Ophthalmologists spend much of their time helping patients maintain (or regain) excellent visual acuity. But good binocular vision requires more than just two eyes that see well; the input to both eyes must be successfully combined by our eyes and brain to create our experience of a three-dimensional environment. Sometimes the muscles controlling the eyes have difficulty accomplishing that, leading to double vision. Other times, even when we’re successfully experiencing binocular vision, we pay a price for doing so because maintaining it requires an extraordinary amount of effort.

Here, doctors profile two new systems that can help to diagnose and manage problems tied to maintaining binocular vision.

The Downside of Digital

The digital revolution we’re living through has spawned a host of new devices that invite us to stare at screens. It was probably inevitable that this would lead to vision problems, because when the eye muscles and brain have to maintain a near focus for a long time, we can experience everything from headaches to dry eyes to shoulder and neck pain. Any of these can be misdiagnosed.

EyeBrain Medical, a company located in Costa Mesa, California, has created the Neurolens measurement device and contoured prism glasses to help solve this problem. According to the company, the average American adult spends more than nine hours a day using digital devices—with 70 percent of Americans using two or more devices at the same time. So it shouldn’t be surprising that a huge percent of U.S. adults complain of headaches, neck/shoulder pain and eyestrain when using these devices.

How does stressing of the eyes and brain lead to these symptoms? According to EyeBrain, in addition to combining images in the face of ocular motor imbalances—a challenge in itself—the brain maintains a feedback loop with the extraocular muscles to keep the eyes aligned. The proprioceptive signals involved in that feedback loop are transmitted through the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. When the visual system has to strain to compensate for misalignment and/or disagreement between central and peripheral images, double vision may result; but even if double vision doesn’t occur, the trigeminal nerve can still become overstimulated, leading to trigeminal dysphoria and triggering symptoms. The company claims that this is reflected in complaints reported during more than 17,000 eye exams. That data shows:

• 53 percent of eye-care patients complain of “tired eyes”;

• 50 percent experience neck pain or stiffness;

• 42 percent have discomfort at the computer;

• 42 percent are light sensitive;

• 37 percent have dry-eye symptoms;

• 36 percent complain of headaches; and

• 18 percent experience dizziness.

Fifty-six percent of patients present with at least three of these symptoms.

Addressing the Problem

To help patients deal with this, two things are necessary: First, a device must be able to measure the extent of the problem in a given individual. That’s the purpose of the Neurolens measurement device. Second, a visual aid—in this case, the Neurolens glasses—must be customized to minimize or eliminate that person’s specific problem.

|

| Numerous seemingly unrelated physical symptoms may be related to eye alignment strain. The Neurolens measuring device evaluates the patient’s eye alignment at distance and near and prescribes specially designed lenses to compensate for both. |

Vance Thompson, MD, founder of Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and a professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine, became interested in this in the early 2000s. He explains how the Neurolens device and glasses came about. “We always think about clarity of vision, but not the discomfort caused by poor eye alignment,” he notes. “Ten years ago I had two patients, one post-LASIK and one post-cataract surgery, who felt so dry they were ready to scratch their eyeballs out. However, they had no signs of dry eye and no dry-eye therapy helped. Then, an optometrist colleague, Dr. Jeff Krall from Mitchell, South Dakota, who understood the disparity between central and peripheral vision, put a contoured prism in their glasses and their pain went away. The patients came back saying that their symptoms were gone when they wore the glasses.

“Dr. Krall then told me about A.E. Turville,” he continues. “Dr. Turville described this phenomenon in the 1950s and developed the Turville Ophthalmometer for measuring the imbalance between central and peripheral binocular vision. Although his premise was right on the money, his device was clunky. So, we set out to develop a modern, automated device that could accomplish the same thing, measuring the discrepancy at both distance and near. That was the genesis of the Neurolens system. We also noted that the need for prism is greater up close than at distance, so we patented an idea of Dr. Krall’s: contoured prisms that have more power when the patient is reading at near. The prism gradually decreases as the patient shifts from working at close range to viewing at distance. Those glasses are now sold as Neurolenses.”

How the System Works

According to the company, Neurolenses are the only prescription lenses that use a contoured prism. Measurement of the degree of misalignment at both distance and near is accomplished with the Neurolens eye-tracking device. Patients focus on a single point while a dynamic display of rotating planets and stars allow the device to evaluate peripheral and central vision, providing a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s eye alignment and synchronization, accurate to one-hundredth of a diopter of prism. The results become the basis for the Neurolens prescription.

