The young ophthalmologist had just signed a junior partnership agreement … then discovered the next day that her new practice was going to be sold to a private equity firm. Prospects of a long and prosperous career seemed to be swallowed in one gulp by the takeover, prompting her to abandon her new agreement ASAP. Elsewhere, an aging ophthalmologist worked hard for more than 40 years to build a robust practice … but he couldn’t find a younger doctor eager enough to take on the extra hours and weekend calls needed to eventually take over the lucrative concern.

|

Between these two extreme scenarios lies a gap between millennials and older practitioners created by myriad factors, including decreasing reimbursements, increasing regulations, future practice environment uncertainty and practice consolidation, as well as distinctly different lifestyles, work philosophies, networking behavior and methods of sharing clinical cases.

Although the gap is a reality, it’s also part myth and part misunderstanding. In this report, thought leaders lay out some key drivers of generational conflicts and suggest ideas that both sides may use to bridge the gap with new ways of working together.

Private Equity at the Gate

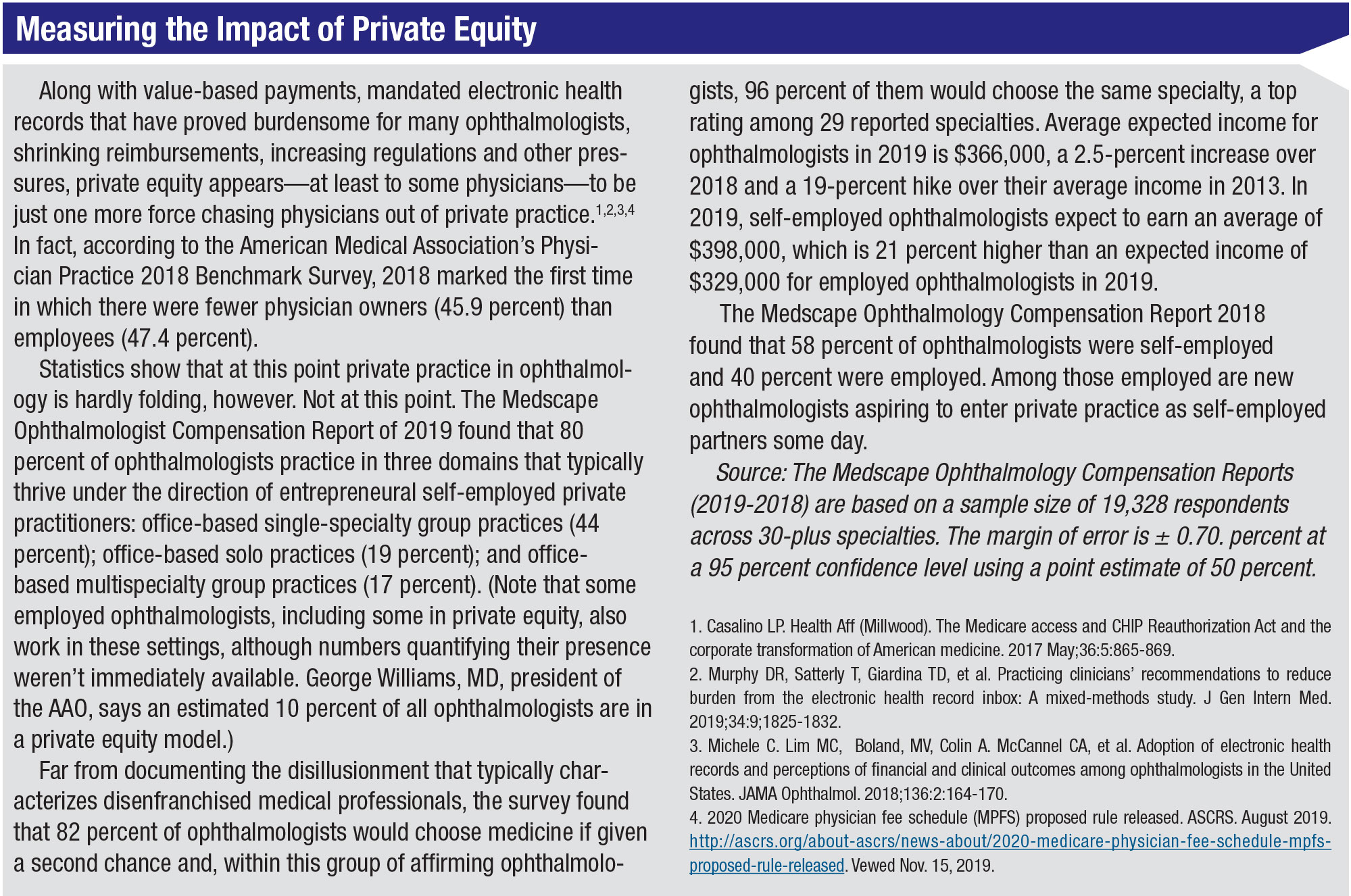

Possibly the deepest divide between millennials (practitioners ages 23 to 38 years old) and older ophthalmologists pertains to the growing private equity movement, driven by firms that purchase medical practices with capital from pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, high-net-worth investors and university endowments. The firms, anticipating average annual returns of 20 percent or more, typically acquire a platform practice, paying 8 to 12 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITA); then they expand by buying smaller practices at two to four times EBITA or less.1 The second phase of the purchase and development plan for the private equity firms is to streamline practice expenses, add revenue streams and resell the enlarged practices within three to seven years.2

Private equity firms, which focus on specialties that offer higher-income elective procedures, have concentrated primarily on dermatology, but their interest is now turning to ophthalmology, urology and gastroenterology.2 Some suggest that many firms are now exploring opportunities in ophthalmology, having become more active during the past couple of years. George Williams, MD, president of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, says an estimated 10 percent of ophthalmologists are now working in a private equity model.

