There was a time when the only treatment for corneal edema we had was full-thickness corneal transplantation,” recalls Lorenzo Cervantes, MD, of Connecticut Eye Specialists in Shelton. In recent years, however, Descemet’s membrane epithelial keratoplasty has been taking over as the treatment of choice for many patients with corneal endothelial dysfunction. DMEK is an anatomical endothelium-to-endothelium transplant that requires less recovery time, achieves more predictable refractive outcomes and has lower rejection rates than other endothelial keratoplasty techniques. Here, experienced DMEK surgeons describe its benefits and explore emerging techniques that may soon make this beneficial but tricky procedure easier to perform and potentially suitable for more patients.

|

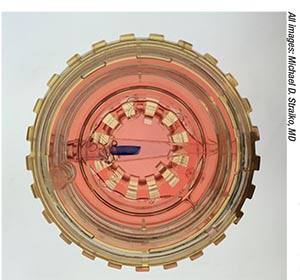

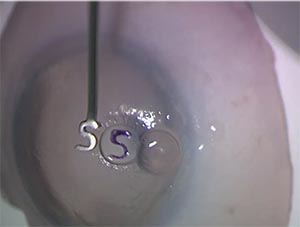

| View of a preloaded, stained DMEK graft inside the glass Straiko modified Jones tube. Preloaded donor tissue can dramatically reduce time in the OR for DMEK. |

“In many respects, going from full-thickness keratoplasty to DSEK was one of the biggest game changers in the world of cornea,” Dr. Cervantes continues. “DSEK was leaps and bounds better that fullthickness corneal transplantation or full-thickness keratoplasty. But DMEK has become more and more mainstream for several reasons. DSEK involves transplanting endothelium, but we’re also transplanting the posterior 20 percent of the donor cornea. With DMEK, there’s no stroma-to-stroma interface. That is leading to better-quality vision, and the recovery is even faster than after DSEK. A lot of my patients notice improved quality of vision by one to three months. The refractive results are much more predictable, to the point at which we can do DMEK together with advanced-technology IOL implantation. The rejection rates that we’re seeing are even lower than with DSEK: on the order of 1 to 2 percent over the course of a patient’s lifetime. For those reasons, I offered DMEK to my patients as soon as I was able to learn it.”

Preloaded Tissue

One of the original arguments against widespread DMEK adoption, according to Peter Veldman, MD, assistant professor, residency program director and vice chair for education, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science at the University of Chicago, was that the delicate and time-consuming nature of graft preparation made the procedure less efficient than DSAEK. “A few years back, many established DSEK surgeons would talk about how quickly they could do a DSAEK—in 10, 15, or 20 minutes—and they were hesitant to transition to a surgery that would take perhaps an hour in the surgery center to achieve results that were believed to be equivalent at that time,” he says. The advent of Descemet’s grafts from eye banks that are trephined to order, pre-punched, pre-stained, stamped with an orientation mark and then loaded into an injector tube has changed that. “I think it took an average of 15 minutes off of my cases when I made the transition to patientready DMEK,” Dr. Veldman estimates. He serves on the medical advisory committee (uncompensated) of Lions VisionGift eye bank in Portland, Oregon.

|

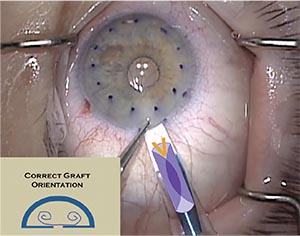

| A donor graft that is double scrolled, with both scrolls pointed upwards towards the stromal surface, is optimally placed for “dancing” the graft into proper position via external taps that take advantage of fluidics in the eye. |

Michael D. Straiko, MD, associate director of corneal services at Devers Eye Institute in Portland, and an associate medical director (uncompensated) at Portland’s Lions VisionGift eye bank, says that orientation marks on donor tissue help eliminate a major source of error in DMEK. “Because one of the main causes of primary graft failure can be an upside-down graft, having these grafts marked with an ‘S’ or an ‘F’ or some other kind of really intuitive mark helps avoid that complication, which takes some of the fear out of it for the surgeon and increases the success rate,” he notes. “Our eye bank’s partners have taken it even one step further: Not only do they prepare the tissue, they measure the epithelial cell density and inspect it at the slit lamp after they measure it. Then they preload and pre-stain the graft so that it comes to you in the injector tube ready to be implanted into the patient.”

