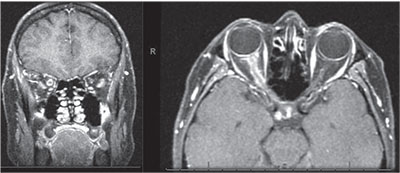

The differential diagnosis for the patient’s pain with eye movements, enlarged blind spot and disc edema in her right eye was broad and included inflammatory (demyelinating optic neuritis, optic perineuritis, optic neuropathy related to systemic rheumatologic disease, idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome), infectious (tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme, Bartonella) and infiltrative/neoplastic conditions (lymphoma, meningioma, glioma, metastatic disease). An MRI scan with and without contrast was ordered for further evaluation; it demonstrated enlargement and circumferential enhancement of the right optic nerve sheath. This was described radiographically as a positive “donut sign” and “tram-track” enhancement (Figures 2 and 3). There was subtle streaking of the retrobulbar fat. The radiographic differential diagnosis included optic nerve sheath meningioma, acute optic neuritis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma and idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome. A CT scan of the orbits was subsequently performed to evaluate for calcifications in the optic nerve sheath that would suggest an optic nerve sheath meningioma, but none were found.

Serologic studies were also ordered, including basic metabolic panel, complete blood count, liver function studies, ACE, ANA, ANCA panel, Lyme antibody, RPR and FTA-antibody, and tuberculosis quantiferon gold test. A chest X-ray showed no lymphadenopathy. All of the above serologic studies returned normal except for the Lyme disease antibody panel, which was positive for Lyme IgM and negative for IgG, consistent with acute Lyme disease. A lumbar puncture revealed a normal opening pressure, cell count, protein and glucose levels, but was positive for CSF Lyme IgM. It was at this point that the patient recalled an odd, target-shaped rash four to six weeks earlier which had seemed unimportant to her at the time because it was self-limited.

With these radiologic and serologic results known, the patient was diagnosed with right optic perineuritis secondary to Lyme disease. She was admitted to the infectious disease service and started on IV ceftriaxone 2 g daily. She was also started on a course of oral corticosteroids with 60 mg of prednisone daily. Her pain with eye movement and visual blur improved rapidly with this regimen. Follow-up examination in the neuro-ophthalmology clinic two weeks after discharge also showed improvement of her disc edema. Two

|

| Figures 2 and 3. T1-weighted post-contrast MRI shows circumferential enhancement of the optic nerve sheath along the length of the optic nerve in the right orbit with sparing of the nerve itself, creating a donut sign on coronal sections (left) and a tram-track sign on axial sections (right). |

Discussion

Distinguishing optic perineuritis from demyelinating optic neuritis is important when selecting diagnostic studies, in therapeutic decision-making and in prognostic associations. Perineuritis may be clinically indistinguishable from typical demyelinating optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial demonstrated that treatment of demyelinating optic neuritis with intravenous corticosteroids hastened short term visual recovery, but long-term recovery wasn’t significantly different from patients who weren’t treated with corticosteroids.1 In contrast, optic nerve perineuritis tends not to be self-limited and requires underlying conditions to be treated with or without supplemental corticosteroid therapy.2 Furthermore, while optic neuritis is associated with multiple sclerosis and may be the first manifestation of this chronic neurologic condition, perineuritis does not have this association. It may, however, be an orbital manifestation of a systemic rheumatologic condition such as systemic lupus or polyangiitis with granulomatosis.2 In patients such as ours, a targeted laboratory workup may help make the diagnosis; it may include ACE, ANA, ANCA panel, Lyme antibodies, syphilis studies and quantiferon gold for tuberculosis. Finally, if the laboratory workup is negative, optic perineuritis can be a manifestation of idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome, as inflammation along the optic nerve is present in 20 percent of cases.3

The clinical distinction between demyelinating optic neuritis and optic perineuritis can be challenging, therefore imaging is necessary to make the diagnosis. As noted above, our patient received an MRI of the brain and orbits with and without IV contrast, which showed enlargement and circumferential enhancement of the optic nerve sheath. The neuroradiologist noted this to represent a positive “donut sign” with “tram-track” enhancement. The donut sign is seen on coronal sections of T1-weighted, post-contrast scans (see Figure 2); the optic nerve sheath enhances peripherally around the optic nerve, while the nerve itself remains dark, giving a donut appearance.4 On axial sections, the nerve is viewed longitudinally; the enhancing sheath is seen as two parallel lines separated by the non-enhancing nerve, which gives the appearance of tram tracks. Tram-track enhancement occurs when neoplastic or inflammatory lesions involve the optic nerve sheath and spare the optic nerve.4 The differential diagnosis for this imaging sign is broad, as many neoplastic and inflammatory conditions can involve the optic nerve sheath. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas are the classic lesion that demonstrates tram-track enhancement.4 However, this patient’s symptoms and acuity of presentation were much more consistent with an inflammatory condition. The diagnosis of optic perineuritis secondary to Lyme disease couldn’t be made until the clinical history, imaging and serologic studies were integrated.

Lyme disease is caused by the spirochete bacterium Borrelia burgdorferia and is the most common vector-borne illness in the United States.5,6 While cases of Lyme disease have been reported in nearly every one of the continental United States, more than 93 percent of them have occurred in the Mid-Atlantic, New England and Great Lakes regions of the country.5 The initial symptoms of Lyme disease include an influenza-like illness, myalgias and the target-like rash of erythema migrans. Of patients who go untreated during this initial stage, up to 15 percent will develop neurologic abnormalities and are diagnosed with neuroborreliosis. Neurologic manifestations are highly variable, including peripheral neuropathies, central nervous system and spinal cord disease and/or ocular involvement. Potential ocular disease is itself diverse, and includes conjunctivitis, episcleritis, perineuritis and chronic uveitis.5 The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends 2 g IV ceftriaxone daily for 14 days (with anywhere from a 10- to 28-day course being acceptable) for the treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis.7 Cefotaxime and penicillin are other potential beta-lactam antibiotic choices, but both must be dosed multiple times per day. Finally, patients intolerant of beta-lactam antibiotics may be treated with oral doxycycline 200 to 400 mg per day in divided doses for 10 to 28 days.7

Optic perineuritis clinically mimics demyelinating optic neuritis, but prompt recognition of this entity is crucial for therapeutic decision-making as well as for potential association with systemic disease. The diagnosis of optic perineuritis most often requires a combination of clinical, imaging, and targeted serologic data. Especially in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions and New England, Lyme disease should be considered as a possible cause of ocular and optic nerve sheath inflammation. REVIEW

1. Beck RW, Cleary PA. Optic neuritis treatment trial. One-year follow-up results. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:6:773-775.

2. Purvin V, Kawasaki A, Jacobson DM. Optic perineuritis: Clinical and radiographic features. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:9:1299-1306.

3. Swamy BN, McCluskey P, Nemet A, et al. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome: Clinical features and treatment outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91:12:1667-1670.

4. Kanamalla US. The optic nerve tram-track sign. Radiology 2003;227:3:718-719.

5. Hildenbrand P, Craven DE, Jones R, Nemeskal P. Lyme neuroborreliosis: Manifestations of a rapidly emerging zoonosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:6:1079-1087.

6. Tilly K, Rosa PA, Stewart PE. Biology of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008;22:2:217-234.

7. Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:9:1089-1134.