Herpes simplex and herpes zoster viruses can have many ocular manifestations, some of which are serious and vision-threatening. Both conditions have the potential to be chronic and recurrent, as well. Here, experts share the protocols they use when dealing with these sometimes challenging cases.

Herpes Simplex

|

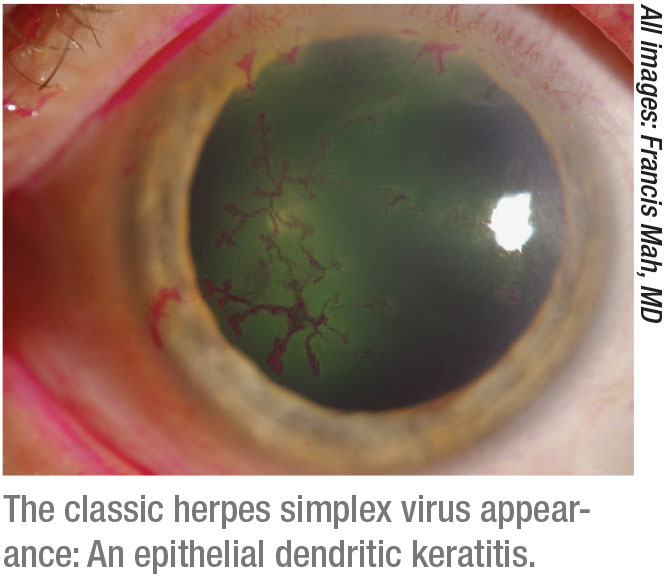

Cornea specialist Francis Mah, in practice in La Jolla, California, notes that the live virus can cause epithelial keratitis and other ocular manifestations. The classic herpes simplex presentation is a dendrite that can form on the surface of the cornea. The treatment for this is epithelial scraping with an instrument such as a Kimura spatula, along with trifluridine drops—which was a huge advance at the time they were introduced—and oral antivirals, such as acyclovir, valacyclovir and famciclovir, the most commonly used treatments among cornea specialists. A newer agent, ganciclovir gel, is also an option. “Typically, people will develop a dendrite when they’re run down, when they’ve traveled, and when they are stressed or sick,” he says. “Sunlight can also stimulate it. Dendrites don’t cause much pain. The main symptom will be a change in the patient’s vision.”

Bennie Jeng, MD, who is in practice in Baltimore, prefers to treat herpes simplex keratitis with oral acyclovir or oral valacyclovir, rather than topical ganciclovir or trifluridine. “Ganciclovir is very expensive, and trifluridine is very toxic to the surface of the eye,” he says. “In addition to oral treatment, the cornea can be gently debrided by rolling a cotton tip over the dendrite. That can debulk some of the active viral replicating bodies within the cells. They usually heal after the treatments discussed above, and they may or may not come back. But, once the virus is in you, it can always return.”

According to Chesterfield, Missouri, ophthalmologist Jay Pepose, patients who present with pure epithelial keratitis don’t typically suffer permanent vision loss. “In fact, it’s sometimes self-limiting even without treatment,” he says. “Before antivirals, many ophthalmologists just did debridement. In general, dendritic or geographic keratitis without stromal involvement are conditions where a topical antiviral is an appropriate therapy. In the United States, we have ganciclovir and trifluridine. Most people feel that ganciclovir is less toxic and more effective, so we usually start with topical ganciclovir five times a day, and then maybe we taper down to three times a day until the lesions resolve.”

Dr. Pepose believes that, even for patients with pure epithelial disease, it’s best to prescribe an oral antiviral. “If you see a lesion on the cornea, where is it coming from? It’s coming from the trigeminal ganglion,” he says. “If they recurrently reactivate, some of those cells are going to go lytic, and some of the ganglion cells will further establish a latent infection. Over time, the patient could lose enough of those sensory neurons that the eye would become desensitized, and he or she could wind up with a neurotrophic keratopathy. So, I think it’s important to shut down the infection at the source, and the only way to do that is with an oral antiviral. I usually use valacyclovir because it’s generic, it’s inexpensive and it’s effective.”