“Stamping is so helpful,” adds Dr. Cervantes, who is medical director (uncompensated) at Eversight eye bank in Connecticut. “We used to have to rely on the way that the graft unfolds under the microscope for orientation; this can be very difficult if your view is poor. The S-stamp really saves time and gives the surgeon confidence that what they’re doing is correct. The most common way of orienting the tissue is by the placement of an ‘S’ stamp, using a little printing-press stamp at the end of a handle dipped in gentian violet. They stamp the stromal side of the transplant with an ‘S’ so when you’re looking at it, if you see the letter ‘S,’ the graft is oriented correctly. But if you see the number ‘2,’ that means you’re upside down and you’ve got to flip the graft,” he explains.

Dr. Veldman says that F-stamping, in addition to S-stamping, is becoming commonplace. “You want a definitive orientation mark, like a stamp, done utilizing a validated technique that minimizes endothelial damage,” he says. “Having a definitive reference mark takes you over that last hurdle by eliminating the number-one cause of iatrogenic primary graft failure: putting a graft in upside down. I also think for sur geons looking to incorporate DMEK, eliminating that fear of putting the graft in upside down is a huge confidence booster. I’ve heard that countless times from colleagues.”

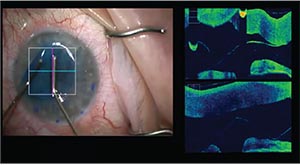

|

| Intraoperative OCT guidance can assist surgeons with decision making in real time and may reduce the risk of iatrogenic graft failure. |

Dr. Veldman adds that orientation marks aren’t just for beginning DMEK surgeons. “If you talk to any experienced DMEK surgeon, they will on occasion open up a graft that they believed was right side up, only to see that the ‘S’ or the ‘F’ is backwards. That’s happened to me many times. Once recognized, it’s quite easy then to flip the graft over to the proper orientation, preventing what would have otherwise certainly resulted in graft failure,” he says. “Published studies have shown that upsidedown graft implantation occurs up to 10 percent of the time—and although the actual incidence is likely significantly less than that as surgeons gain experience, it is still far from zero.”

“Preloaded tissue appeals to surgeons because the technicians who process those grafts do it all day, every day,” concurs Dr. Cervantes. “When Eversight began promoting their preloaded DMEK tissue, I was one of the first ones to adopt it. I was comfortable preparing my own tissue, but I’m only doing a certain number of DMEK transplant procedures a month, whereas they’re processing a lot of donor tissue every day. Our eye bank started offering preloaded tissue in the fall of 2017. In the fourth quarter of 2017, about 8 percent of DMEK tissue was preprocessed; in the first two quarters of 2018, 30 percent was pre-processed. In this third quarter, about 58 percent of our DMEK tissue is now preloaded.”

The rise of preloaded DMEK tissue brings attention to concerns about eye banks’ ability to select suitable donor tissue1 and to meet the Eye Bank Association of America’s requirements for post-processing assessments, however.2 “Though I’ve been using the preloaded tissue, that decision to adopt it isn’t universal,” notes Dr. Cervantes. “I know some surgeons who prefer to prepare their own tissue, and their reasons are valid. In preparing DMEK tissue, the surgeon has the opportunity to see if there’s been any endothelial cell damage prior to graft preparation. They can pick which part of the cornea they want to use. They might punch or prepare the tissue away from any areas of endothelial cell loss for improved quality. Perhaps the biggest reason not to use preloaded tissue, according to other surgeons, is probably the opportunity to assess the quality of the tissue before they prepare it and transplant it.”

“There are surgeons who prepare DMEK tissue themselves to varying degrees,” adds Dr. Veldman. “There is a billable code for tissue preparation in the OR [CPT code 65757]. For me, however, the time involved, as well as the risk of damaging the tissue, canceling a case and being out about $3,000 for a lost graft doesn’t stack up favorably against being able to bill for prep in the OR. Additionally, I feel very comfortable with the skillful tissue preparation techniques utilized by my partnering eye-bank technicians who do this for their profession.”

