Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of herpes simplex virus keratitis in a young child is significantly more difficult than in an adult. At baseline, kids are more difficult to examine and require additional time. With the added discomfort of the infection and the photophobia that often accompanies it, the exam is often challenging. In

|

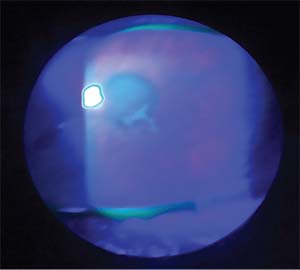

| Figure 1. The findings in early HSV keratitis can be subtle, as noted by this lesion that doesn’t have the full dendritic staining pattern but is highly suspicious. |

These challenges continue in follow-up when assessing the child’s response to treatment and the further clinical course of the disease.

Making the diagnosis of an HSV infection is even more important if the child is in the neonatal period, since the risk of fatal encephalitis or disseminated disease is much higher. The rate of HSV infection in the neonate is reported to be one out of 3,500 births.1 Treating these patients as early as possible with intravenous antivirals has reduced morbidity from skin, eye and/or mouth infections (often called SEM disease). The rate of developmental delay in these SEM patients at 12 months of age has been reduced from 38 percent to less than 2 percent.2

Much of our understanding of and treatments for HSV keratitis are derived from the landmark Herpetic Eye Disease Study. It’s important to note, however, that HEDS only included patients who were 12 years of age or older.3 Therefore, the study excluded patients in the amblyogenic period and those younger patients that may have an atypical presentation or greater inflammatory response to the virus.

Comparing studies of pediatric HSV keratitis patients and those included in HEDS shows some striking differences. In HEDS the recurrence rate of all forms of HSV keratitis was 32 percent,3 while for pediatric patients in other studies it ranges from 33 to 80 percent.4-10 Compiling all of the pediatric patients involved in the studies shows a cumulative recurrence rate of 51 percent. Thus, while one-third of adult patients will have a recurrence of their disease, more than half of pediatric patients will experience a recurrence without antiviral suppressive treatment.

The other major difference in HSV keratitis between pediatric and adult patients is in the rate of bilateral involvement. Studies in adults have consistently demonstrated that bilateral HSV ocular disease is a rare entity, often being reported in the low single digits, usually less than 3 percent.11 Only a handful of older studies show a bilateral rate of disease approaching 10 percent.12,13

In the pediatric population, however, the reported occurrence rate of bilateral disease ranges from zero to 26 percent.4-10 This is especially important to note, since many pediatric patients, 30 percent by some accounts,14 are misdiagnosed. It’s usually not until there is delayed resolution of the redness or notable disease progression that the condition is again investigated. This additional time without antivirals or topical steroids can be devastating, since visually significant scarring with induced irregular astigmatism can develop.

To summarize the key points of making the diagnosis in the pediatric population, the clinician should:

• be aware that there’s a higher risk of recurrent disease;

• carry a high suspicion in cases of unilateral disease and not dismiss the possibility of HSV if bilateral disease presents; and

• know that a greater amount of inflammation and amblyogenic scarring from opacity and astigmatism can occur.

Treatment

Current treatment protocols for HSV keratitis are also derived from HEDS. But again, there are differences between an adult population and a pediatric one. One of the major findings in HEDS was that topical and oral antivirals were essentially equivalent in preventing progression from epithelial keratitis to stromal keratitis.15 However, this is assuming that you have the proper concentration of a topical medication within the eye. It’s fairly common for children to tear or cry after having a drop put into their eyes. This can dilute the medication and possibly reduce its effectiveness. For that reason, the recommendation in the pediatric population strongly leans towards using oral antivirals.8

• Treatment—active infection. In adults, the oral treatment protocol for HSV keratitis is acyclovir 400 mg by mouth five times per day.16 For pediatric patients, adjustments for weight and other factors must be made. The range that was used in the study by Gary

|

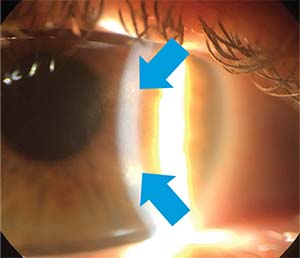

| Figure 2. A Wessley immune ring is seen in this case of HSV disciform keratitis. |

• Treatment—suppression. HEDS demonstrated that using acyclovir 400 mg by mouth twice daily reduced recurrence rates from 32 percent to 19 percent and was most beneficial in those who had a history of previous recurrences.17 For children the suppression dose was found to range between 12 to 20 mg/kg/day.8 Reaching the appropriate suppression dose for each child did involve some trial and error on the part of the investigators. While tapering the acyclovir down from the treatment dose, three out of their seven pediatric patients had recurrences. This required them to increase the dose back to treatment levels and then begin the tapering process again. They then tapered more slowly, exercising additional caution when they approached the dosage at which there was a recurrence previously.

