It’s often said that death and taxes are inevitable, but today—if you’re an ophthalmologist—you might add “declining reimbursements” to that list. This economic reality has forced doctors to seek out new ways to generate income to keep their practices economically viable.

John S. Jarstad, MD, FAAO, a professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Morsani School of Medicine, University of South Florida-Tampa, recalls the first time he really felt the economic crunch, back in the 1990s, when Medicare quit paying physicians for a few months. “We had to scramble to come up with ideas to immediately generate cash flow,” he recalls. “Yes, we knew we could work harder and longer hours, but my office administrator suggested we try working smarter, by promoting options that could bring in more profitability while we did the same amount of work.”

Here, in that spirit, ophthalmologists offer some of the best ideas they’ve encountered for keeping a practice economically viable.

1. Make sure your facilities are always being used. To survive tough economic times, you need to make the most of your existing resources. That includes making sure the physical plant you work in continues to generate income nearly every day. In a large practice, that may not be a problem, but for a solo ophthalmologist it can be tough to manage. The simplest solution is to add either more partners to the practice or one or more optometrists.

“The bottom line is that your surgical patients originate from your office,” notes Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, founder and attending surgeon emeritus at Minnesota Eye Consultants in Bloomington, Minnesota. “If your office sees more patients—whether because you’re seeing more patients yourself, or because other doctors are seeing patients when you’re not in the office—you’ll have more surgery to do.”

|

|

Adding optometrists to your practice can ensure that facilities are always in use, free you to do more surgery and be a significant source of referrals. Image courtesy of Bradley A. Frederickson, OD. |

Dr. Lindstrom suggests that, based on his experience, the ideal size for a small practice is four MDs, with two to four optometrists also on staff and a practice-owned ASC or in-office surgical suite. He explains the rationale for this arrangement: “With this practice configuration, one of the doctors can be in the OR every day, leaving two or three doctors working in the clinic all the time. That works even if one doctor is on vacation or away at a meeting, and you can have the doctors take turns attending meetings. This keeps all of your facilities in constant use, and everyone can take time off without disrupting the routine.

“Of course, you can go bigger,” he adds. “I currently have 29 doctor associates. But the sweet spot was when there were four of us.”

The other option, which many ophthalmologists have chosen, is to bring one or more optometrists into the practice. “At Durrie Vision we’ve always integrated ophthalmology and optometry, and it works very well,” says Daniel S. Durrie, founder of Durrie Vision in Overland Park, Kansas. “Our surgeons do the surgery and all of our own preop exams, but many postop exams and routine visits can be handled by the optometrists. They’re an integral part of the practice, and as we move along and the volume of cataract surgery goes up, I think adding optometric services—under the direction of a physician—makes a lot of sense.”

Dr. Jarstad recounts that when he started out as a solo practitioner, he hired Bradley A. Frederickson, OD, to help him keep his office open more hours than he could manage while he was transitioning from academia to private practice. Eventually, he and Dr. Frederickson were managing the practice full time. “Dr. Frederickson had completed a one-year ‘fellowship’ with a cataract and refractive surgeon, and had exceptional clinical and people skills,” he recalls. “It quickly became clear that he was excellent at performing screenings and medical eye exams, and that took quite a load off of my incredibly busy schedule.

When Washington State became one of the early states to allow optometrists prescribing privileges, Dr. Jarstad “expanded Dr. Frederickson’s scope of practice to include management of stable medical glaucoma patients, diabetic eye screenings, triage of patients with cornea abrasions and other eye injuries, as well as managing postop patients who had concerns when I was in our surgery center operating. Eventually, unless a patient specifically requested one of our surgeons, we triaged all new patients through Dr. Frederickson.

“We added a second optometrist as the practice grew, which added better immediate access for our patients and also added to our bottom line,” he notes. Dr Jarstad says that bringing in the right optometrists not only served his clinic’s patients but also relieved a significant amount of daily stress.

Dr. Frederickson, who has practiced at the Evergreen Eye Center for about 28 years, explains that the optometrists in the practice maximize opportunity costs for the surgeons by managing all non-surgical ocular pathology. “Having a well-trained OD manage these patients frees up the surgeon to concentrate on surgical cases,” he notes, “while generating new patients for the surgeon to treat.

