Imagine taking months to build a house—painstakingly selecting everything from the flooring and furniture to the light fixtures and drawer pulls—only to have fire sweep through and gut the place. This is a lot like postop inflammation after cataract surgery; you did everything right and got a good result, but now the inflammation threatens all of your hard work. While most inflammation after routine cataract surgery is minimal and resolves relatively quickly, persistent inflammation after cataract surgery is a complication that’s been reported in 0.24 percent to 7.3 percent of cases.1 In this article, surgeons discuss the ways they use to keep inflammation at bay.

|

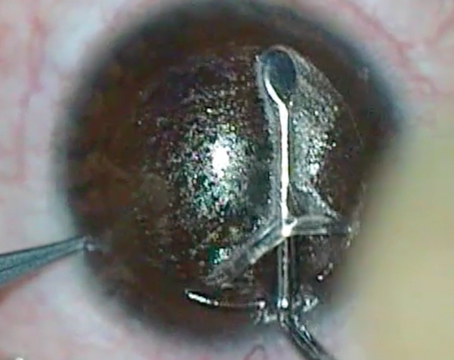

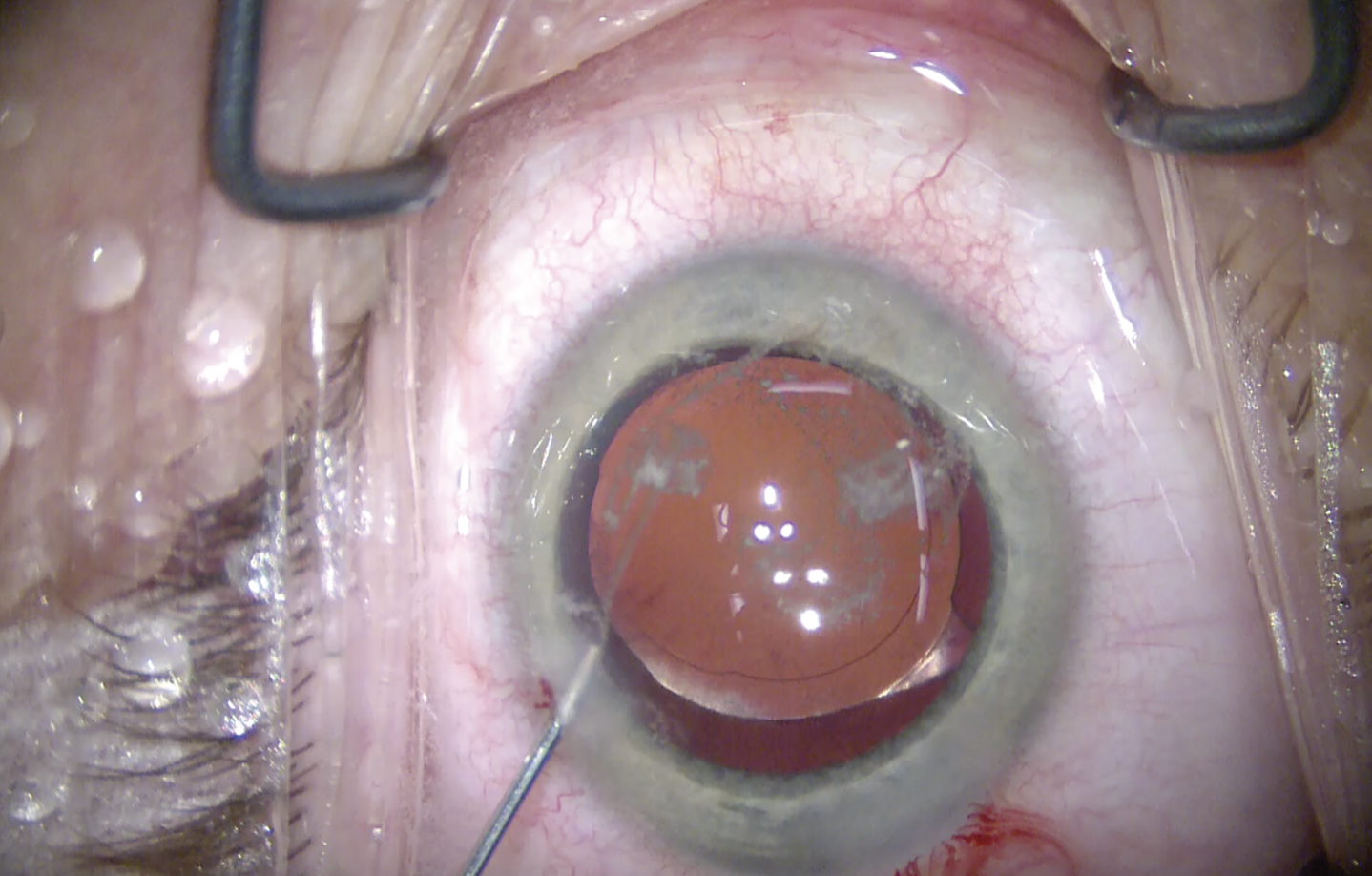

| A strong inflammatory response after surgery. (Images courtesy of Uday Devgan, MD, from Cataractcoach.com.) |

Risks for Postop Inflammation

In a study conducted at the Montefiore Medical Center in New York, persistent inflammation after complex cataract surgery was observed in nine of 156 cases (5.7 percent) regardless of gender, age, ethnicity or intraoperative use of iris-retention devices, and it was best predicted by the use of a prostaglandin analogue at the time of surgery.1

