|

CMS announces a gaping cut in cataract reimbursements, eating a hole in the part of your net revenue that you had earmarked for retirement. Your partner goes out sick for six months. A tornado destroys the only office where you practice—fortunately, when no one is there. All of these setbacks can seem like more than you can handle. But none compare to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I don’t think any of us have ever envisioned a situation in which basically entire communities, nations and the world are very significantly shut down or constricted in activity all at the same time, or in short sequential time frames,” says Minneapolis surgeon David Hardten, MD. “That’s basically the situation we find ourselves in now. For anything else that happens to us in practice or in our professional or personal lives, there’s always some sort of contingency plan that we can use to figure out a solution. But there’s no contingency plan for this pandemic.”

At least not yet. Cataract surgeons and comprehensive ophthalmologists venture into a brave new world this month, puzzling over how to recover from a month-long virtual shutdown caused by the virus. Here’s how they’re doing it.

Why Open Ophthalmology Now?

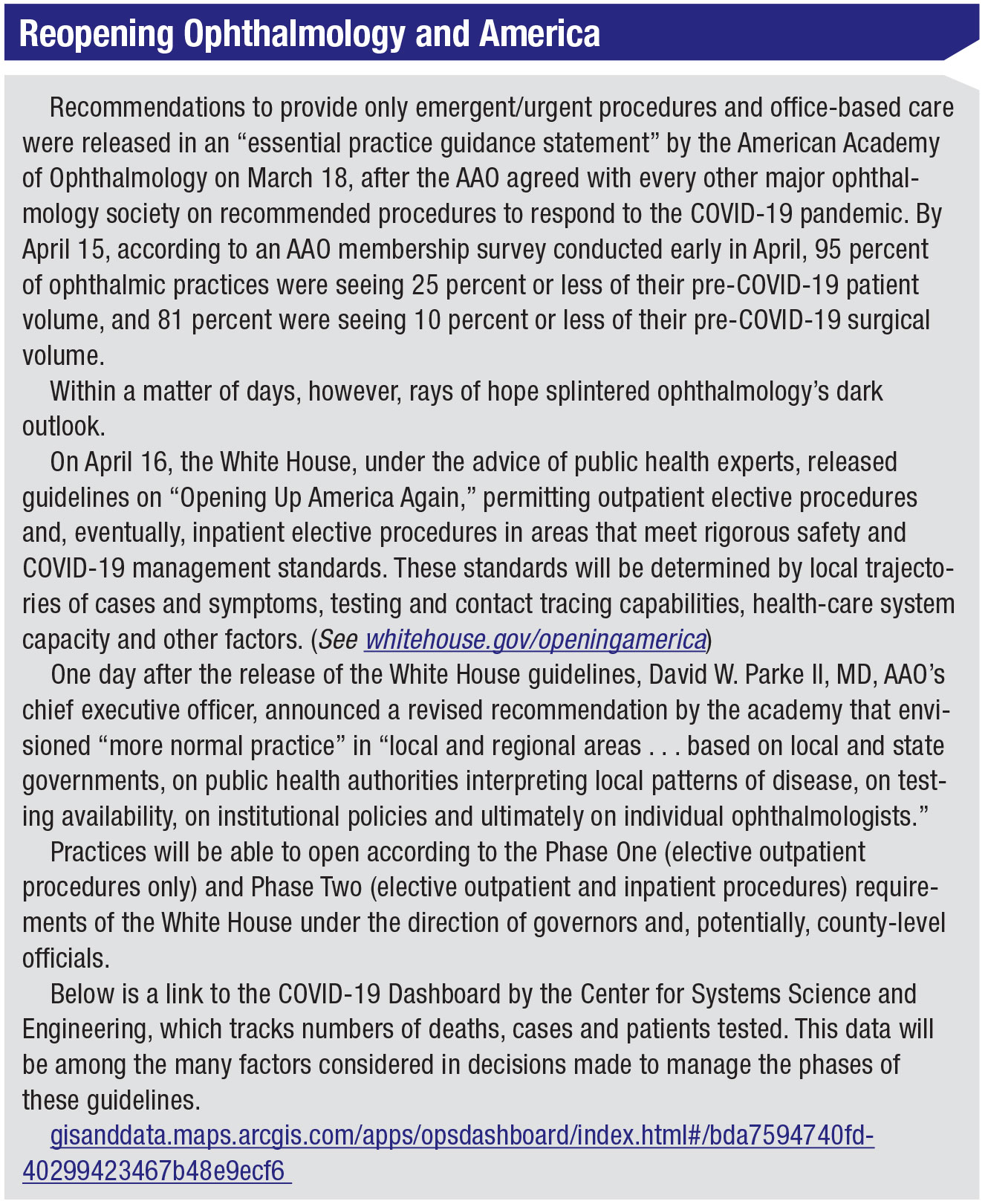

“Patients need ophthalmic care,” says David W. Parke II, MD, explaining the rationale behind the decision to recommend reopening ophthalmology care after restricting scope of practice to emergent/urgent care and procedures for 30 days. The chief operating officer of the American Academy of Ophthalmology continues: “Much has been deferred because of COVID-19 for patient and ophthalmology office safety reasons. Some areas of the country are seeing decreases in new cases, and many in the public health community believe that careful loosening of economic lockdowns are prudent—on a local or state basis—so long as certain public health conditions are met.”

Dr. Parke’s call for opening ophthalmology came on April 17, one day after the White House released a plan for opening America that will be guided in large part by public health experts monitoring regional patterns of COVID-19. (See “Reopening Ophthalmology and America, p. 30”)

Some cataract surgeons and comprehensive ophthalmologists, however, haven’t been won over by the recent decisions to encourage the return of routine office visits and elective procedures. These besieged doctors are quick to point out that their opportunity to increase patient flow will be controlled at highly-variable county or state levels, sometimes without their studied knowledge of the ever-changing numbers of open hospital beds, COVID-19 cases and symptoms and other factors that will need to be deemed acceptable to get ophthalmic care closer to normal.

“While it’s helpful to have some further clarity on the road to slowly doing more work, I believe the pathway will continue to be tough to navigate, as the regional health-care COVID-19 impact will still leave a lot for each individual practice to figure out,” says Dr. Hardten. “It will be based on our patient populations, the capacity of local hospitals, the patient demographics, the intensity of the eye-care needs of the practice and staff/provider challenges. Even though we have a strategy for inching forward as a practice, we’re going to need to re-evaluate that strategy daily and make many changes in the next several months.”