“The other alternative is to have an optical in the practice that offers routine eye exams, glasses and contact lenses,” he continues. “We don’t offer routine eye exams or sell glasses in our practice, but I know some ODs work in large ophthalmological clinics and generate revenue through the practice’s optical department, offering routine exams and so forth. They increase the practice’s patient base and can generate referrals within the practice.”

In terms of hiring an optometrist, Dr. Frederickson notes that not every optometrist will have the skillset a surgical practice may need. “If you’re going to have the optometrist manage medical issues and postop care, you want to hire a residency-trained OD, or someone who’s making a lateral move from another similar practice,” he says. “You want someone who’s ready to hit the ground running, able to handle all nonsurgical pathology—identification, diagnosis, proper referral to tertiary care, etc. Everyone learns as they go, of course, and every practice will have its own in-house technology and outcomes. But a residency-trained OD is more likely to be ready to deal with medical and surgical patients. That person can be a real asset to the practice.”

|

|

A baseline widefield retinal photograph, paid for by the patient, may uncover retinal issues. Image courtesy of James J. Salz, MD. |

2. Offer new patients a baseline widefield retinal photo. James J. Salz, MD, in private practice and a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Southern California Los Angeles, offers widefield retinal photos to all new patients, as both a retina screening test and a baseline for future comparisons. He says it’s beneficial for the patient and a good source of income for the practice—and he notes that most patients are happy to participate.

Dr. Salz explains that patients pay out of pocket to have the photo taken and reviewed by the doctor. “Medicare and insurance companies pay for photographs of pathology such as a retinal hemorrhage, vein occlusion, optic atrophy or diabetic retinopathy,” he says. “However, insurance companies consider a photograph of a normal retina to be a screening examination, so patients have to pay for it themselves.

“We explain to the patient that we can take a digital photo of the eye that will be a useful permanent record of their retina,” he continues. “It’s a more thorough exam than we can do with other instruments, because it generates a digital image that allows us to zoom in and look more closely at areas of interest. However, we also explain that insurance doesn’t cover this because we’re not monitoring a known health problem. We charge the patient $75 to take and interpret the photo—the same amount we charge for a refraction, another noncovered service. Of course, each ophthalmologist can decide what to charge.

“The technician explains this option to the patient first,” Dr. Salz says. “Then, if the patient isn’t sure about whether it’s worth doing, I show them printed-out examples illustrating the kinds of problems such a photo can reveal, and explain why we think it’s an important thing to do. We can find signs of high blood pressure; we may find cholesterol deposits in the arteries; we can find choroidal nevi; we can find diabetic hemorrhages; and we can find early signs of macular degeneration. These would probably be missed on a routine exam, because on a routine exam there’s no magnification.”

Dr. Salz says that when explaining this to the patient, he uses the analogy of a physical exam done by their primary physician. “I point out that if they go to their medical doctor for a complete exam, it usually includes a chest X-ray, even if the patient has no complaint,” he says. “The only thing the doctor learns from most chest X-rays is that the patient has a normal-size heart and doesn’t have lung cancer. This is similar; we’re checking to make sure there’s nothing wrong with the patient’s retina, while creating a baseline for future comparisons. Of course, I tell the patient that when we take the picture, we don’t want to find anything! Patients are very happy if they find out that their retina is normal.”

Dr. Salz says that patients rarely choose not to have the picture taken. “I’d say 80 to 90 percent of the patients we present with this idea are happy to do it, and they pay for it on the day of the visit,” he notes. “The fact that the picture can be taken without touching the eye is an added benefit, especially during a pandemic. The patient signs a basic informed consent, which was suggested by one of the coding experts at the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

“Once the patient has signed the consent we usually have the technician take the picture,” he continues. “Both eyes can be photographed in about five minutes, without any need for bright lights or eye contact. Then, when the patient comes into the exam room to see the ophthalmologist, the picture is already loaded onto the computer. We have 24-inch flat-screen monitors in every exam room, so we can show the picture and go over the details with the patient. Patients love seeing their own retina. If the patient has a smartphone, we can also transfer the image to the phone for further perusal by the patient.”

But do these images actually help catch retinal problems? “We find something we didn’t expect to find in at least 30 percent of cases,” Dr. Salz says. “For example, in one patient we found a cholesterol plaque in an artery that we would have missed on a normal exam. We referred that patient to a vascular surgeon. The vascular doctor found that the patient had carotid artery disease and needed a surgical procedure to clean out the carotid artery. So taking this photo can sometimes be lifesaving.

