What if we told you there was something you could do in your office that could actually catch one of the most missed diagnoses in ophthalmology, prevent disease progression and save vision? What’s more, the instruments you need to do it are likely in your exam lane right now. The trick, however, is you actually have to use them. The exam, of course, is gonioscopy, and it’s surprisingly underutilized.

Here, we’ll help you overcome your hesitancy to “go gonio” by sharing our best tips and techniques for performing the exam.

The What

Before embarking on a discussion of our techniques, it helps to review the disease process.

|

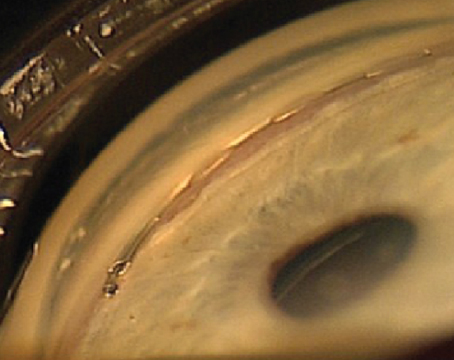

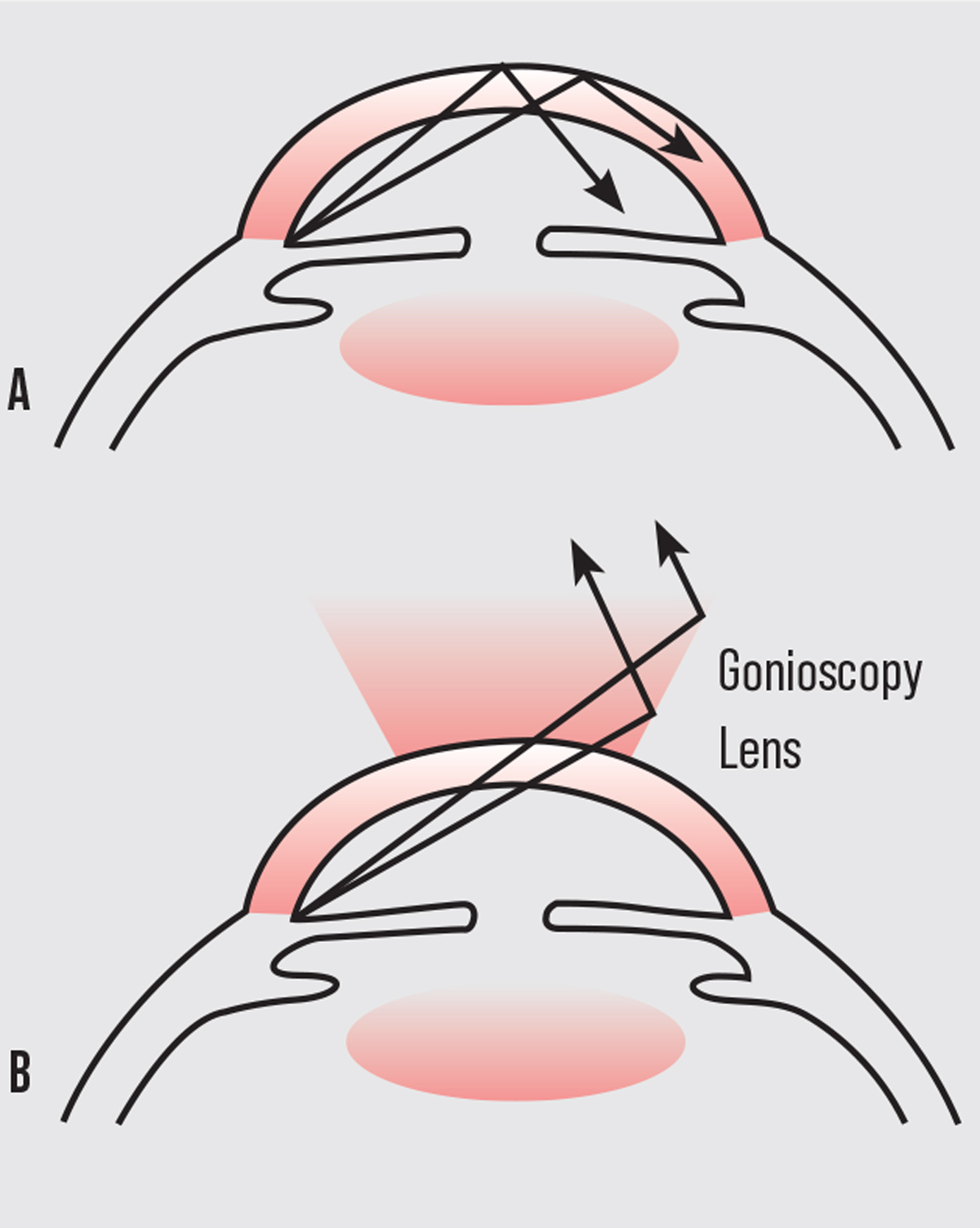

| Figure 1. A: Total internal reflection of the light rays. B: Overcoming total internal reflection by creating a new lens-cornea interface. |

