Innovation has always been a part of cataract surgery, with new technology supplanting the old by virtue of its increased speed, safety or both. The procedure is now extremely safe and quick, but could it be improved even further? Three laser companies hope that it can, and are working hard to automate certain aspects of it by way of new femtosecond devices. Our October 2009 article, "The Femtosecond Enters New Territory," took a look at the femtosecond system of LenSx, which had recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the creation of the anterior capsulotomy prior to cataract extraction. This article will explore two other femtosecond lasers in the pipeline from the companies LensAR and OptiMedica.

LensAR

The LensAR laser has been used for just over 250 cataract cases (150 in the

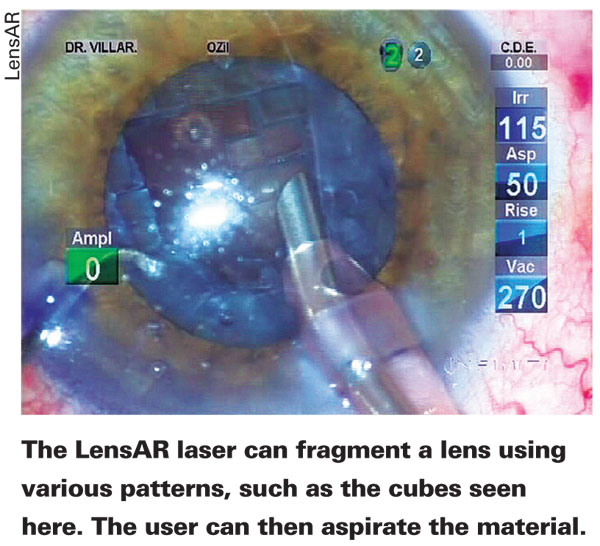

"We've moved on to concentrating on lens fragmentation," says

The challenge now is developing the most efficient way to break up nuclei. "Determining the proper patterns is where we are now," says Dr. Nichamin. "Half of it is tweaking the technology, and the other half is the brainpower and creativity involved with developing new algorithms. We're taking what we know from manual surgery and using it as a starting point, using conventional nuclear disassembly techniques like phaco chop and asking the laser to do what we usually do with manual instruments. We do know that the laser can cut dense lenses without damaging the capsule." He says there's also potential for creating a variety of corneal incisions that are more complex and precise than those currently used, such as incisions with reverse bevels, different types of relaxing incisions and penetrating wounds. "We know we can make limbal relaxing incisions, and are currently developing protocols for a formal study of them," explains Dr. Nichamin. The surgeons are also looking at the possibility of creating intrastromal incisions that have a refractive effect.

Since the prototype machine is in a separate room from the phaco device, using it for certain steps of the procedure adds some time to the process at the moment, as the patient needs to be moved to the operating room to complete the surgery. Dr. Nichamin says, however, that the commercial version of the machine could be in the operating room next to the conventional equipment, and would have less of an impact on the length of the procedure.

Currently, LensAR has submitted its data on capsulorhexis creation to the FDA and it's under review. "If and when 510k approval occurs," says Dr. Nichamin, "we'll establish some machines in the

OptiMedica

OptiMedica also has a femtosecond laser in development for use in various phases of cataract surgery, and is currently treating patients in the

After the device makes the cataract wound and a capsulotomy of a specific shape (either oval or circular), the surgeon can use the device to soften the nucleus. Bascom Palmer professor William Culbertson, MD, has performed surgery with the device as head of Optimedica's advisory board. "We actually use a pattern of 0.5-mm cubes to soften the lens," he explains. "But the surgeon can make other patterns as well, such as circular or spiral patterns. With some lenses, we can aspirate out the lens material without having to use phaco power after it's been pre-softened. With harder lenses, such as those we encounter in the

At this point, however, despite the precision and possible safety advantages, the OptiMedica laser faces a situation similar to the other laser cataract devices in that it looks like it will add time to the procedure. "We envision this being done outside the OR," says Dr. Culbertson. "The laser part of the procedure is done and then the patient moves into the operating room where the procedure is completed and the IOL placed under sterile conditions.

"Though it will make the OR part of the procedure shorter, it will take more time to position the patient under the laser, dock it to the eye, perform the laser and then move the patient," adds Dr. Culbertson. "It's an intermediate stage. It's similar to what happened with the IntraLase. Prior to the IntraLase, LASIK was done under the excimer. But when the IntraLase came along, you had to position the patient under the IntraLase to make a flap and then move the patient to the excimer for treatment."

The Cost Question

Though the femtosecond lasers can make precise capsulorhexes and are honing their ability to soften the cataract, some surgeons wonder if these sophisticated machines will be able to find a place in their practices, given how successful cataract surgeons are with current technology in an atmosphere of declining reimbursements. Will surgeons want to pay both for the equipment and a "click fee" to use it for cataract surgery?

"The technology is robust, and I believe it will change what we do, but the real question is 'How do we pay for it?'" says Dr. Nichamin. "At this point, barring a tremendous change in the government's payment scheme, we're going to most likely introduce this technology through the premium approach. This would mean we'd be charging patients for the use of the laser for those components of the cataract procedure that aren't already covered, such as LRIs.

"There's always a bit of reluctance to give up what we've been using and what we thought had been working well enough, as well as questions about how we'll pay for this more expensive technology," continues Dr. Nichamin. "Ultimately, we figure it out, but at this juncture that's really where the question marks exist. I'm quite confident that, just as we went from PRK to LASIK or extracap to phaco, we'll overcome this challenge as well."