The Benefits of DSEK/DSAEK

As a review, DSEK involves first stripping away diseased endothelium and Descemet's membrane, about 7 µm in thickness, by going through a corneal incision. The surgeon then dissects healthy endothelium from a donor cornea (if a microkeratome is used for this step the procedure is known as DSAEK) folds the excised tissue carefully, then inserts it through a 5-mm incision in the recipient's eye. The donor tissue is unfolded in the host's anterior chamber and placed on the posterior cornea. An air bubble, left in the eye for various lengths of time depending on the technique being used, keeps it in place, giving time for the pumping action of the endothelium to help the donor tissue bond to its new host.

Surgeons say this less-invasive surgery, though it can be technically challenging, offers benefits over standard penetrating keratoplasty that make it very valuable.

"The visual results are what make me enthusiastic about this procedure," says Mark Gorovoy, MD, of Fort Meyers, Fla. "It's like comparing the vision of phaco patients to that of extracap patients after a month. It's that extreme. For example, in patients with no known macular pathology, 80 percent will see 20/40 corrected by six weeks. That number goes up to 90 percent at three months. A PK patient, though, by comparison, might only be at 20/400 best-corrected for a year or two postop."

Surgeons say the procedure leaves a much stronger eye than PK, as well. "The reason I got into this procedure is that PK patients have fallen and hit their eyes and their wounds have ruptured because they don't heal very strongly," says Frank Price, MD, of Indianapolis. "One of the important aspects of DSEK or DSAEK is that we use small incisions that leave the eye very strong and not as susceptible to rupture."

Dr. Price says the procedure is also a boon to cataract surgeons who have to deal with cataract patients who also need transplants.

"Conventionally, cataract surgeons would put off operating on Fuchs' dystrophy patients forever," he says. "This is because if they have the [PK] transplant it can take a year or two for them to see better and a lot of patients don't have good vision afterward, especially elderly patients. But now, with DSEK/DSAEK, you don't really have that fear, so surgeons can just go ahead and do the cataract surgery. If the patients do well, fine. If they don't, they can have a DSEK and be back doing well in a month or two."

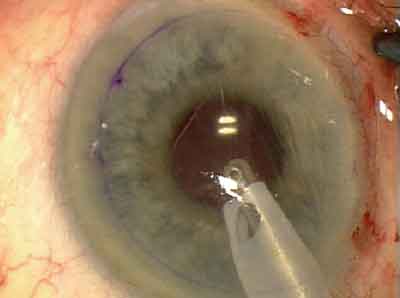

|

| An irrigating Descemet's stripper scores Descemet's membrane 9 mm around. All images: Mark Gorovoy, MD |

A procedure related to DSEK, deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) appears to be losing popularity to DSEK, at least with the transplant surgeons we spoke to. The reasons they give are DLEK's average visual results aren't as sharp as DSEK's, though its grafts have a lower rate of dislocation (since it involves transplanting a piece of tissue about 150 µm thick). The surgeons quoted in this are focusing their energies primarily on the stripping procedures of DSEK and DSAEK, and trying to perfect their outcomes with them.

Overcoming Complications

The experts say the best way to get good outcomes with DSEK/DSAEK is to minimize its most common complications: graft dislocations; primary graft failure and over-manipulation of the graft, which influences the other two complications. Here are surgeons' thoughts on avoiding these problems:

• Graft dislocations. Portland, Ore., surgeon Mark Terry has developed a way to help DSEK grafts adhere with more regularity.

"The advantage for the patient of DSEK is that the stripping of Descemet's membrane creates a smoother interface for the recipient bed than DLEK," says Dr. Terry. "On scanning electron microscopy, after resection of the recipient posterior stromal block of tissue, we found the DLEK interface to be very smooth. However, it was smooth like a rug where the fibers of the rug had been cut evenly all the way across. On the other hand, the DSEK interface was glassy smooth, with no appearance of cut fibers at all.

"The glassy smooth DSEK interface allows you to get better vision, and get it faster, than with DLEK. But it's so smooth the donor disk has a higher chance of sliding in the horizontal meridian as well as falling posteriorly." To combat this, he has modified the interface to help with adherence.