Marguerite McDonald, MD, FACS, a practitioner at OCLI Vision in the Long Island, New York, area, says, “Recent federal guidelines for the country’s controlled re-opening have given all of us a glimmer of hope. But just a glimmer.”

Peter Netland, MD, Vernah Scott Moyston Professor and ophthalmology department chair at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, says ophthalmology’s sharp reduction in patient volume is “partly because we’re receiving mandates to reduce patient care from states, other government agencies and medical societies, and partly because patients are electing to hold off on routine care until this settles down.

“Comprehensive ophthalmologists are losing their patient volume; so are subspecialty care doctors,” Dr. Netland adds. “I’d say the average academic practice is probably losing two-thirds of its volume, in both clinics and the OR.”

|

| gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 |

“No Guidelines for This”

“This continuing situation we find ourselves in obviously changes and reduces our workload and increases our concern when we’re in the environment, considering our risk of bringing an infection back to our loved ones when we go home,” says Dr. Hardten. “You’re counting on the people around you to be vigilant and to protect the patients and you. There are no guidelines for this. It’s almost like we need to develop new eye-care triage guidelines in short order to replace those eye-care guidelines based on more than 30 years of comparisons and discussions about when it’s right to remove a cataract, or when someone is healthy enough for anesthesia and many other considerations. We’re basing our decisions on a new normal in terms of patient health, accessibility to care and our ability to provide that care, and we’ve only done it for the past few weeks.”

Dr. Hardten notes that decisions may not be robust—or well thought out. “That’s what really concerns me,” he says. “Layered on top of our normal decision-making is our evaluation of whether patients’ issues are significant enough to bring them out into this potentially lethal environment to give them care. Should we expose these patients to staff in the office, or expose our staff to these patients, many of whom are at risk for [complications from] COVID-19? Or should we wait another day, week, month or 18 months for a new vaccine or unil when the vast majority of people in our community are immune to this virus? We’re faced with new questions with each patient on any given day, and we have to help patients make those decisions.”

Dr. Hardten identifies some classic scenarios:

• The 62-year-old woman with borderline glaucoma. “You changed her medication three months ago because her IOP was high,” he says. “How long should you wait before bringing her back?”

• A 53-year-old man who yanks on the cord of a gasoline-powered leaf blower and the cord slips from his grip and whips across his eye, rupturing the globe and leaving his lens hanging out. “You should probably have him come in, even though he’ll be at great risk because the virus is everywhere,” says Dr. Hardten.