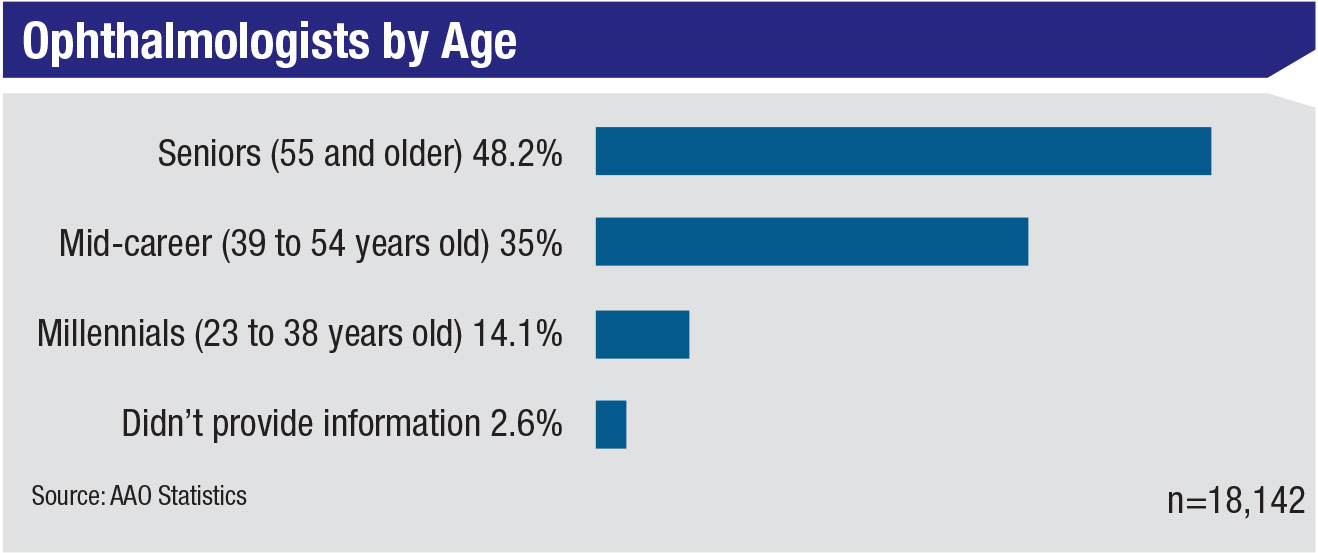

Although private equity firms are described by experts as diverse and motivated, in some cases, to use incentives to attract the interest of younger ophthalmologists, millennials are short on enthusiasm for the current offerings. This vocal group of young ophthalmologists now makes up 14 percent of the AAO’s membership.

|

“Private equity is the least favorable option for young ophthalmologists,” says Tom Harbin, MD, MBA, a published expert on the business side of medicine. “Under private equity, young ophthalmologists who aren’t partners will experience a lifetime of practice with reduced freedom and probably reduced income. As a young ophthalmologist, you typically won’t receive a payoff from the private equity group that is taking over your practice, nor will you share in the future growth of the equity or overall earnings of the practice. The young person who is not a partner will earn less money if he or she practices with a group that’s been purchased by a private equity group.

“Meanwhile, the physicians who are partners and sell their practice to a private equity firm receive a large upfront payment for the sale of their practice,” he says. “That large payoff is taxed as long-term capital gains, at a much lower rate than ordinary income tax. The partners usually give up income generated by practice profits forever and they earn much lower income as practitioners. The benefit for them, however, is that they pay an ordinary tax rate on their reduced income for their remaining years in practice. In this scenario, they usually come out way ahead because it takes years before you can be affected by a financial disadvantage from giving up that yearly revenue from your practice.”

|

Janice Law, MD, a retinal specialist at Vanderbilt and chair of the AAO Young Ophthalmologist (YO) Committee, says her peers worry about practice equity taking away future freedoms and opportunities. One of her friends, the millennial mentioned at the beginning of this article, had to hire an attorney to get out of her partnership agreement with the practice that was positioned for sale into private equity the day after she signed a partnership agreement with the group.

“The young ophthalmologist is very concerned about private equity,” she says. “At our YO meetings, any time that we talk about practice management and jobs in the context of contract negotiation, we always get a fellow or a graduating resident who has a very concerned look on his or her face. They come up to me or some of our other committee members asking for advice. ‘What should I do? The practice is talking to private equity. What should I put in my contract to protect myself?’ ”

Dr. Law offers this advice to the young doctors:

• Don’t be afraid to advocate for yourself. “Young ophthalmologists today are very transparent with each other about each other’s contracts,” she notes. “Young professionals today want to know the compensation for everyone in the organization, as much as possible. So ophthalmologists are asking each other, what did you get offered? What’s your buy-in? What’s this other person’s buy-in? They’re coming in more knowledgeable about what’s in their contracts. Of course, when you advocate for yourself, you need to prepare for resistance from the older generation. I’ve heard a lot of them say, ‘well, that’s how we’ve been doing it for 20 years. That contract’s not going to change.’ But it’s going to have to change.”

• Insist on a partnership agreement that will protect you. Dr. Law recommends language that will void the young ophthalmologist’s partnership contract in the event of a private equity purchase or other transaction that could end a young partner’s equity interest or restrict full revenue-earning potential once becoming a general partner.

|

“More young ophthalmologists—sometimes with the assistance of attorneys—are asking for clauses in their contracts that will free them from five- to 10-year commitments to a practice if these events occur,” she says. “They are also asking for non-compete clauses that will let them continue to practice in the same community if the contractual relationship should end for these reasons.”