"If you want something to stick to glass, you have to roughen it," he says. "Like painting a window. If you try to just paint the glass, the paint will just run down the pane. But if you roughen the window with sand paper, then the paint will stick. Now, we can't roughen the whole DSEK interface surface, or we'd defeat the whole goal of better vision. So, we take a hybrid approach. We use an instrument [the Terry Scraper by Bausch & Lomb] to scrape the peripheral recipient bed with a width of about 1 mm just inside the stripped edge all around the bed. Then, we put our graft tissue in place. The edges of the tissue seal down beautifully with the rough edge, but the center is still glassy smooth and allows better vision. In this way, we get the best of both worlds: better vision with DSEK but with the adhesion advantages of DLEK."

In a study soon to be published in the journal Cornea on his first 100 consecutive cases in which he used this technique, he reports a 4-percent dislocation rate, with one of the dislocations being a result of primary graft failure. "The other three dislocations didn't dislocate until the second, third or fourth day after surgery, and were probably due to some patient interaction," Dr. Terry says. "So, a 4-percent dislocation rate is comparable to what we have with DLEK, and it's certainly better than the 35 percent rate reported by a recent survey reported at the Eye Bank Association of America meeting in June 2006 of 29 novice DSEK surgeons who did not use peripheral scraping to prepare the recipient bed."1 A video of his technique will be presented at the 2006 Academy meeting in Las Vegas.

|

| Florida surgeon Mark Gorovoy uses an I/A instrument to strip Descemet's. |

Chicago's Thomas John, MD, who calls the DSEK procedure descemetorhexis with endokeratoplasty (DXEK), sees the benefit of roughening the edges, and has developed an instrument with ASICO to do this, the John DXEK/DSAEK Stromal Scrubber. "It has a curvature and a roughened tip so the peripheral roughening of the stroma is done more easily," he says.

To help battle dislocations, Dr. Price leaves the air bubble in the eye for a slightly longer time, massages the corneal surface and also developed the idea of adding corneal incisions.

"Dislocations are a problem that I don't think will ever be eliminated," says Dr. Price, "at least in the near future. We had our detachment rate down to 1 percent in a series of about 200 eyes, and we've been getting them again. It's hard to say precisely why they occur in all instances. Sometimes they just happen. Some of the things we've done that improved the attachment of the donor cornea include leaving the air in the eye a little longer. In the original techniques, we'd only leave the air in for about five minutes. I now leave it in for eight minutes. It may seem to be a small amount of time, but it seems to have made a difference."

Dr. Price says that in 10 to 15 percent of the cases there seems to be fluid trapped between the two pieces of cornea that might contribute to dislocations.

"That fluid creates a kind of space that keeps the donor from coming into contact with the recipient," he says. "I use a Lindstrom LASIK roller to massage the surface of the cornea, hopefully to squeeze out some of the fluid. We're not entirely certain that this is effective, but it appears that you're probably massaging out some of it. Also, an incision that goes all the way through the recipient and into the interface between the donor and the recipient sometimes gets a fair amount of fluid out." He uses a Trimond diamond blade from Mastel to make the incisions. "I initially used a metal blade but the diamond goes through much easier," he says. "And since I usually make my incisions after the donor is in place and the diamond goes through pretty smoothly, you're less likely to dislodge or wrinkle the donor." He places the incisions at 12, 3, 6 and 9 o'clock, about 1 mm in from the edge of the donor graft. He also uses a metal Mastel blade with a square tip to torque the incisions open a bit to let more fluid out.

Dr. Gorovoy has recently incorporated Dr. Price's incision method, but says he's also decreased his dislocation rate by leaving the air bubble in for an hour postop. He estimates the two techniques have reduced his dislocation rate from a little over 10 percent down to 7 percent.

Chicago's Dr. John says Trypan Blue to stain the donor disk helps the surgeon identify the correct orientation of the disk should it flip after being introduced into the anterior chamber. "The stain will color the cut, exposed stromal surface of the donor disk, so you'll know which side is which," he explains. "By the time you finish the procedure, about 75 percent of the stain is gone. There's no stain on the donor disk the next day."

