Symptomatic complaints associated with dry eye can be caused by a number of things, from something as complex as a systemic disease to something as simple as staring at the computer too long. Because of the variety of causes, getting to the bottom of a patient’s complaints isn’t always easy. However, with a systematic approach and an eye for certain telltale signs, physicians say you can figure it out. In this article, several ocular-surface disease experts share their tips on sussing out the cause of a patient’s dry eye.

What the Patient Says

| Useful Questions for Dry-Eye Suspects |

Have you experienced any of the following symptoms during the last week?

|

“Get a history of patients’ symptoms and delve into other things, such as elements of their environment that might be causing their symptoms,” says J. Daniel Nelson, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “What work do they do? Do they have any pets at home? Do they engage in any hobbies that involve chemicals, such as painting? Do they have allergies that might cause the symptoms? Maybe they have a contact sensitivity to makeup, or they’re putting on their makeup too close to their eyes. Is there maybe a sensitivity to something in their diet? What topical drops are they using and what preservatives might those contain? For all of these reasons, it’s important not to jump right into the exam. For someone with allergies, for example, relief may be as simple as washing his face and hands when he comes in from the wind and the dust outside.

“Also, though this is a simplistic way of looking at it, I listen to how they characterize their symptoms,” adds Dr. Nelson. “If they have an irritation of the ocular surface, they’ll complain of a burning like you’d feel from soap or shampoo, irritation like feeling sand or gravel, or itching like from a mosquito bite. If I don’t hear any of these types of symptom descriptions, for me that puts the patient in a separate, non-ocular-surface category of disease.” He says also to look for uncorrected hyperopia or presbyopia in patients who have symptoms of irritation but no obvious signs: “With uncorrected hyperopia or presbyopia, as patients age they have to focus so much it can cause a decreased blink rate and eye fatigue that mimic dry-eye symptoms.”

Physicians also make it a point to look for histories of diseases, both systemic and ophthalmic, that include dry eye as a sign and/or symptom. “Ask about diseases such as Sjögren’s, diabetes, thyroid, autoimmune disorders, lid diseases or rosacea,” says Ottawa’s Bruce Jackson, MD. “Those are key things you want to make sure you look for.”

Dr. Nelson offers some tips for trying to weed out systemic illnesses. “Patient’s with primary Sjögren’s syndrome will often show up in the ophthalmologist’s office first,” he says, “while patients with rheumatoid arthritis or lupus will often present in the rheumatologist’s office first. So, if someone comes from the rheumatologist’s office with complaints of dry eye and he has been diagnosed with systemic disease, your suspicion of the systemic illness as the cause should rise. To me, depending on the classification system you use, you need evidence of an autoimmune disease from blood testing [discussed below].” Physicians say to suspect Sjögren’s if you elicit complaints of dry mouth and/or vaginal dryness.

Certain medications, discovered in the patient’s history, can also contribute to dry eye, say physicians. “Antihistamines are a common contributor,” says Louisville, Ky., ophthalmologist Gary Foulks. “Also, anxiolytics, often taken at night, and other tranquilizers can decrease tear production. If you find the cause of the dry eye is a medication, talk to the patient’s primary-care doctor and let him know that the dry eye is—at the very least—being aggravated by the medication, and inquire about the possibility of using alternative drugs. Anxiolytics are usually used by a psychiatrist or geriatrician, and he can usually recommend something that doesn’t have such an anti-cholinergic effect. Oral Acutane has also been associated with meibomian gland dysfunction and dry-eye problems. If a patient has a history of mucosal inflammatory disease such as cicatricial pemphigoid or a reaction to a drug such as acute toxic epidermal necrolysis, these are severe problems that can be a systemic basis for dry-eye disease.”

Dr. Nelson says it’s also important to find out what the patient has been using for treatment of his dry eyes and whether it’s working or not. “If he truly has ocular surface disease and dry eye, artificial tears should help,” he says. “If the artificial tears aren’t helping, then something else is going on. You have to ask yourself: Is it really dry eye?”