• Consider an employment contract. If you’re not certain whether a practice will remain independent long into your future, you may want to start out as an employed ophthalmologist. “I don’t know exactly how many practices offer an employee track, but I do believe this would be an appealing option for someone who wants to learn the ropes without risk,” says Dr. Law.

What About the “Old Guys”?

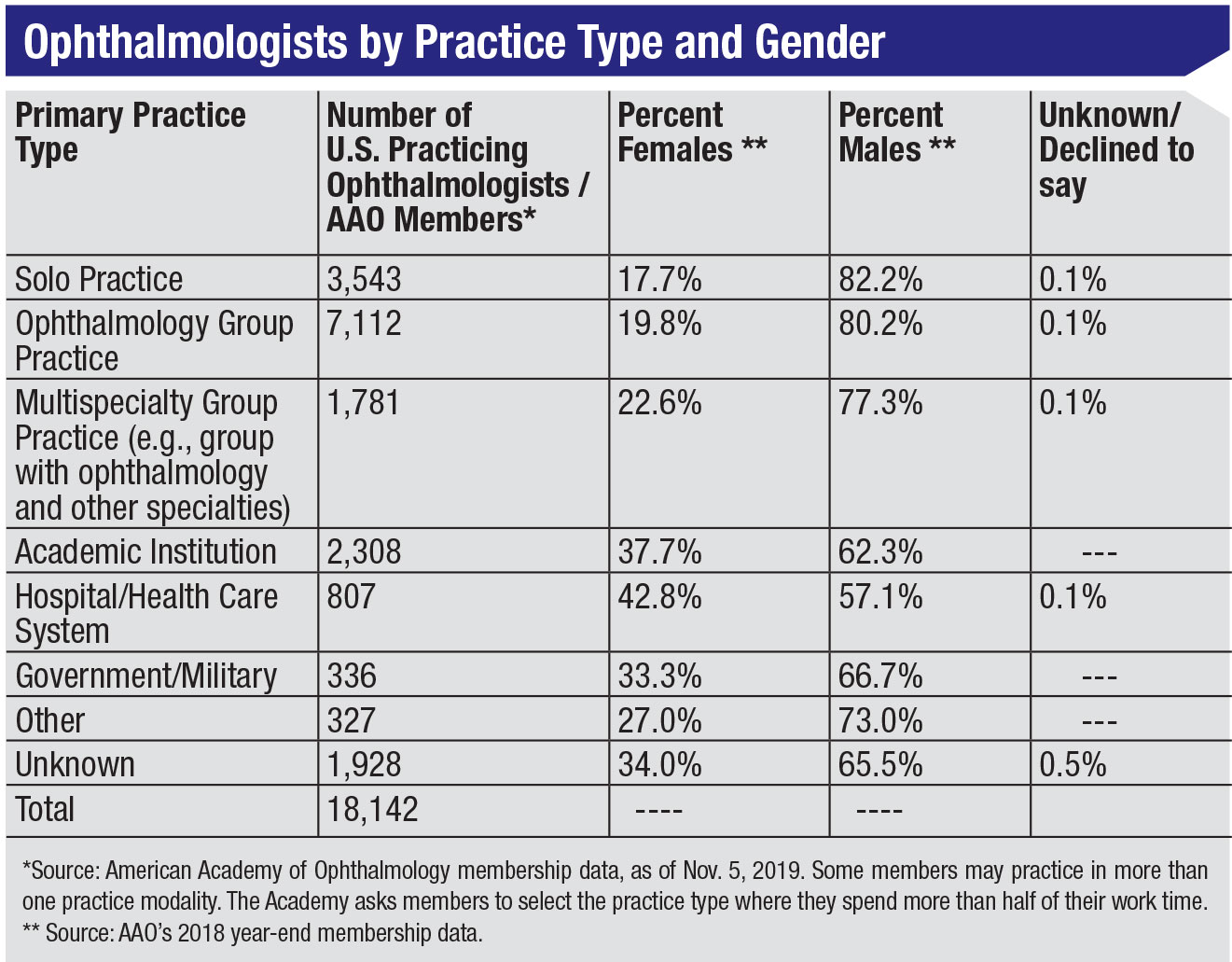

As much as young ophthalmologists fear getting cut off from the future opportunities and independence that their predecessors have always enjoyed, some older solo ophthalmologists are dealing with quite a different experience—an inability to sell their practices that didn’t afflict their retiring predecessors. This problem is only expected to get worse, now that the proportion of AAO members who are solo practitioners has dipped below 20 percent (3,543 out of 18,142 members).

“It’s happening because everybody is getting old,” says Dr. Harbin. More than 48 percent of AAO members are 55 and older, comprising the profession’s largest demographic by a significant margin. “They want to retire on their own terms and get a payoff for the many years of developing their practices,” he says.

|

While participating in a breakfast event on giving up surgery at the recent American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting, Dr. Harbin says a lot of older ophthalmologists were focused on retirement. “I can only speak in gross generalities—not based on any scientific example—but what I was hearing was that many millennials don’t want to assume the responsibility of running and managing a practice,” he says. “A lot of the older ophthalmologists in this category are in smaller towns. Twenty years ago, a younger ophthalmologist would come in and slowly but surely buy out the older ophthalmologists. Now, these older physicians can’t sell their offices.”

|

When millennial doctors visit their offices, the older physicians often learn that their practices don’t meet the younger doctors’ expectations. “What some of them hear is, ‘What’s my salary? How much vacation do I get? And I don’t want to do call.’ This is exactly what you don’t want to hear from a prospective junior partner. You want to hear somebody say, ‘I want to work hard and develop my practice, I’ll take call because that’s the way to get patients. How can I help?’ If your practice is part of a hospital system and you’re expected to take call, the call has to be covered. Saying you can’t cover call is not real world.”