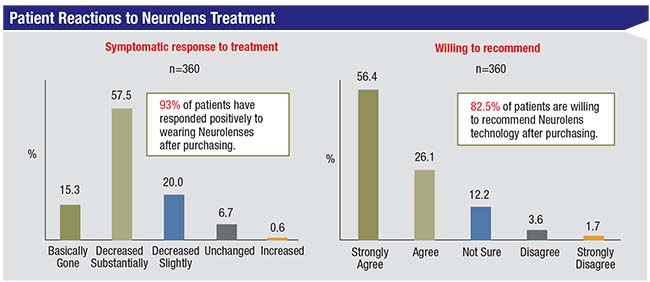

The company says the process of treating the patient involves five steps. First, a Lifestyle Index questionnaire is administered to determine whether a patient is a potential candidate for the glasses. Second, if the patient is a candidate, he undergoes a three-minute Neurolens measurement test to measure any misalignment problem at distance and near. Third, the doctor reviews the results with the patient, explaining trigeminal dysphoria and how it can lead to the symptoms the patient noted on the questionnaire. Fourth, appropriate lenses are ordered online through the company’s ordering portal. Finally, after wearing the glasses for a few weeks, the patient is surveyed to make sure he or she has gotten relief. According to a survey conducted by the company 45 days after treatment, of 360 patients who received the Neurolens glasses, 90 percent experienced symptom relief.1

“Today, I consider this potential problem during every LASIK and cataract evaluation,” says Dr. Thompson. “If the patient has dry eye, eyestrain symptoms or headaches that are out of line with the exam findings, this often explains it. For example, a surgeon came to me for cataract surgery; he noted that he couldn’t do surgery for more than 10 minutes without getting headaches. We measured him and put him in contoured prism glasses, and he went right back to doing 10-hour cases.

“The headaches caused by this problem are hard to treat because the doctors treating these patients don’t realize that a binocular visual issue is part of the problem,” he adds. “This was well demonstrated when we took 160 of our local neurologist’s toughest headache patients—people whose headaches truly made them miserable. We measured all of them for this vision problem and found that many of them did, in fact, have it. Those patients had a 90-percent favorable response to the contoured prism glasses.”

Using It in Practice

David C. Moline, OD, FAAO, a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry who’s been in practice for more than 35 years, bought the first commercially available Neurolens measurement device just over a year ago, and has purchased another since then. (His practice is known for being an early adopter of new technologies.) “We’ve had a very good experience with the device and the Neurolens glasses,” he says. “What’s fascinating is that this company has identified a subset of the population who have significant symptomatology relating to the overuse of digital devices, and this technology really does help them.”

|

Dr. Moline explains that all of his patients are given the questionnaire. “It asks whether the patient has headaches; stiff shoulders; difficulty working at the computer; tired eyes; and/or dry eyes,” he says. “We score patients from one to five. Anybody who has three or more of the symptoms is then tested with the measurement device to see what his eye misalignment is. The test takes three or four minutes to conduct, and it produces a printout with the amount of misalignment and a recommendation for the prescription. We’ve been able to incorporate this into our pretesting routine, so when our technicians look at the survey and see that a patient has three or more symptoms, they automatically run the test before the doctor sees the patient. It gives us a good idea of the potential cause of their symptoms.

“I’d say that about 60 percent of our patients qualify to do the test,” he continues. “Of that group, about 20 percent are good candidates for the special lenses. So about 10 to 12 percent of our patients suffer these symptoms without understanding that misalignment is part of the problem. Those patients are helped significantly by these lenses.”

Dr. Moline says that patient responses range from instant relief to a gradual realization that the symptoms are gone after a month of adjusting to the contoured prism. “In some cases, you put these lenses on the patient and get an immediate, positive reaction,” he says. “Of course, that’s not always the case. Some patients put the lenses on and struggle for two to four weeks. They may experience dizziness or other symptoms as they get used to the contoured prism. Managing patients like this isn’t always easy; they sometimes need a lot of hand-holding. The company recently released a video of a skeptical patient who didn’t believe the glasses would help; in addition, she had a lot of difficulty adjusting to them. But after adjusting to them she forgot to wear them one day and her symptoms returned. Now she’s a believer.”

Dr. Moline says he tried them himself, even though he doesn’t have any of the symptoms listed in the questionnaire. “It took me a while to get accustomed to them,” he notes. “The lenses are progressives—which the company refers to as ‘contoured’—but when I tried switching back to my standard progressives with no prism, I discovered I wasn’t seeing as sharply or feeling as comfortable. I put the Neurolenses on and my vision cleared up immediately. So even though I didn’t have any of the symptoms people complain about, the lenses still improved my vision.”