• A patient has a pressure of 29 mmHg and a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.9 and is on maximal medicines. “Does he need that tube shunt now or do you wait?” asks Dr. Hardten. “And how long do you wait?”

• A patient is driving back and forth to work every day with 20/200 bilateral cataracts. “She shouldn’t be driving now,” he observes. “What would happen if you waited a month, two months or longer to bring her in? Is that really the best choice for her?”

He notes many gray areas lie between the obvious choices. “We’re prioritizing patient care in a way we’ve never had to prioritize it,” he says. “My advice is to think through these unusual scenarios and the questions you’re facing and adapt them to what will work for you. Because there’s no such thing as unusual anymore.”

Sticking by Your Staff

|

All ophthalmologists interviewed for this article agree: This is no time to deconstruct your most important infrastructure. Dr. Hardten and the others believe the real bricks and mortar of your practice are the people who make it hum. Without them, the patients won’t come.

“The work force we have is extremely well-trained and tuned into our business needs, so we want to keep them thriving throughout this ordeal,” he says. “We want them to be ready, willing and safe to come back to work when work is available. We’ve needed to furlough employees, but we’re working very hard to keep engaged with them in different ways. Their hearts are in the work that they do. That’s their passion.”

Alan Aker, MD, who runs Aker-Kasten Eye Center with his wife, Ann Kasten, MD, in Boca Raton, Florida, couldn’t agree more. He says their staff makes up a pillar of the practice that connects with the other pillar, loyal patients. Together, those two pillars keep the practice upright when threatened by the sudden ground shifts of negative change. Even when he was forced to close their clinic and ambulatory surgery center on March 13, Dr. Aker says he and Dr. Kasten committed to paying staff their salaries for 10 weeks.

“We value our staff and we’re thankful we had the ability to continue to pay them,” says Dr. Aker. “We explained we were concerned about the health of our elderly patients and all of our staff. Our instructions were for them to stay home as much as possible. A low number of our staff members came to work to contact patients whose surgery and clinic appointments were being canceled.”

Dr. Netland also seeks to protect his investment in people. He describes how his group has changed the way staff members work together. “We’re separating staff into smaller groups,” he explains. “We don’t want a situation in which everyone is rotating all the time with different people, because if one person turns out to be COVID-positive, we might have to quarantine a larger group of people.”

Bryan S. Lee, MD, JD, in private practice at Altos Eye Physicians in Los Altos, California, and an adjunct clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University, operates the Peninsula Eye Surgery Center with 14 other surgeons. Because Northern California was one of the first areas in the country to order sheltering-in-place, he and the others stopped performing surgeries in mid-March.

“My partners and I are doing our best to take care of our staff in the meantime,” says Dr. Lee. “They are so important to us, and I try to keep up to date on how they’re coping. I think the key is doing your best to take care of your employees. There’s no way to move forward without them. Take advantage of every program that allows you to conserve cash, such as deferring mortgage payments if your bank allows you to do so without penalty. Other than that, all we can do is try to stay safe, because nothing else matters if you’re not healthy.”

Economic Reality

The challenge of taking care of staff in these times, of course, is that your budget won’t support the expense if your revenue stream is running dry. Two loan programs offered under the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) that were designed to provide loans to private practices with fewer than 500 employees—the Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loan—ran out of funds two weeks after they were launched on April 4.

As Review was being printed, $310 billion in additional PPP funds and $60 billion in more EIDL funds were included in a $484 billion coronavirus relief package that was being signed into law. Although the PPP and EIDL target the payroll expenses of small businesses, the PPP has been the most coveted because eligible recipients may qualify for a loan of up to $10 million, determined by eight weeks of prior average payroll (capped at $100,000 per employee) plus an additional 25 percent of that amount for additional costs, such as utilities and rent. If you maintain your workforce, the U.S. Treasury Department will forgive the portion of the loan proceeds that are used to cover the first eight weeks of payroll and the 25 percent of additional expenses following loan origination.

Complete details on coronavirus relief options can be found at a user-friendly SBA website: sba.gov/funding-programs/loans/coronavirus-relief-options.

Another source of relief is the expanded advanced and accelerated payments for Medicare Part A providers. Within seven days, an application to this program will provide you with up to 100 percent of your claims amount for the previous 180 days. The disadvantage of this program, though, is that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin recoupment of what it’s paid to you by withholding payments on your future claims between 180 and 210 days, when the full amount owed must be repaid.