Building Generational Bridges

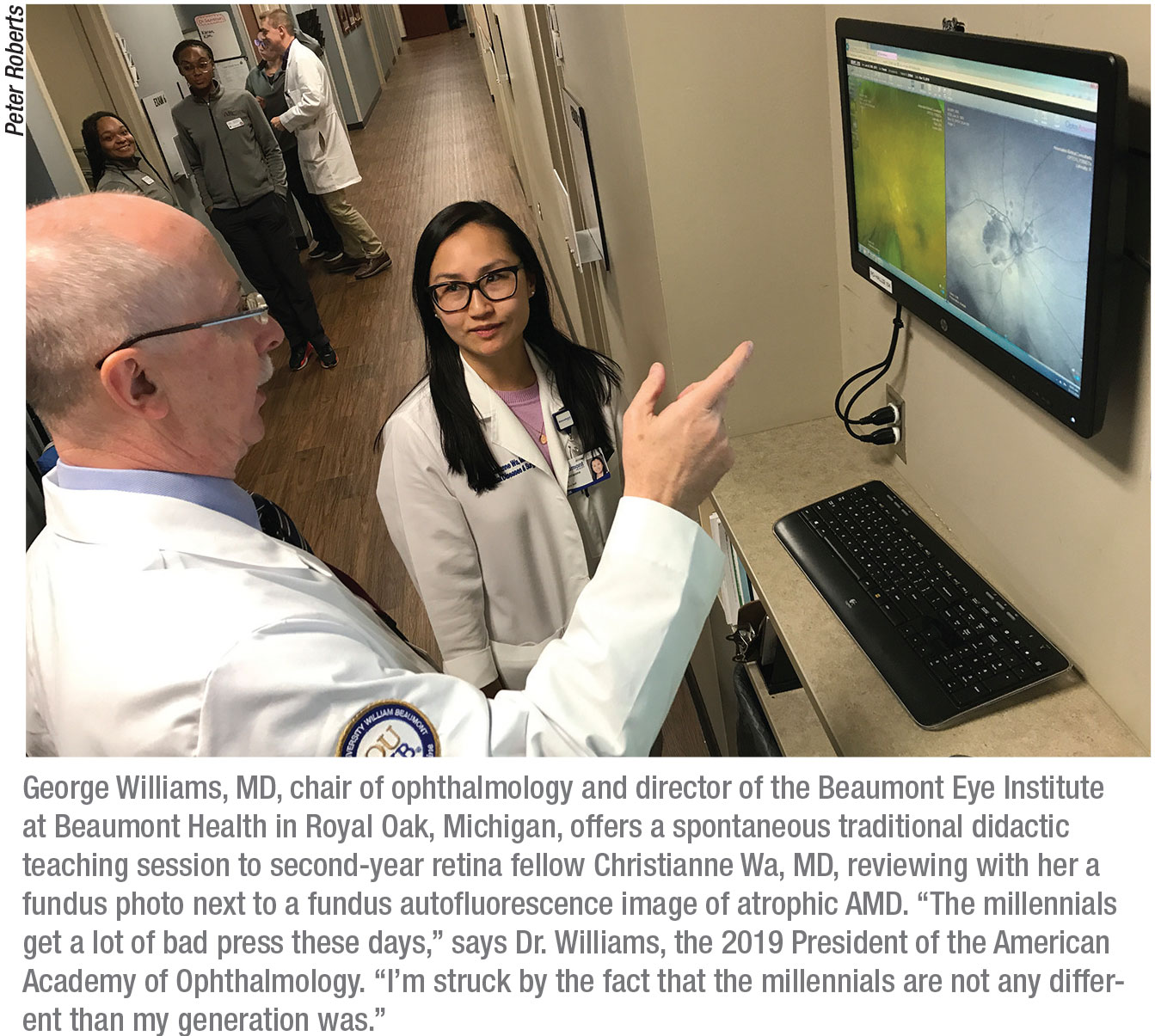

The increasing trend toward consolidation explains why many of these older physicians feel left out. Group practices continue to grow in ophthalmology, accounting for 39.5 percent of AAO members. “I have an old-guy perspective, but I have the data to back me up,” says Dr. Willliams, the current president of the AAO, with a polite tone. He is also chair of the department of ophthalmology and director of the Beaumont Eye Institute at Beaumont Health in Royal Oak, Michigan. “My old-guy perspective is also based on my perspective that the residents I train are less likely to go into independent solo practice. The Academy is now seeing a steady decline in members who describe themselves as solo practitioners and I fully expect that trend to continue. As far as the preferred model, that is going to depend on the individual. But increasingly the younger ophthalmologists we’re seeing have a proclivity to select the employment option in which they’re working for a larger entity, rather than going out and building their own practices.”

Young and old ophthalmologists alike agree that they need to build generational bridges to ensure a harmonious future, for both small and large practices.

