser says an anterior vitrectomy, something surgeons obviously usually try to avoid whenever possible, “would be a sure thing.”

“I think we’d do a one-port, pars plana, limited anterior vitrectomy,” she explains. “And, using the vitrector, we’d poke the lens back and then immediately place OVD to cover any of the area of the open capsule so there’d be no vitreous prolapse. We could then go about the exchange.”

Dr. Wallace doesn’t think this would be common, but is something to consider. “Exchanges don’t happen frequently,” he says. “And, in the world of cataract surgery, with a lot of people paying out-of-pocket for premium procedures, many patients can have LASIK to correct postop power problems. But, on occasion, LASIK isn’t an option, such as in situations in which the patient had LASIK previously or needs a significant power change. In those cases, you’d have the vitreous to worry about.”

• Economic factors. Not to put too fine a point on it: Almost half of cataract-surgery patients need a YAG capsulotomy, which is an extra reimbursement stream for the surgeon. SBCC does away with the need for YAG. “Though the world in general and any socialized medicine scheme in particular stand to benefit greatly by eliminating millions of secondary procedures,” says Dr. Arbisser, “we as ophthalmologists enjoy and count on the secondary reimbusement, so it’s very difficult to convince ophthalmologists in the United States to do this.”

For surgeons interested in learning more about SBCC, Dr. Arbisser will be a co-instructor at a course on it during Monday’s session at this year’s Academy meeting in New Orleans. REVIEW

Drs. Arbisser and Wallace have no financial interest in any of the products mentioned in the article.

1. Haeussler-Sinangin Y, Schultz T, Holtmann E, Dick HB. Primary posterior capsulotomy in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery: In vivo spectral-domain optical coherence tomography study. J Cataract Refract Surg 2016;42:9:1339-1344.