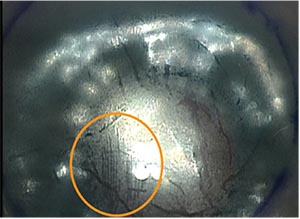

Drs. Veldman’s and Straiko’s preloaded DMEK tissue comes in Straiko modified Jones tubes (Gunther Weiss Scientific Glassblowing Co., Portland, Oregon). Dr. Straiko came up with the idea for this glass injector after ample trial and error. “We were using IOL cartridge-based injectors, and I used a whole lot of different types of injectors, some that I’d cobbled together in the OR. But sometimes the graft tissue sticks to the plastic, or the plunger can damage the graft. I’ve also occasionally noted striations in the endothelial-cell mosaic with plastic, where you can tell that the graft was actually scraped on the way out of the injector. I haven’t ever seen that with glass,” he says. “I was trying to come up with something that was glass, about the right size and shape and already FDA-approved. I came up with using Jones tubes because they met these criteria, and when I googled ‘Jones tubes,’ I found out that they’re actually made in Portland, not more than 15 miles from my office.” He contacted the manufacturer, and the Straiko modified Jones tube was developed.

“A lot of people use the Straiko modified Jones tube,” Dr. Cervantes notes. “It fits well through a 2.4-mm incision: This makes it very useful for when I combine DMEK with cataract surgery, which I can do through the same incision. There are other glass injectors that will work through even smaller incisions, but they might not be useful when you’re combining DMEK with cataract surgery.”

Practice Aids

Regardless of whether you prepare your own DMEK tissue or what type of injector you use, surgeons agree that it’s crucial to practice before attempting this tricky transplant on your own patients. Dr. Cervantes and Dr. Straiko recommend a modified artificial anterior chamber devised by Christopher Sáles, MD, to practice manipulating the graft.

“It’s a really good training tool that uses an artificial anterior chamber that’s been partitioned with a latex diaphragm. You put a corneal scleral cap on top, and then use that for practicing DMEK surgery, “ says Dr. Straiko, who was also an author on Dr. Sáles’ paper describing the practice model.3 Dr. Straiko adds that he just observed its use at the Cornea Society’s educational summit for fellows in September. “It worked really well for training young surgeons to do DMEK,” he reports.

|

| The circled area shows a region on a donor DMEK graft damaged by a plastic injector. Some surgeons think glass injectors are potentially less damaging to endothelial cells. |

“It works so much better than cadaveric eyes, which are what we used to use,” says Dr. Cervantes. “Cadaver eyes get mushy and soft, and their corneas become hazy and cloudy. They definitely don’t behave like eyes that are full of life. But these artificial-chamber eyes do behave like actual eyes. Dr. Sáles’ practice model uses an artificial chamber to create the same type of fluid dynamics that we encounter during actual DMEK surgery, and it has been very well received.”

Dr. Straiko adds that the artificial anterior chamber may give surgeons an edge prior to attempting DMEK on patients. “Although it’s a very realistic model, I find that the surgery on real patients is a little bit easier, just because of the way the iris behaves in the model. But it’s still much better than practicing on a cadaver eye or a pig eye,” he says. He also recommends teaming up with a seasoned DMEK surgeon for your early cases.

Patient Selection

Once you’re ready to perform your first DMEK cases, patient selection is key to early success, says Dr. Straiko. “The other tip for people just getting started is that they should really look for eyes that have a normal lens-iris diaphragm and a normal anterior chamber depth. Shallow anterior chambers are okay, but you want to avoid hyper-deep chambers or any special circumstances, such as iris defects, unstable lens implants or prior vitrectomies. Those eyes are just more difficult to operate on; you’ll want to pick up your earliest experiences with DMEK in relatively normal eyes.”

Dr. Cervantes adds that for all of DMEK’s potential benefits, there are some patients even experienced surgeons might want to offer other procedures. “There are instances where DMEK is not the best option,” he says. “For example, if a patient has a lot of corneal scarring in addition to corneal edema; a patient who has more complicated anterior segment anatomy due to the presence of glaucoma tubes or shunts; patients who’ve got anterior chamber intraocular lenses; patients who are aphakic; patients who’ve had a vitrectomy—these patients don’t make good DMEK candidates; their complex anatomy can interfere with the unscrolling and the unfolding of the DMEK graft. But a DSEK graft could do well in those eyes because it’s sturdier and easier to unfold inside the eye.”

