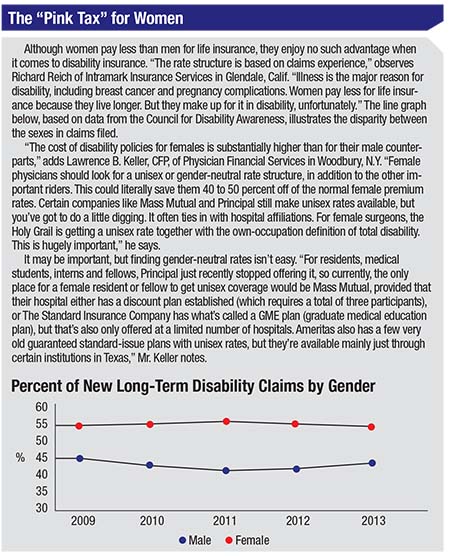

Although the last thing many people think about is the prospect of disability, it may be more real to ophthalmologists, who routinely bear witness to ocular injuries and pathologies that lead to permanent vision loss. The Council for Disability Awareness estimates that one in four 20-year-olds can expect to experience an episode of disability before retirement. To make matters worse, the organization adds that most Americans lack disability coverage and enough emergency savings to weather 34.6 months—the average duration of a disability claim (www.disabilitycanhappen.org).

In this article, seasoned insurance brokers with expertise in helping physicians choose the right disability coverage offer advice on what to look for and what to avoid when it comes to protecting your livelihood.

Hedge Your Bets

“Insurance is really legalized gambling,” acknowledges Lawrence B. Keller, CFP, founder of Physician Financial Services (http://www.physicianfinancialservices.com) headquartered in Woodbury, N.Y. But he stresses that it’s a gamble that surgeons can’t afford to forgo. “Disability insurance is something that anyone who’s working but has not yet achieved financial independence needs. You might love what you do, but you’re working because you need to generate an income. You need to protect that income, and the only effective way to do that is disability insurance,” he says.

Richard Reich of Intramark Insurance Services in Glendale, Calif. (https://www.protectyourincome.com), is a life and disability insurance specialist with an emphasis on insurance for physicians. Intramark estimates that policyholders should expect to pay 2 to 5 percent of their income toward disability premiums. “Here’s how I present it to people,” says Mr. Reich, “Would you rather have 90 percent of your income and be insured against disability, or would you rather keep 100 percent of it and take your chances?”

To clarify, there are other kinds of disability insurance that practice owners can buy for themselves and for critical employees, such as key-employee disability insurance; that is paid for by the business owner, who receives a payout if the key employee becomes disabled. The payout replaces business expenses and lost income occasioned by that employee’s absence from work. Our focus will be on personal disability insurance.

Because personal disability insurance is applicable to every practice setting and stage of life, our experts will explore its nuances and share the features they encourage their physician clients to look for.

Supplementing Group Coverage

Both experts note that as more young surgeons forgo solo practice, employer- and hospital-provided group disability plans have become prevalent. “Just 10 or 15 years ago there wasn’t a lot of group coverage, but many doctors—not just ophthalmologists—are joining groups now,” says Mr. Reich. “So we’re losing clients for their initial disability insurance in many cases. But we often help them pick up supplemental coverage.”

Personal disability coverage for doctors is a small market, Mr. Reich adds. “There are only a handful of companies that offer this

|

The relative stability of premium costs may mean little to cash-strapped residents and fellows. According to Mr. Reich, however, employer-provided group disability policies often have gaps that might need filling-in with more coverage. “In most cases, you cannot turn down group coverage. A major caveat in many group policies, however, is that the benefits are often taxable. If the group is paying the premiums, that is the key factor in the taxability of the benefits. If the employer pays the premium, then the benefit is taxable,” Mr. Reich explains. “I always recommend supplemental coverage, at least to recover on the taxability of group coverage. Most benefits pay 60 percent of your income. Let’s say you’re making $100,000, just to make it easy. You’re earning less than $10,000 a month and your benefit is 60 percent of that. You’ll be receiving less than $6,000 per month and that is taxable. So now your monthly net might be less than $3,000 after taxes. That’s probably not going to cut it, and that’s why they need to supplement it.”