The term “narrow angle” refers to an anatomical condition whereby the iris blocks the trabecular meshwork (irido-trabecular apposition), which obstructs the aqueous humor outflow pathway. This causes increased intraocular pressure leading to optic nerve damage and irreversible vision loss through angle-closure glaucoma. By looking at the drainage angle through gonioscopy physicians can determine not only if the angle is open or closed, but also if there are abnormal blood vessels, excessive pigment, masses or foreign bodies, adhesions (synechiae) or damage from previous ocular trauma. Unfortunately, direct visualization of the angle structures isn’t possible, since light from the anterior chamber angle strikes the air-tear interface at an angle greater than 46 degrees (critical angle) and is thus totally reflected back into the eye (total internal reflection). Fortunately, with the placement of a contact gonioscopy lens, the air-cornea interface is modified. This allows light to strike the cornea at an angle steeper than the critical angle, bypassing total internal reflection, thereby allowing the observer to visualize individual angle structures.

The Who

The fact of the matter is that we’re doing far fewer gonioscopy exams than should be routinely done based on the standards set forth by the AAO. In fact, the 2006 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Part B Extract Summary System data revealed a gonioscopy utilization rate for ophthalmologists of just 3 percent, meaning that for every 100 ocular examinations paid for by Medicare to ophthalmologists, there were only three paid claims for gonioscopy.1 Studies have shown that less than half of patients who were diagnosed with glaucoma had a gonioscopy done during their initial evaluation despite carrying the diagnosis of glaucoma.2 Whether it’s due to the time constraints of a busy clinical day or lack of comfort with performing accurate gonioscopy, this particular type of exam is often relegated to being a “next visit problem.” In other instances, it’s simply forgotten about. And thus, chronic angle-closure glaucoma is one of the most frequently missed glaucoma diagnoses.

Since chronic angle closure can behave like open-angle glaucoma in its early stages, gonioscopy becomes an afterthought. In fact, one study showed that for patients who suffered an acute angle closure attack, less than a third of them had a gonioscopic evaluation as part of their routine ophthalmic examination in the prior two years.3

Similarly, in a talk given at the ASCRS annual meeting in 2014, Devesh K. Varma, MD, of the University of Toronto recounted that, out of 1,234 glaucoma referrals from ophthalmologists, only 179 included angle status and 8.9 percent had missed angle-closure glaucoma.4 And, while the Van Herick method may be a quicker and technically less challenging way to assess the angle, according to a retrospective study, male sex (odds ratio, 2.22; p<0.001), myopia (odds ratio, 1.4; p=0.048), and Black (odds ratio, 4.11; p<0.001) and Asian (odds ratio, 2.24; p=0.044) race are at increased risk of being inappropriately diagnosed as having a deep angle, when they are, in fact, narrow on gonioscopy.5 In fact, in a review of all glaucoma malpractice litigations against ophthalmologists in the United States between 1930 and 2014, 18.5 percent of cases related specifically to a failure to diagnose or a mismanagement of angle-closure glaucoma.6

While narrow-angle glaucoma is less common than open-angle glaucoma, a large number of population-based studies have shown that people who have angle-closure glaucoma typically have more severe optic nerve damage as well as a greater and earlier risk of irreversible blindness. A recent meta-analysis found that the current estimated population of primary angle-closure glaucoma worldwide is over 17 million, a number estimated to increase to 26 million by 2050.7 The burden of blindness from angle closure is especially high in Asian countries. Other individuals at higher risk for narrow angles include females, hyperopes, those with a family history of it and individuals above the age of 40. Bottom line: We should be gonio-ing everybody!