“A number of other things can come into play,” adds Michael Lemp, MD, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at Georgetown University. “These include wearing contact lenses. Contact lens wear can be a problem if the patient has borderline tear production. The contact lens stresses the system and causes evaporative tear loss, pushing the person into being symptomatic. There are also iatrogenic causes like refractive surgery, which can sever the corneal nerves.” He says graft vs. host disease must also be ruled out in transplant patients.

One thing that Dr. Jackson says has really helped his diagnostic process is a modified questionnaire he developed, the Canadian Dry Eye Assessment, which is basically a condensed version of the the popular Ocular Surface Disease Index questionnaire. The bulk of it consists of questions about the frequency of particular symptoms or the circumstances during which the symptoms usually occur. (For a list of several of the CDEA questions, refer to “Useful Questions for Dry-Eye Suspects” on p. 28.)

“Using the questionnaire is something we hadn’t done in the past,” says Dr. Jackson. “Back then, we would usually just listen to the patient talk about his burning, irritated eyes. However, we’ve found that you have to be able to quantify their subjective complaints because otherwise patients will go on and on. I think the patient questionnaire has made a difference at our practice.”

What the Physician Finds

Though symptoms bring the patient to your office, the signs of disease will be the most helpful in making a diagnosis and gauging the severity of the dry eye, ophthalmologists say. Following is a discussion of key signs and what they might mean, as well as how to employ certain tests.

• Facial and lid exam. Physicians say it’s helpful to look for general signs of rosacea before you get closer to the eye with the slit-lamp exam. “Assess the blink rate and the lid closure,” says Dr. Jackson. “If there’s any abnormality of the lids, you must treat that. You won’t be successful in treating dry eye until you focus on that.”

|

| The appearance of obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction: pouting of orifice; loss of definition of cuss; and plugging.3

(Image courtesy Gary Foulks, MD/The Ocular Surface) |

- clear meibum;

- cloudy meibum;

- cloudy with debris (granular); or

- thick, like toothpaste.2

Dr. Foulks highlights other lid features to examine. “Look for any erythema of the lid margin,” he says. “The presence of abnormal telangiectatic vessels can indicate chronicity. Also, look for evidence of puckering of the meibomian gland orifice or even notching of the lid, which are other hallmarks of a chronic case of meibomian gland dysfunction. In terms of systemic disease associated with meibomian gland dysfunction and evaporative dry eye, the more common presentation is a rosacea patient who presents with a rosy complexion and prominent sebaceous glands and telangiectasia of the skin.”

Dr. Foulks says blepharitis is separate from MGD. “Posterior blepharitis implies inflammation, and it can be a component of meibomian gland dysfunction,” he says. “But they’re separate issues. So, meibomian gland dysfunction can occur even when there isn’t a lot of inflammation, and posterior blepharitis is inflammation that sometimes occurs as a component of meibomian gland dysfunction.”

Dr. Lemp says that, though MGD is a frequent cause of evaporative dry eye, it’s not the only cause. “You have to rule out lid problems like improper blinking, which can occur in patients with thyroid eye disease in whom the palpebral fissure is very wide,” he says. “In them, the surface is more exposed and there’s more evaporative tear loss. One thing we’ve found is that people who use computers more than three hours per day will have a decreased blink rate from staring at the screen, and will frequently report symptoms of dry eye. They may even have evidence of meibomian gland dysfunction because the muscles of the lids actually pump the oil glands, but when they’re not used as frequently they get lax and aren’t as effective at pumping out the oil.”