According to Andrew A. Kao, MD, some cataract patients are more prone to developing postop inflammation than others. “For example, patients with a history of uveitis or diabetes are more at risk for postoperative macular edema,” says Dr. Kao, who is in practice in Bakersfield, Calif.

Los Angeles’ Uday Devgan, MD adds that more inflammation occurs in patients with longer duration of surgery, dense cataract that requires more ultrasonic energy to break up, more fluidic flow during surgery, complications during surgery, retained lens material, younger age (younger patients have more inflammation typically than older patients), and a genetic variation of inflammatory response.

Michael Saidel, MD, who is in practice in Petaluma, California, agrees. “Cataract surgery itself causes inflammation,” he notes. “Another cause of runaway inflammation is that the postoperative anti-inflammatory management was insufficient, whether because of patient non-compliance or surgeon management. Additionally, it can be due to residual lens material left behind after the cataract surgery and lodged in the sulcus, in the angle, or elsewhere in the eye. It can also be due to complications from cataract surgery.”

|

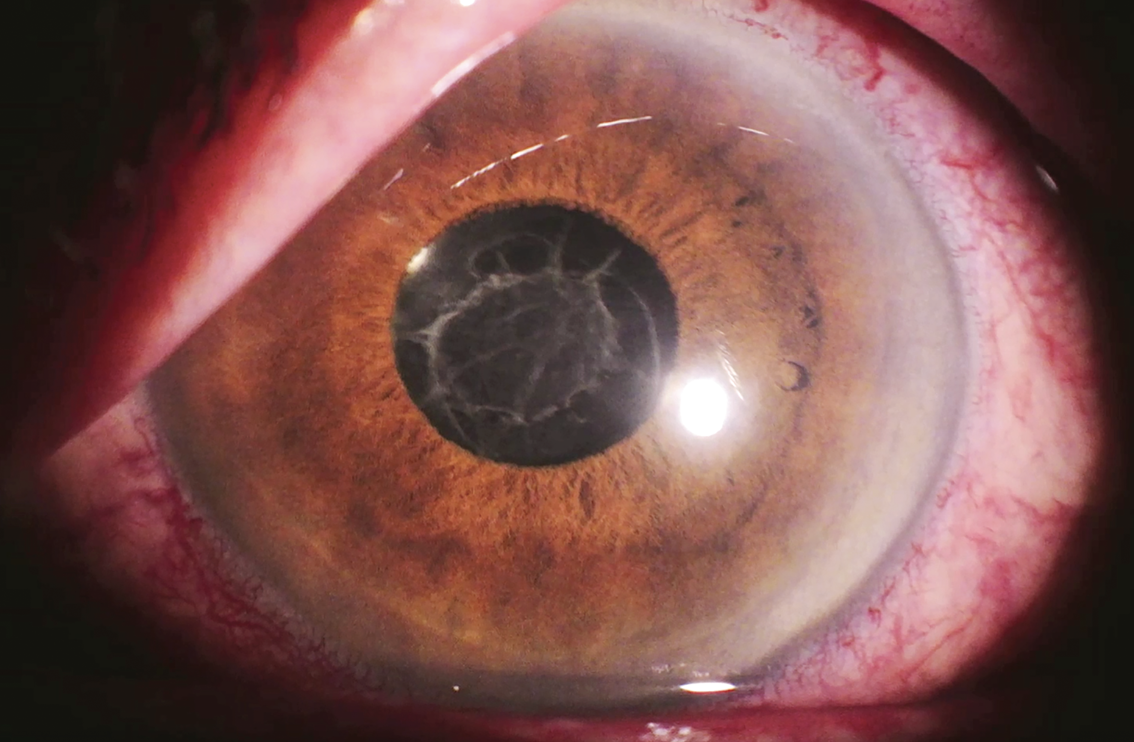

| Triamcinolone being injected into the anterior chamber. |

Inflammation After Routine Surgery

Surgeons say they have their own preferred methods of delivering corticosteroids or nonsteroidals postop.