|

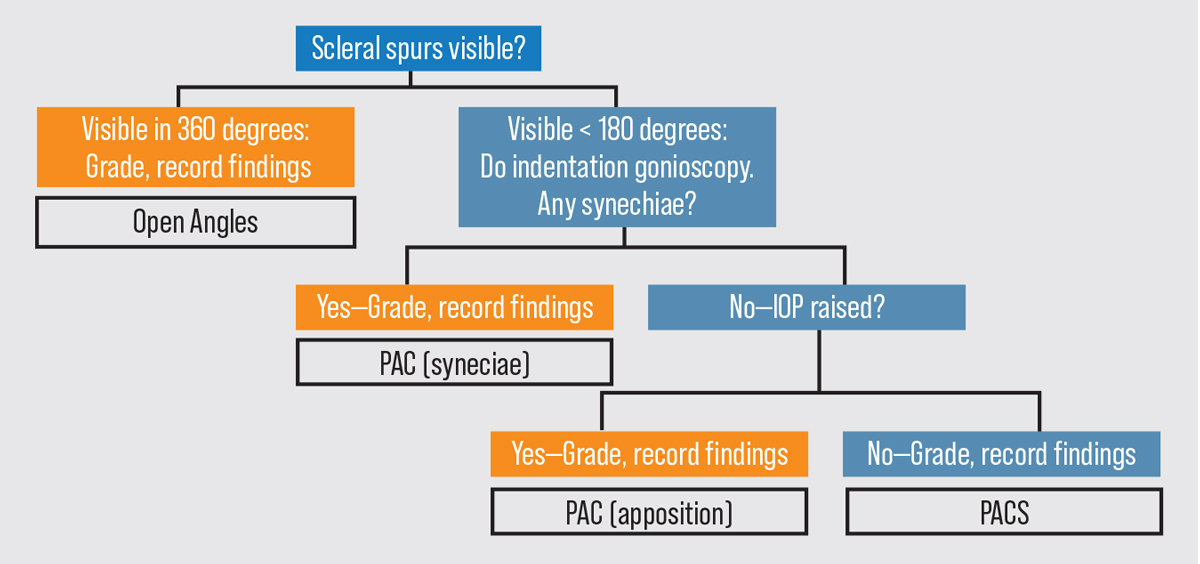

|

Figure 2. A gonioscopy flowchart for use when evaluating a patient. Click image to enlarge. Abbreviations: PAC (primary angle closure); PACS (primary angle closure suspect). Photo: Asia Pacific Glaucoma Guidelines 2016. |

The When

The AAO’s Preferred Practice Patterns suggests that gonioscopy should be repeated periodically, preferably every one to five years.1

We typically recommend gonioscopy be performed every three to four years for established patients. Serial gonioscopy is important since characteristics of the angle can change as patients age and develop other ocular conditions such as cataracts, pseudoexfoliation, or inflammatory conditions such as uveitis. Of course, every new patient should have a gonioscopic evaluation as part of their initial comprehensive examination. And while we trust our referring colleagues, we believe it’s important that each clinician takes the time to perform his or her own gonioscopy to avoid inter-grader variability in angle assessment.

The Where

Clinic conditions are important when performing accurate gonioscopy.

First and foremost, the patient must be comfortable. Ensure that the patient’s forehead is against the bar and lateral canthus is lined up to the markings on the slit lamp in order to minimize movement and readjustment during examination. Patients should be instructed that a small contact lens will be placed on the eye, and that while they may feel a light pressure, they won’t feel any pain. It’s often helpful to show them the lens prior to placement so that they know what to expect. It’s also crucial to stress that they keep both eyes open throughout the exam.

It’s also important that gonioscopy be performed in a dark room if possible, which can be difficult considering the amount of light emitting from the computer screens in a standard clinical office room. Not only can ambient light generate more glare, but it can also cause pupillary changes and artificially open the iridocorneal angle. Creating ideal working conditions can be especially difficult during the acute evaluation of the angle in emergency-room settings, which can happen when a patient comes in for suspected angle closure or neovascular glaucoma. In these cases, it’s still a worthwhile endeavor to at least attempt a gonioscopic examination of both eyes as best as you can.

|

The Why

Identification of a narrow angle is necessary to reduce the burden of blindness from angle-closure glaucoma.

If you place the gonioscopic lens on the cornea and the trabecular meshwork isn’t visible, this indicates a narrow or closed angle. The iridotrabecular contact can be due to permanent causes such as peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) or dynamic appositional closure. For this reason, it’s important to perform indentation gonioscopy on all patients. By doing indentation gonioscopy, you can determine the degree of synechial closure versus appositional closure in each of the four quadrants. In this technique, you apply pressure to the cornea with the lens, which pushes aqueous into the anterior chamber angle and causes it to open. If there’s synechial closure, the angle may not open with this application of pressure. Distinguishing the type of closure as well as differentiating PAS from fine iris processes (which are small extensions of the iris that insert onto the scleral spur) are crucial, as the former physically impedes aqueous outflow and the latter can be overcome with indentation.

