Most dry-eye patients respond to one of the first several medications initiated. However, there is a subset of patients who have long-standing dry eye that has resisted treatment. These cases are typically referred to a corneal specialist.

According to Brad Kligman, MD, who is in practice in Manhasset, New York, “The first step in caring for these patients is just having the patience to do so,” he says. “It can take a lot of time to get to the bottom of the problem, so just understanding that you need to talk to these patients at length and kind of hold their hand through the treatment is important.”

Establishing a Diagnosis

According to Dr. Kligman, when a patient is referred to his practice for dry eye that hasn’t responded to treatment, the first step is to take a very careful history. “It’s important to understand exactly what his or her symptoms are,” he notes. “Is it a burning or stinging? Is it blurry vision?”

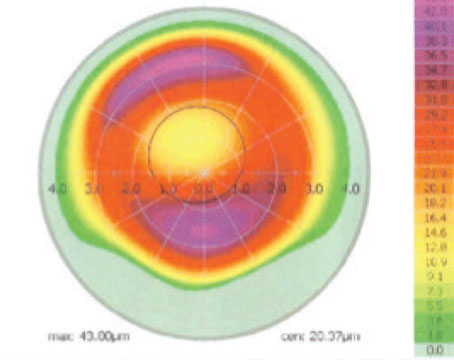

|

| Figure 1. This eye with SLK demonstrates a leash of conjunctival injection superiorly that stains with lissamine green dye. This diagnosis will be missed if the patient isn’t asked to look down and the superior conjunctiva isn’t specifically examined. (All images: Christopher J. Rapuano, MD.) |

Additionally, he recommends asking what time of day the patient experiences symptoms and whether he or she wears contact lenses. “Make sure to find out what types of lenses they’re wearing, how long they wear them, and whether they are sleeping in their lenses,” he says. “Those things don’t always get asked right away, and that can lead you to a delay in diagnosis. You want to ask about their sleeping habits and whether they have symptoms in both eyes or only one. If they only sleep on one side, that can point you to a different diagnosis. You want to get to the root of the problem and not just cover up symptoms.”

The next step is an exam that focuses on all parts of the eye. Start with the eyelids to determine how easily meibum is expressed. “When you talk about dry eye, patients assume it’s because the eye isn’t making enough tears,” Dr. Kligman says. “But the majority of dry eye is evaporative, where you’re not getting that good oil layer to hold the tears in place. So, I really focus on the lids and see if targeting lipid secretion will lead to resolution of symptoms. I also find it very important to flip the eyelids. That will let you know if there are allergies or signs of chronic infection. I often discover floppy-eyelid syndrome in these patients. When you’re manipulating the lids, see how easy it is to pull the lid away from the eye. That can point towards floppy-eyelid syndrome. If the lids are loose, pillows can physically push the eyes open during sleep and cause physical irritation. If you make patients aware of it, they can try to change their sleeping habits and add protective ointments or shields. That alone can lead to resolution of their symptoms.”

Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, in practice at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, adds that dryness resulting from floppy eyelids tends to be worse in the morning, while aqueous deficiency dry-eye symptoms tend to be worse at night. “Another diagnosis that you can make from flipping the eyelids and having the patient look down is superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis,” he says. “This condition is missed all the time and has symptoms very similar to dry eye.”

Dr. Kligman adds that the finding of floppy eyelids can also lead to a diagnosis of sleep apnea. “This is one way that we, as ophthalmologists, can help diagnose systemic disease,” he avers. “This not only helps their eyes feel better but can also potentially save lives down the road, because sleep apnea can lead to serious pulmonary and cardiac conditions. I’ve diagnosed dozens of people with sleep apnea just based on an exam for what they thought was dry-eye syndrome.”

Another component of a careful exam is to stain the cornea. “With contact lens wearers, you actually want to wait a little bit longer with the staining because that can bring out a very specific pattern that will tell you that it’s not really dry eye,” Dr. Kligman notes. “It can be corneal limbal stem cell deficiency, which is more common than people think, but you need to take the time and look for it. This also changes the treatment protocol, because patients really just need to completely stay out of their contact lenses. If you treat it with drops and medications but they still wear the contact lenses, it will never get better. It can actually become a vision-threatening condition. You’re looking for little comma-shaped areas of staining emanating from the limbus rather than the discrete dots that we typically associate with dry eye.”

