Symptomatic vitreous opacities (SVO) or “floaters” are a common presenting symptom to ophthalmologists and can represent a significant challenge with respect to management. In many cases, patients will neuroadapt to the opacity and won’t need an intervention. In some instances, however, due to factors related to a patient’s personality or daily activities, the floaters can’t simply be ignored, and the physician must intervene. Here, we’ll outline how to evaluate these patients and discuss the possible interventions for symptomatic floaters.

Varieties of Floaters

In most cases, patients first become aware of floaters after the onset of a posterior vitreous detachment, but in many cases this visual disturbance develops due to the natural syneresis and condensing of vitreous proteins that were previously optically clear. Additionally, patients can develop SVOs during and after the onset of intraocular inflammation or hemorrhage, which can become particularly visually disruptive and prompt evaluation from patients seeking relief. In the majority of cases, especially when it’s the result of a PVD, patients can be safely observed; after several months the symptoms become less bothersome as a result of either the natural migration of the SVO out of the visual axis or, more commonly, the neuroadaptation of the brain, resulting in “ignoring” the visual disturbance. This makes sense in the case of a PVD as it is acute in onset and not likely to progress.

In contrast, in the case of SVOs from vitreous syneresis, the onset is gradual and may be progressive. Additionally, the vitreous in these cases may be relatively “fixed,” making it less likely to migrate out of the visual axis. Neuroadaptation may occur in these instances, however some patients with certain personality traits, psychological disorders or those who require frequent or high levels of fine vision to perform hobbies or jobs may be unable to ignore their floaters and subsequently seek evaluation and treatment.

|

| Figure 1. A 54-year-old male patient with prior pars plana vitrectomy for symptomatic floaters presenting with an acute PVD. Temporal laser from prior surgery is visible. The patient at that time didn’t have any retinal tears or detachments. |

Assessing the Patient

Prior to considering surgical or procedural intervention, a thorough evaluation of the patient’s subjective and objective findings is warranted.

Although in most cases the onset of symptomatic floaters is due to the natural history of vitreous syneresis or the onset of a PVD, clinicians should always be vigilant and rule out secondary etiologies which may require more urgent intervention or further work up. These include vitreous hemorrhage from neovascular pathology, intraocular inflammation from a non-infectious or infectious uveitis, and even rhegmatogenous pathology which may be obscured by hemorrhage or significant pigment dispersion. Ask patients about a history of uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension, previous or ongoing pain, eye redness, or photophobia. Occasionally, they may even carry a diagnosis of prior uveitis.

In the older patient with trace to 1+ vitreous cell that is worsening, the clinician should also consider masqueraders of uveitis such as primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. If suspected, thoroughly investigate these etiologies prior to considering primary treatment of floaters.

In the case of non-pathologic or typical floaters, patients often complain of intermittent blurred vision, difficulty concentrating during tasks which require increased and prolonged visual attention, and overall distress. They may specifically report a moving “smudge” or haze in their vision despite testing 20/20 with correction in the affected eye. The ophthalmologist should inquire about specific hindrances to activities of daily living. Do the floaters impact productivity at work and, if so, by how much? Are they only able to read or watch television for a certain length of time before becoming too distracted? Are they engaging less in sports and hobbies that they previously enjoyed, and can that reduction be quantified? The more specific and measurable the impairment, the better both the treating ophthalmologist and patient can establish a functional baseline and track changes over time.

Another option to more systematically assess these subjective complaints is to employ the use of questionnaires like the National Eye Institute’s Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ)-25 or even a personalized survey designed by the clinician. This can be done while in the waiting room prior to seeing the physician. These surveys ask questions similar to those posed above but can be scored in a standardized manner and again be used as a quantifiable measure for patient and clinician to gauge the extent of the impairment. They may also allow the patient to more thoroughly explore their experience and make an informed decision about surgical intervention vs. observation.

Regardless of the method employed to fully evaluate subjective complaints, these findings should be carefully documented during an initial visit and then updated at follow-up examinations. The duration of these symptoms is critical, with most surgeons opting to observe for at least three to six months from the onset of bothersome floaters before considering intervention.