A more recent study was conducted by Indiana University’s Shaohui Liu, MD, PhD. She and her colleagues chose to use dosages in 100-mg intervals related to the commercially available acyclovir suspension 200 mg/5 ml. The dosages used were:

• infants (up to 18 months), 100 mg (2.5 ml) t.i.d for treatment or b.i.d. for prophylaxis;

• toddlers (18 months to 3 years), 200 mg (5 ml) t.i.d. (treatment) or b.i.d. (prophylactic);

• young children (3 to 5 years), 300 mg (7.5 ml) t.i.d. (treatment) or b.i.d. (prophylactic); and

• older children (6 years and older), 400 mg (10 ml) t.i.d. (treatment) or b.i.d. (prophylactic).18

However, the authors admit that the dosing will change as the child grows, referencing one case where a growth spurt led to a series of recurrences due to insufficient suppression of HSV. This, again, indicates that there is not a “one-dose-fits-all” approach to the pediatric population. Simplicity in dosing may increase patient compliance with the treatment, but you have to ensure that the dose is adequate for each child, as there will occasionally be outliers.

• Treatment—topical corticosteroids. The treatment of stromal, endothelial and kerato-uveitic disease has long involved topical corticosteroids. However, treating a patient with topical corticosteroids while he or she has active epithelial disease remains contraindicated. In the pediatric population there is no study evaluating the dosage or duration of treatment. Many of the pediatric studies comment about topical corticosteroid treatment as being used “according to the severity of the disease,”19 and then “adjusted according to the clinical response of each patient.”18 Again, the relied-upon information regarding the use of topical corticosteroids comes from the HEDS group. Keep in mind that HEDS only included patients 12 years of age or older.

In exploring the benefits and use of topical corticosteroids, the HEDS group performed a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. They looked at 106 patients treated with trifluridine 1% and a tapering regimen of a placebo or prednisolone phosphate for a 10-week period. The patients in the treatment arm started on prednisolone phosphate 1% eight times per day for one week, then tapering to six times per day for a week, then four times, then two times, then one time before cutting the concentration of the prednisolone phosphate to 0.125%. The taper was then continued at a rate of four times per day for a week, then two times per day for a week and then one time per day for two weeks, until the full 10-week taper was completed.

They demonstrated that the patients treated with topical corticosteroids had less progression of their disease and faster resolution. While some patients in the placebo group had delayed initiation of steroid treatment, they too benefited and showed delayed resolution—but equal vision compared to those in the treatment arm at six months follow-up.20 The main consequence was that almost 10 percent of the patients that were in the treatment arm had activation of epithelial disease, despite suppressive treatment with trifluridine.

The authors concluded that steroids were safe, beneficial and could have delayed initiation with close monitoring in adults. Since it is understood that children have a higher rate of inflammation with activation of the infection, one has to question the wait-and-see approach with initiating topical corticosteroids in the pediatric population. This is certainly an area that would benefit from additional studies. For now, one can hypothesize that treating the additional inflammation seen in the pediatric population aggressively and initiating corticosteroid treatment as early as possible (in conjunction with antivirals) for stromal, endothelial or kerato-uveitic disease could help improve these patients’ conditions more rapidly and prevent any further sequelae. In the HEDS study, 67 percent of the patients in both arms had vision of 20/40 or better in the affected eye at six months. For the pediatric population, this still poses a significant risk of amblyopia and would further encourage the prompt use of topical steroids to reduce the time that it takes for the eye to recover and have the best vision possible.

Outcomes

The risk of developing amblyopia due to corneal opacity or irregular astigmatism is very real and something that needs to be monitored as closely as the patient’s response to the treatment of the HSV keratitis itself. The largest recent study, by Mexico City’s Juan Carlos Serna-Ojeda, MD, shows that 51.3 percent of the patient group developed central corneal opacities and 8.7 percent developed irregular astigmatism greater than 2 D. This resulted in 30.2 percent of their patients developing amblyopia.19

In the study by Dr. Liu, 54 percent of the patient group developed a central corneal opacity and 28 percent developed a change in their astigmatism of greater than 2 D. While they don’t explicitly discuss the rates of amblyopia, they report that 26 percent had a best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or worse.17 The highest rate of amblyopia reported in recent studies was 66 percent.10

