New Approach

Photrexa Viscous and Photrexa are photoenhancers indicated for use in corneal collagen cross-linking with the KXL System.

“This is a brand-new approach and a brand new surgical platform that really represents an advance in the treatment of keratoconus,” says Peter Hersh, MD, medical monitor for the FDA trial and in private practice in Teaneck, N.J.

Michael Raizman, MD, who is in private practice and on the faculty at Tufts Medical School in Boston, agrees. “This is important for keratoconus patients in the United States,” he says. “We have been waiting for this approval for years. Patients in this country have been able to get these treatments through clinical trials, and some doctors have acquired devices and are performing treatments without FDA approval; however, most doctors and patients may feel most comfortable when they are using an FDA-approved drug and device. Because there is no other treatment to prevent the progression of keratoconus, cross-linking has already revolutionized the treatment of keratoconus around the world. It has been available in Europe for more than 15 years and for many years in most other countries. The United States has just been very slow to reach this point.”

Treating Keratoconus

Keratoconus is the most common corneal dystrophy in the United States, affecting approximately 170,000 Americans. It causes the cornea to bulge, creating an abnormal curvature that changes the cornea’s optics, producing blurred and distorted vision that is difficult to correct with glasses. This progressive thinning and weakening can result in significant visual loss and may lead to the need for a corneal transplant.

|

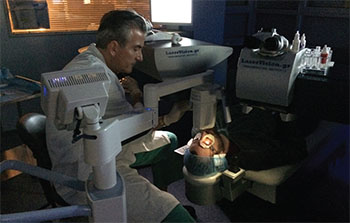

Figure 1. The KXL system. |

“With the approval of cross-linking, most patients will no longer require corneal transplantation,” Dr. Raizman says. “Cross-linking prevents the progression of the disease in nearly all patients who undergo the treatment. One treatment is enough for nearly every patient. It is a very safe, comfortable treatment, so the postoperative recovery is quite manageable with minimal discomfort for all patients including children.”

As a one-time treatment, it is much less expensive than a corneal transplant, which may need to be repeated. “Many of these patients are quite young when they have their first transplant, so they will need multiple transplants, multiple doctor visits after each transplant, and usually eye drops forever,” Dr. Raizman says. “If you add up the total cost, it is probably on the order of forty- or fiftyfold less expensive to treat with cross-linking,” Dr. Raizman adds.

The FDA approval was based on Avedro’s NDA submission, which included data from two prospective, randomized, parallel-group, open-label, placebo-controlled, 12-month trials conducted in the United States to determine the safety and effectiveness of Photrexa Viscous and Photrexa when used for performing corneal cross-linking in eyes with progressive keratoconus.1 Study 1 included 58 patients with progressive keratoconus, and Study 2 included 147 patients with progressive keratoconus. In each study, one eye of each patient was designated as the study eye and was randomized to receive either cross-linking or sham.

The cross-linked eyes demonstrated increasing improvement from month three through month 12 in Kmax, which is defined as the maximum corneal curvature. Progressive keratoconus patients had an average Kmax reduction of 1.4 D in Study 1 and 1.7 D in Study 2 at month 12 in the cross-linked eyes and an average Kmax increase of 0.5 D in study 1 and 0.6 D in study 2 at month 12 in untreated eyes. The difference between the cross-linked and untreated groups in the mean change from baseline Kmax was -1.9 (-3.4, -0.3) D in Study 1 and -2.3 (-3.5, -1.0) D in Study 2.

In clinical studies, the most common ocular adverse reactions observed in treated eyes were corneal opacity (haze); punctate keratitis; corneal striae; corneal epithelium defect; eye pain; reduced visual acuity; and blurred vision.

“The FDA approval of Avedro is a gigantic leap forward for ophthalmologists in the United States,” says A. John Kanellopoulos, MD, who is in private practice in Athens, Greece and in New York City. “It is well-known through the global experience that corneal cross-linking has become the standard of care for stabilizing keratoconus and corneal ectasia. I am personally very excited that this treatment will be available to everyone who is in need in the United States, and I am also excited about the body of clinical work and clinical research that relates to this treatment that is being produced by U.S. clinicians and has been missing all these years in the ophthalmic literature and at ophthalmic meetings.”

How It Works

According the Dr. Kanellopoulos, cross-linking entails removing the corneal epithelium, using either an epithelial brush, diluted alcohol or manual scraping. “Some clinicians tend to prefer an excimer laser scrape of the epithelium,” he says. “In my opinion, this would also add a significant topography-guided normalization in these irregular corneas because the epithelium tends to be irregular. So, a standard PTK of 50 µm would shave off part of the central cone and improve the cornea normality to a degree to have the patient gain anywhere from one to five lines of vision.”