“It’s true that a problem this serious only turns up maybe 5 percent of the time, but we often find something less dangerous that’s still important to know about for the health of the eye,” he continues. “For example, we commonly find something like fine drusen near the macula, a possible indicator that the patient could develop macular degeneration in the future. That’s serious, but not life-threatening. This is good for the patient, because the earlier we diagnose this, the earlier we can put patients on appropriate multivitamins.”

Dr. Salz says there are currently at least three companies selling an instrument capable of taking widefield retinal photos. “We own a Zeiss Clarus, which we find easy to use, but Optos and iCare also sell instruments that can do this—the Optomap and Eidon,” he points out. “They’re all priced in the neighborhood of $50,000 to $80,000. We’ve found that it’s an excellent investment; it pays for itself many times over via the income you generate. Not only can you use it for the patient-paid screening photos, you can use it in the care of diabetics, patients with macular degeneration and so forth, and those pictures are reimbursable. We paid off the cost of the camera within three years.

“If you’re not doing this, you’re missing a significant source of income, and it definitely benefits the patient,” he concludes. “You’re not just getting extra income for the practice, you’re providing better medical care by finding medical issues that you otherwise would have missed. And of course, if we do find something on the photo—let’s say we find a choroidal nevus on the retina—then the picture we take the following year will be covered by insurance, because now the patient has a known pathology.”

3. Consider sharing the ownership of an ASC. “Some doctors are fiercely independent and want to remain solo,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “That makes it almost impossible to make a profit owning an ASC, because an ASC is only financially feasible if it’s being used most of the time. To make an OR feasible, whether it’s in the office or in an ASC, requires at least 600 procedures a year. If you’re operating about 40 weeks a year, that’s 15 cases a week. To make an ASC really profitable takes about 1,000 cases a year. So if a typical ophthalmologist does 500 cases a year, the best way to make an ASC work is to have two doctors get together. If you have four doctors, the ASC can become the most lucrative thing in the practice. But if you’re working solo and doing 500 cases a year, you’ll have a hard time making money with your own ASC.

“On the other hand, you can work around this and remain solo by sharing in the ownership of an ASC that’s also used by other groups,” he says. “Howard Fine’s practice shared an ASC with three other independent groups practicing in the same building. This practice model can allow you to enjoy the financial benefits of an ASC without worrying about having enough procedure volume to make it economically feasible.

“If you’re interested in pursuing an ASC, you may be able to get useful information about how to proceed just by talking to a surgeon who owns one,” he adds. “Alternatively, the Outpatient Ophthalmic Surgery Society—OOSS—is a great source of information on that topic.”

4. Network with local optometrists to generate referrals. Actively marketing your surgical services to local optometrists can result in a reliable stream of referrals for surgery. Having one or more optometrists in your practice can help make this work.

Dr. Jarstad notes that Dr. Frederickson became an important liaison with other optometric providers. “He was instrumental in helping us break into optometric referrals for cataract and LASIK surgery,” notes Dr. Jarstad. “He assisted in gaining optometric CE credit for our EyeMD lecture series to our referring optometry base, culminating in more than 100 ODs in our referral network, leading to more than $1 million in yearly optometric referrals for surgeries and clinic visits. That became 8 percent of our total yearly clinic income.”

“If you also want referrals from outside ODs to maximize your surgical volume, the ODs in your practice can serve as facilitators between the surgeons and other optometrists in the community,” agrees Dr. Frederickson. “Essentially, you’re marketing your subspecialty to the ODs in your area. That’s likely to be the highest-volume generator for any ophthalmology practice.

“Getting outside referrals doesn’t mean less work for the optometrists in the practice, because a lot of the outside ODs don’t comanage,” Dr. Frederickson notes. “We actually have a two-tiered system. We have a co-management system, where the referring ODs want to manage their patients postoperatively, and are capable of doing so. I don’t really see those patients; the surgeons deal with them. But many ODs don’t want to comanage, so we’ll see their patients postop. They may just want to see the patient back for routine diabetic eye checks. We call that arrangement ‘shared care.’ Meanwhile, I see plenty of medical visits that are reimbursed by insurance; plus, I’m managing postoperative care and I’m a liaison for the ODs in our area.”