Assessing a patient’s objective findings can be particularly difficult, as there is often a mismatch between typical examination measures and the patient’s level of distress. It’s not uncommon for these patients to present with 20/20 best-corrected visual acuity and barely noticeable changes in the vitreous cavity. While there is no “typical” patient who presents with floaters, they frequently present after PVD, may have moderate to high myopia, and may be phakic or pseudophakic. On examination, there is a notable absence of cell or pigment in the vitreous cavity and a vitreous condensation over the optic nerve. With oblique illumination of the vitreous, the extent of condensations in the vitreous can be appreciated.

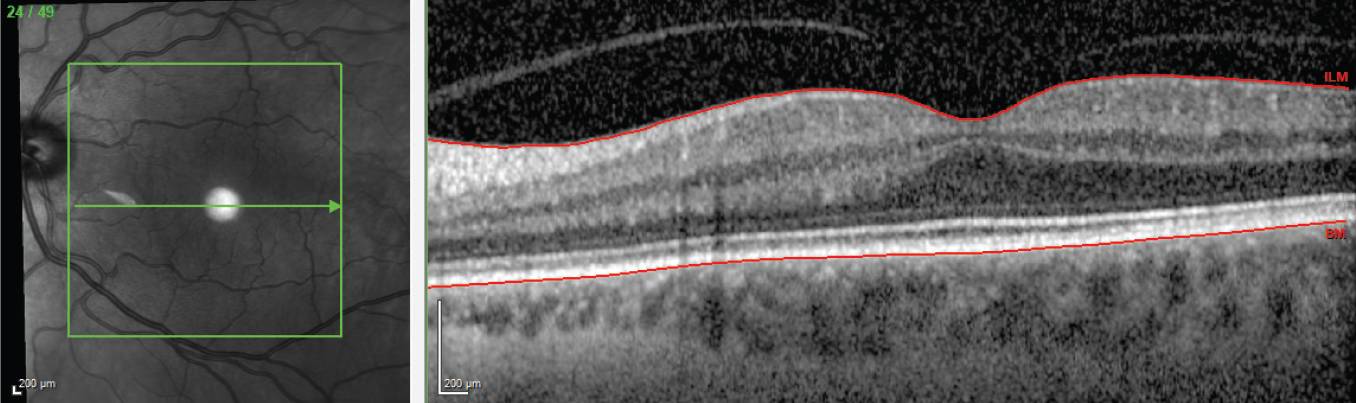

|

| Figure 2. OCT of the contralateral macula that underwent prior PPV for removal of visually disruptive floaters, demonstrating that the posterior hyaloid is firmly adherent to the retinal surface. |

However, without keen examination, the exam may certainly appear unimpressive, making it difficult to decide whether to intervene. There are, however, a few strategies that go beyond the standard eye assessment that may be helpful in bolstering or discouraging a decision to pursue intervention.

Degradation in contrast sensitivity testing has been shown to correlate with floater-related visual impairment and improvement after intervention. This measurement can therefore be used to stratify patients initially for documentation purposes. Additionally, the actual size and location of the floaters can be visualized with optical coherence tomography or ultrasound. In many cases, the floater that’s the source of impairment is easily seen on these imaging modalities, which provides another data point to support intervention. On OCT, using the en face NIR image in video format to look for visual opacities that are creating shadowing on the macula can help you understand what the patient may be experiencing. Despite having these additional tools to objectively document a patient’s floater “burden,” the patient’s complaints may be out of proportion to any contrast sensitivity or imaging findings; therefore, appropriate justification for intervention will rely on careful evaluation of subjective data and clear patient understanding of the risks and benefits of each intervention.