Practical Benefits

Dr. Moline notes that the glasses are not inexpensive, but they do solve the problem for most patients and the glasses come with a money-back guarantee. “That’s how confident the company is that the lenses will help,” he says. “In fact, patients seldom ask for their money back. During the company’s three-year beta-testing period, about 10,000 glasses were sold. Of those 10,000 people, 85 percent said they’d recommend them to family and friends because of the reduction of symptoms. Furthermore, before I got involved with the product I spoke to a doctor who was part of the beta testing who had sold 1,000 pairs of lenses. He said they’d given two refunds. So I tell my patients, if you buy the lenses and your symptoms get a lot better, you’ll be happy. If you buy them and it doesn’t seem to help, there’s a 100-percent money-back policy.” (Dr. Moline adds that he doesn’t charge patients for conducting the test.)

Dr. Moline notes that all of this leads to another positive aspect of offering this technology: It’s not covered by insurance. “This is a significant potential source of income,” he points out. “The out-of-pocket for the patient can be as high as $850 for the Neurolens glasses, but again, that comes with a money-back guarantee, and if patients get relief, they’re happy they spent the money. Meanwhile, you only need to treat a handful of patients per month to cover the cost of payments on a five-year lease of the device. So it’s a source of revenue that’s new and different, and in our experience very valuable.” (The company declined to specify the cost to the doctor to purchase or lease the measurement device.)

Dr. Moline says the small company behind the system is constantly working to improve the technology. “Once in a while the measuring device has difficulty getting the readings, although for us that’s only been the case in maybe one percent of the patients we test,” he says. “They’re also trying to improve how this concept is presented to the patient, so the patient understands what’s going on. A month ago, for example, we received new marketing materials to help us explain to both staff and patients exactly what the system is doing.”

| ||

| The EyeSwift system uses eyetracking to evaluate the vision of a child (or adult) while the subject watches an entertaining video. (See illustration, below.) |

A Lot of Potential

Dr. Moline notes that being able to measure and treat this problem is something that was not previously available to doctors. “The Neurolens measurement gives us information that’s different from what we’ve had for the past 30 years,” he says. “It uses peripheral vision fusion cues that give a more real-life, accurate measurement than older measuring devices. Of course, we’ve had prism compensation for misalignment for years, but we never had a progressive lens that provides different compensation for distance and up-close in the same lens. That’s new, and it’s one of the biggest things about this product.

“As I mentioned, about 10 to 12 percent of patients benefit from this, and for a few of them, it changes their lives,” he concludes. “They’ve suffered from these symptoms for a long time, with no one knowing why or how to fix it. It’s exciting to have the chance to help them.” For more information about the Neurolens system, visit neurolenses.com/eye-care/.

Vision Assessment in Children

NovaSight, a small startup company in Israel, has created a novel vision-assessment system called Eyeswift, ideal for screening children for vision impairments ranging from poor visual acuity to strabismus. The company states that the Eyeswift system is designed to address children’s unique needs and attention spans; it can detect multiple vision impairments in less than a minute.

The Eyeswift system comprises a pair of occludable LCD glasses that can be worn over prescription spectacles, and a computer (either tablet or desktop). The wirelessly controlled glasses, which can fully occlude either eye digitally on command, and a 90 Hz eye-tracking system, monitor and record eye movements while the child watches an animated video. The system is designed to test visual acuity; visual resolution; stereo acuity; Worth’s four dot test; eye motility; reading skill level; color vision; and contrast sensitivity. In addition, it can detect the presence of manifest or latent strabismus and vergence amplitude, important for detecting convergence insufficiency. After analysis, it provides a detailed report about the child’s vision.

Tamara Wygnanski-Jaffe, MD, head of the pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus unit at the Goldschleger Eye Institute at the Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer, Israel, has been using the system since August 2017. “The first version I used was a prototype,” she explains. “The current version has software and hardware that are much easier to use; the test is shorter and easier to perform, and it’s easier and more fun for the young children who take the test.”

Assessing Strabismus

“Although it’s designed to assess many different visual parameters, I’ve worked primarily with the strabismus part of the system, both in clinical trials and in the clinic, detecting and measuring tropia and phoria,” Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe says. “That’s its most unique function. To do the strabismus test, the subject sits about 50 cm from the screen wearing the occluding glasses. The child fixates on a target, which quickly becomes a very entertaining animated movie, complete with audio. Then the device monitors the subject’s eye usage to determine whether he or she has strabismus, and whether it’s a tropia or a phoria.”

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe explains that the first part of the test determines whether you have strabismus by occluding one eye and tracking the movement of the other eye to find out whether you have no deviation; a right- or left-eye deviation; or an alternating deviation. “The second part of the test determines what type of deviation you have and how big it is,” she says. “In fact, that’s one of the advantages of the Eyeswift system; it can also quantify the amount of strabismus.

“To accomplish this, it does what we would do in orthoptics: the alternate-cover test,” she explains. “Here, it’s done automatically by the computer; each eye is occluded for three seconds, five times, for a total of 30 seconds. Then the software calculates the gaze position of the eye and shifts the target to where the deviation will be larger, and it repeats this process for each eye until there’s no eye movement. This allows the software to calculate the direction of the strabismus, its amplitude and the exact deviation. The strabismus test takes about 49 seconds, although in some cases it may take up to a minute.”

