Gene therapy for congenital blindness has taken another step forward, say researchers from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Three adult patients previously treated in one eye received the same treatment in their other eye, and the patients became better able to see in dim light; two were able to navigate obstacles in low-light situations. No adverse effects occurred.

Neither the first treatment nor the readministered treatment triggered an immune reaction that cancelled the benefits of the inserted genes, as has occurred in human trials of gene therapy for other diseases. The current research targeted Leber congenital amaurosis, a retinal disease that progresses to total blindness by adulthood. The work was reported in

Science Translational Medicine.

“Patients have told us how their lives have changed since receiving gene therapy,” said study co-leader

Jean Bennett, MD, PhD, the F.M. Kirby professor of ophthalmology at Penn. “They are able to walk around at night, go shopping for groceries and recognize people’s faces—all things they couldn’t do before. At the same time, we were able to objectively measure improvements in light sensitivity, side vision and other visual functions.”

|

LCA is a group of hereditary retinal diseases in which a gene mutation impairs production of an enzyme essential to light receptors in the retina. The study team injected patients with a vector, a genetically engineered adeno-associated virus, which carried a normal version of a gene called RPE65 that is mutated in one form of LCA.

The researchers in the current study previously carried out a clinical trial of this gene therapy in 12 patients with LCA, four of them children aged 11 and younger when they were treated. Exercising caution, the researchers treated only one eye—the one with worse vision. This trial, reported in October of 2009, achieved sustained and notable results, with six subjects improving enough to no longer be classified as legally blind.

The research team’s experiments in animals had showed that readministering treatment in a second eye was safe and effective. While these results were encouraging, the researchers were concerned that readministering the vector in the untreated eye of the patients might stimulate an inflammatory response that could reduce the initial benefits in the untreated eye.

“Our concern was that the first treatment might cause a vaccine-like immune response that could prime the individual’s immune system to react against a repeat exposure,” said Dr. Bennett. Because the eye is immune-privileged, such a response was considered less likely than in other parts of the body, but the idea needed to be tested in practice.

As in the first study, retina specialist Albert M. Maguire, MD, a study co-author, injected the vector into the untreated eyes of the three subjects at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The patients had been treated one and a half to three years previously.

The researchers continued to follow the three patients for six months after readministration. They found the most significant improvements were in light sensitivity, such as the pupil’s response to light over a range of intensities. Two of the three subjects were able to navigate an obstacle course in dim light, as captured in videos that accompanied the published study.

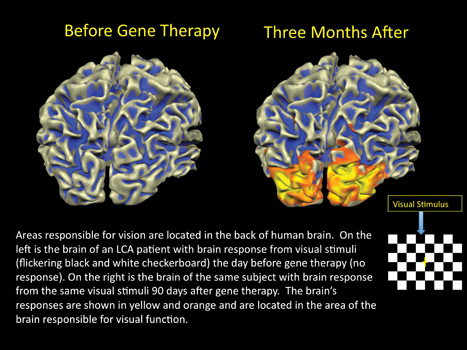

There were no safety problems and no significant immune responses. There was even an unexpected benefit—the fMRI results showed improved brain responses not just in the newly injected eye, but in the first one as well, possibly because the eyes were better able to coordinate with each other in fixating on objects.

The researchers caution that follow-up studies must be done over a longer period and with additional subjects before they can definitively state that readministering gene therapy for retinal disease is safe in humans. However, said Dr. Bennett, the findings bode well for treating the second eye in the remaining patients from the first trial—including children, who may have better results because their retinas have not degenerated as much as those of the adults.

Further, Dr. Bennett added, the research holds promise for using a similar gene therapy approach for other retinal diseases. Dr. Ashtari said that fMRI may play a future role in helping to predict patients more likely to benefit from gene therapy for retinal disease.

Don’t Dismiss Fields, Photos

Increased reliance on newer technologies—beyond visual field testing and straightforward fundus photography—to evaluate patients with and suspected of having open-angle glaucoma may undermine patient care.

