|

Surgeons say debriding a 0.5- to 1-mm ring around the interface can give flaps a chance to adhere and prevent ingrowth. |

Case-study Pearls

Surgeons say you can take different tacks depending on such factors as whether the trauma recently occurred or occurred further in the past, as well as whether the cornea is torn or not and the extent of epithelial ingrowth in the interface.

• The intact flap. York, Pa., surgeon Denise Visco encountered a patient, 10 years postop after her LASIK, who had bent over her tomato garden and ran her eye into a plant stake. “She immediately had pain, loss of vision and foreign body sensation,” Dr. Visco recalls. “Since I wasn’t in the office that day, she saw my optometrist, who did nothing to it, including touching the flap. The next day someone else saw her, but still didn’t touch the flap. I informed the eye-care providers that they have to touch the flap to properly examine it, which I promptly did with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator, and saw that it moved. In the short, six-hour period between the injury and her first visit to our office, the epithelium had already begun to grow into the interface. Then, between that visit and the second one at which I saw her, she was actually 50-percent re-epithelialized underneath the flap on the corneal bed.”

In such a case, Dr. Visco says it’s helpful to put the patient under the laser microscope and thoroughly debride everything. “I didn’t use any alcohol or mitomycin, but I made sure I removed all of the epithelium on the base of the flap,” she says. “I also scraped the epithelium off of the underside of the flap. I removed any epithelium that looked thick and loose, even on top of the flap. Then, I went around the edge of the flap and removed approximately 0.5 to 1 mm of epithelium around the edge of the ocular side of the flap. I think removing the epithelium from around the edge like this gives the flap a head start for adhering; it creates a delay before it reaches the edge of the flap. The stronger the bond between the flap and the bed, the less chance the epithelium can slip under.”

After that, Dr. Visco had to deal with another common issue with flap trauma: striae. “When I went to put the flap back down, it had folds and wasn’t very adherent to the bed,” she says. “In response, I used a trick that I had learned years ago from a colleague: Create a mixture that’s 50 percent BSS and 50 percent water and instill it onto the eye. As the flap absorbs the mixture, it will swell and some of the wrinkles will disappear. Also, it makes the tissue surfaces of the flap and the bed more tacky, so the flap will adhere to the bed better. I then let the flap dry for about five minutes, placed a bandage contact lens and watched it daily. The patient was lucky: She went from counting fingers at presentation to hand motions/CF after I finished my intervention. After two weeks she saw 20/50 and had no epithelial ingrowth, and, after a year, she now sees 20/20.”

The medications during that postop period are important, and surgeons say they’re similar to a postop LASIK medication regimen, but more intense. “I treated her with Zymaxid antibiotics, topical steroids, Pred Forte q1h, and Medrol dose packs with a double taper,” Dr. Visco explains. “I also gave her some gabapentin for discomfort. I wanted her on more oral steroid than just a single pack, so I kept the dose the same but doubled the time. So, instead of taking six doses on day one, five on day two, et cetera, she took six doses on day one, six on day two, five on day three, five on day four and so on. It’s easier to do this than to give the patient a big bottle of 5 or 10 mg pills and say, ‘Take six for four days, five for four days, et cetera.’ ”

|

Infection is always a worry with trauma involving foreign bodies. |

Greensboro, N.C., surgeon Karl Stonecipher agrees that choice of post-repair medicine is important in these patients. “For antibiotics, I prefer vancomycin because it covers the majority of staph species, and I’ll use Polytrim or gentamicin because it will usually make up the difference for me in my neck of the woods,” he says. “I wouldn’t fault anyone if they used a fluoroquinolone, though. I wouldn’t use an antibiotic that has a lot of mucoadhesives, however, because if it’s too sticky it can be challenging to work with when a contact lens is in place. If the patient has an injury from an organic cause, such as a branch or bush, I would also strongly consider putting him on the antifungal natamycin in addition to the antibiotic. In terms of steroids, I’ll use a long-term steroid, probably with a month taper. In many cases I’ll use Pred Forte rather than Durezol because of the latter’s mucoadhesives, but if the flap is ripped off and it’s bare sclera I’ll typically use Durezol. I’ll also watch the patient’s pressure for pressure-induced stromal keratitis. Note that it can be challenging measuring pressures in these post-flap trauma cases, and you can’t measure it early on because you have them in a contact lens.”