“This program will provide quick access to funds when you need the money,” says Dr. Hardten, the only ophthalmologist interviewed who was using the program. “At some point, your income won’t be coming in fast enough for you to earn net revenue while Medicare withholds every advanced and accelerated claim you’ve received during the the first 90 days of this program. Remember that the advance/accelerated claims will equal the normal amount of claims you were paid during the 180 days before the pandemic struck. So you’ll have a gap in your income, because you won’t be doing the same number of procedures you’ve already been paid for when you’re filing new claims during those initial 90 days of the advance/accelerated program. To fill that gap, you have to establish an alternative, longer-term funding source or line of credit.”

|

Challenging Your Budget

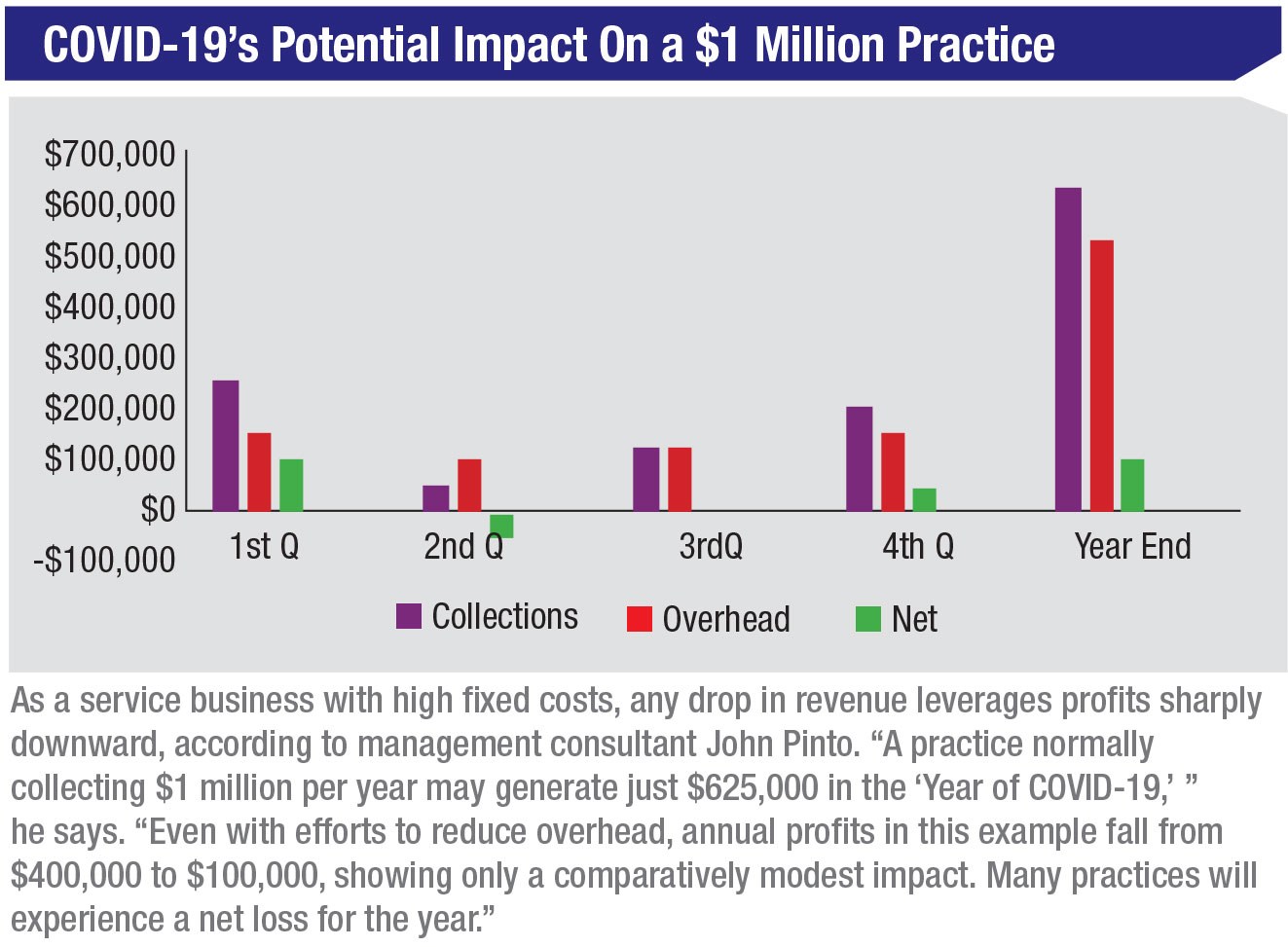

John Pinto, a national practice management expert with more than 40 years of experience helping practices manage cash flow and risk, says that the reduced revenues he expects because of the COVID-19 pandemic could be devastating to a practice that’s relying only on income earned in 2020 to stay afloat.