Dr. Frederickson explains how their referral network is developed and maintained. “All of us touch base with the local ODs and build relationships with them,” he notes. “We provide continuing education opportunities for local optometrists and provide help for their patients. Because of COVID, we now offer CE via Zoom, but we used to meet for dinners and have approved CE presentations that allowed the attendees to accumulate education credits, which they need. This is a great perk to offer if you want to attract and maintain referring ODs outside of your practice.

“Basically,” he concludes, “if you want to work with optometrists, you have to be OD-friendly and want their business. It’s a symbiotic relationship—a little like the relationship between a dentist and an oral surgeon. An oral surgeon may build relationships with lots of dentists in the area, who then send patients to him. Routine care goes back to the dentist.”

5. Consider setting up a surgical suite in your office. Dr. Durrie is the chairman of iOR Partners, a company dedicated to helping ophthalmologists set up an in-office surgical suite. “Moving surgical suites into the office is definitely a trend,” he says. “Our company now has more than 20 centers signed up. Some are doing retina and glaucoma or cornea; most do cataracts.

|

|

An in-office surgical suite may enhance revenue and increase your control over your schedule while benefiting patients, proponents say. Image courtesy of Daniel S. Durrie, MD. |

“I was involved in the trend of moving cataract surgery from the hospital to the ASC,” he continues. “That worked great for ophthalmologists. It gave doctors control of their schedule, and there was revenue to be made if you were owner or part-owner of the ASC. Point of service changes are a trend in other medical specialties as well; orthopedics and cardiology are also moving to ASCs instead of the hospital.

“The latest trend is to take this idea further, creating a surgical suite in your office,” he says. “The shift toward having an in-office surgical suite has been happening for more than 10 years, but it’s picked up momentum lately. The number of centers we’re working with has more than doubled this year.

“Moving your surgical suite into your office has multiple benefits,” he points out. “First, it gives you even more control over your schedule. Second, it creates greater efficiency because it uses your staff and your space. For example, the surgical volume for most of the doctors in our center who attended the recent ASCRS meeting actually went up; everyone was able to adjust their surgery schedules to make up for the time away. Third, the revenue that normally went to the ASC now goes to your practice. Fourth, patients love it. They come to the same parking lot, check in at the same front desk, see the same people and then get the surgery done. It makes it more like LASIK, which is done in the office.

“Fifth,” he continues, “it has the same level of safety; the surgeon, sterility and equipment are the same as they would be in an ASC or the hospital, and there’s published data confirming the safety of this option.1 Sixth, in-office suites often contain the most cutting-edge, up-to-date equipment, because the surgeon gets to choose the equipment. In addition, we’re working to make the end result as environmentally friendly as possible.

“Another advantage is that a practice can do this with a lower volume of cases than you would need in order to justify building an ASC,” he says. “To justify having an ASC you need several partners and a high case volume, but an in-office surgical suite works for surgeons doing in the range of 30 to 40 procedures per month. That would never be enough to make an ASC financially feasible.”

Dr. Lindstrom, who is on the board of iOR, agrees. “An in-office surgical suite provides an option for ophthalmologists who can’t afford to build an ASC or aren’t allowed to because of certificate-of-need laws,” he says. “Doing this allows ophthalmologists to participate on the facility side, and it’s more efficient and patient-friendly than most hospitals. In an office-based surgical suite, the ophthalmologist might be able to net $150 per cataract case. You could do better than that with an ASC, but the ASC costs a lot more to build and you need a higher volume to support it, and there are a lot more rules and regulations.”

Dr. Durrie adds that it can be hard to set up an in-office surgery center on your own. “People don’t know how to get accredited and paid, or how to train the staff,” he says. “So, an outside company can be valuable; it’s like having a management company run your ASC, except that the OR is in your office.”

6. Provide packaged preop cataract surgery medications. “This can help patients by saving them a trip to the pharmacy,” Dr. Durrie points out. “Right now most practices write prescriptions; then the patient goes to the pharmacy and gets the preop medications. However, you can have an outside company put the medications together in a package that’s either delivered to the patient’s home or to a pharmacy near the patient. The companies make sure that all state regulations are followed. It’s convenient for the patient, it ensures that the pharmacy won’t make substitutions, and there’s some potential revenue to be made.” Will this cost the patient more? “Not necessarily,” says Dr. Durrie. “In many cases it ends up costing the patients less than going to the pharmacy.”