The type of angle closure guides management. For example, in cases of secondary angle closure, such as in neovascular glaucoma, a high degree of synechial closure portends earlier shunt surgery, since topical and even oral medications can be insufficient to lower elevated IOP. A more commonly encountered clinical scenario is one in which a patient is found to have at least two quadrants where only the trabecular meshwork is visible. For these high-risk appositional anatomical narrow angles, laser peripheral iridotomy are considered an appropriate first-line intervention. LPIs are fairly benign laser procedures, taking less than five minutes to do, that can potentially prevent the devastating threat of blindness in patients who are considered angle-closure suspects.

There’s is an ongoing debate, however, as to whether or not we’re overtreating narrow angles with LPIs. The ZAP study showed us that you need to treat 44 primary angle closure suspect patients in order to prevent one case of primary angle closure over a time period of six years, suggesting that we may be better off just watching our suspect patients with serial gonioscopy. Of course, this necessitates us diligently performing gonioscopy on our patients routinely, which, as we have already established, we’re doing a very poor job of.

|

| Figure 4. Anterior chamber angle classification systems. Click image to enlarge. |

… And, Importantly, the How

Once the room lights are turned off, the undilated patient should be seated comfortably at the slit lamp with the forehead against the headband and the chin on the chinrest. You should be just as stable and comfortable, with your elbow resting on either the slit lamp table or a cushion for support. Next, administer a drop of anesthetic. Then, with most gonio lenses, you have to apply a coupling agent such as GenTeal Gel (carbomer 0.22% and hypromellose 0.3%; Novartis). Don’t apply too much of the coupling fluid (about half the lens) as the fluid won’t stay on the lens by the time the lens is placed on the eye. Then, gently place a gonio lens with a flat base curve (41 D) onto the anesthetized cornea. It’s helpful to first ask the patient to look all the way up as you slide the bottom of the lens into the inferior fornix. This should be done quickly as not to lose too much of the coupling solution. Once the gonio lens is stabilized, ask the patient to look straight into the central mirror. A seal forms when the lens is pressed gently forward.

Minimize the beam to a width of about 2 to 3 mm, and offset it about 30 degrees. Set the magnification to 10x or 25x. Take care not to shine the beam directly into the pupil. Move the slit lamp back and forth until you can clearly visualize the iris. The key to correctly interpreting and recording your view is to always perform the procedure in the same manner so you have consistent results. We find that it’s often easiest to start at the inferior angle and subsequently move clockwise. The inferior angle is the widest and often the most heavily pigmented angle. However, in some cases of acute angle closure, the pigment may be denser superiorly due to the increased apposition of the iris against the trabecular meshwork. It’s important to remember that your mirror is 180 degrees away from the angle you are viewing.