Dr. Devgan’s treatment regimen for routine cataract surgery is topical steroid drops, usually prednisolone acetate, three times a day for two weeks.

“One pearl is to inject a little preservative-free triamcinolone (0.5 mg) into the anterior chamber at the end of the case to quickly quell inflammation in the immediate postop period,” Dr. Devgan says.

Drs. Saidel and Kao have switched from commercially available drops to a compounded medication in an effort to improve patient adherence to therapy and to decrease patient costs. “For routine patients with no history of uveitis or any other ocular pathology, I use a combination of prednisolone, gatifloxacin or moxifloxacin antibiotic, and an NSAID, typically bromfenac, in combination,” Dr. Saidel says. “They’re compounded and used three times a day for approximately 3.5 weeks.”

Dr. Kao’s practice also uses a compounded fluoroquinolone, steroid and NSAID combination. “We tell patients that the medications cost a flat fee of $40, and the compounding pharmacy sends the medication directly to the patient’s house, so there are no issues of patients neglecting to get the drops,” he says. “It also enabled us to simplify our drop regimen. Instead of instilling each drop three or four times a day, we simplified it to where they can just instill this compounded drop twice a day for two weeks and then once a day for two weeks. This has made patients a lot more adherent to treatment, and we haven’t seen any increase in rebound iritis or macular edema using this regimen.”

Using three separate medications can be confusing for patients, especially elderly patients. “Even with our simplified regimen, some patients still have questions,” Dr. Kao says.

Because non-compliance is such a significant issue in this patient population, researchers are studying new ways to deliver medications. One example is a liposomal drug delivery system that’s currently in a Phase I/II trial.2 The study concluded that liposomal prednisolone phosphate, administered as a single subconjunctival injection intraoperatively, can be a safe and effective treatment for post-cataract surgery inflammation.

All patients in this trial received a single injection of subconjunctival liposomal prednisolone phosphate for the treatment of postop inflammation. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of eyes with an anterior chamber cell count of zero at one month postop. Five patients were enrolled in this study, and the percentage of patients with anterior chamber cell grading of zero was zero percent at day one, 80 percent at week one, 80 percent at one month, and 100 percent at month two after cataract surgery. Compared to baseline, mean laser flare photometry readings were significantly elevated at week one after cataract surgery (48.8 ±18.9) decreased to 25.8 ±9.2 at month one and returned to baseline by month two (10.9 ±5.1).2 There were no ocular or non-ocular adverse events.

Non-Routine Patients

Patients who experience significant amounts of inflammation fall into one of two categories: those with pre-existing conditions who are expected to have issues with inflammation and those who simply don’t respond to initial treatment.

According to Dr. Saidel, patients in these two categories are handled very differently. “If I have a patient with uveitis, I want to reach a level of quiescence of uveitis for three months prior to surgery,” he says. “This typically means a zero-tolerance policy for anterior chamber inflammation and inflammation in the rest of the eye. The physician should be checking the anterior chamber in a darkened room, under high power, ensuring that there are no cells in the anterior chamber for three months prior to the surgery. Whatever it is that got the patient into this remission should be continued through the preoperative and postoperative period.”

Prior to surgery, he’ll start these patients on topical steroids and topical NSAIDs for a minimum of three days immediately preoperatively. “I will usually, although not universally, use systemic steroids starting three days prior to the surgery and for a minimum of a week after, although frequently I’ll taper those over the course of a month,” he says. “In addition, I’ll take extra measures, including a stronger steroid drop, like difluprednate, as opposed to my usual combo drop, as well as using intracameral slow-release dexamethasone, if that’s appropriate. In some patients, I’ll also perform a posterior sub-Tenon’s or periocular steroid injection, and steroids are titrated based on patients’ need and their risk of elevated intraocular pressure, as well as concerns of elevated blood sugar in diabetics or any patient who may suffer from those conditions. So, the group of patients with known intraocular inflammation are managed very differently than patients who have a surprise intraocular inflammation.”