DMEK Dancing

Dr. Cervantes says, “Universally, I think the hardest part of DMEK is learning how to unfold the graft. It’s unlike any other procedure that we do. It’s a series of tapping or corneal manipulations that creates fluid waves within the eye, affectionately known as the ‘DMEK dance,’ to unfold and move the graft around without directly touching it. There are all sorts of different techniques and nuances to it. It’s very difficult to explain verbally or by reading: It’s probably best learned by seeing surgeons do it, and by practicing it before attempting it with a live patient.”

Dr. Straiko reiterates the need to practice dancing the graft into place until you understand it intuitively. “I think it’s important to partner up with a surgeon who’s experienced, so you can get a feel for how hard you tap and where you tap. It’s not just random beating on the cornea: It’s really directed taps, used to direct fluid currents in the eye to dance the graft open and into position,” he explains.

|

| A gentian violet “S” or “F” stamp helps beginning and seasoned DMEK surgeons alike ensure that the donor graft is right side up. |

Dr. Veldman notes that managing unfolding of the graft warrants careful study. “When you’re learning DMEK early on and watching videos, it can just seem like a lot of tapping and cannulas flying around, and then suddenly, the graft is open. But really, if you break it down, an experienced surgeon is quickly recognizing what conformation the graft is in, and drawing upon their experience to choose a technique to open it. There are really only a handful of orientations a DMEK graft can be in once it’s in the eye. To be able to reliably and efficiently open a DMEK graft, you have to have a clear strategy for each possible orientation, quickly assessing whether it’s a simple fold, a double scroll or a single scroll, for example. What’s the most likely strategy to work? The second? The third? What’s the next conformation it’s likely to go into? You can really be almost algorithmic about opening grafts,” he says, adding that he recently spoke about standardizing one’s graft-opening technique at the American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting in Chicago.

Sulfur Hexafluoride

Once you get the graft into place, surgeons differ as to whether to use air or 20% sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) gas to make it stick. “Some surgeons do well using just air for the fill at the end of the procedure; whereas others feel that air alone might not be enough to keep the transplant stuck for long enough,” says Dr. Cervantes. “The SF6 stays in the eye longer and is safe for the transplant. But there’s debate on its use, and there’s variability in the rate of metabolism of the gas from patient to patient,” he says.

Dr. Straiko, who currently uses SF6 in all his cases, says that bubble size matters when it comes to optimizing DMEK outcomes. “It’s been reported by Friedrich Kruse’s group, and has been validated by other studies, that bigger bubbles are better,” he says. “You really want to have at least an 80-percent anterior chamber fill at the conclusion of the case to provide adequate graft support. There’s also data that indicates that using SF6 gas can decrease the risk of rebubble procedures and graft detachments.

“I like the pressure to be elevated to about 40 mmHg for approximately two minutes, then I restore it to normal physiologic intraocular pressure,” Dr. Straiko continues. “If I’m leaving a patient phakic, I want to avoid high pressures, since that could cause cataracts. For most patients I make sure to never go above 40; for others, that’s not quite as critical. Obviously, if the patient has advanced glaucoma, you also want to avoid any high intraocular pressures, even transiently.”

Pull-through Techniques

Compared to other keratoplasty procedures, DMEK is still relatively novel; as surgeons master protocols and they become somewhat standardized, innovation also continues apace. Bimanual pull-through techniques may expand the indications for DMEK, according to Dr. Straiko and Dr. Veldman.

“Pull-through methods hold a lot of promise for more complicated eyes,” says Dr. Straiko, “including eyes with hardware from glaucoma surgery or anterior chamber IOLs, for example. Our standard DMEK techniques may not work or may cause too much damage to the graft in those patients. Pull-through techniques are a little more complicated because they rely on an anterior chamber maintainer, which can cause the fluidics in the eye to make the graft difficult to handle. But when they work, they can work very well, even in complicated eyes.”