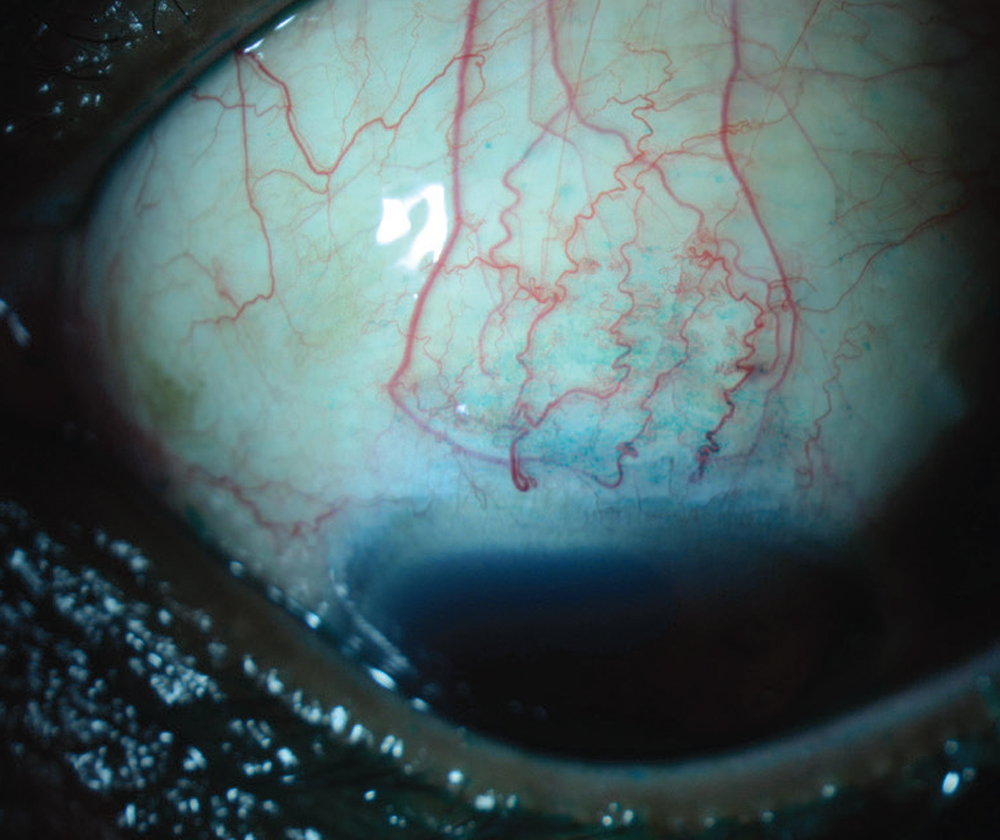

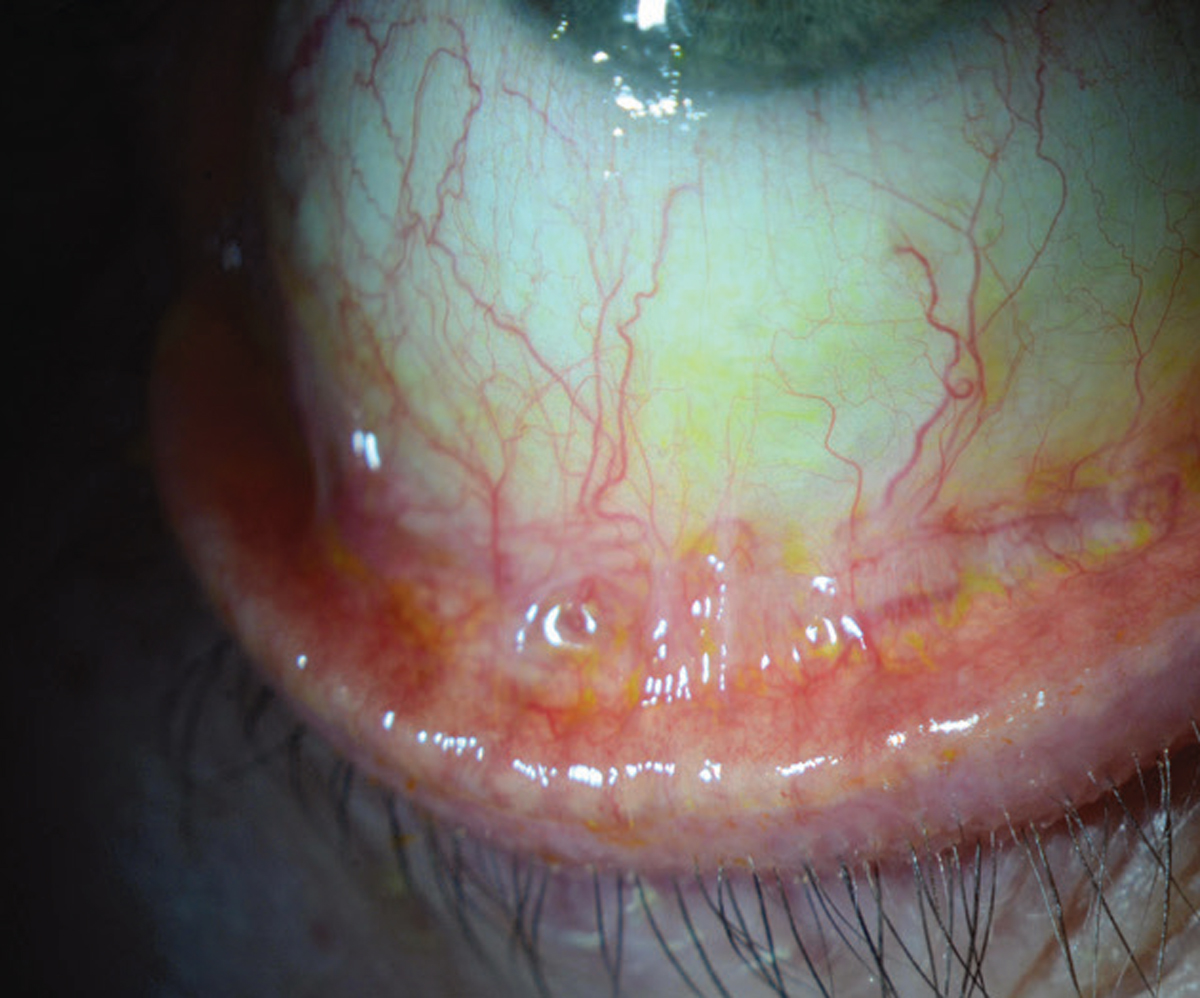

|

| Figure 2. This eye has significant loose, excess conjunctival tissue at the inferior limbus consistent with conjunctivochalasis. The excess conjunctival tissue may need to be excised to improve dry-eye symptoms. |

It’s also important to examine the conjunctiva. Often, when patients complain of a foreign body sensation, it’s due to conjunctivochalasis, a laxity and redundancy of the conjunctiva. “When they’re blinking, they’re actually feeling the conjunctiva between their lids,” Dr. Kligman explains. “This is another instance where the traditional treatments for dry eye won’t necessarily make the symptoms better. In these cases, we might need to perform a procedure to shrink or excise the redundant conjunctiva.”

Dr. Rapuano agrees that conjunctivochalasis is a fairly common diagnosis that’s often missed, and these patients often get treated for dry eye without significant improvement. Another one is mucous membrane pemphigoid. “Have the patient look up and look at the inferior fornix to see if there’s inferior fornix shortening or scarring of the inferior conjunctiva,” he explains. “This tends to occur in older patients, more in women than in men, and it’s a potentially blinding disease. Obviously, when it’s severe, it’s much easier to make the diagnosis, but blinding disease starts off as a mild disease. If you make the diagnosis early, you can treat these patients a lot better.”

After all these evaluations, it may turn out to be a more typical aqueous deficient dry eye. “Those alone are kind of rare, so you have to dig a little bit deeper to find out why they’re not producing tears,” Dr. Rapuano advises. “If their Schirmer score is less than 5 mm and they have really bad staining across their corneas, that’s when you want to get into a more targeted medical history and find out if they have joint pain, muscle aches or a history of rheumatologic disease. Either you or a rheumatologist might want to run an inflammatory lab panel to find out if the patient has an autoimmune or rheumatologic disease that might be contributing to dry eye.”

Neurotrophic keratitis and exposure keratitis are other conditions to watch for. “Some people’s eyes just don’t close very well, they don’t blink very well, and they’re open at nighttime, causing the eyes to get dried out,” Dr. Rapuano says. “So, it’s not necessarily that they’re not making a lot of tears-—they’re just getting dried out during the nighttime.”