As an example, one such company is Legrande Health (legrandehealth.com). According to its website, Legrande manages prior authorizations, finds the best prices and arranges delivery to the patient. The company claims that this reduces callbacks to your office by as much as 80 percent.

7. Do more premium surgery. Of course, this is an option most surgeons are well aware of. “There’s no question you can increase your revenue by doing more premium surgery—especially by treating presbyopia,” Dr. Durrie points out. “It’s true that you have to make some adjustments to your practice to do presbyopic surgery right. You have to have some marketing and sales training for your staff. You have to figure out the economics. You have to figure out how you’re going to do touchups. But the option is right there: You can definitely increase your revenue by doing this. The surveys all say that patients want it and are willing to pay for it, and it’s also an avenue that’s well-supported by our industry, because the vendors also make more money when they sell premium lenses. I think it’s the number one option if you need to increase practice revenue.

|

|

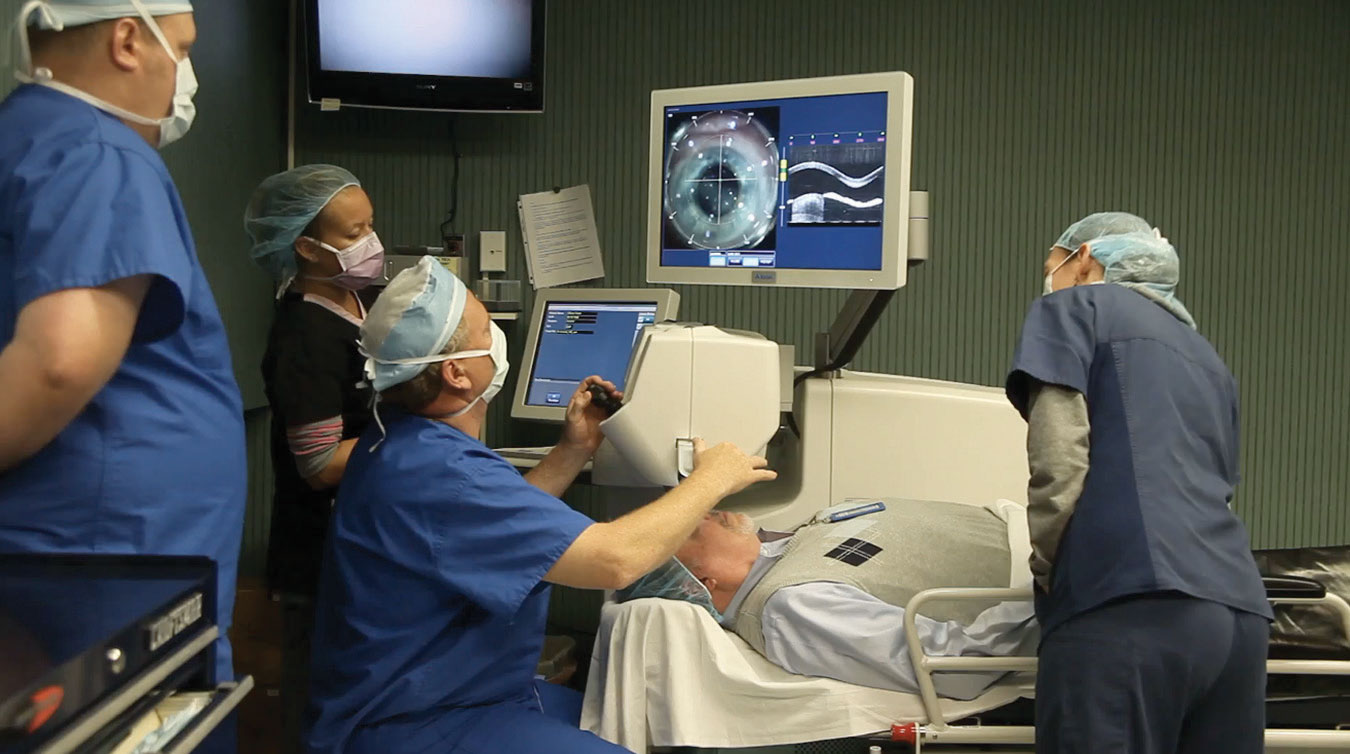

Offering premium options, whether presbyopia-correcting lenses or the use of a femtosecond laser, is a time-honored way to increase practice income. Image courtesy of John S. Jarstad, MD. |

“I hear lots of excuses from surgeons who aren’t doing this,” he continues. “Some say the IOLs aren’t good enough, but I don’t believe that’s true—if you hit the target. That means doing a little bit more work with your surgical planning and being able to do touchups, but today’s lens implants work very well, and they continue to get better. We’ve seen incremental improvements with each new lens introduced. I know that some surgeons are concerned that they may not hit the target; they feel more comfortable just doing standard cataract surgery, and that’s perfectly OK. But don’t blame it on the lenses, which have become quite good.