A study published in January’s

Ophthalmology focused on trends in eye-care provider use of three methods for evaluating patients with open-angle glaucoma or suspected glaucoma: visual field testing, fundus photography and other ocular imaging technologies. Among these newer imaging technologies, the three most commonly relied upon approaches are confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, scanning laser polarimetry and optical coherence tomography.

The findings were based on claims data of 169,917 individuals with open- angle glaucoma and 395,721 individuals suspected of having glaucoma aged 40 years and older enrolled in a national managed-care network between 2001 and 2009. “Over the past decade, we found a substantial increase in the use of newer ocular imaging devices and a dramatic decrease in the use of visual field testing in the management of patients with and suspected of having open-angle glaucoma by ophthalmologists and optometrists,” says lead author

Joshua D. Stein, MD, MS, a glaucoma specialist at the University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center. “Our results indicate that the odds of a patient undergoing visual field testing decreased by 36 percent from 2001 to 2005, by 12 percent from 2005 to 2009, and by 44 percent from 2001 to 2009. By comparison, the odds of undergoing testing using the newer ocular imaging devices increased by 100 percent from 2001 to 2005, by 24 percent from 2005 to 2009, and by 147 percent from 2001 to 2009.”

Dr. Stein notes that, “Until these newer imaging devices can be demonstrated to identify the presence of open-angle glaucoma and capture disease progression as well as more traditional methods do, providers should use these devices as an adjunct to—not a replacement for—visual field testing and fundus photography.” Such findings suggest that greater efforts need to be made to educate eye-care providers about the importance of visual field testing in glaucoma management.

Several factors likely contribute to the recent shift to newer technologies. The newer imaging procedures are painless, can be performed quickly, require little patient cooperation, do not rely on subjective patient input and often can be obtained without dilation of the patient’s pupils. By comparison, visual field testing takes longer to perform, requires more patient effort and is largely subjective.

Financial incentives may also drive use of these newer technologies. Since the imaging devices are expensive to purchase, the more tests eye-care providers order, the quicker they can recoup equipment costs and eventually generate revenue.

(For a more extensive discussion of this topic, see Glaucoma Management, p. 70.)

British Study: Can Vitamin D Combat

Aging Vision Loss?

Researchers in Britain have found that vitamin D reduces the effects of aging in mouse eyes and improves the vision of older mice significantly. The researchers hope that this might mean that vitamin D supplements could provide a simple and effective way to combat age-related eye diseases in humans.

The research, by a team from the Institute of Ophthalmology at University College London, was published in the journal

Neurobiology of Aging.

The researchers identified two changes in the eyes of the mice that they think accounted for this improvement:

• The number of macrophages was reduced considerably in the eyes of the mice given vitamin D. Macrophages work to fight off infections, but in combating threats to the aged body they can sometimes bring about damage and inflammation. Giving mice vitamin D not only led to reduced numbers of macrophages in the eye, but also triggered the remaining mac-rophages to change to a different con-figuration. Rather than damaging the eye, the researchers think that in their new configuration macrophages actively worked to reduce inflammation and clear up debris.

• There was also a reduction among treated mice in deposits of amyloid beta, a toxic molecule that accumulates with age. Inflammation and the accumulation of amyloid beta are known to contribute, in humans, to an increased risk of age-related macular degeneration. The researchers think that, based on their findings in mice, giving vitamin D supplements to people who are at risk of AMD might be a simple way of helping to prevent the disease.

Professor Glen Jeffery, who led the work, said, “When we gave older mice the vitamin D we found that deposits of amyloid beta were reduced in their eyes and the mice showed an associated improvement of vision. People might have heard of amyloid beta as being linked to Alzheimer’s disease, and new evidence suggests that vitamin D could have a role in reducing its buildup in the brain. So, when we saw this effect in the eyes as well, we immediately wondered where else these deposits might be being reduced.” REVIEW