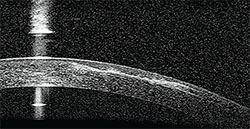

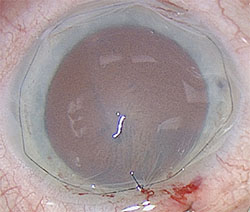

• The torn flap. The situation changes when the patient’s flap is torn by the trauma, surgeons say. This was the type of scenario faced by Bradenton, Fla., surgeon Cathleen McCabe when a 60-year-old patient, who had undergone LASIK monovision 10 years prior, had a trauma similar to Dr. Visco’s: Three months before seeing Dr. McCabe, the patient was gardening and suffered an injury to her left eye from a steel rod. Unlike Dr. Visco’s case, however, this patient had developed an infection in the injured eye, which healed after antibiotic treatment but which the patient said left a “wrinkle in the cornea.” The vision in the left eye, which had been left a little myopic by the monovision LASIK, was 20/50 uncorrected, and 20/20-1 with correction. Upon examination, Dr. McCabe saw that the left eye’s flap was torn, and there was epithelial ingrowth, fixed folds and anterior stromal scarring. “I consulted with colleagues, and was considering lifting the flap to remove the epithelium to see if the flap was salvageable,” says Dr. McCabe. “However, it didn’t look like it was. One of the tools I used that I found very helpful was anterior segment OCT. With it, I could see the disrupted corneal flap and that the scarring went deeper than the flap; it didn’t look salvageable on OCT.” (See image, above.)

|

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography showed that this patient’s scar went deeper than just the level of the flap. |

While considering her options, one of the surgeons Dr. McCabe spoke to was William Wiley, MD, of Cleveland, Ohio. He told her about a patient with persistent epithelial ingrowth beneath his flap in which Dr. Wiley amputated the flap and then did a series of ORA intraoperative aberrometry readings to get the residual refractive error. “Dr. Wiley took an ORA reading pre-flap lift, then another through a bandage contact lens pre-lift,” Dr. McCabe recalls. “He then lifted the flap and took readings with and without the bandage contact lens to see if he could get a better reading with the contact lens in place and also to determine what the effect of the contact lens was. He then amputated the flap and performed an excimer PRK at 60 percent of the ORA refractive-error reading, and the patient did well.” Dr. McCabe says that most surgeons, though, will manage the ingrowth and flap issues as best they can, then wait for refractive stability before performing any refractive procedure. Many surgeons will use adjunctive mitomycin-C.

In Dr. McCabe’s case, the patient actually moved away to Michigan; a surgeon there amputated the flap, sutured amniotic membrane over the area and waited for it to heal. Now, the patient sees 20/25 uncorrected.

Dr. Stonecipher says that flap removal is a more viable option these days than in the early days of LASIK. “In many late flap traumas, a referring surgeon will have already tried to repair them,” he says. “I’ve had trauma cases referred to me after they’ve tried to suture the flap down but it’s got epithelial ingrowth and melting of the flap edges. When I was dealing with such a case years ago, Jack Holladay told me to just take the flap off. I objected, thinking the patient would be +10 D, but Dr. Holladay said that if it was a femtosecond flap, it most likely will be all right. It turns out that the older,

|

Amputating the damaged flap and sewing on amniotic membrane can help eyes recover from trauma. |

Dr. Stonecipher consults for Alcon, Allergan and B + L. Dr. McCabe consults for Alcon. Dr. Visco has no financial interest in the products discussed.