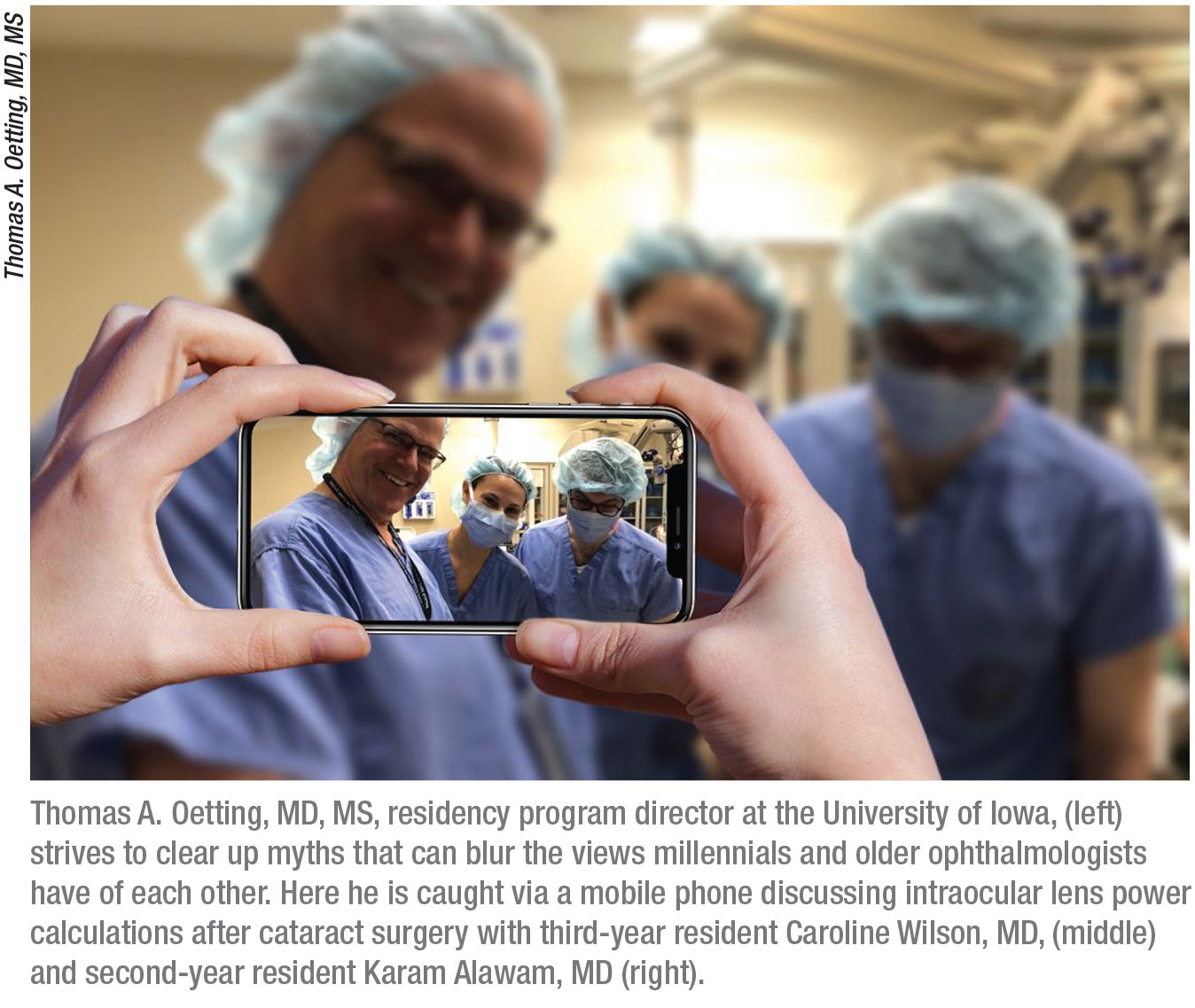

Thomas A. Oetting, MD, ophthalmology residency program director at the University of Iowa for the past 13 years, is described by residents and practicing physicians as one of those bridge-builders. More than anything, the 60-year-old preaches a practice-focused gospel of mutual respect. His advice to young ophthalmologists?

“Be useful and collegial,” he says. “Try to draw upon the great experience and wisdom of your senior partner. Some of a senior partner’s wisdom might be subtle or difficult to extract at first, and some of the skills millennials have may be difficult for the senior person to understand or appreciate. But the potential for a great marriage is there. I think the more useful the new person is, the more generous the older people will be. The more appreciative, encouraging and attentive the younger person is, the freer the senior person will be with the younger person.”