After the epithelium is removed, the cornea is soaked with riboflavin drops placed over a 30-minute period. “Then, the KXL device is placed over the patient’s eye, which is usually held open with a lid speculum,” he says. “We anesthetize with topical anesthesia, usually one drop of proparacaine or Alcaine replenished every 10 to 15 minutes, depending on the patient’s tolerance. The device has a timer with an LCD screen to help the clinician evaluate the progress of the procedure. The surgeon and the staff reinforce patient compliance by letting the patient know how many minutes are left in the treatment. Following the procedure, some clinicians patch the eye, and some use a bandage contact lens. Antibiotic medications and corticosteroids are typically used for one to four weeks, and eyes are typically protected from UV light for two months.”

Although corneal cross-linking has been found to be a safe procedure, complications such as infectious keratitis can occur. “If the device is placed too close to the cornea, there may be a higher amount of energy delivered, which can scar the cornea,” Dr. Kanellopoulos says. “Also, an immune ring has been described after the procedure that may relate to the bandage contact lens use or an immune reaction of the cornea to the procedure; it usually resolves with topical corticosteroids. Cornea melt resembling central toxic keratopathy has been described as well, although all of these are extremely rare complications.”

According to Dr. Hersh, “Cross-linking is much like putting extra wires on a suspension bridge to make the bridge stronger,” and it is very effective. He and a colleague recently reviewed the outcomes of corneal collagen cross-linking for keratoconus or ectasia in a cornea subspecialty practice.2 The study included 104 eyes (66 had keratoconus and 38 had ectasia). The investigators reviewed the outcomes and the natural course of changes in postoperative parameters including Kmax, uncorrected visual acuity and best-corrected visual acuity over 12 months.

At one year, an average of 1.7 D of flattening in Kmax was observed. Mean best-corrected visual acuity improved slightly more than one line (from 0.35 ±0.24 to 0.23 ±0.21 logMAR). All postoperative parameters worsened between baseline and one month and improved thereafter. The study found that eyes with a preoperative Kmax of 55 D or steeper were 5.4 times more likely to gain 2 D or more of Kmax flattening at one year after cross-linking. Additionally, eyes with a preoperative best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or worse were 5.9 times more likely to gain two or more Snellen lines at one year after cross-linking.

This study demonstrates that corneal collagen cross-linking can effectively decrease the progression of keratoconus, with improvements in optical measures in many patients. “Generally, the trend observed was immediate worsening between baseline and one month, resolution at approximately three months and improvement thereafter,” the authors wrote. “In predicting outcomes after cross-linking, no patient characteristics showed correlations with negative treatment outcomes such as loss of vision or continual topographic steepening. However, steeper Kmax (≥55 D) and poorer best-corrected visual acuity (≤20/40) at the time of treatment correlated with better postoperative Kmax and best-corrected visual acuity outcomes at one year, respectively. These outcome predictors should be considered when offering cross-linking to patients with keratoconus or postoperative corneal ectasia.”2

As mentioned earlier, a one-time treatment for stabilizing keratoconus is especially beneficial in children, and cross-linking has also been found to be effective in this patient population.3 A recent study conducted in Switzerland included 33 eyes in 25 patients who were 18 years or younger. Follow-up visits occurred after each of the first four years. Progression was defined as an increase in Kmax of at least 1 D in one year.

Prior to the cross-linking procedure, patients’ mean Kmax was 55.3 ±7.3 D, which decreased significantly after one year to 53.4 ±7.4 D. Progression was stopped in 23 patients, and five cases of presumed progression were identified. One case had significant steepening in Kmax four years after cross-linking, but the topographic parameters were unchanged. Repeat tomography showed that the Kmax was stable. Two cases with limbal vernal keratoconjunctivitis worsened in both corneal tomography and topography.

After resolution of the limbal inflammation, the Kmax values returned to their pre-inflammation values. Additionally, there were two cases of true progression, both of which had advanced keratoconus prior to cross-linking (preoperative Kmax of 64.4 and 75.1 D, respectively).

The Future

According to Rajesh Rajpal, MD, who is in private practice in the Washington, DC, area and is also chief medical officer for Avedro, cross-linking is currently being studied outside the United States as a refractive procedure (photorefractive intrastromal corneal cross-linking [PiXL]). “This uses the Mosaic System by Avedro and different formulations of riboflavin, he says. “It is a customizable cross-linking treatment for low levels of myopia that is being studied transepithelially as well as with removing the epithelium.”

Patients who are good candidates for this procedure are in the relatively low myopia range (0.75 to 2 D). These are patients who don’t typically opt for a refractive procedure because they consider LASIK and PRK as too invasive. “This procedure has had good results transepithelially,” Dr. Rajpal says. “Depending on how trials outside the United States continue to go, and so far they have been very positive, the company would then plan to work with the FDA to have the Mosaic device and those formulations of riboflavin start clinical trials in the United States. Mosaic already has a CE mark in Europe.”

All four doctors interviewed for this article have a financial interest in Avedro. REVIEW

1. Data provided by Avedro Inc.

2. Chang CY, Hersh PS. Corneal collagen cross-linking: A review of 1-year outcomes. Eye Contact Lens 2014;40(6):345-352.

3. Schuerch K, Tappeiner C, Frueh BE. Analysis of pseudoprogression after corneal cross-linking in children with progressive keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol 2016 April (Epub ahead of print).