Dr. Lemp says the key to keep in mind when evaluating a patient and eventually developing a treatment plan is that the 2007 Dry Eye Workshop reported aqueous deficiency and evaporative dry eye as the two major sub-types of the disease. “In one, aqueous deficiency, the lacrimal gland doesn’t perform well, and in the other, evaporative loss, the meibomian gland usually isn’t performing well,” Dr. Lemp says. One caveat though, say physicians, is that it can be difficult to say definitively that a patient has only evaporative or aqueous-deficient dry eye because the two forms often co-exist, especially in severe cases.

• Corneal and conjunctival exam. “The other condition to look for is conjunctival chalasis,” says Dr. Foulks. “Here, the symptoms the patient complains of will be a bit different from dry eye. He’ll complain of pain, and significant foreign body sensation or of watery eyes, even though his eye is dry. This is because when anything rests on the lower lid, as the conjunctiva may be doing in this case, it will give the feeling of water in the eye.” Physicians say keratitis also may be present.

|

| At the worst end of the meibomian expression spectrum, the secretion comes out thick, like a paste.3

(Image courtesy Gary Foulks, MD/The Ocular Surface) |

“The other step you can take when trying to determine if there’s a deficiency in aqueous production is look at the tear meniscus at the slit lamp,” Dr. Foulks adds. “Typically, in an aqueous deficiency case, there will be a reduction in tear meniscus height, usually at the inferior lid margin. In evaporative dry eye, however, that’s not always so, since the tear volume will be sufficient due to the reflex tearing maintaining it. So, if you get a significant loss of tear meniscus, that’s a good indicator you’re dealing with aqueous-deficient dry eye.” Also, debris in the tear meniscus can also point to aqueous deficiency, says Dr. Jackson. “Or there may be a soapy appearance indicative of meibomian gland dysfunction.”

Physicians say Schirmer’s testing, aimed at determining the rate that the eye can produce tears, can help contribute to your diagnosis, but that it has limitations. “We try to stay away from relying on Schirmer’s test results except on the severe level of dry-eye disease,” says Dr. Jackson. “Often, someone in a clinic will get a Schirmer’s of 15 and, even though the patient has dry eye, the person will still say, ‘The Schirmer’s is good, no problem here.’ Again, it may be a dry eye due to a lipid deficiency or meibomian gland disease, or allergy may be playing a role. These are some reasons why Schirmer’s tests can throw people off.”

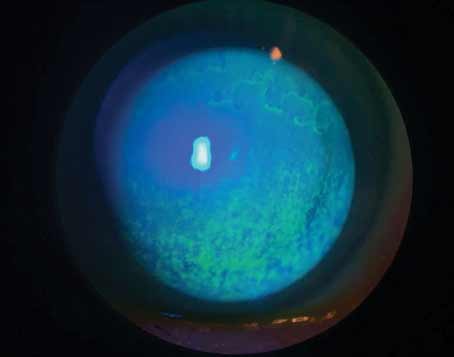

• Staining. Even for the busy clinician, physicians say performing some simple stains can be worthwhile.

“The pattern of ocular surface staining or lack thereof with instillation of fluorescein or lissamine green will confirm that there’s surface damage consistent with one of the types of dry eye,” says Dr. Foulks, “but it will also help give the level of severity of the disease.

“In aqueous-deficient dry eye the nasal staining is greater than temporal staining of the conjunctiva with lissamine green,” says Dr. Foulks. “And there’s some evidence that significant staining of the temporal conjunctiva is an indication of dry eye associated with Sjögren’s. Fluorescein, on the other hand, is used for corneal stains. Classically, with aqueous-deficient dry eye, it appears as interpalpebral or inferior staining with fluorescein. But with meibomian gland dysfunction, the staining tends to be in the lower half of the cornea. Rarely do you see staining in the upper third of the cornea with dry eye unless it’s very severe disease.” Several other physicians agree that florid conjunctival staining can be a very strong indicator of a systemic autoimmune disease, and you should begin questioning the patient about symptoms such as joint pain, constipation and diarrhea. “You’ll begin to pick up hints about what’s going on,” says Dr. Nelson.