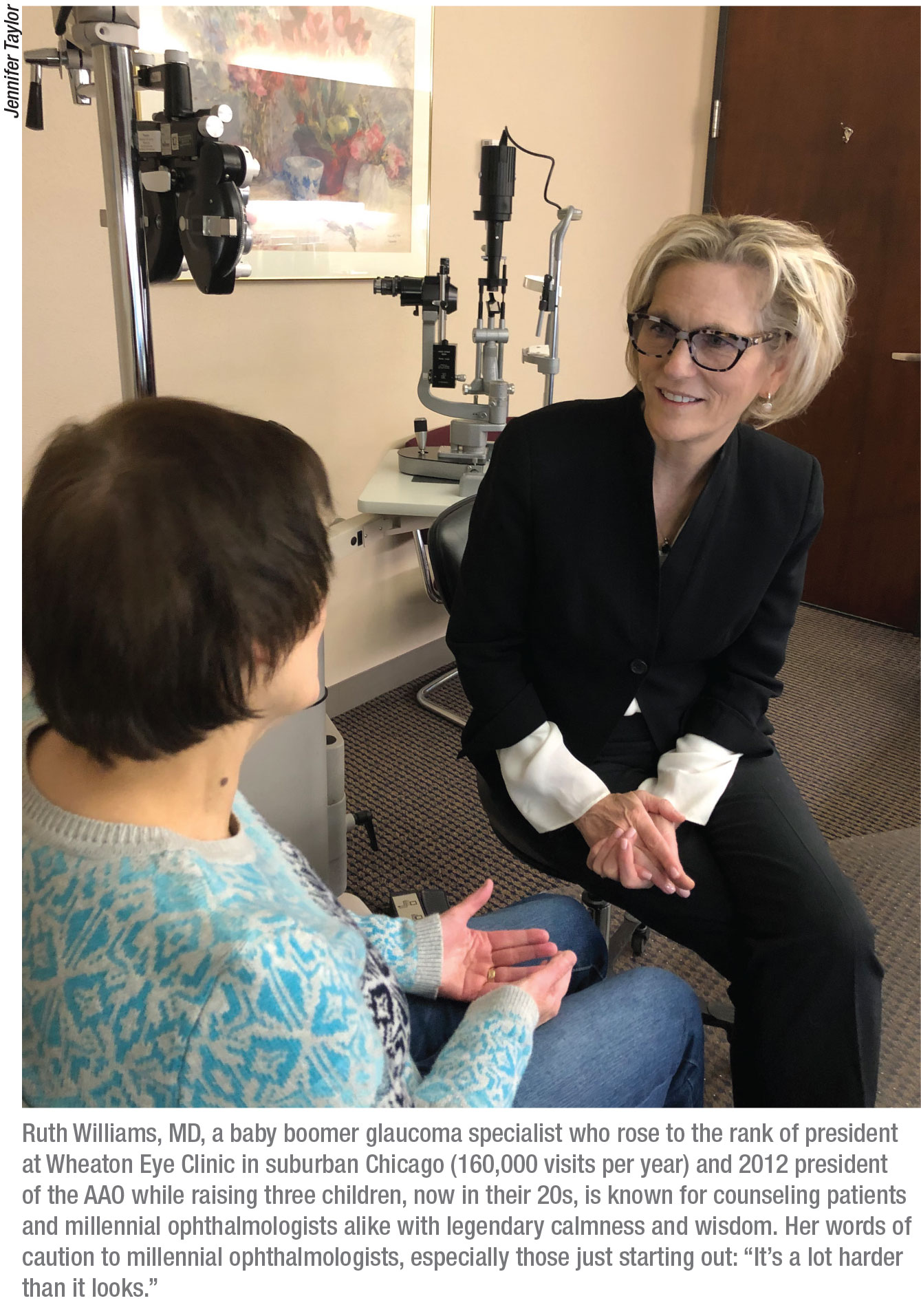

Ruth Williams, MD, a glaucoma specialist at Wheaton Eye Clinic in suburban Chicago, says she thinks many mid-career and older ophthalmologists have misconceptions about millennials. “They’re inheriting a different world than we inherited when we were their ages,” says Dr. Williams, a mother of three grown children who once served as president of her practice, which attracts 160,000 visits per year and involves the work of 33 ophthalmologists and 13 optometrists. She notes that baby boomer ophthalmologists, such as herself, complain that millennials don’t want to work as hard as the boomers have always worked. “That’s not so,” she observes. “They want to work. One thing that has changed is how we use time. We went home with pagers, but our hours were prescribed. Now, because of digital technologies, we’re available around the clock.”

Dr. Williams remembers one afternoon when she was managing a patient with orbital cellulitis. She called the cell phone of her young partner who specialized in oculoplastics and orbital surgery. “We worked through the complicated case on the phone,” recalls Dr. Williams. “When we were done, he informed me that he was on a ski slope in Utah. That’s one example of what happens all the time. I find that most young ophthalmologists are guided by a moral imperative to provide quality patient care and to help their colleagues when help is needed. They don’t regard it as an imposition. They are available.”