Considerations Before Treatment

Once a patient’s subjective and objective data have been carefully reviewed and his symptoms have been deemed to be persistent and disruptive to activities of daily living, you can pursue a course of intervention. Options include pars plana vitrectomy and YAG vitreolysis. The benefits of PPV dramatically surpass the benefits of YAG vitreolysis, based on currently available studies, and thus we prefer the use of PPV for the treatment of visually disruptive floaters. (We’ll present an overview of the literature for YAG laser for vitreous floaters at the end of this article.)

As with all surgical intervention, both you and your patient should perform a careful review of the benefits and risks. This is especially true in the case of PPV for SVOs because this condition isn’t vision-threatening, unlike almost all other indications for retinal surgery, such as retinal detachment, macular hole and progressive epiretinal membrane. Fortunately, the benefits of surgery with respect to symptomatic improvement are significant and supported by several studies.

The first study, published in 2000 by William Schiff, MD, and co-workers,1 found significant benefits in quality-of-life measures using the VFQ-39 questionnaire, specifically in the areas of general vision, near vision and distance activities. In this study the average age was approximately 60 and all patients were pseudophakic or aphakic, and 20-gauge surgery was performed. In another more recent study,2 approximately 80 percent of the patients had PVD, about 85 percent of them were phakic and surgeons performed 25-gauge surgery. This study found a similar high degree of improvement in pre- and postoperative VFQ survey results. Studies3,4 that used surveys to assess patient perceptions of overall surgical success have found that between 88 and 96 percent of patients report overall satisfaction with PPV, again demonstrating the high degree of efficacy with this intervention. Other reported benefits include an improvement in maximum reading speed5 and a normalization of contrast sensitivity degradation after vitrectomy.2

Although the benefits of PPV for SVOs are well documented, the clinician should carefully review the risks with the patient, particularly those risks that are unique to this specific context. In general, vitrectomy surgery carries several standard risks, which include:

- cataract formation in phakic patients;

- retinal detachment;

- postoperative hypotony (from leaking sclerotomies);

- suprachoroidal hemorrhage;

- endophthalmitis;

- formation of macular hole or epiretinal membrane; and

- postoperative cystoid macular edema.

Fortunately, many of these risks are rare in the modern era. However, there are a few risks worth discussing in greater detail.

• Risk of cataract. One study reported a 60-percent need for cataract surgery within 21 months after PPV for floaters.4 Some studies report lower rates of cataract surgery, with one2 reporting only 16.9 percent at 13.1 months. As retina surgeons, however, we recognize there’s a time-dependent progression to cataract development and the risk is nearly 100 percent if the time after PPV is extended long enough. As such, the authors prefer to render patients above 50 years of age pseudophakic prior to proceeding with PPV for visually disruptive floaters. Occasionally, removing the cataract alone improves the patient’s symptoms and PPV may be deferred.

Phakic patients electing for PPV should fully understand that they’ll require additional surgery to remove their inevitable cataract. For those younger than 50 (fortunately a rare event when considering this type of surgery), the patient should understand the implications of losing accommodative capacity.

• Risk of retinal tear. With respect to retinal tear and detachment risk, one study6 of 116 consecutive PPVs for SVOs reported an iatrogenic intraoperative retinal break risk of 16.4 percent and a retinal detachment rate of 2.5 percent, which is similar to PPV for other indications. Some studies reported a rate as low as zero2,5 for postoperative retinal detachment while others had rates as high as 10.9 percent.7

The wide range of iatrogenic tears reported is certainly very concerning, and it is worthwhile to consider that many of these studies did not report the status of the posterior hyaloid. Extrapolating from epiretinal membrane cases (hyaloid typically elevated) and macular hole cases (hyaloid typically down), the rates of retinal tear and detachment are considerably higher in the macular hole cases. This is intuitive, as all retinal surgeons know that hyaloid elevation, by the nature of the maneuver, puts traction on the anterior retina and can result in iatrogenic tears.

The surgeon must consider the differential risk profile for surgery in patients with and without PVD when approaching this surgery. It’s our bias that this surgery should be performed overwhelmingly in patients’ who have a preexisting and chronic PVD (four to six months) as defined by a true Weiss ring on clinical examination.