“If there’s no staining in general, it tells you that the patient probably doesn’t have a systemic disease involving the lacrimal glands such as Sjögren’s,” adds Dr. Nelson. “Also, corneal staining often correlates with symptoms. For example, someone with a burning or foreign body sensation will often show staining, as well. Also, if someone comes in with conjunctival lissamine green staining, this can sometimes be the result of a toxic reaction, such as from a drug with a certain preservative. This will usually go away if you stop the drug. Whereas in Sjögren’s patients, lissamine green staining is there almost forever. Also, it doesn’t correlate with pain; that’s not the source of pain in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome dry eye.”

• Other testing. Some surgeons have begun using tear osmolarity testing to evaluate patients. Osmolarity testing involves taking a sample of a patient’s tears and measuring its milliosmoles per liter. “It tells you whether someone has dry eye or not, and whether it’s mild, moderate or severe,” says Dr. Lemp, who has a financial interest in the device. “It can also show how a patient is responding to treatment for his dry eye. What it doesn’t tell you is the subtype of dry eye that’s present; in other words, whether it’s aqueous-deficient or evaporative.

“The osmolarity measurement has different levels, though it’s not absolute like IOP can be in glaucoma,” Dr. Lemp continues. “It uses 308 mOsm/liter as the cutoff between normals and dry eye. We then use 316 mOsm to differentiate between mild and moderate dry eye, and someone with 328 mOsm is more in the moderate/severe to severe categories.”

Another device, recently approved, is the LipiView Interferometer by TearScience. With LipiView, the clinician positions the patient’s eye in front of an illumination source that’s aimed at the tear film. Rays from the light source pass through the tear film and reflect into a camera, forming an interference pattern that can be compared to an interferometry scale to help measure the thickness of the oil layer of the tear film and catch a patient with evaporative dry eye. Physicians note, however, that even with a lipid layer analysis, you’ll still have to look to see if the patient has aqueous deficiency, as well. “Another device, the Keeler Tearscope, looks at qualitative patterns of the tear film,” says Dr. Foulks. “But, again, it tells you if there are problems with the lipid layer of the tear film but doesn’t exclude aqueous-deficient dry eye.”

|

| When a patient presents, physicians say to look for signs of ocular rosacea in determining a cause of dry eye.

(Image courtesy Bruce Jackson, MD.)

|

If you suspect a systemic cause for the dry eye, further testing may be necessary. These include Sjögren’s SSA/SSB antibody tests and a rheumatoid factor. You might also consider having the patient see a rheumatologist, say physicians. For a definitive diagnosis of dry mouth in a Sjögren’s suspect, you may have to send the patient to a dentist or oral surgeon. Failing that, Dr. Nelson says “I often use a simple screening test: I ask the patient if he can chew a soda cracker and swallow it without water, then I have him stick out his tongue to see if it looks moist or dry.”

Dr. Nelson says that the good news is that after you diagnose the patient and initiate a treatment for his dry- eye disease, it gets easier to monitor his progress with the treatment regimen. “A patient coming in with dry-eye symptoms is analogous to a compressed accordion—just like the accordion can only be compressed so far, the patient can only feel so much pain,” he says. “So, he just feels bad all the time. He can’t tell what exactly is bothering him. But as you start clearing up the inflammation, getting the meibomian glands working again and so on, all of a sudden the accordion expands and he can feel things more specifically, and can tell you what bothers him more. He starts to be able to tell the difference between a ‘good day’ and a ‘bad day,’ and can tell when things are starting to get worse, ultimately allowing you to intervene sooner with treatment.”

1. Jackson WB. Management of dysfunctional tear syndrome: A Canadian consensus. Can J Ophthalmol 2009;44:385-94.

2. Kelly K. Nichols. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Introduction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4:1917-1921.

3. Foulks G, Bron A. Meibomian gland dysfunction: A clinical scheme for diagnosis and classification. The Ocular Surface 2003;1:107-126.