Another presentation of herpes simplex is dead viral particles on the cornea that elicit an immune response. “Our body finds them and starts reacting to them. So, it’s our own body that’s causing edema and opacity in the cornea,” Dr. Mah says. “The treatment for this is steroids, but steroids can reactivate epithelial disease, so you can actually get the epithelial disease by treating the stromal disease.1 We use a steroid with an antiviral, and the antiviral is for prophylaxis.”

The Herpetic Eye Disease Study II showed that the live virus and epithelial disease can be suppressed with oral acyclovir.2 “For people who have recurrent issues of live virus, we recommend oral antivirals indefinitely,” says Dr. Mah. “For people who have recurrent stromal keratitis, we recommend long-term steroid drops with either oral or topical antivirals to prophylax that.”

Dr. Jeng says stromal keratitis comes in two varieties: necrotizing; and immune-mediated non-necrotizing. “Necrotizing is where active virus is actually eating away at the cornea,” Dr. Jeng says. “Obviously, that would require high-dose treatment with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir. But, if it’s the more common immune-mediated herpes simplex stromal keratitis, where it’s mostly an inflammatory process, then the treatment is topical corticosteroids. I prefer to add oral antivirals, as there could be some viral activity stimulating the immune response, but the role of oral antivirals in these cases is really prophylaxis against having recurrences. Many years ago, HEDS demonstrated that, if you treat patients with a history of stromal keratitis with a low prophylactic dose of oral acyclovir (400 mg twice daily), their chance of experiencing a recurrence decreased by around 40 percent. Generally, I start these patients on antivirals, as well as topical steroids for stromal keratitis. After the inflammatory process is managed, I keep them on a prophylactic dose, because, when this heals, you can end up with some scarring that can decrease vision. Every time you experience a recurrence, there is a possibility for more scarring and decreased vision.”

Dr. Pepose agrees that herpes stromal keratitis can have visual consequences. “When HEDS was initiated in 1989, there was a lot of controversy about using steroids in patients with herpes,” he says. “Many people felt that corticosteroids could enhance the replication of the virus and cause more problems. So, HEDS decided to look at the role of steroids in patients with stromal keratitis. It really was a groundbreaking study in many ways. They came to the conclusion that patients who were given steroids did better. Seventy-three percent of the placebo arm failed, compared with 26 percent in the prednisone arm. This showed that there was a role for steroids. In fact, those patients were on steroids for 10 weeks and then they stopped. After 10 weeks, a lot of them lost the clinical gain. This showed us that you have to taper the steroid very gradually. Patients might need to be on low-dose steroids for a significant period of time, possibly months.”

Patients with ocular herpes can also develop endotheliitis. “This causes corneal swelling because endothelial cells become stunned and don’t work anymore,” Dr. Jeng notes. “It’s generally treated with both oral acyclovir as well as topical steroids for the inflammation.”

A rarer form of herpetic eye disease is disciform keratitis. These patients experience round, demarcated stromal and epithelial edema, and the formation of granulomatous keratic precipitates. “In the past, there was some debate about whether this condition is more of an anterior chamber inflammation or direct infection of endothelial cells,” says Dr. Pepose. “Many people feel that there’s probably some direct infection of corneal endothelium because the amount of inflammation is usually pretty sparse, and yet the amount of edema is pretty profound. These patients respond nicely to a tapered course of topical steroids. Then, there’s necrotizing keratitis, which means that there’s stromal involvement with ulcerations. These patients must be followed carefully because they can melt and perforate. It’s really important to try to get them to re-epithelialize as quickly as possible.”

Other rare presentations are herpetic retinitis, which is sometimes accompanied by herpes encephalitis, and there is acute retinal necrosis syndrome. “There are a variety of viral etiologies to that, including herpes zoster and herpes simplex,” Dr. Pepose adds. “All of those patients are treated systemically with oral or intravenous antivirals, and in some cases with adjunctive intravitreal injection of antiviral agents.”