Mr. Keller agrees, adding that you may need to supplement to make up for taxes and any earnings you have in excess of the “cap” on the group LTD plan, and because you also need some portable disability coverage. “If you’re working for a hospital and also doing some locum tenens work on the weekends, that work is self-employment income that has no coverage at all associated with it,” he says. “You’ll need to buy supplemental personal disability insurance.”

Whether you’re shopping for a disability policy that will supplement the policy your hospital or group offers, or you’re looking for your main policy, Mr. Keller and Mr. Reich say that a good disability policy has a number of important features.

Own-Occupation Coverage

For physicians, the strongest possible definition of total disability comes from policy language that is specific to their own occupation or even specialty. Mr. Keller and Mr. Reich emphasize that it’s well worth paying extra to get a more specific definition of disability than what’s in a standard “any-occupation” policy, which requires you to be disabled from all work/employment before you can collect. An occupation-specific definition of total disability will help make sure you receive benefits when you need them to replace lost income. Total-disability language varies between carriers, but should resemble something to the effect of, “You are unable to perform the material and substantial duties of your occupation or profession,” and not just employment in general.

“Make sure you get the own-occupation definition of disability, and make that specialty-specific,” urges Mr. Reich. “Some companies have very strong language when it comes to making a policy specialty-specific. If you can’t perform the duties of an

|

| The Centers for Disease Control has estimated that 22 percent of American adults have some type of disability. This estimate would subsume the number of workers suffering disabling illness or injury. |

“You want to make sure you have the own-occupation definition of disability,” Mr. Keller agrees. “At this point, there are only six companies that offer this to ophthalmologists, or any physicians: Berkshire Life (a Guardian company); Standard Insurance Company; Mass Mutual; Principal; Ameritas; and Ohio National—and the availability of this may vary by state and medical specialty.”

And, when you begin shopping for a policy, make sure it’s non-cancellable, experts say. “One of the first things to look for is a non-cancellable, guaranteed-renewal policy,” Mr. Keller avers. “Once you’re in, you’re in; and the insurance company can’t take it away or change the premium rates. You can get rid of them, but they can’t get rid of you. That gives you the most protection as a consumer.”

Association Policies

Mr. Keller notes that disability insurance provided through professional associations generally doesn’t offer own-occupation coverage, and such plans typically have less-liberal contractual provisions compared to individual disability policies. “The organization gets the master policy contract, and the individual gets a certificate essentially saying they’re part of this large group, but the individual members live and die by changes to the group. As with any policy you buy, make sure you do your research and understand what you’re buying before actually purchasing it,” he says.

Mr. Keller emphasizes that these association policies aren’t the same as individual policies issued with an association discount, which he unreservedly urges physicians to seek whenever possible.

Residual and Recovery Riders

“Residual riders offer partial disability if you can’t perform all of your duties, or if you can only work part time and have a loss of income as a result,” Mr. Reich explains. “You would receive a partial benefit, and the percentage of that benefit would be based on the percentage of lost income.”

Residual disability riders should never limit your eligibility for benefits to a return to work after a total disability. Mr. Keller explains, “Suppose you have a condition that flares periodically, and you don’t know what it is, but it forces you to miss work during flare-ups. You don’t know what’s going on, but you’re forced to work sporadic hours and see fewer patients and do fewer surgeries,” he says. “You might have a huge loss of income, but own-occupation coverage does not pay for loss of income alone, even in the best policies: After all, you’re still working very sporadically as an ophthalmologist, and so you’re not disabled from your specific occupation. You might have a huge loss of income, but your residual disability rider may stipulate that you can only get residual income upon a (restricted-duty or part-time) return to work after a period of total disability. Then suppose that three years later, your doctor says that it’s MS, and now and you’ve got to stop working altogether. You get zero for the three years that you worked sporadic hours because you were never totally disabled, and so never returned to work after a total disability. Most disabilities are sicknesses, not trauma; they’re gradual and might eventually become total. With the wrong residual-disability language in your plan, you can’t get anything for lost income if your disability progresses gradually before becoming total. At that point, you’ll only get your total, and then only after you meet your waiting period.”