• Primary graft failure/tissue manipulation. Surgeons say that, in many cases, when a graft fails to adhere it's because the surgeon was too aggressive in handling it, and killed endothelial cells.

In a study of Dr. Price's first 200 DSEK cases, he reports seven primary graft failures (3.5 percent).2 The study notes, however, that there was only one in the second 100 cases, which were primarily done using the microkeratome to harvest the graft.

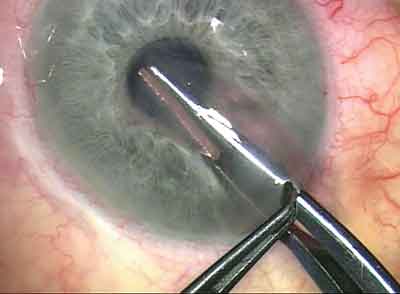

|

| The surgeon inserts the folded donor endothelial button into the recipient. |

Dr. Gorovoy says he prefers to use forceps that hold the folded tissue only at one point rather than along its entire length, a situation in which the tissue can be crushed more easily.

Dr. Terry says he and his colleagues have developed some techniques to help protect the endothelium. "If the surgeon is going to be using a microkeratome to cut the donor graft, he has to make sure not to allow the endothelial tissue to touch the metal of the artificial anterior chamber," says Dr. Terry. "We recommend surgeons use Healon to protect the endothelium during mounting, processing and dismounting of tissue from the artificial anterior chamber of the microkeratome. We also recommend that surgeons leave the donor tissue on the post of the microkeratome's artificial anterior chamber and not remove it from the post when they lift off the helmet or metal cap from the tissue. If you don't do this, you'll have a high percentage of corneas with anterior chamber collapse and endothelial damage during dismount."

Dr. Terry also doesn't believe it's a good idea to further decrease the size of the incision used to insert the graft. "Some surgeons are experimenting with different techniques of insertion, such as using a 3-mm incision and triple folding the tissue to squeeze it through," he says. "But the more you squeeze the tissue through a smaller incision, the more endothelial damage you get and the higher the likelihood of graft dislocations and primary graft failure … . Our latest prospective data demonstrates that when you fold the donor tissue, you lose more endothelial cells than if you don't fold it, especially over the first two years postop. And if you fold it more than once to get it through a 3-mm incision, you likely lose even more cells. However, good prospective data on cell loss with 3-mm incision EK surgery is needed for statistical comparison."

As for endothelial cell loss postop, Dr. Terry says in his study, the largest prospective study of EK with cell-loss data, there was a 25-percent loss of cells at six months in 100 patients, and that this percentage loss accelerated faster over two years in folded v. non-folded donor tissue.3 "The cell loss appears comparable to what is seen with PK surgery," says Dr. Terry.

General Surgical Techniques

In addition to the techniques that surgeons use to decrease dislocations and graft failures, other small steps add up to better procedures.

"To cut the donor tissue, I've standardized the process by using the Moria ALTK system with a 300-µm head in pretty much every case," says Dr. Gorovoy. "I'm not really measuring donor thickness, and I don't think it makes that much of a difference. I'll be reporting at this year's Academy meeting the effect of various final corneal thicknesses on vision."

Some surgeons recommend using the irrigation/aspiration unit from a phaco machine to work inside the recipient eye.

"For the corneal surgeon just starting out with endothelial transplants, the hardest thing to do, next to manipulating the tissue gently, is getting it to unfold," says Dr. Gorovoy. "I think the key here is to minimize the manipulations, as well. My approach is to use the I/A unit to aspirate out Descemet's and unfold the tissue. To me, that's the quickest, most atraumatic way to unfold it. It's very uniform. I use the I/A for the whole operation, for the stripping as well."