For those with unusual or resistant inflammation with no pre-existing conditions, Dr. Devgan increases the dosing of his regimen to six times per day, and he will sometimes consider locally injected steroids. “Patients rarely require systemic steroids,” he explains.

Dr. Kao adds that he’ll switch patients who don’t respond to initial therapy to a commercially available drop, like prednisolone or difluprednate, and increase the frequency of the drop. “If I expect a patient to have more inflammation than usual, like someone with a history of uveitis, then I’ll treat him or her preemptively with a commercially available drop preoperatively so that we try to quiet down any inflammation before it starts.”

Dr. Saidel tailors treatment of these patients based on the cause. “If the cause is a complication of surgery, treatment is going to be different than someone who has just a simple rebound iritis,” he says. “The most common postoperative inflammation we see is rebound iritis, which is typically managed in my practice with topical steroids. I’ll sometimes do a systemic work-up for uveitis in the patient who doesn’t respond as expected to typical topical treatment.”

According to Dr. Saidel, the best way to prevent postoperative inflammation is to treat it before it starts. “And, for patients who are at risk, being aggressive with localized immunosuppression has been shown to produce better outcomes,” he says. “So, prevention is the key. Performing a good examination of the anterior chamber in a darkened room is crucial to quantifying how much inflammation a patient really has.”

He adds that, for the patient who has a history of uveitis and prior intraocular inflammation, it’s important to perform OCT and a thorough exam of the retina prior to surgery. “In a patient who has unexpected postoperative inflammation, examining the posterior segment, as well as performing an OCT, is important to rule out other pathologies, including cystoid macular edema,” Dr. Saidel says. “In addition, in patients with posterior pathologies, I’ll refer to a retina specialist.”

Intraoperative “Dropless” Regimen

Many ophthalmologists are moving to intraoperative medication therapy to address the noncompliance issue. “The biggest argument for this is patients being unable to stick to the drop regimen,” says Dr. Kao. “Many ophthalmologists are prescribing three drops that are being used multiple times a day. It’s too confusing for patients. In my practice, instead of going completely dropless, we switched to a combined drop treatment, which has been really beneficial for our patients.”

He says that his practice hasn’t moved to dropless surgery, due to concerns about side effects, as well as cost. “We haven’t seen the need to switch over because we have a postop drop regimen that works and that patients are relatively adherent to,” Dr. Kao explains. “Dropless regimens can result in floaters for weeks after surgery, which can be undesirable for patients undergoing refractive cataract surgery. Additionally, cost of the dropless medications has to be considered if you own your own surgery center. However, in the future, if there are commercially available intraoperative medication regimens that are available and more affordable, we would consider switching. Right now, we haven’t found dropless cataract surgery to be necessary for our patients.”

Comparing Treatments

A recent study conducted in Denmark investigated whether a combination of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids were superior in controlling early postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery compared with topical NSAIDs alone and with dropless surgery where a sub-Tenon’s depot of steroid was placed during surgery.3 The study found no differences between groups randomized to NSAID monotherapy or combination of NSAID and steroid in controlling early inflammation after cataract surgery, but sub-Tenon’s depot of dexamethasone was less efficient. Initiating prophylactic drops prior to surgery didn’t influence early postoperative anterior chamber inflammation.

In this study, 456 patients were randomized to one of five regimens: ketorolac and prednisolone eyedrops combined either preoperatively (control group) or postoperatively; ketorolac monotherapy either preoperatively (control group) or postoperatively; or sub-Tenon’s depot of dexamethasone (dropless group). All drops were used until three weeks postoperatively, starting three days preoperatively in the preoperative groups and on the day of surgery in the postoperative groups.

Flare increased significantly more in the dropless group compared with the control group that received a steroid and NSAID combination preoperatively. Intraocular pressure decreased in all groups but decreased significantly less in groups receiving prednisolone eyedrops both preoperatively and postoperatively compared with NSAID monotherapy and dropless groups. Compared with the control group, no differences in postoperative visual acuity were observed.

Drs. Devgan, Kao and Saidel do not have a financial interest in any of the products mentioned.

1. Panvini AR, Busingye J. Persistent inflammation after complex cataract surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018;59:4774.

2. Wong CW, Wong E, Metselaar JM, Storm G, Wong TT. Liposomal drug delivery system for anti-inflammatory treatment after cataract surgery: A phase I/II clinical trial. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022;12:1:7-14.

3. Erichsen JH, Forman JL, Holm LM, Kessel L. Effect of anti-inflammatory regimen on early postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47:3:323-330.