A history of prior uveitis can both hasten the development of cataracts and make cataract surgery more complicated. The cataractous changes of the crystalline lens are due to intraocular inflammation as well as the topical steroids that are used to treat the uveitis. Even with an anatomically successful cataract surgery, these patients are at a higher risk of postoperative complications, which could limit the recovery of vision.

Preoperative Planning

While uveitis can affect any part of the uveal tissue, from the front of the eye to the back, the most commonly encountered form is anterior uveitis, which is the focus of this article. And though there is a long list of potential causes of acute anterior uveitis, most often, we are unable to pinpoint the specific cause of the inflammation. When planning phacoemulsification, it is imperative that the uveitis is controlled and the eye is quiet prior to surgery. This means that for at least a few weeks, if not a few months, the anterior chamber should be free from cells. Often, it is nearly impossible to have complete resolution of the flare, so a minor degree of baseline flare is permissible.

To lessen the postoperative inflammatory response, these patients are started on topical steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs days to weeks prior to cataract surgery. These uveitic eyes are prone to a pronounced postoperative inflammatory response as well as complications such as cystoid macular edema. Subconjunctival, sub-Tenon’s or even intravitreal injections of steroids can be administered prior to surgery, though this is not commonly required. The use of systemic steroids or other immune-suppressive drugs is sometimes considered in particularly aggressive forms of uveitis.

Intraoperative Technique

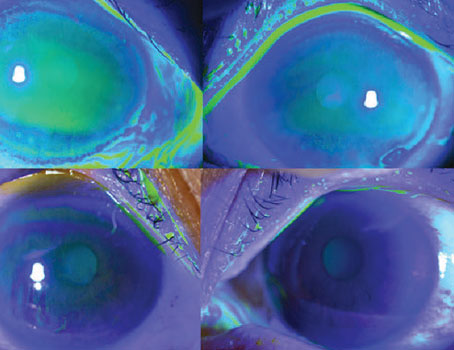

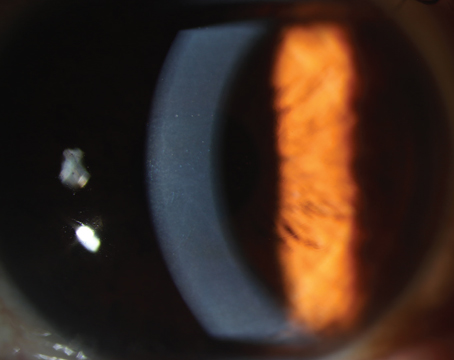

Many of these eyes with prior anterior uveitis have posterior synechiae with the iris adherent to the anterior lens capsule. The synechiae as well as any pupillary membrane can limit pupil dilation and limit access to the cataract. The membrane and synechiae can be dissected with forceps, a blunt spatula or even with viscoelastic solutions. The pupil can then be expanded mechanically and, if needed, held in position with iris hooks or other expansion devices.

A sufficiently large capsulorhexis of at least 5 mm in diameter should be made because the iris tends to adhere to the anterior lens capsule, which would lead to further synechiae formation in the postoperative period. While some surgeons advocate implanting a three-piece IOL in the sulcus in order to prevent the iris from contacting the anterior lens capsule, this may lead to iris chafe and further inflammatory issues. For most cases, traditional in-the-bag placement of the IOL is preferred.

For IOL selection, a monofocal lens design is recommended to maximize image quality, because spectacle independence tends not to be a priority in these eyes. The commonly used IOL materials are hydrophobic acrylic or silicone polymer, both of which have been shown to be reasonable choices, though some surgeons believe that acrylic tends to be quieter in the eye.

|

A recent study found that intracameral injections of triamcinolone acetonide and gentamicin are a promising treatment option for controlling postoperative inflammation after cataract surgery.1 This study included 60 patients who underwent phacoemulsification. Postoperatively, patients were randomized to receive either single intracameral injections of triamcinolone acetonide and gentamicin followed by topical tobramycin eye drops four times a day for one week, or topical dexamethasone-tobramycin combination eye drops four times daily until inflammation completely resolved. While no significant difference was observed between the treatment groups in anterior chamber cells at one day and one week after surgery, there were significantly fewer anterior chamber cells in the intracameral triamcinolone group than in the topical group one month after surgery.

In some cases, systemic steroids are administered as an intravenous infusion during surgery and are then continued orally in the postoperative period.

Postoperative Follow-up

The use of topical steroids and NSAIDs should be extended to ensure that the inflammation is completely controlled after surgery. While prednisolone acetate 1% ophthalmic suspension is commonly used after cataract surgery, stronger medications such as difluprednate 0.05% ophthalmic emulsion may be a better choice.

A recent study conducted in New York found that a high-dose, pulsed-therapy regimen of difluprednate 0.05% reduced inflammation more effectively than prednisolone acetate 1%, which resulted in a more rapid return of vision.2 Difluprednate was also found to be better at protecting the cornea and reducing macular thickening after cataract surgery. This study included 104 eyes of 52 patients who underwent bilateral phacoemulsification. One eye of each patient received difluprednate, and the fellow eye received prednisolone acetate. Eyes received seven doses during a two-hour period before surgery and three doses after surgery. Corticosteroids were administered every two hours for the rest of the day, then four times daily for the next week, and then twice daily for another week.

On day one, corneal thickness was 33 µm less in difluprednate-treated eyes, and more eyes in the difluprednate group were without corneal edema than eyes in the prednisolone acetate group. Uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuities were significantly better in the difluprednate-treated eyes than in the prednisolone acetate-treated eyes at day one. At day 30, endothelial cell density was 195.52 cells/mm2 higher in the difluprednate-treated eyes, and at day 15, retinal thickness was 7.74 µm less in difluprednate-treated eyes.

When discontinuing steroids, a slow taper should be used to prevent rebound inflammation. Because the long-term use of a topical ketone steroid, such as prednisolone acetate 1%, is associated with complications such as increased intraocular pressure, switching to an ester steroid like loteprednol 0.5%, which has less of a propensity to do so, may be advantageous.3 Continuing NSAIDs for at least six weeks may be helpful to prevent cystoid macular edema, which tends to occur more commonly in uveitic eyes undergoing cataract surgery. Serial optical coherence tomography measurements of the macula can be followed to watch for edema at the postoperative visits.

Once the eye has recovered from cataract surgery and the eye is free from inflammation, the patient should have a relatively routine postoperative course, though there is always the chance for a future recurrence of the uveitis. REVIEW

Dr. Devgan is in private practice at Devgan Eye Surgery in Los Angeles and Beverly Hills. He is also an associate clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and chief of ophthalmology at Olive View-UCLA Medical Center.

1. Simaroj P, Sinsawad P, Lekhanont K. Effects of intracameral triamcinolone and gentamicin injections following cataract surgery. J Med Assoc Thai 2011;94(7):819-825.

2. Donnenfeld ED, Holland EJ, Solomon KD, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled fellow eye trial of pulse-dosed difluprednate 0.05% versus prednisolone acetate 1% in cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152:609-617.

3. Controlled evaluation of loteprednol etabonate and prednisolone acetate in the treatment of acute anterior uveitis. Loteprednol Etabonate US Uveitis Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;127:537-544.