“Many times we fail to promote the advanced technology of premium IOLs and other procedures that our patients might benefit from because it takes a few minutes longer to explain their benefit and we’re running behind schedule,” notes Dr. Jarstad. “Sometimes we assume because of the patient’s appearance that they wouldn’t be interested or have the funds to purchase the premium technology products. I feel this is a mistake.

“In my early days as a cataract surgeon I recall a patient being a little upset and disappointed after her surgery because I hadn’t suggested the option of a multifocal or accommodating IOL,” he continues. “Many patients will ask family members to assist them financially or use financing when they truly want to be spectacle-independent. I remember a nice, elderly Korean-American lady with cataracts who was on public assistance but asked me about premium IOLs. It turned out that her grateful son was planning to assist her with the fees so she could have her dream of seeing without glasses following cataract surgery. Never judge a person by their appearance!”

Another option is charging to use a femtosecond laser during cataract surgery. “This is an economic opportunity that works well with premium offerings,” says Dr. Lindstrom. “The main use for a femtosecond laser in most practices is correcting astigmatism, and it’s clear that this isn’t being used to its full potential.

“It does require a certain volume of cases to make a femtosecond laser economically viable,” he continues. “The typical solo, comprehensive ophthalmologist can’t make it viable, although there are mobile services that a solo ophthalmologist can use. Being able to afford a femtosecond laser for use in your practice is another advantage of working in a group.”

Dr. Durrie points out another option along the same lines: offering refractive lens exchange, a.k.a. dysfunctional lens replacement. “Patients are willing to pay for lens replacement as a refractive procedure,” he notes. “They’re impressed to find that they can get rid of near- or farsightedness and astigmatism, improve their near vision and prevent cataract development.

“We need to move away from the term ‘clear lens extraction,’ because we’re not taking out a clear lens,” he adds. “The lens has nuclear sclerosis; it’s hard and can’t change focus. It’s a dysfunctional lens.”

8. Don’t undercharge for services. Dr. Salz points out that some practices undercharge—or don’t charge anything—for routine services that aren’t reimbursable by insurance. “Medicare and insurance don’t pay for a refraction, for example, no matter what the patient’s level of vision is,” he notes. “That means that patients pay out of pocket for this service, and the practice gets to decide what to charge. Many practices either have a very low fee for a refraction or don’t charge anything, and yet the refraction is every bit as important in an eye exam as measuring blood pressure is to an internist doing a complete physical.

“For a long time we were charging a minimal fee of $25 for a refraction,” he continues. “Today, if a new patient comes in, we typically bill the insurance for the medical exam and then charge $75 for the refraction, along with $75 for the optional retinal screening exam, which—as already noted—most patients are happy to pay for. That’s $150 on top of the medical exam reimbursement. When you consider that you’re seeing several new patients every day, that ends up being a significant amount of income.”

9. Expand your skillset and offerings. “American ophthalmologists aren’t doing as much minimally invasive glaucoma surgery, or MIGS, as studies suggest we could be doing,” notes Dr. Lindstrom. “Also, there are plenty of opportunities to treat dry eye.”

Another option is to bring in a surgeon with a specialty such as oculoplastics. Dr. Durrie points out that you need to have the right kind of patient base in order for something like adding oculoplastics to pay off. “If your practice offers private-pay refractive services like refractive cataract surgery, refractive lens exchange and ICLs, then oculoplastics makes a lot of sense,” he says. “Premium services tend to attract the type of private-pay patients that will be interested in oculoplastics, and your staff will know how to discuss payment options and explain the value of extra services. But if you take an oculoplastic surgeon and put him into a disease-based practice that doesn’t do any private pay, you won’t have the right kind of practice style for this to be successful.”

Dr. Durrie adds that he recommends bringing in an oculoplastic surgeon, rather than trying to add those skills to your own toolbox. “I think it makes sense for surgeons to stick with what they’re already good at,” he says. “Remember that we’re going to go from four million cataracts today to six million in 10 years. Cataract surgeons are going to be busy enough without trying to expand their skillset.”