If a patient has significant chalazia, especially in one eye, be sure to flip the eyelid and examine it for signs of sebaceous carcinoma. “This is skin cancer of the eyelid and the underside of the conjunctiva. It’s rare, but it’s potentially blinding—if not lethal,” Dr. Rapuano says. “That’s at the very extreme, of course, and that’s more blepharitis differential than dry-eye differential.”

Treatments

According to Dr. Kligman, when initiating treatment, make sure that patients understand that it’ll be a process and that you will be working with them long-term. “This is a chronic condition that needs to be managed, like blood pressure or cholesterol,” he says. “That helps put them in the mindset of really committing and following through with the recommendations. It’s important to set expectations with patients that it can be a long process, but you’re going to be there to see them through these different treatments and see what works.”

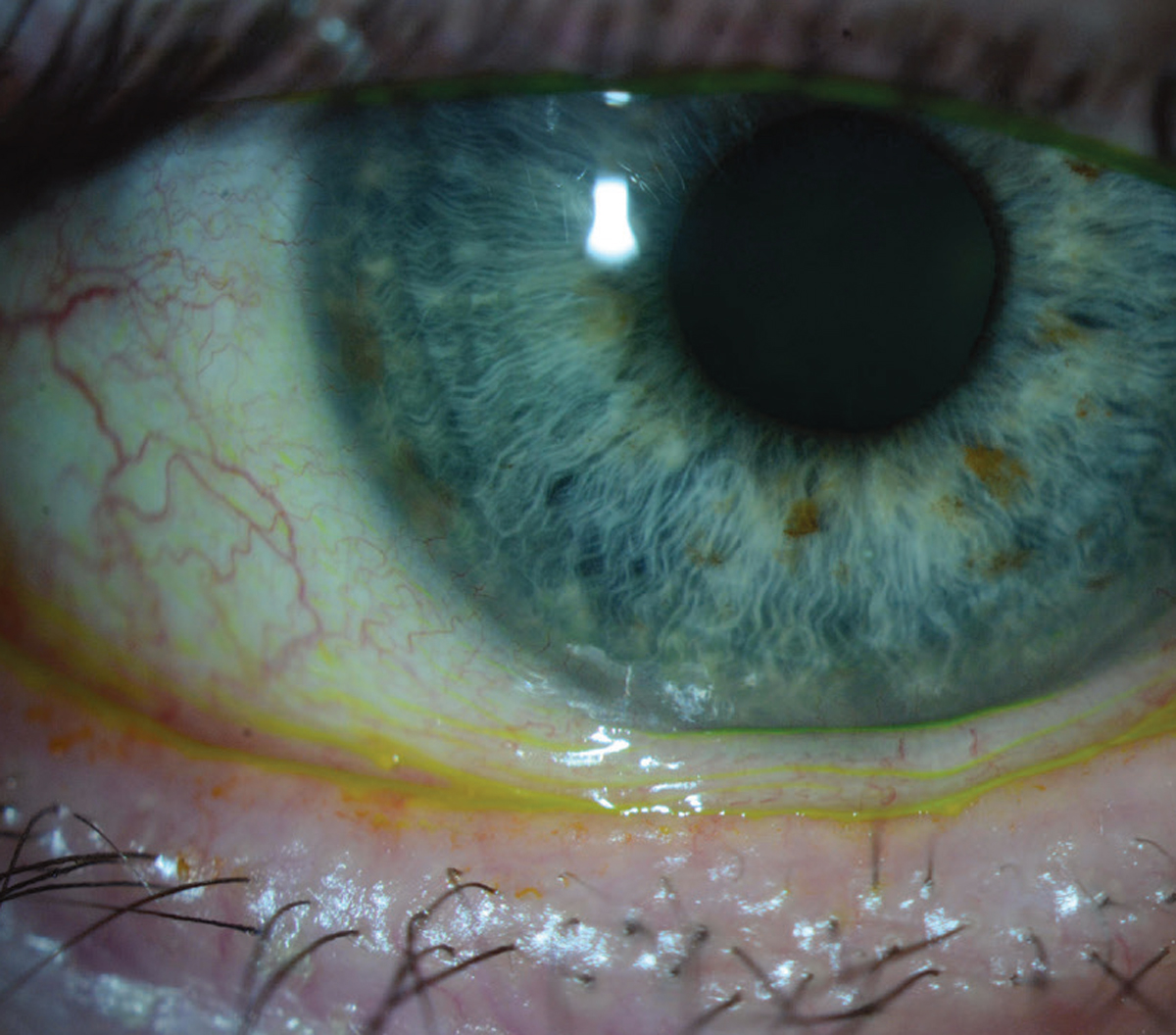

|

| Figure 3. Inferior forniceal foreshortening is apparent in this eye, but will only be diagnosed if the patient is asked to look up and the inferior fornix is examined. This patient may need to be worked up for mucous membrane pemphigoid. |