One exception to this rule involves patients with visually disruptive floaters from asteroid hyalosis. While it’s not clearly understood why many are asymptomatic and a few are highly symptomatic, it’s worthwhile to note that these patients typically don’t have a PVD, even when there appear to be vitreous condensations over the nerve.8 Additionally, the vitreoretinal adhesions are quite strong, making PVD induction in these cases challenging. Perform hyaloid elevation very judiciously, staying tangential to the retinal surface when propagating the posterior hyaloid elevation anteriorly.

Also, if the hyaloid is down in these cases, attempt hyaloid elevation in order to lower the risk of a late retinal tear and detachment from subsequent spontaneous PVD development.

• Endophthalmitis. Despite small-gauge, uneventful surgery and excellent preoperative Betadine cleaning of the eye, this general risk of vitrectomy remains, with a rate of 1/1,730, according to a large, prospective study.9 This study found no difference in rates between small (25 or 27) vs. large (20) gauge surgery. Despite the low risk, the severe visual loss potential from this complication ought to be discussed with the patient as part of the informed consent prior to proceeding with surgery.

|

| Figure 3. Postoperative photo with intraocular gas bubble following retinal detachment repair. |

A Cautionary Case

To illustrate the long-term risks of PPV for SVOs, we present a patient who underwent sequential, bilateral vitrectomy for symptomatic floaters while in his 30s and presented with a unilateral macula-on retinal detachment after the development of a PVD (at 51 years of age). At the time of his initial PPV, the posterior hyaloid wasn’t elevated and temporal laser was applied in the right eye (Figure 1). Examination demonstrated a Weiss ring over the optic nerve (confirming that the hyaloid wasn’t removed at the prior surgery). Also, in the contralateral eye, the posterior hyaloid by OCT remained attached (Figure 2). Subsequently, a retinal tear occurred at the posterior margin of the laser treatment area, which likely occurred at the time of acute PVD and progressed to retinal detachment. The patient underwent uneventful PPV, endolaser and SF6 gas for the repair of his retinal detachment (Figure 3). This case highlights that management of the posterior hyaloid is critical when considering PPV for visually disruptive floaters. When PVD induction isn’t performed (which we don’t recommend), be sure to inform patients prior to surgery that the risk of RD remains even decades into the future.

YAG Vitreolysis

Although we don’t use this method in our practice, YAG vitreolysis for SVOs is a non-surgical intervention which may be a reasonable option for some patients. While inherently less invasive, the benefits of YAG laser with respect to patient symptom improvement aren’t as robust as PPV. One study10 that compared YAG laser to vitrectomy reported significant relief (defined as 50 to 70 percent improvement) in only 2.5 percent of YAG cases, while 93.3 percent of vitrectomy patients reported complete symptom resolution. Overall moderate relief (30 to 50 percent improvement) was reported in about one-third of the YAG laser patients. Another study11 that compared YAG laser to sham treatment reported a 54-percent rate of symptomatic relief. In this study, only patients with a solitary Weiss ring were included, and the ring was specifically targeted, which may explain why the symptomatic improvement was higher than in other studies.

Regarding the YAG procedure for floaters, it’s worth mentioning that significantly more shots (sometimes greater than 100) and higher amounts of energy are required to completely vaporize the vitreous opacity as compared to that required to perform a posterior capsulotomy.

Given the modest reported benefits, the risks of YAG laser should be mentioned. One reported advantage to YAG laser is the avoidance of cataract progression inherent to PPV. However, there have been cases of crystalline lens or posterior capsular damage from the laser which led to rapid cataract formation and the subsequent need for surgery,12 which is often more complicated. Additionally, cases of retinal tears or detachment, retinal hemorrhage and prolonged elevated intraocular pressure have also been reported with this procedure.13,14

Given the only moderate reported symptomatic benefit and fairly serious but rare potential complications, we believe this procedure should be reserved for patients who aren’t good candidates for surgery and/or those that have a specific area in the vitreous that can be directly targeted, such as a Weiss ring. It’s best if this vitreous opacity is also located in an area that can be correlated reliably with a patient’s specific symptoms.