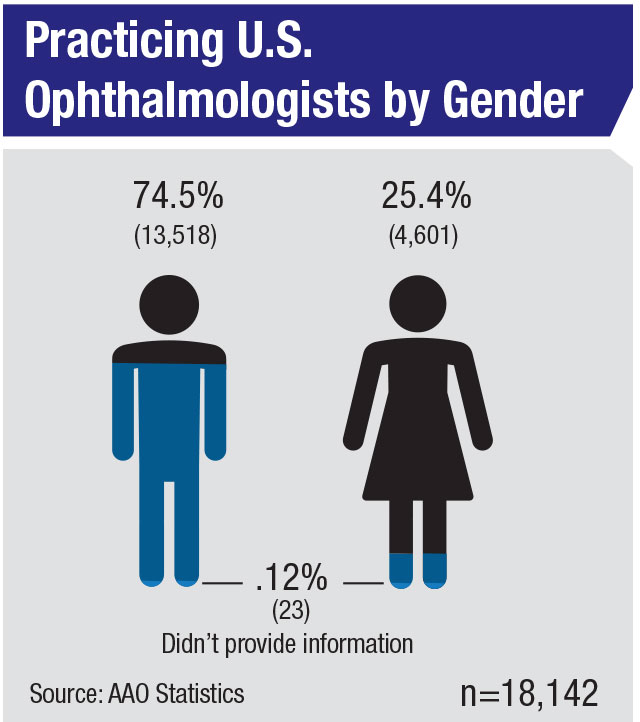

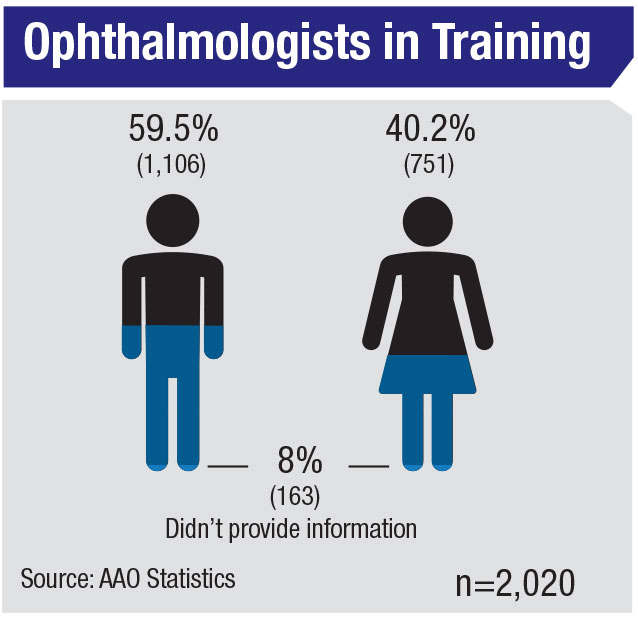

Dr. Williams, who also served as president of the AAO in 2012, notes that the needs of young ophthalmologists are changing. With the number of female ophthalmologists increasing (25.4 percent currently in practice and 40.2 percent in training), she observes that many of these women work extra hard to meet all of their responsibilities. “The young mom in ophthalmology is a serious professional,” she says. “She deals with the pull of meeting the objectives of the practice and the needs of her family. This is not just a gender issue, however. What I love about these younger people is that the men are also meeting the responsibilities at home—picking up the kids, going to the kids’ games. I think it’s wonderful. Workplaces that were once rigid are evolving.”

One suggestion she has for busy ophthalmologist parents is to allow them to work from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m. “This is perfect for picking the kids up after school,” she observes. “You can work a full day and be home by mid-afternoon. The baby boomer can work 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. And by the way, this schedule accommodates patients who need early morning or early evening appointments.” The challenge with this approach, she admits, is providing qualified staff to cover the expanded hours. “Innovative thinking will be needed,” she says. “The idea is to be flexible and for us boomers to respect diversity in the workplace. What worked for the baby boomer generation is not going to work for today’s young people.”

Purnima Patel, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Emory Eye Center and a former chair of the AAO YO Committee, agrees. She says potential friction points between new and older ophthalmologists are “deeply individual,” adding that “this is something we should be talking about and discussed openly, including an open commitment to physician wellness at all ages. Unfortunately, these issues are just not talked about. That was the culture until now. More conversation is needed—even in journals or publications. Everyone in ophthalmology, young or old, has a stake in this.”

|

Accepting Differences

Conversations with millennial, mid-career and older ophthalmologists yield other perceived and real differences among them, such as ideas about life/work balance, commitment to practice and the use of mobile-based crowdsourcing to share clinical challenges, negotiating strategies and advice for young parents on the go, such as favorite recipes. Meanwhile, the generation that was once known for shaking fists and shouting in protest against “the establishment” now finds itself at the head of another old-world order, contending with the quiet revolution of a fast-moving, digital-savvy generation that thinks and communicates differently. But many of the baby boomers, perhaps reminiscing on the deep changes they left in their wake, are learning to accept the new ways of this generation.

|

Dr. Oetting articulates an empathic message when describing the residents he’s mentored through the years at the University of Iowa: The difference between today’s young generation of ophthalmologists and those in the past is that, to some extent, today’s practice environment is less hopeful than when Dr. Oetting was a newly-minted practitioner. “For example,” he says, “practices are being bought by venture capital organizations, and we have uncertainty in future Medicare payment systems. There’s a sense that future revenue streams could be potentially harder to predict. Given that situation, you may be less able to commit to a big buy-in or to commit to some long-term relationship. Forty years ago in ophthalmology all you had to do was put up a shingle and you could make a fortune. It was really easy to start a career.”

Tamara Fountain, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and the 2020 president-elect of the AAO, expresses gratitude for the opportunity to lead these future leaders, as well all other colleagues in her profession, when she begins her tenure as president in 2021. “Thank goodness there are some [millennials] who go into medicine, because they want to effect a change in health care,” she says. “And we should applaud them. We’re getting young people who are coming through and wanting to be physicians in a climate in which the nature of how health care is delivered and paid for is very much uncertain.”

Dr. Williams, AAO’s current president, says millennials “get a lot of bad press these days. I’m particularly struck by the fact that millennials are not any different than my generation was. In ophthalmology, we attract a lot of bright people—I’d like to say the best of the best. I think millennials reflect this level of talent and enthusiasm. Perhaps they bring a little different perspective than some of the older folks had. But I’m not sure I can detect any significant difference.”

|

Strength Through Diversity

Repeating a point that both young and old ophthalmologists have made in interviews, Dr. Oetting observes that the millennials’ long-time familiarity with technology and social media differentiates them and makes them an asset to the profession. “They are much savvier and more knowledgeable about what’s going on in the world,” he says. “They’re more connected on issues such as what other practices are paying and what other people are doing than maybe I was when I came out. I might have had a few phone-call contacts, but the virtual network of mentors that our graduates have now is massive.”