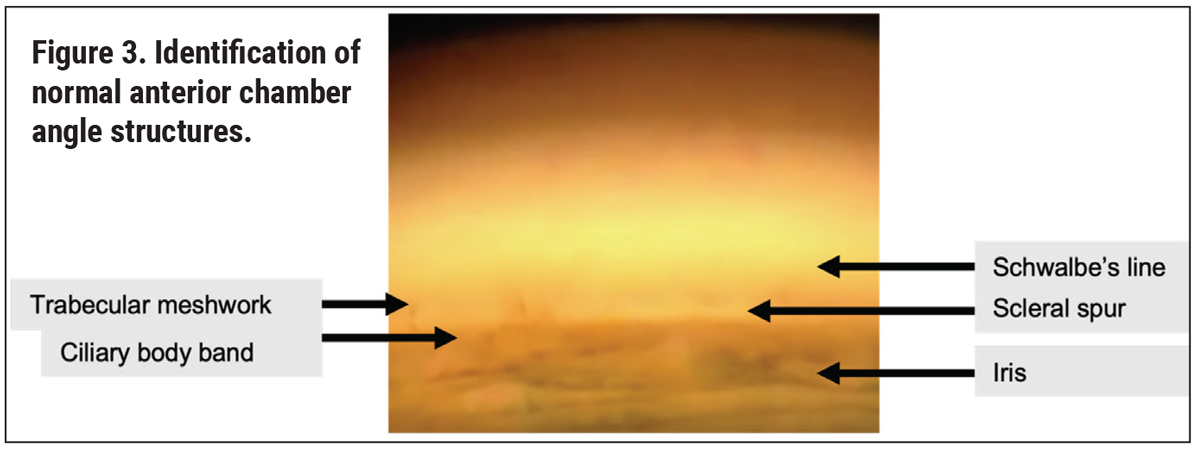

When identifying angle structures, it’s useful to first recognize landmarks. Particularly in individuals with a lightly pigmented trabecular meshwork, for whom a Sampaolesi’s line is present, or for whom there is significant bowing of the iris, this can be a challenging task. We find that detecting the scleral spur first is easiest since it’s one of the brightest, most prominent white boundaries, sandwiched between the dark ciliary body band and the pigmented trabecular meshwork.

Others may find it easier to use the corneal wedge technique, whereby the thin beam of light causes an inner and outer corneal reflection that intersects at Schwalbe’s line (the anterior border of the trabecular meshwork). This technique is best used in the superior and inferior angles. Other tips for feature recognition include starting with more diffuse illumination and reducing it only when structures are seen, as well as having the patient look towards the mirror of evaluation for a better view. In cases where the iris is too flat, having the patient look in the direction opposite of the angle may be necessary. In addition, sometimes when the angle is obscured by a steep midperipheral iris, tilting the lens in the direction of the angle you want to view can be effective.

After you identify the baseline structures, you can perform dynamic gonioscopy. The Zeiss, Posner, Sussman and Allen-Thorpe lenses are all ideal for indentation as they have smaller areas of contact onto the cornea.8 In contrast, the more commonly used Goldmann lens has a steeper curve and ineffectively indents the limbus rather than the actual cornea. Nevertheless, it is the most commonly used goniolens in clinical practice. When performing indentation gonioscopy, lightly press the gonio lens up against the cornea. When pressure is applied such that the globe is pushed back, forward focus adjustment of the slit lamp is then needed to bring a clear image into view. It should be noted that indentation can induce temporary folds in Descemet’s membrane which make visualization difficult. This can be overcome by use of a slightly wider and brighter light beam.