With a large portion of pediatric HSV patients developing amblyopia, it’s important to monitor them frequently for any changes in their vision in addition to aggressively treating the infection. Frequent refractions and instituting early amblyopia treatment can help prevent the loss of BCVA. If there’s a significant component of irregular

|

| Figure 3. Stromal scarring as seen at the slit lamp secondary to HSV stromal keratitis. |

In those cases where medical management isn’t sufficient and keratoplasty is needed, it’s important to know that antiviral prophylaxis is exceedingly important. In another study by Dr. Serna-Ojeda, he and his colleagues treated pediatric patients with six months of oral acyclovir at a suppression dose level before proceeding with keratoplasty. They then continued the acyclovir at the suppression dose indefinitely. In their retrospective case review, with a median follow-up of 49 months, they had no graft failures.21 The authors did mention that one of the biggest limitations to regaining vision was the amblyopia that had already developed. This leads to the common concern when considering a pediatric penetrating keratoplasty: the higher risk of graft failure in the younger patient versus the risk of continued amblyopia development.

Ultimately, though pediatric herpes keratitis can be challenging to diagnose and treat, the pediatric population benefits immensely from having the appropriate treatment initiated as soon as possible, since this limits the long-term sequelae of the disease. Current first-line treatment involves the use of oral antivirals and topical corticosteroids when appropriate. Close monitoring and follow-up is needed to assess the child’s response to the prescribed treatment and to catch any changes to BCVA as early as possible. REVIEW

Dr. Bert is an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Doheny Eye Center of UCLA, David Geffen School of Medicine.

1. Whitley RJ. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. J Med Virol 1993;Suppl 1:13–21.

2. Kimberlin DW, Whitley RJ. Neonatal herpes: What have we learned. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2005;16:1:7-16.

3. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med 1998;339:300-306.

4. Poirer RH. Herpetic ocular infections of childhood. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:704-706.

5. Colin J, Le Grignou M, Le Grignou A, et al. L’hepes oculaire de l’enfant. Ophthamologica 1982;184:1-5.

6. Beneish RG, Williams FR, Polomeno RC, et al. Herpes simplex keratitis and amblyopia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1987;24:94–96.

7. Beigi B, Algawi K, Foley-Nolan A, et al. Herpes simplex keratitis in children. Br J Opthalmol 1994;78:458-460.

8. Schwartz GS, Holland EJ. Oral acyclovir for the management of herpes simplex virus keratitis in children. Ophthalmology 2000;107:278-282.

9. Chong EM, Wilhelmus KR, Matoba AY, et al. Herpes simplex virus keratitis in children. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138:474-475.

10. Hsiao CH, Yeung L, Yeh LK, et al. Pediatric herpes simplex virus keratitis. Cornea 2009;28:3:249-53.

11. Wilhelmus KR, Falcon MG, Jones BR. Bilateral herpetic keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1981;65:385-387.

12. Norn MS. Dendritic (herpetic) keratitis I: Incidence, seasonal variations, recurrence rate, visual impairment, therapy. Acta Ophthalmol 1970;48:91-107.

13. Thygeson P, Kimura SJ, Hogan MJ. Observations on herpetic keratitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1956;64:375-88.

14. Revere K, Davidson SL. Update on management of herpes keratitis in children. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013;24:4:343-7.

15. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for the prevention of stromal keratitis or iritis in patients with herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. The Epithelial Keratitis Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115:6:703-12.

16. Collum LM, Akhtar J, McGettrick P. Oral acyclovir in herpetic keratitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K 1985;104(Pt. 6):629-32.

17. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Oral Acyclovir for Herpes Simplex Virus Eye Disease. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118:1030-1036.

18. Liu S, Pavan-Langston D, Colby KA. Pediatric herpes simplex of the anterior segment: Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Ophthalmology 2012;119:10:2003-8.

19. Serna-Ojeda JC, Ramirez-Miranda A, Navas A, Jimenez-Corona A, Graue-Hernandez EO. Herpes simplex virus disease of the anterior segment in children. Cornea 2015;34:Suppl 10:S68-71.

20. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, Kurinij N, Dawson CR, Jones DB, Barron BA, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101:12:1883-95

21. Serna-Ojeda JC, Loya-Garcia D, Navas A, Lichtinger A, Ramirez-Miranda A, Graue-Hernandez EO. Long-term outcomes of pediatric penetrating keratoplasty for herpes simplex virus keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2017;173:139-144.