Asked about some of the other tests the Eyeswift can do, Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe says that it checks reading skill level by asking the subject to read an age-appropriate paragraph while monitoring the eye movements. “The system monitors how many fixations and regressions you have, your reading speed, and how long you spent reading each word,” she explains. “This is a good test to do along with the strabismus test, because kids with strabismus or amblyopia sometimes don’t read as well as normal children. With both test results you might, for example, show the parents that the child has strabismus, and that’s why he reads slowly. Or, the child has no strabismus but he’s a poor reader, so you can suggest that the parents work with an educator to help improve his reading skills.”

|

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe notes that the system can also test spatial resolution for young children, similar to what’s called preferential looking, such as Teller acuity. “Small, pre-verbal kids can be shown a butterfly composed of stripes, to see if they follow the butterfly,” she explains. “And when testing visual acuity, there’s a feature where you just touch the computer tablet when you see the letter E or the number. You don’t even have to be verbal to take that test. All of the tests are quick and repeatable, so this system can be used for both screening and diagnosis, and also for monitoring, if you see the patient at different times. You can have all of the data put up on a graph to see the condition improving or worsening over time. That can also be helpful for showing you the effect of surgery or glasses.”

Fast and Easy

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe says the biggest advantage of the Eyeswift system is that it’s very easy for the patient. “It’s interesting, it’s quick and it’s repeatable,” she notes. “Lots of kids like doing it, and it can also be used on adults. Another advantage is that it’s very easy to operate—much easier than operating your smartphone! The software does everything automatically. A technician with very little experience and minimal training can run the tests. Then you can have someone else assess the results, or send them to a reading center, so you don’t need a specialized team at your location.”

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe points out that this is far easier and less expensive than the old methods for diagnosing strabismus. “For example, the cover test has been considered the gold-standard strabismus test,” she says. “To do that test you need an orthoptist, optometrist or pediatric ophthalmologist. That test is great, but it’s manual and time-consuming, and the equipment isn’t universally available. It’s very dependent on the examiner’s skills, experience and level of attention, because if you want to see very small movements, you have to be very observant to detect them. There’s also the expense of having someone qualified to conduct that test, and the problem of inter-examiner variability. These are not issues with the Eyeswift.”

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe notes that other products have been developed by other companies in recent years with the same goal in mind. “Some of them had really good correlations with the gold-standard alternate cover test,” she notes. “However, the equipment often doesn’t fit young children, because you have to restrain the head and fit it into a machine where the subject can’t move freely. Also, many of those devices require a fairly lengthy period of calibration that can strain the subject’s head and neck. Some won’t work if the subject wears glasses, and some of them can’t differentiate between phoria and tropia, so you don’t know if it’s a manifest strabismus or a latent strabismus, which affects how you treat it. This system avoids all of these problems.”

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe notes that the Eyeswift system was originally designed using adult subjects. “Partly for that reason, the Eyeswift is suitable for adults, and it’s even easier to use with adults than with kids,” she says. “Then, when the designers shifted to the pediatric population, it forced them to make the system work faster and more easily, and made them improve the animated movies. Now it can be used even on children less than three years old.”

Asked about the system’s limitations, Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe notes that it uses eye-tracking technology, so it depends on the presence of good ocular motility. “If the patient has a palsy, or the eyes don’t move at all, this system can’t be used,” she says. “However, that’s also true with the standard cover test. Second, you need to have at least 20/200 vision in each eye because you need to fixate on a target. You can make the animation larger or smaller according to the subject’s visual acuity, but the subject has to be able to fixate. Also, the cornea must be clear. The eye tracker uses infrared illumination reflected between the cornea and the pupil to determine the gaze position of the eye; if the cornea isn’t clear, you won’t get that reflection.”

Looking to the Future

Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe notes that some useful tests have not been incorporated into the Eyeswift system yet. “The software doesn’t include a test for distance deviation or the nine positions of gaze, but that will be included in the future,” she says. “Also, this system was not designed to measure torsion, which is relatively rare. Upcoming versions will add these and other tests.”

The Eyeswift system is currently CE-approved. Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe says it should become available in Europe early this year, and is awaiting FDA approval in the United States. This price in the United States is expected to be in the ballpark of $6,000. REVIEW

Dr. Thompson is a founder of EyeBrain Medical and holds stock in the company. Dr. Moline sells the Neurolens to patients but has no other financial ties to EyeBrain Medical or the product. Dr. Wygnanski-Jaffe has no financial ties to NovaSight or the Eyeswift system.

1. Data on file, EyeBrain Medical.