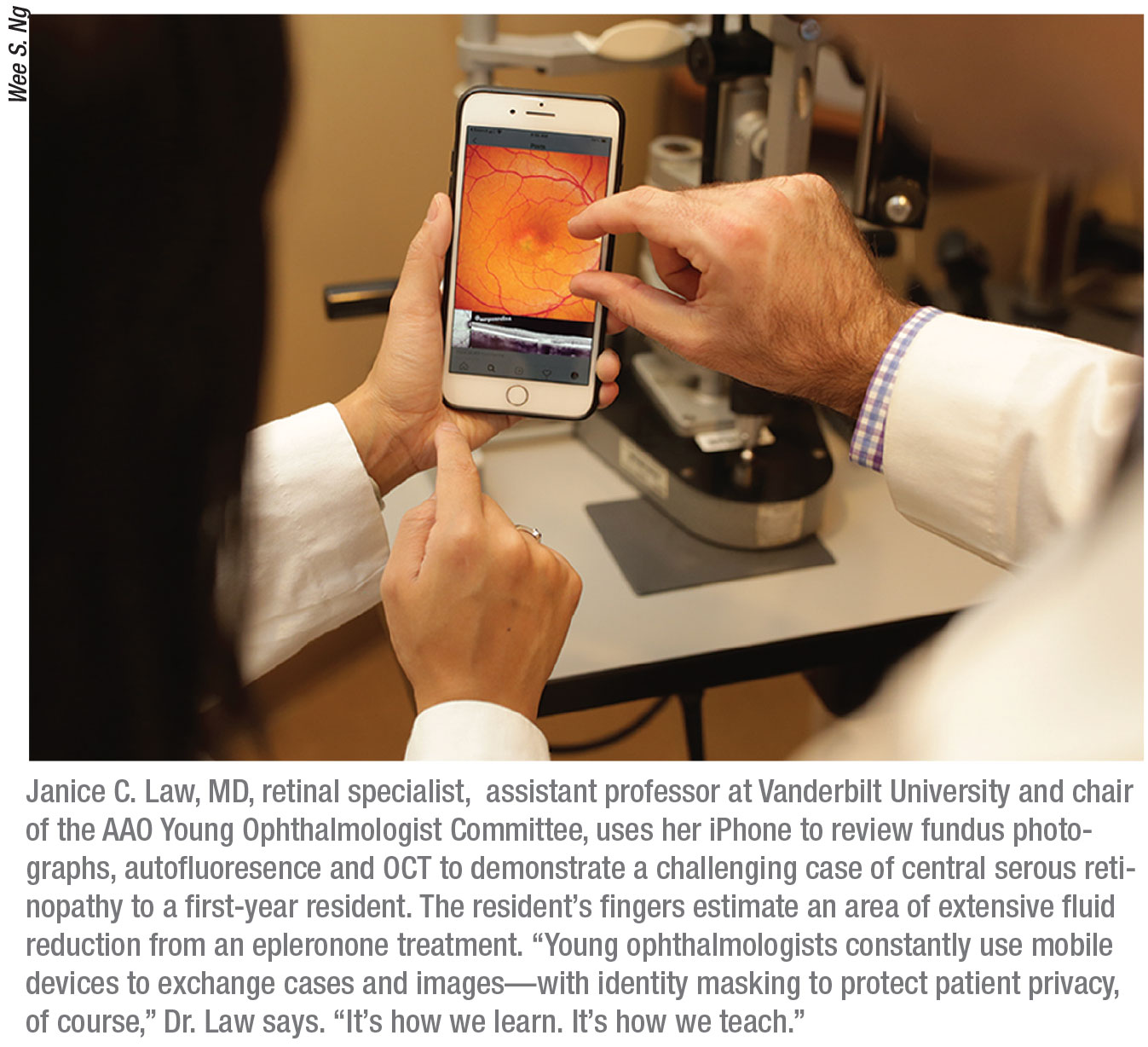

Dr. Law also sees great potential for senior and millennial ophthalmologists to work together. “Young ophthalmologists are looking for mentors and people to share cases openly with—without judgment—so they can learn,” she says. “Senior ophthalmologists can mentor us on coding/billing/practice management—which we may be able to enhance with our technical know-how—and they can mentor us on clinical cases and decision-making.

Senior ophthalmologists would be very good at mentoring young ophthalmologists when it comes to advocacy and leadership in the profession and practice, she adds.

“YOs, in turn, could help bring the practice ‘up to date’ with more efficient use of technology, assisting in clinic flow and improving the patient experience, especially by using apps,” continues Dr. Law. “Web marketing and social media promotion would benefit the practice and can certainly be a notable contribution that the YO can make. We can also spearhead the selection and implementation of an electronic medical records system for the practice.”

“Here’s an example,” Dr. Law says. “I recently went to a doctor’s appointment. I checked in online (like a hotel) paid my outstanding $11 bill via an app (like my bank app), made a follow-up appointment (as I do with my hairdresser), and got a text reminder so I could put the follow-up appointment in my calendar (like a secretary/assistant). All of that was easy. Millennials can make sure that it works this way for the practices in which they work.”

Both Sides Now

Like any other generational differences, many of the ones that separate these two groups may never go away.

“I think that senior ophthalmologists should expect younger ophthalmologists to push back. I mean that is just going to happen,” says Dr. Law. “Young ophthalmologists are committed to medicine but not in the same way as senior ophthalmologists. They don’t have their doctor identities turned on every night or on the weekends.”

But in the long run, say the thought leaders interviewed for this article, these differences will strengthen the profession. “The millennials have different goals than us at times,” acknowledges Dr. George Williams, who counts eight millennials among the 27 doctors at his multispecialty practice. “When it comes to maternity leave, flexibility in scheduling and other work/home balance issues, they very well may be the ones who are right. I have confidence in their ability to do the things that I have to do: be good doctors and take great care of their people. That is what we all do.” REVIEW

1. Pavarini PA, Schaff MF. New barbarians at the gate? What private equity wants from medical practices and how to advise clients. Presentation given at American Health Lawyers Association Physicians and Hospitals Law Institute, Orlando, Florida, 1–3 February 2017.

2. Casalino LP, Saiani R, Bhidya S, Khullar D, O’Donnell E. Private equity acquisition of physician practices. Ann Intern Med 2019 Jan;170:2:114-115.