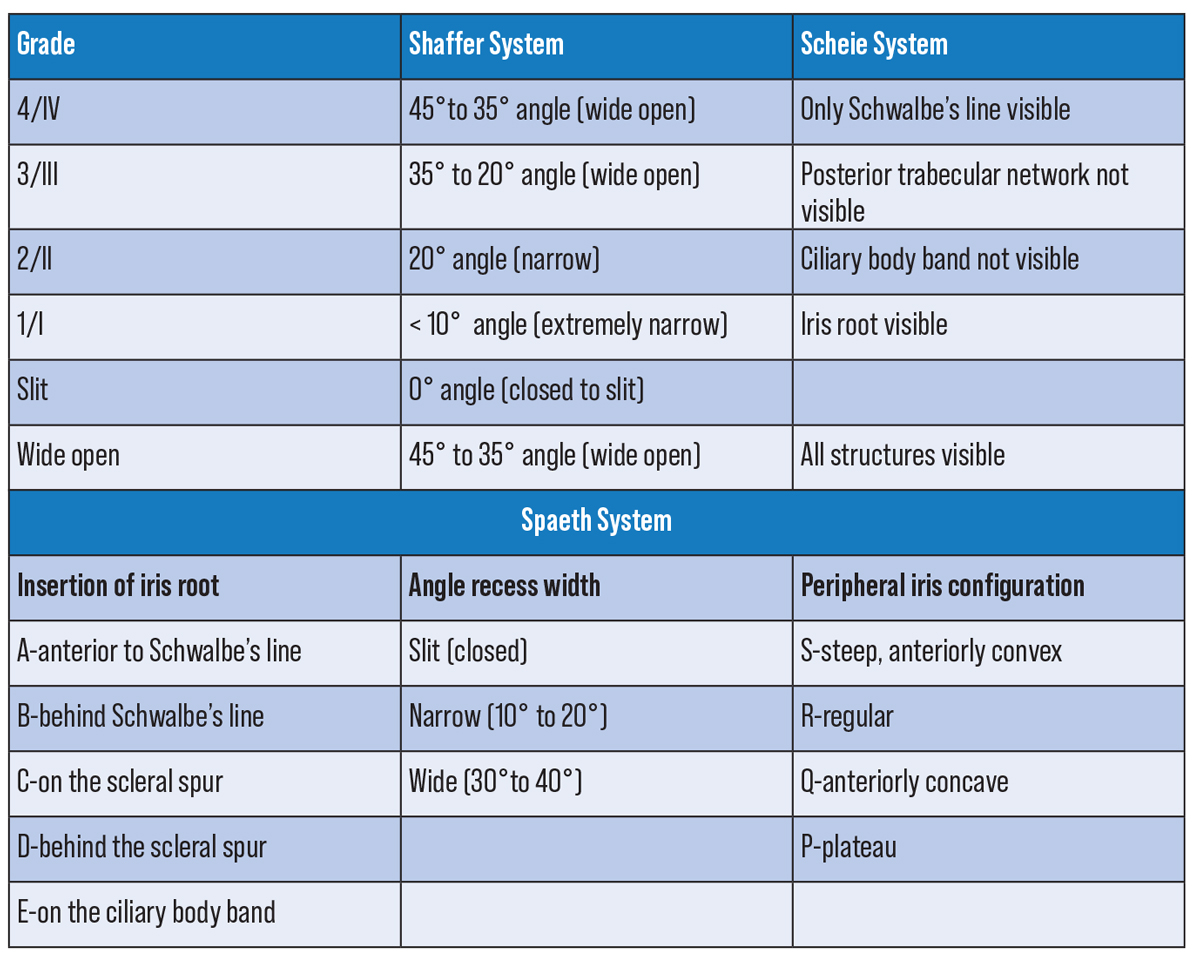

While there are many different methods of grading the angle, be it with the Shaffer, Scheie, or Spaeth classification system, it’s much more important to be able to accurately describe what you see. It’s helpful to go angle by angle describing visible structures, degree of pigmentation, whether or not PAS is present, angle of iris insertion and changes with indentation.

Here are some final tips, particularly for practitioners early in their training and careers:

• The right amount of pressure. First, be careful not to apply too much pressure on the cornea with your gonio lens. This can cause distortions in the cornea making visualization difficult and can also artificially open the angle. When placing the lens on the cornea, you want to be able to see a single uniform tear film. If it’s not uniform, you’ll see a bubble at the interface. In these instances, you want to gently slide the lens away from the bubble, taking care not to apply additional pressure, until the bubble is no longer present and the structures are visible. Don’t be afraid to remove the lens and reapply the coupling fluid if needed.

• Assistance through imaging. Second, if there is ever any question of degree of angle opening or abnormal pathology, ultrasound biomicroscopy and anterior segment optical coherence tomography are always helpful supplemental tools. Of course, they don’t replace the skill of gonioscopy.

• Practice! Practice! Practice! There’s no substitute for this. Gonioscopy.org is a very helpful resource for both becoming more familiar with the angle and to use as an atlas for identifying angle structures and abnormalities. With time and practice, thinking about the angle will become second nature to you and gonioscopy will soon become a routine part of your examination. Remember: If you don’t look for narrow angles, you’ll never find them.

This article has no commercial sponsorship.

Dr. Ramachandran is a fourth-year resident at NYU Langone’s Department of Ophthalmology. Dr. Al-Aswad is a professor of both ophthalmology and population health at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.The authors have no financial interest in any of the products discussed in the article.

1. Glaucoma Panel, Preferred Practice Patterns Committee. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2005:36.

2. Fremont, AM. Patterns of care for open-angle glaucoma in managed care. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2003 June;121:6:777-83.

3. Wu AM, Stein JD, Shah M. Potentially missed opportunities in prevention of acute angle-closure crisis. JAMA Ophthalmol. Published online May 12, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.1231.

4. Avoiding lawsuits after iridotomies. EuroTimes. Published April 26, 2014. https://www.eurotimes.org/avoiding-lawsuits-after-iridotomies/.

5. Thompson AC, Vu DM, Cowan LA, Asrani S. Risk factors associated with missed diagnoses of narrow angles by the Van Herick technique. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2018;1:2:108-114. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2018.08.002

6. Engelhard SB, Justin GA, Craven ER, Sim AJ, Woreta FA, Reddy AK. Malpractice litigation in glaucoma. Ophthalmology Glaucoma 2021;4:4:405-410. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2020.10.013

7. Zhang N, Wang J, Chen B, Li Y, Jiang B. Prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in the last 20 years: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;7:624179. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.624179

8. AAO Disease Review. https://www.aao.org/disease-review/principles-of-gonioscopy. Accessed June 15, 2022.