As opposed to the push-through method technique using a glass tube or IOL-cartridge-based injector and no touching, pull-through DMEK requires the donor graft to be on a substrate of some kind that goes into the eye, and then comes back out without the graft, while the surgeon pulls the graft into place with forceps through a clear corneal incision. Dr. Straiko credits Massimo Busin, MD, with first reporting the use of a pull-through technique for graft insertion in DMEK, adding, “At Singapore National Eye Centre, Drs. Donald Tan and Jod Mehta have been working on modifiying the EndoGlide (Network Medical; N. Yorkshire, U.K.) for DMEK.” Dr. Tan developed the EndoGlide, a disposable plastic pull-through insertion aid; Dr. Busin has also been using the Busin glide for pull-through of corneal donor tissue for many years. Other conveyances include contact lenses or corneal lenticules. “Initially Dr. Tan was using the EndoGlide for putting a graft on a contact lens, or on a corneal lenticule,”says Dr. Straiko. “But now, they’re working on modifying it so that it doesn’t require any substrate: it just goes into the glide and the DMEK graft is pulled into the eye without any carrier tissue or contact lens.”

Dr. Straiko says that early data on various DMEK pull-through techniques suggest that they produce similar outcomes to standard DMEK techniques. “We’re currently working on a DMEK pull-through technique that we hope will make the procedure easier,” he says.

Because of the potential to use pull-through DMEK on more complex eyes, Dr. Straiko cautions about measuring pull-through outcomes against standard push-through DMEK with external tapping. “One caveat to keep in mind is to com pare pull-through DMEK to similar cases,” he emphasizes. “If you’re using pull-through DMEK for complex cases, you should expect higher complication rates and ECL rates just because of the nature of the eyes that get this technique done.”

Dr. Veldman also thinks that pullthrough DMEK may open the procedure to eyes that are poor candidates for injector-based DMEK techniques and external tapping of the cornea. “There are situations where standard DMEK is not your best procedure, for example, in eyes with prior vitrectomy or unicameral eyes. If you utilize a pull-through, where you have complete control of the graft, it may open up these indications,” he says. “One of the things I’m looking forward to is the further simplification of the pull-through techniques. One thing that’s on my timeline right now is to let the dust settle a little on the validation of the various pullthrough techniques, and then incorporate one into my practice for use in cases where a patient may be a lessthan-ideal candidate for my routine external-tapping techniques.”

In addition to pull-through DMEK techniques, some promising treatments for corneal endothelial decompensation are noninvasive alternatives to DMEK, Dr. Veldman notes. “Another interesting emerging option is Desecemet’s Stripping Only, and what implications that will have for the number of DMEKs we’re doing,” he says. “It’s certainly a very promising technique for the right patients, but I don’t think we know yet exactly who the right patients are. My impression is that the ideal candidate is likely to be an individual with a relatively small amount of central Fuchs’ disease.” He also notes the emergence of Rho kinase inhibitor eye drops as a potential treatment to heal the corneal endothelium.4 “This medication may prove a useful adjuvant for increasing the success and potentially expanding the indications for Descemet’s Stripping Only. That said, it is important to note that this is an-off label therapy at present,” he says. (For a discussion of these new techniques, see “The Newest Treatment Options for Fuchs’ ” on p. 38.)

Although new DMEK techniques and even alternatives to transplantation loom on the horizon, surgeons say that mastering the currently prevalent push-through technique is well worthwhile to give select patients the best visual outcomes possible right now. “It does require an investment of time and effort to master it, but it’s very worthwhile for the sake of your patients,” says Dr. Cervantes. Standardization is a double-edged sword, he adds. “I think that different parts of the procedure can be standardized to a degree, but they’re also very much guided by surgeon preference, and they’re also dependent on the individual patient’s eye. From the size of the eye to previous eye disease, to how fast they metabolize the gas that we use at the end of surgery, every case is going to be a little bit different. We’re all going to react to those factors differently as well.”

Dr. Cervantes, Dr. Veldman and Dr. Straiko report no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Straiko receives no remuneration or royalties for the Straiko modified Jones tube.

1. Vianna L MM, Stoeger CG, Galloway JD, et al. Risk factors for eye bank preparation failure of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty tissue. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:5:829–34.e2.

2. Eye Bank Association of America. 2016 Medical Standards. Washington, DC: Eye Bank Association of America; 2016.

3. Sáles CS, Straiko, MD, Fernandez AA, Odell K, et al. Partitioning an artificial anterior chamber with a latex diaphragm to stimulate anterior and posterior segment pressure dyanamics: The “DMEK practice stage,” where surgeons can rehearse the “DMEK dance.” Cornea 2018;37:2:26366.

4. Moloney G, et al. Descemetorhexis without grafting for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy– supplementation with topical ripasudil. Cornea 2017;36:642–48.