In terms of protection, a recovery rider takes it even one step further, says Mr. Reich. “You don’t have to show a loss of time or a loss of duties,” he says. “You just have to show a loss of income as a result of having had a disability. So you could be working full time and doing everything you’d been doing before. But suppose you were out on full disability previously, and you’re just now returning to work. You’ll need to build your practice back up in many cases, which means you’ll still likely be suffering a loss of income during that time.”

Elimination Periods

Even if your disability claim is approved, you’re still on your own financially during the elimination or waiting period, which usually spans 90 or 180 days from date of onset. “Buying a rider that shortens your elimination period from 180 days to 90 days can make a huge difference by helping prevent you from selling off any of your assets to stay afloat,” says Mr. Keller. Although electing a 180-day elimination period can cut 10 percent off your premium payment, Mr. Keller urges ophthalmologists to consider how close they are to financial independence when choosing their waiting period.

“There are a lot of things that will take someone out of work for more than 90 days that will never make it to 180,” he cautions about the longer elimination period. “Later, from a risk-versus-reward standpoint, you may comfortably be able to extend the waiting period as you approach financial independence,” he adds.

Duration of Benefits

Make sure your policy will pay benefits for as long as possible. Some policies limit receipt of benefits to as little as two years. “They’ll usually last until at least 65 to 67 years of age,” says Mr. Reich. “But there are some that have lifetime benefits.”

If you have high earnings and are closing in on financial independence, both experts recommend keeping at least some coverage in place until age 65 or 67. “If you’ve already had good coverage and you’re earning good money, keep some coverage in place, if only to protect your assets,” advises Mr. Reich. If you want to save money on your premium, you can always modify the benefit amount, the elimination period, or some other feature of your policy to reduce your costs.

Future-Increase Option

Another key rider for younger, healthier surgeons is the future-increase option. “Ophthalmology residents and fellows at the very least should consider purchasing a tiny individual policy with a relatively small benefit now,” says Mr. Keller. “If you still have group insurance from your program, the individual policy will at least make up for some of the taxes you’d lose on group-plan benefits. Then, if you select a future-increase option, you could potentially increase the individual plan from $1,000 per month to perhaps $17,000 or more as your career progresses—without ever undergoing a medical exam, blood test, urine test or answering any additional medical questions, as long as you’re healthy at the time you purchase the policy.”

“Future-increase options allow you to purchase additional coverage as your income increases without having to go through medical underwriting again,” says Mr. Reich. “You just have to show proof of income.”

One caveat is to make sure your policy is amended—not replaced—when you purchase more coverage. “Some policies are going to give you a new policy that might have different terms than the original one when the increase option is exercised,” Mr. Keller cautions. “Others may just amend your existing policy. Clearly, an amendment to the existing policy is a safer bet than getting something new, because you just don’t know what’s going to change.”

Grab a COLA

If you accept the Council of Disability Awareness’ estimate that a disability claim lasts an average of 34.6 months, you’ll need your benefits to increase with inflation should the unthinkable happen. That’s where the cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) rider comes into play. “If you become disabled, the benefit will increase, typically between 3 or 6 percent annually for every year you’re disabled to help you keep up with inflation,” explains Mr. Reich.

Mr. Keller says that the COLA rider is well worth the extra premium costs for younger ophthalmologists. “This can be 10 to 15 percent of the cost of the policy,” he acknowledges. “But if you buy it as a 29-year-old resident or fellow, and your plan is to practice until 65, that rider’s really important because you’ve got a lot of time ahead of you,” he says.