Herpes Zoster

|

With varicella zoster virus, the shingles manifestation is most concerning, according to Dr. Mah. “People who get chicken pox are at risk for shingles. Shingles is the reactivation manifestation of the zoster virus,” he says. “Actually, the chicken pox vaccine that came out a couple of decades ago has caused a bit of an epidemic of shingles. The vaccine seems to offer protection against chicken pox in the young, but there seems to be an unintended increased risk of shingles in these folks. With the vaccine, people are also at risk for shingles at a younger age. When it affects the eye, patients can get issues ranging from glaucoma to neurotrophic keratitis to iritis. It’s very important to diagnose it early and start the patient on significant doses of oral antivirals. Antivirals should be prescribed for at least a week to try to prevent some of the long-term manifestations of the ocular issues of shingles.”

Dr. Mah explains the mechanism behind the post-shingles eye problems. “This virus can cause nerve damage and an immune reaction,” he says. “Very simplistically, the dead viral antigens are in the eye, and the immune system finds them and causes a reaction. It’s actually our own bodies causing the majority of the common issues post-shingles. [Management is typically steroids.] In this case, live virus usually does not come back unless there’s an issue with the immune system. Most people believe there is a benefit to long-term prophylaxis with zoster as well as simplex, but we don’t have that study yet.

“More questions surround zoster than simplex,” Dr. Mah continues. “Part of the reason is that we can’t grow the virus well, and we don’t have many animal models of the zoster virus. We have many animal models of the simplex virus, and we can grow it more easily, so it’s easier to study.”

Dr. Jeng agrees that herpes zoster is far more complicated than herpes simplex. Epithelial keratitis caused by herpes zoster manifests in two ways. “Sometimes, it’s just a mucous plaque, which doesn’t necessarily need to be treated with anything beyond lubrication,” Dr. Jeng explains. “If a patient gets a pseudo-dendrite, which has been shown to have active viral replication, then treatment is warranted. It can be treated either orally, which is my preference, or topically with ganciclovir. Trifluridine doesn’t work for zoster.”

Patients can also develop immune-mediated stromal keratitis. “Again, topicals don’t work, so it’s treated with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir,” Dr. Jeng says. “It’s important to note that zoster doses for treatment with these oral medications are double what they are for simplex. You can develop an endotheliitis and iritis with zoster, as well, and treatment is similar with steroids and acyclovir or valacyclovir.”

The question is whether there’s a rationale for using prophylactic treatment to prevent recurrences of zoster, as is done with herpes simplex. “Many people are doing this, but there’s no scientific evidence because the simplex and the zoster viruses are actually very different,” Dr. Jeng adds.

Dr. Jeng is the chair of the Zoster Eye Disease Study (ZEDS), a large study evaluating whether long-term prophylaxis with oral valacyclovir will decrease some of the corneal manifestations of zoster post-shingles.3

This double-masked, placebo-controlled, multicenter randomized clinical trial will test the hypothesis that suppressive antiviral treatment for 12 months with 1,000 mg daily of oral valacyclovir reduces the rate of new or worsening dendriform epithelial keratitis, stromal keratitis, endothelial keratitis, or iritis compared to placebo in patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus who have had an episode of one of these disease manifestations during the year prior to enrollment. It’ll also evaluate whether suppressive treatment reduces the severity and duration of postherpetic neuralgia. Patients in the study will be evaluated every three months for 18 months.

According to Dr. Jeng, vaccination is the best way to prevent herpes zoster. “The new vaccine is more than 90-percent effective, so if everyone were vaccinated, the number of cases would decrease,” he says “That would be first-line. But, short of everyone getting vaccinated—which we know isn’t going to happen—we hope that ZEDS will give us insights into how best to treat and prevent the anterior segment complications of HZO.” REVIEW

Dr. Pepose is a consultant to Glaxo Smith Kline. Dr. Mah is a consultant to Bausch + Lomb, Novartis, Allergan, and Kala. Dr. Jeng has no financial interest in any of the products mentioned.

1. Barron BA, Gee L, Hauck W, et al, for the Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Herpetic eye disease study: A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101:12:1871-1882.

2. Wilhelmus KR, Gee L, Hauck WW, et al, for the Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Herpetic eye disease study: A controlled trial of topical corticosteroids for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 1994;101:12:1883-1896.

3. Zoster Eye Disease Study. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03134196