“When you’re in a business crisis like this, the crisis is only damaging to you to the extent that you do or don’t have access to capital,” says Pinto. “Let’s look at a simple example. The doctor with a solo practice has a terrible skiing accident that puts him on his back for three months. If the practice doesn’t have either insurance money or money in the bank to keep the practice alive for those three months, then the practice is going to go away. If the doctor has $2 million in the bank, then it doesn’t matter if it’s a three-month injury or a two-year injury. The practice is going to be able to come back. It’s the same thing with the COVID-19 pandemic, which is the biggest business crisis most ophthalmologists will ever experience.” (See “COVID-19’s Potential Impact on a $1 Million Practice,” below, which Pinto helped Review develop.)

|

Waiting for Rain

Most ophthalmologists expect a crushing overflow of patients once the environment becomes safe enough for them to seek delayed cataract surgeries and other procedures.

“Once the crisis has passed, catching up with the backlog of patients could be a logistical challenge,” says Dr. Netland. “If this goes on much longer, we’ll have to reschedule 10,000 to 15,000 outpatient clinic visits, and we have a large number of ‘elective surgery’ cases that we need to reschedule. How we handle the recovery will depend on the final number. We’re thinking about holding clinics on Saturdays and evenings, if necessary. Also, we’ll need to add surgery time.”

But until that day comes, it may be like awaiting for a long-delayed rainy season while the crops wither in the fields. Dr. McDonald, whose OCLI Vision practice is part of Spectrum Vision Partners, a four-state private equity practice, says her organization responded swiftly when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, furloughing her and all but a few clinicians at regional emergency centers. But she expects the practice to get back up to speed very slowly.

Practice planners wonder how many patients can be treated or receive surgery, given the need for COVID-19 precautions, social distancing, personal protective equipment, screening and other individualized attention that may reduce efficiency. In addition, many patients may not be eager to visit or have marginal cataracts removed until symptoms worsen, figuring they can ride out the pandemic. These factors, plus the bad economy, may suppress patient volume. “We may see a slow roll-out for all of those reasons,” says Dr. McDonald. “Eventually we’ll get there; then we’ll face a log jam from the backlog of cases.”

“Without sufficient patient volume to cover expenses, most practices can only go for a couple of months,” admits Dr. Netland. “Clearly, the longer a crisis like this continues, the harder it is to continue covering your expenses. As a result, furloughing or reducing hours is happening in most practices around us. Academic centers may be able to hold out a little longer; we’re a couple of weeks into this and we haven’t had to furlough yet. We’ve reduced hours to some extent, but we’ve tried to keep everyone employed. Clearly if things continue, we’ll have to adapt. We continue to evaluate this on a week-to-week basis.”

A Sound Plan

Drs. Aker and Kasten in Boca Raton plan to buck the trend. They hope to reopen their surgical center and clinic at the end of May—and possibly perform eight to 10 surgeries on the last Wednesday or Thursday of the month, pending local officials’ approval of elective procedures. He and his wife are examples of the surgeons John Pinto mentioned—those with protective capital reserves. Their resumption of operations will begin more than two months after they closed the eye center because they weren’t able to provide elective surgeries or care. During the layoff, they retained all of their employees on full-time salaries and continued their health-care benefits. Much of the time, those employees, mostly working from home, lined up patients for a surgical schedule that could get up to 15 patients a day—about 65 percent of their peak volume.

Dr. Aker says he’s also prepared for challenging financial times like these. “About 30 years ago, a financial advisor convinced me of the benefits of remaining debt-free. Since doing that we’ve always been very cash strong, with impressive balance sheets. No debt, no interest payments. As a result, we’re in a very good position to be able to ride this out and care for our patients and staff.”

Sooner or later, says Dr. Netland, reflecting on his many years in practice, others will join the ranks of Drs. Aker and Kasten as comprehensive ophthalmology recovers.

“One thing I’ve learned from living through pandemics such as AIDS, swine flu and others, is that this will pass eventually and things will get back to normal,” he notes. “How long that will take is impossible to say. But in the meantime, I feel positive about the flexibility and responsiveness of the health-care system in responding to this crisis. We’ve been able to shift things pretty quickly and mobilize. The crisis has revealed problems with our supply chains, and recovering from this will take time. But I’ve been impressed by how effectively people have responded.” REVIEW