Optional “Bells and Whistles”

“There are additional riders that I like, but these policies get very expensive when you start adding all the bells and whistles, so you balance what’s affordable with what makes financial sense for you,” says Mr. Reich. He adds that a personal disability policy with the riders enumerated thus far is very good. “If you want to make it even better, you can add a catastrophic rider, which would pay benefits if you have a catastrophic illness and then need assistance with daily living. You may also want an unemployment rider that will pay your premiums during your period of disability from work. There’s also a student-loan payment rider that will cover your loan debt.

“There’s another rider you can get that I like,” Mr. Reich continues. “If somebody becomes disabled and can no longer pay into their retirement account, there’s a rider that will contribute to retirement savings over the years.”

Insurance as a Map

While newly minted ophthalmologists may wonder how to swing paying for even basic individual disability insurance, Mr. Keller says that as little as $20 to $30 per month for a very small benefit early can become very powerful over time. “Your money is what pays the premium, but your health is what buys the insurance,” he notes.

“I don’t think anybody should go bare at any point,” says Mr. Reich. “Even if you’ve amassed a good amount of assets before you become disabled, you may need to dip into those assets and live off of them. I would rather somebody have some sort of policy in place so they won’t have to reduce their assets significantly to get through a disability.”

Both experts agree that you should re-evaluate your disability policy regularly, and consider making changes to move your coverage from earning-potential protection to asset protection over time. While something is always better than nothing where coverage is concerned, you can relax or eliminate some of your riders to reduce premium payments by getting rid of the COLA rider late in your career, for example. “If you bought your policy when you were young and healthy, and now you’re older and your plan is to not work a tremendous number of additional years, you might consider getting rid of the COLA rider because your claim duration is going to be much shorter than it would have been when you bought the policy,” Mr. Keller says. “If you’re now 55, and your plan is to retire at 60, how much value does that COLA rider really provide?” he says. “You might find that as you’re getting older, you can do a combination of things: remove the COLA rider; increase your elimination period; and potentially even reduce the monthly benefit. Your expenses are probably lower now; your kids’ college educations are perhaps funded; you likely own your home so there’s no mortgage. You simply don’t need what you originally did,” he says.

Mr. Keller says that it’s helpful to view disability insurance as a map. “It’s really just designed to protect you as you move from point A, where you have a lot of education, training and income potential, but no money, to point B, where you’ve converted all that into a high net worth. Do you really need it after many years? If you do, there’s a very good chance that you don’t need it in the same way that you did when you first started.”

Mr. Reich emphasizes that you can adjust this disability-coverage map incrementally and move to a less aggressive, asset-protection approach. “You can make a lot of changes to your policy without underwriting,” he says. “You can easily reduce the benefit, which I think is the most common way to reduce the cost among people I’ve worked with. You can lengthen the elimination period. Those are the two major steps, and you could also get rid of some of the riders that you don’t need anymore. That leaves you with more of a bare bones or catastrophic-type coverage that will prevent you from having to dip into your assets should something happen. At that point, it becomes more about asset protection than income protection.”

Something > Nothing

Mr. Keller and Mr. Reich emphasize the importance of getting disability insurance coverage in place as early as possible, ideally during residency or even at the tail end of your medical education. “Something is better than nothing, although many group plans are less than ideal,” Mr. Keller observes. If you want advice without pressure, he suggests checking in with a fee-only certified financial planner. “They’re not trying to sell you anything,” he says. “You’re just paying for their mind and whatever they tell you to do: Whether or not you choose to do it, their meter was running and they got paid for the ride.

“A good insurance rule of thumb is a corollary to ‘Don’t sweat the small stuff,’” he continues. “Don’t insure things that are not going to be financially devastating to you. Insure against financial catastrophe.”

When researched well and purchased wisely, disability insurance can protect your fundamental ability to keep your life moving forward if you’re unable to work. “I’ve seen people receive claims. I love the product because of what it can do for people,” Mr. Reich says. REVIEW

Mr. Reich is an independent broker. Mr. Keller has an affiliation with Guardian, but acts as a broker for all carriers without prejudice or bias.