In conclusion, symptomatic floaters present a unique challenge to ophthalmologists with respect to management. Patients may complain of visual impairment despite having excellent visual acuity and otherwise healthy eyes. Understandably, this leads to hesitation on the part of treating physicians as to whether the risks of intervention are justifiable. As with most providers, we believe that all patients with visually disruptive floaters should be followed over a period of several months and multiple office visits to ensure a full understanding regarding the risks of intervention, and to allow time for the adaptation that occurs in the vast majority of cases.

When deciding to intervene, surgeons should discuss the specific risks, including cataract formation—which will require subsequent surgery—and the risks of retinal tears or detachments. Our practice is to selectively consider this surgery in patients with a chronic PVD, and to discourage patients from considering this surgery in the absence of the PVD (with the exception being symptomatic asteroid hyalosis patients). The authors always check for PVD at the time of surgery and if one is not present (as can occur in cases of myopic vitreoschisis), we induce a PVD and look carefully for iatrogenic tears.

Ultimately, we believe this surgery offers relief to carefully selected patients who have visually disruptive symptoms. However, the patient must fully understand the risks of the surgery prior to proceeding.

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Naguib is a clinical instructor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Dr. Modi is an associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and director of NYU’s tele-retina program.

1. Schiff WM, Chang S, Mandava N, Barile GR. Pars plana vitrectomy for persistent, visually significant vitreous opacities. Retina 2000;20:591–596.

2. Sebag J, Yee KMP, Nguyen JH, Nguyen-Cuu J. Long-term safety and efficacy of limited vitrectomy for vision degrading vitreopathy resulting from vitreous floaters. Ophthalmol Retina 2018;2:881–887.

3. Schulz-Key S, Carlsson JO, Crafoord S. Long-term follow-up of pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous floaters: Complications, outcomes and patient satisfaction. Acta Ophthalmol 2011;89:159–165.

4. Mason JO, Neimkin MG, Mason JO, et al. Safety, efficacy, and quality of life following sutureless vitrectomy for symptomatic vitreous floaters. Retina 2014;34:1055–1061.

5. Ryan EH, Lam LA, Pulido CM, et al. Reading speed as an objective measure of improvement following vitrectomy for symptomatic vitreous opacities. Ophthal Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2020;51:456–466.

6. Tan HS, Mura M, Lesnik Oberstein SY, Bijl HM. Safety of vitrectomy for floaters. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:6:995-8.

7. deNie KF, Crama N, Tilanus MAD. Pars plana vitrectomy for disturbing primary vitreous floaters: Clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013;251:1373–1382.

8. Mochizuki Y, Hata Y, Kita T, Kohno R, Hasegawa Y, Kawahara S, Arita R, Ishibashi T. Anatomical findings of vitreoretinal interface in eyes with asteroid hyalosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009;247:9:1173-7.

9. Park JC, Ramasamy B, Shaw S, Prasad S, Ling RH. A prospective and nationwide study investigating endophthalmitis following pars plana vitrectomy: Incidence and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:4:529-33.

10. Delaney YM, Oyinloye A, Benjamin L. Nd:YAG vitreolysis and pars plana vitrectomy: Surgical treatment for vitreous floaters. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:21–26

11. Shah CP, Heier JS. YAG laser vitreolysis vs sham YAG vitreolysis for symptomatic vitreous floaters: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:918–923.

12. Sun I-T, Lee T-H, Chen C-H. Rapid cataract progression after Nd:YAG vitreolysis for floaters: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Ophthalmol 2017; 8:321–325.

13. Hahn P, Schneider EW, Tabandeh H, et al. American Society of Retina Specialists Research and Safety in Therapeutics (ASRS ReST) Committee. Reported complications following laser vitreolysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:973–976.

14. Cowan LA, Khine KT, Chopra V, et al. Refractory open-angle glaucoma after neodymium-yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser lysis of vitreous floaters. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:138–143.