Fortunately, there are many treatments available for dry eye. For a while, the mainstays were cyclosporine and lifitegrast. “Tyrvaya (varenicline) nasal spray is a new option, and there are several products in the pipeline,” Dr. Kligman says. “The good thing is, in the past five years, we have had a big jump in available treatments. Eysuvis also recently became FDA-approved; that’s another formulation of loteprednol that’s approved for pulse treatment of dry-eye flares. We now have a steroid formulation in Eysuvis that has been studied in this specific population. We can more confidently prescribe to patients and not worry about pressure spikes quite as much.” Other recent additions include Klarity-C (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 1%, ImprimisRx) and Cequa (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.09%, Sun Ophthalmics).

For evaporative dry-eye disease patients who have blepharitis and meibomitis, there are several tools and procedures that can be performed to help open the glands. Patients can start with lid scrubs, lid sprays and at-home warm compresses. “If those aren’t fully successful,” Dr. Kligman says, “then you can move on to procedures that are done in the office, like BlephEx, which physically removes the build-up of scurf at the lash bases, and you can use heating and expression devices, like iLux2, LipiFlow and TearCare, which help heat and express the glands all at once and help to reset these meibomian glands to get people back to producing healthy meibum that actually flows out of the lids.”

Dr. Rapuano adds that other treatment options include punctal plugs, steroid drops and serum tears. “You can then proceed to scleral lenses in bad dry-eye patients,” he notes. “In the really bad ones, especially if the patients are older and are less concerned about cosmetics, you can do a small permanent lateral tarsorrhaphy. I’ve done that in several patients who have Sjogren’s syndrome, where they get ulcerations or scratches in the eye. You can just do a little lateral tarsorrhaphy, and that significantly decreases the palpebral fissure, so there’s much less evaporation.”

According to Stephen Pflugfelder, MD, who is in practice at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome require aggressive therapy. “These patients can be in the acute phase or the chronic phase,” he says. “It’s usually during the chronic phase that most doctors end up seeing these patients. At that point, they can have a lot of conjunctival and lid margin scarring, irregular lid margins, lashes that grow in (trichiasis) and no tear production. And, in some cases, because the lids are so irregular, they can develop corneal epithelial defects and even corneal ulcers. If patients have lids that turn in, they’ll need surgery to rotate the lid margin out, away from the eye. They may need what’s called a mucus membrane graft to resurface the back of their eyelids. They usually need serum or plasma drops, and they usually need scleral contact lenses.”

Another condition is graft-versus-host disease, which can develop in patients who’ve had allogeneic bone marrow transplants. “By about 90 days out, 40 to 50 percent of patients will experience severe dry eye, and they can also experience eyelid scarring,” Dr. Pflugfelder says. “We first try conventional dry-eye treatments, but they don’t often work. These patients may also require serum or plasma drops and scleral lenses to feel better. Anti-inflammatory treatments, like cyclosporine or topical corticosteroids, can also be helpful.”

Neurotrophic keratitis can result in reduced corneal or ocular surface sensation due to nerve damage or degeneration. This can be a result of herpes, chemical injuries, neurosurgery, diabetes and some neurodegenerative diseases. “In addition to standard dry-eye treatment, these patients can be treated with cenegermin (Oxervate, Dompé), which is recombinant nerve growth factor,” Dr. Pflugfelder says.

According to Dr. Kligman, these treatments can often be life-changing for patients who are struggling with dry eye. “For those physicians willing to take the time and get the history and do the really careful exam,” he says,“they can create a very loyal following of happy patients who have been suffering for a long time. You can potentially identify an underlying condition that was overlooked previously and really improve these patients’ quality of life.”

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Kligman receives research funding from Dompé, the producer of Oxervate. Dr. Rapuano is a consultant for Dompé, Oyster Point, Sight Sciences and Tarsus. Dr. Pflugfelder has no relevant financial interests.