Dr. Lindstrom says that if you’re a solo comprehensive ophthalmologist with a special interest in one area, and you’re looking at bringing in another doctor, it’s best to bring in someone who has a special interest in one of the other major sectors. “For example, if you were trying to create a maximally effective four-doctor group, it would be ideal to have one doctor’s subspecialty interest focused on cornea and refractive; one focused on glaucoma; one focused on plastics; and one focused on medical retina,” he says.

“If you don’t want to hire a partner, every one of these procedures is something a comprehensive ophthalmologist can be trained to do,” he points out. “If you believe one of these could be a good addition to your repertoire, you can start by reading and watching videos; then visit someone who does a lot of those procedures and observe. You can also ask them to mentor you.”

Physicians say you might also consider taking a business class. “This is a good time for ophthalmologists to be thinking about how to deal with declining reimbursement and increasing volume,” says Dr. Durrie. “Especially with private-pay options now looking more important to the bottom line, getting some business training can make a big difference.

“A few years ago I decided to take the ‘Physician CEO’ course at Kellogg Business School in Evanston, Illinois,” he says. “It’s specifically designed for physicians, and it was well worth taking. I learned a whole lot, even though I was successful in business before I took the class. I often found myself thinking, ‘Wow—I wish I’d known this 15 years ago.’

“The course is now in its seventh or eighth year, and everyone who takes it says it’s terrific,” he adds. “It’s only open to physicians, with about 35 people in a class. Many doctors say it was life-changing.”

10. Offer patient-pay alternatives to surgery. Another way to generate extra income is to offer medical alternatives to surgery. A new entry into this category is Upneeq (oxymetazoline hydrochloride 0.1%), an FDA-approved first-in-class eyedrop for patients with acquired blepharoptosis (also called “low-lying lids”). Essentially, it allows patients who appear somewhat sleepy to appear more awake and focused.

According to the company, a drop on the eye activates the alpha-adrenergic receptors in Müller’s muscle, stimulating contraction, resulting in elevation of the upper eyelids. One of several studies conducted by the company found that use of the drop increased upper eyelid elevation significantly more than vehicle in clinical trials, as measured by marginal reflex distance (the distance from the central pupillary light reflex to the central margin of the upper lid) on day 1 and day 14 of drop usage. Eyelid elevation was evident within five minutes of drop administration. The lid elevation even resulted in a statistically significant improvement in results on the Leicester peripheral field test.

The company says the drug’s safety is comparable to placebo. The most common adverse reactions are punctate keratitis, conjunctival hyperemia, dry eye, blurred vision, instillation site pain, eye irritation and headache, seen in 1 to 5 percent of patients; 2.2 percent of patients in the trials discontinued treatment due to an adverse event.

Kenneth J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, an associate professor of ophthalmology at the John A Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, and surgeon director at Fifth Avenue Eye Care and Surgery/Rosenthal Eye Surgery in New York City, says that he and several of his colleagues are offering Upneeq drops to patients with ptosis; he’s prescribed it for 30 or 40 patients so far. He sees it as trying medical therapy before resorting to surgery. “It stimulates the Müller’s muscle in the upper lid, raising it for about six hours,” he explains. “It keeps many patients with mild degrees of ptosis from needing to have surgery. We’ve used it with some success.” He notes that the company has announced the rollout of a program allowing doctors to sell the product from their practices. (He plans to participate.)

“It’s especially good for patients who aren’t good surgical candidates, either because their ptosis is mild, or because they have medical problems that preclude them from having surgery,” he adds. “I’m not aware of any failures, except for one patient whose ptosis was too severe. This allows us to say, ‘Well, we tried medical therapy first before going to the OR.’ ”

You can find out more about Upneeq at ecp.upneeq.com/what-upneeq-offers-your-patients.

Dr. Lindstrom is on the board of Minnesota Eye Consultants, UnifEYE Vision Partners and iOR Partners. Dr. Durrie is the chairman at iOR Partners. Drs. Salz, Jarstad, Rosenthal and Frederickson report no financial ties to any products discussed in their comments.

1. Ianchulev T, Litoff D, Ellinger D, et al. Office-based cataract surgery: Population health outcomes study of more than 21,000 cases in the United States. Ophthalmology 2016;123:4:723-28.