Dr. John says using viscoelastic in the recipient's eye can help you maintain control during the procedure. "Many surgeons use fluid in the anterior chamber during the various steps of the procedure, such as scoring and detaching Descemet's membrane," he says. "The problem is, that makes the procedure more complex, because when you use fluid, your left hand will be tied up holding the needle that introduces fluid into the anterior chamber. Alternatively, if you're using an anterior-chamber maintainer, once you remove it, you may need to use a suture to seal the wound tight because you introduced an instrument that had to be screwed in through the incision site. But, with viscoelastic, you've got a more controlled environment in which to score and remove Descemet's membrane." He removes all the viscoelastic before placing the donor.

In addition, Dr. John, like several other surgeons, performs the procedure under topical anesthesia, though he says it's best to be experienced with the procedure before moving on to the use of topical.

Dr. John has developed an instrument with ASICO called the John DXEK/DSAEK Dexatome spatula that he says is helpful for the stripping step of the procedure. He has no financial interest in the instrument.

"We've always worked on 'the floor' of the eye in ophthalmology," he says. "We work on the lens, the retina, the ocular surface, the vitreous cavity and so on. But with DXEK, we're working on the 'ceiling,' above the instrument. The curvature of the Dexatome is such that once you enter the eye, you can do the 360-degree scoring and detach Descemet's as a single disk almost every time without needing to create a second entry site."

Best- and Worst-Case Scenarios

The patient presentation will dictate how surgeons approach an endothelial transplant case. Here's how they change tacks if they have to.

"The ideal patient is someone with a posterior chamber lens, intact capsule and a round pupil," explains Dr. Gorovoy. "The most difficult is someone with loss of iris with a very large pupil and with a sutured posterior chamber lens and a glaucoma shunt.

"Patients who don't have the iris-lens-capsule diaphragm are always more difficult, because we're depending on the initial large air bubble to hold the tissue in place up against the stroma. But in these sorts of eyes the air bubble management is difficult, especially if they have a shunt as well, because the air wants to go to the posterior chamber and up the shunt. In these patients, you also have to worry about pupillary block, because a lot of air goes into the posterior chamber. Then, when the patient's lying face up at home that night the air comes forward into the anterior chamber and causes pupillary block. So, you really have to warn patients to watch for any pain or other symptoms, and instruct them how to position themselves at night." He says the only patients who can't undergo DSAEK are those whose corneas are so opaque the surgeon can't see well into their anterior chamber.

Dr. Terry says that, for patients who have had a previous vitrectomy with an anterior chamber lens, he will perform DLEK rather than DSEK. "The reason is when you do DSEK, you have to have an air bubble that you can leave in the eye to help hold tissue in place for the night of surgery and the day after. When the patient has had a vitrectomy and an anterior chamber lens, the problem with DSEK is that as soon as he sits up after an hour of lying down postop, the air bubble goes right through the pupil to behind the iris, and is no longer available to support the transplanted tissue. But with DLEK, we get such good adhesion of the tissue to the recipient bed that we can routinely remove the air bubble at the end of surgery. That's why we perform DLEK in these patients, we know the tissue will stick and the bubble won't be necessary." He notes, however, that if the AC lens is unstable, he'll take it out and place a posterior chamber lens and do DSAEK.

Though performing DSEK involves a learning curve, surgeons say that if you take a course and don't get discouraged, you can succeed with it.

"You have to persist with it," says Dr. Gorovoy. "You have to make it work and not say, 'if it doesn't work I can do a PK.' You have to say that you will no longer do a PK for these patients. Doing a PK is a zero-case scenario."

You can reach the surgeons from the article at the following e-mail addresses: Dr. John, lasikcornea@gmail.com; Dr. Gorovoy, mgorovoy@gorovoyeye.com; Dr. Terry, mterry@deverseye.org; Dr. Price, fprice@pricevisiongroup.net.

1. Weiss JS, Mokhtarzadeh M. DSAEK in the real world—An analysis of dislocation rates. Presented at the annual meeting of the Eye Bank Association of America, Toronto 2006.

2. Price FW, Price MO. Descemet"s stripping with endothelial keratoplasty in 200 eyes: Early challenges and techniques to enhance donor adherence. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:3:411-8.

3. Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty visual acuity, astigmatism, and endothelial survival in a large prospective series. Ophthalmology 2005;112:9:1541-8.